Health Reform and the Scope of Benefits for Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Services

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), signed into law in March 2010 (PL 111-148 and see also PL 111-152), mandates that federal agencies, states, businesses, and individuals take steps to expand health insurance coverage in the United States. PPACA is a significant step in increasing access to mental health care for millions of Americans who will gain coverage under reform, including many individuals with moderate or severe disorders.

However, the impact of coverage expansions will depend on how several operational issues are handled by state and federal agencies. One particularly important set of issues is related to the scope of mental health and substance abuse services under expanded health insurance coverage. Individuals with mental or substance use disorders, particularly those with serious and persistent mental illnesses, may require services that are often not covered by the typical insurance plan. Thus particular attention may need to be paid to structuring these new coverage options in a way that meets the health needs of this vulnerable population.

In this article, we examine current public and commercial insurance coverage of services used by individuals with mental illnesses and substance use disorders. We then assess the implications of newly mandated standards for benefit packages offered by public and private plans. We conclude by considering implementation options for addressing some of the challenges in expanding health insurance coverage for vulnerable populations, such as individuals with mental and substance use disorders.

Coverage expansions under PPACA

PPACA expands insurance coverage through a combination of an individual mandate for coverage, penalties for employers who do not cover their workers, broadened eligibility for Medicaid, and subsidies for private insurance coverage obtained through new health benefits exchanges or marketplaces through which individuals and small employers can purchase coverage. PPACA also includes several changes to the regulation of insurance, such as the extension of dependent coverage through age 26, that aim to increase availability and affordability of coverage. The majority of coverage expansions will take place in 2014. Medicaid will then be available to individuals with incomes up to 133% of the federal poverty level (FPL) and will cover an additional 16 million people ( 1 ). Policy makers anticipate that 24 million nonelderly individuals will gain coverage through state health insurance exchanges ( 1 , 2 ). Coverage for the elderly population will remain stable, because Medicare eligibility is unchanged under reform.

Approximately a quarter of currently uninsured adults indicate that they experienced either serious psychological distress or substance abuse or dependence (or both) in the past year; over 6% of uninsured adults show indications of having a serious mental illness ( 3 ). Similarly, more than a quarter of uninsured youths report a past-year major depressive episode, illicit drug use, or both ( 3 ). Thus coverage expansions will include millions of individuals with behavioral health needs, some quite significant. Uninsured individuals with mental illnesses or substance use disorders have relatively low incomes ( 4 ) and are likely to become newly eligible for Medicaid. Actual levels of enrollment in both private coverage and Medicaid will depend on ease of enrollment, outreach and education efforts, insurance costs relative to penalties for noncompliance, and other factors. Even when PPACA is fully implemented, policy makers estimate that approximately 40% of currently uninsured individuals will remain uninsured ( 1 ).

Current coverage of behavioral health services

Individuals with mental illnesses and substance use disorders rely on a range of services to treat or manage their illness. Some of these services overlap with service categories for general medical treatment (such as inpatient hospitalization and pharmacotherapy), but many services (such as partial hospitalization, mobile crisis services, and assertive community treatment) are unique to behavioral health. Further, mental health treatment is sometimes provided by nonmedical providers, such as human service agencies or support groups. People with serious mental disorders may require additional, nonmedical social services, such as income support, vocational training, or housing assistance.

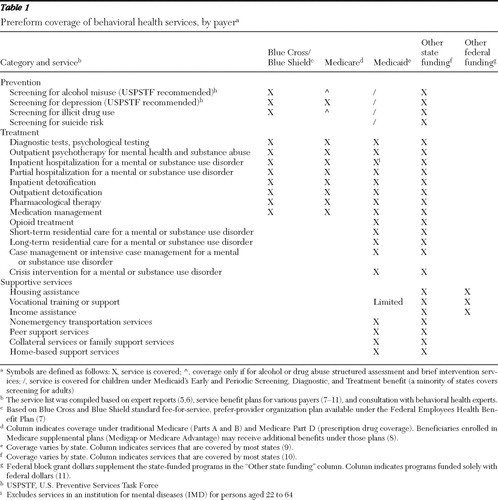

We examined prereform coverage of behavioral health services for five types of payers: employer-based insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, other state programs, and other federal programs. Table 1 , compiled from expert reports ( 5 , 6 ), service benefit plans for various payers ( 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ), and consultation with behavioral health experts, shows how coverage of behavioral health services varies across these payers. Using the standard Blue Cross/Blue Shield plan available through the Federal Employees Health Benefit Plan as a proxy for a typical employer plan, the table indicates that private insurance covers services that fall within the traditional medical model for general medical care, such as outpatient care, inpatient care, pharmaceuticals, and diagnosis and screening. Many behavioral health services, particularly those needed by individuals with serious illnesses, fall outside this scope and are not covered by private insurance. Similarly, Medicare, which was initially modeled after private-sector insurance, covers a limited scope of behavioral health benefits.

|

Behavioral health services are not a specifically defined category of benefits in federal Medicaid law, and although some services used for behavioral health care are mandated by the federal government, coverage of many services is at state discretion. As a result, Medicaid coverage varies across states. However, Table 1 shows that state Medicaid programs typically cover a broader range of behavioral health services than Medicare or private insurance. In addition to general medical services, most states cover long-term services, residential care, intensive case management, and some support services. There are some notable limitations on Medicaid behavioral health services, such as the exclusion of nursing and hospital services in an institution for mental disease (IMD) for those aged 22 to 64 years ( 12 ). Further, Medicaid generally does not cover social support services, such as supportive employment or housing.

Many uninsured individuals with mental illness who receive treatment do so under non-Medicaid, state-funded services. States finance a broad range of services, many of which fall outside the traditional medical model ( 13 ). States set their own criteria regarding how to deliver these services and who may receive them. Many state-financed services are specifically targeted to individuals with serious illnesses. Services may be limited to individuals without other sources of coverage, or states may provide supplemental benefits to fill in gaps in services covered by other payers. State-financed services are supplemented by the Community Mental Health Services Block Grant (MHBG), the largest federal program dedicated to financing behavioral health services. We have limited information on the specific services provided through MHBG funds because these funds explicitly support existing programs (they do not function as stand-alone funding) ( 14 ). Other federal funds primarily finance support services, such as income and housing assistance for individuals with serious mental illnesses.

Prescription drugs play a central role in the treatment of mental disorders. In 2007 among individuals who were treated for mental illnesses or substance use disorders, 84% received pharmacotherapy ( 15 ). Payers use a variety of approaches to structure prescription drug coverage. Commercial insurers typically use tiered formularies, in which cost sharing varies for drugs within a class to encourage use of lower-cost, often generic medications ( 16 ). Less than 1% of commercial plans use prior authorization requirements (that is, requiring preapproval from the plan before coverage). In contrast, state Medicaid programs, which impose very low or no cost sharing for prescription drugs, are more likely to use utilization management tools. In 2006, a total of 25 states required prior authorization for one or more second-generation antipsychotics ( 17 ). Medicare Part D plans use a combination of cost sharing and utilization management tools to restrict use of psychiatric medications.

Behavioral health benefits under new coverage options

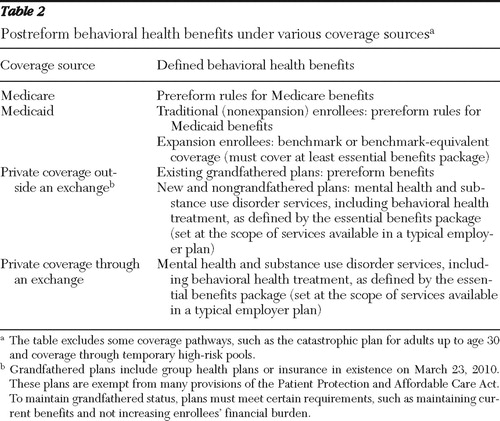

After reform is fully implemented, behavioral health coverage will continue to vary by coverage source ( Table 2 ) because different rules are in place for existing and new coverage sources. PPACA does not substantially change behavioral health services offered under existing coverage (Medicare, Medicaid, and existing private plans that meet specified criteria).

|

For those gaining new coverage under reform, PPACA establishes standards to guarantee access to an "essential benefits package" for individuals covered under "qualified health plans." Included in these standards is the requirement that all qualified plans cover "mental health and substance use disorder services, including behavioral health treatment." The scope of services is to be equal to that covered under a "typical" employer plan. Qualified plans must cover preventive care services recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Prescription drugs are specified as an "essential benefit," but the law does not specify a drug benefit structure—that is, how tiered or incentive-based formularies and utilization management tools may be used by the plans. Furthermore, qualified health plans must comply with the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, which obliges plans providing both general medical and behavioral health benefits to do so with similar financial requirements and treatment limitations.

Although Medicaid coverage remains as is for those meeting current eligibility requirements, individuals moving into Medicaid under new eligibility pathways will receive "benchmark" or "benchmark-equivalent" coverage rather than the full Medicaid benefits outlined in Table 1 . As of 2014, such coverage must contain at least the essential benefits package outlined above. Federal law defines "benchmark" coverage as that equal to the Federal Employees Blue Cross/Blue Shield preferred-provider organization plan, coverage available to state employees, coverage offered by the health maintenance organization with the state's largest commercially enrolled population, or other coverage approved by the U.S Secretary of Health and Human Services. "Benchmark equivalent" coverage includes basic specified services and has an aggregate actuarial value equivalent to one of the benchmark options. PPACA stipulates that if the benchmark equivalent is used, some services (including mental health care and prescription drugs) must be offered at the actuarially equivalent value of the benefit in the benchmark plan. Health reform also specifies that federal mental health parity requirements for group health plans apply to benchmark and benchmark-equivalent plans. States may provide additional services to supplement benchmark coverage, but they are not required to do so.

Implications of scope of behavioral health benefits under PPACA

On the basis of the information in Tables 1 and 2 , it appears that if behavioral health benefits available under qualified health plans are set at those currently available in typical private plans, some services needed by individuals with mental disorders (particularly those required by individuals with more severe illness) will be excluded from coverage. Thus insured individuals who have such disorders will have to rely on other payment sources for some health benefits or go without. This outcome is likely even with implementation of the federal parity law, because several behavioral health services (and providers) have no counterpart general medical service. Examples of such services include nonhospital residential treatment, partial hospitalization, or treatment provided by certified addiction counselors. Federal policy makers are still determining whether the federal parity law requires plans to cover behavioral health services or providers that have no counterpart in medical-surgical services ( 18 ). If not, plans may still impose stringent limits on such services (or not cover them at all). The final interpretation of the parity provision will be a critical determinant of access to some benefits.

Medicaid will play an even larger role in providing insurance coverage for individuals with mental illnesses and substance use disorders post-health reform than it currently does. Most state Medicaid programs already cover mental health services in accordance with at least the essential benefits package, although some states do not meet these criteria for substance use disorder services ( 19 ). Under PPACA requirements, states cannot make Medicaid eligibility more restrictive than under current rules. However, the law does not stipulate that states cannot cut services after reform is implemented. State budgets are facing significant pressure, with Medicaid accounting for a large portion of state spending obligations ( 20 ). Given the likely increase in Medicaid coverage and expenditures, some states may consider cutting behavioral health services as part of a broader effort to trim Medicaid spending. As a comparison of the first and third columns in Table 1 shows, states could significantly cut these benefits and still meet standards for coverage under a typical employer plan.

Furthermore, some newly eligible Medicaid beneficiaries with serious mental disorders may require additional services because the benchmark coverage that will be offered under the expansions is on par with private coverage. PPACA includes some provisions to address this issue. The law specifies that some newly eligible beneficiaries (those exempt from mandatory benchmark coverage under federal law) must have the option of receiving the standard (full) Medicaid package rather than benchmark coverage. Current federal regulations stipulate that this group includes (among others) those who qualify for Medicaid on the basis of being disabled, regardless of whether they are eligible for Supplemental Security Income, as well as those with "special health needs," including children with serious emotional disturbances, individuals with disabling mental disorders, and individuals with mental disabilities that significantly impair their ability to perform one or more activities of daily living ( 21 ). Existing federal regulations do not exempt individuals who meet the definition of a person with a serious mental illness (regardless of whether this illness is disabling), instead leaving to the states the decision to include or exclude this population. Ultimately, access for newly eligible individuals with serious illness will depend on state coverage decisions and final federal regulations on benchmark coverage under PPACA.

A final consideration regarding adequacy of services under reform is whether state-financed supportive services will continue to be available to fill in gaps for individuals with mental health needs. Currently, states finance both treatment services (which may overlap with those covered by other payers) and supportive services (which are generally not covered by private insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid). As a result of coverage expansions, fewer individuals will rely on state-financed treatment services for behavioral health because these services will be covered by other payers; however, it is not clear whether states will expand or contract their coverage of supportive services after reform. On one hand, states may redirect the resources that they currently expend to provide treatment services to expand supportive services. On the other hand, states may use those resources for other expenses, such as their share of the Medicaid match, increased payments to providers, or state expenditures in areas other than behavioral health. In the past, expansions in Medicaid, combined with tight state budgets, led to the latter outcome. That is, states decreased their overall state-only spending on mental health as the availability of matched Medicaid funds increased ( 22 ).

Policy options

Health reform provides an unprecedented opportunity for millions of individuals with behavioral health needs to gain insurance coverage for crucial services, such as psychosocial counseling and prescription drugs, to treat their illnesses. However, for many individuals, particularly those with serious illnesses, the scope of services available under new coverage options will not meet all of their service needs. The challenge of designing benefits to meet behavioral health needs under PPACA rests in recognizing differences in the scope of services covered by different payers; understanding how well each payer's benefits match the needs of those with mild, moderate, or serious illnesses; and steering people to the most appropriate source of coverage for their need.

Policy makers have several options for addressing this challenge. First, regulations can clarify the scope of the essential health benefits package to include services that are important to improving the health of the general population with mental illnesses. For example, essential health benefits could include additional preventive services (for example, screening and counseling for substance use disorders) to help identify those with behavioral health problems. In addition, essential health benefits could include case management for people with chronic diseases, including mental illnesses and substance use disorders, to help those living with lifelong disorders manage their illnesses.

Policy makers also can draw on the experience of Medicare Part D to clarify essential health benefits. Given the importance of prescription drugs to behavioral health treatment, federal guidelines for drug formularies in qualified plans will have important implications for individuals with mental disorders. Medicare formulary guidelines require plans to list "all or substantially all" antidepressants, antipsychotics, and anticonvulsants on their formularies (plans may assign drugs in these classes to high cost-sharing tiers, impose prior authorization or step therapy, or both). This requirement was put in place in part to guard against adverse selection and inhibit plans from limiting coverage for drugs used by people with high total expected drug costs ( 23 ). Experience to date suggests that Medicare formulary guidelines have led to better coverage of psychiatric medications in Medicare than in private plans ( 16 , 24 ).

Second, policy makers can take steps to prevent erosion of Medicaid benefits and ensure that other payment sources (such as state or MHBG funds) finance the services excluded from private or benchmark plans. Policy makers could consider a requirement that states not restrict Medicaid services beyond current levels to correspond to the requirement for eligibility. States could also be required to maintain their non-Medicaid mental health spending at some proportion of their prereform funding. Maintenance of these funding sources will be particularly important for individuals with mental illnesses or substance use disorders who remain uninsured after reform. In addition, these funds will be needed to pay for social support services (such as housing and vocational services) that are not covered by any health payers. These policy actions would require careful consideration of state budgets, which are expected to be both positively and negatively affected by the implementation of PPACA ( 25 ).

Finally, policy makers should consider whether special coverage provisions should be developed for individuals with serious mental illness. In contrast to traditional Medicaid coverage, private or benchmark coverage is not designed to provide the full range of acute and long-term medical and social support services needed by individuals with disabling conditions. Differences in the scope of coverage of behavioral health services across sources of insurance are likely to persist even with the implementation of parity provisions. Rather than stipulating a very broad benefits package for all individuals, policy makers can leverage the scope of services currently available under state Medicaid programs to meet the needs of individuals with serious mental illnesses and substance use disorders. For example, future PPACA regulations could specify that current exemptions to mandatory enrollment in benchmark coverage are continued, allowing individuals with disabling behavioral health problems but incomes above the limit for traditional Medicaid benefits to receive the full range of Medicaid services. Further, the regulations could extend full Medicaid coverage to persons newly eligible for Medicaid who meet the federal definition of serious mental illness. One approach to implementing this strategy is to draw on some screening mechanism to temporarily place individuals with high needs for mental health or substance use disorder services into full Medicaid coverage, with a full determination to follow.

Conclusions

To facilitate access to needed services, expanded coverage under PPACA must provide a scope of benefits to meet enrollees' needs. If behavioral health benefits are defined as services currently available in typical private plans or benchmark coverage, some individuals with mental illnesses or substance use disorders who are insured through private coverage, Medicare, or Medicaid expansions are still likely to face gaps in covered services. It is important to note that many people with mental health needs who will gain coverage under PPACA have serious disorders and rely on the full range of behavioral health benefits to meet their needs. Policy makers will need to develop strategies to ensure adequate coverage of behavioral health services, maintain existing funding sources for wrap-around care, and steer individuals who need the full continuum of behavioral health benefits into more generous coverage options.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors received financial support for this work from Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., and the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Additional support was received under grant R34-MH082682 from the National Institute of Mental Health, grant KL2-RR024154-04 from the National Center for Research Resources at the National Institutes of Health, and grant U48DP001918 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Cost Estimate for the Amendment in the Nature of a Substitute for HR 4872, Incorporating a Proposed Manager's Amendment Made Public on March 20, 2010. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, 2010. Available at www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/113xx/doc11379/AmendReconProp.pdf Google Scholar

2. McGuire TG, Sinaiko AD: Regulating a health insurance exchange: implications for individuals with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 61:1074–1080, 2010Google Scholar

3. 2008 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (online analysis). Rockville, Md. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Available at www.icpsr.umich.edu/cgi-bin/SDA/SAMHDA/hsda?samhda+26701-0001 Google Scholar

4. Kessler RC, Heeringa S, Lakoma MD, et al: Individual and societal effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. American Journal of Psychiatry 165:703–711, 2008Google Scholar

5. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

6. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

7. Blue Cross Blue Shield Federal Employee Program: 2010 Service Benefit Plan Brochure. Available at www.fepblue.org/benefitplans/2010-sbp/bcbs-2010-RI71-005.pdf Google Scholar

8. Medicare and Your Mental Health Benefits. Baltimore, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2009. Available at www.medicare.gov/publications/pubs/pdf/10184.pdf Google Scholar

9. State Profiles of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services in Medicaid. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005. Available at store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//NMH05-0202/NMH05-0202.pdf Google Scholar

10. Funding and Characteristics of State Mental Health Agencies, 2007. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009. Available at store.samhsa.gov/shin/content//SMA09-4424/SMA09-4424.pdf Google Scholar

11. Major Federal Programs Supporting and Financing Mental Health Care. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, Jan 2003. Available at mentalhealthcommission.gov/reports/Fedprograms_031003.doc Google Scholar

12. Buck JA: Recent changes in Medicaid policy and their possible effects on mental health services. Psychiatric Services 60:1504–1509, 2009Google Scholar

13. Buck JA: Medicaid, health care financing trends, and the future of state-based public mental health services. Psychiatric Services 54:969–975, 2003Google Scholar

14. How State Mental Health Agencies Use the Community Mental Health Services Block Grant to Improve Care and Transform Systems. Report prepared for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Alexandria, Va, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute, Dec 2007Google Scholar

15. Garfield R: Mental Health Financing: A Primer. Washington, DC, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, in pressGoogle Scholar

16. Hodgkin D, Horgan CM, Garnick DW, et al: Management of access to branded psychotropic medications in private health plans. Clinical Therapeutics 29:371–380, 2007Google Scholar

17. Polinski JM, Wang PS, Fischer MA: Medicaid's prior authorization program and access to atypical antipsychotic medications. Health Affairs 26:750–760, 2007Google Scholar

18. Interim Final Rules Under the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. Federal Register 75:5416–5417, 2010Google Scholar

19. State Profiles of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services in Medicaid. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005. Available at mentalhealth.samhsa.gov/Publications/allpubs/State_Med/2Appendix.pdf Google Scholar

20. The Fiscal Survey of States. Washington, DC, National Association of State Budget Officers, June 2010. Available at www.nasbo.org/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=gxz234BlUbo%3d&tabid=65 Google Scholar

21. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services: 42 CFR Part 440, Medicaid Program; State Flexibility for Medicaid Benefit Packages (Final Rule). Federal Register 75:23068–23104, 2010Google Scholar

22. Frank RG, Glied S: Changes in mental health financing since 1971: implications for policymakers and patients. Health Affairs 25:601–613, 2006Google Scholar

23. Donohue JM: Mental health in the Medicare Part D drug benefit: a new regulatory model? Health Affairs 25:707–719, 2006Google Scholar

24. Donohue JM, Huskamp HA, Zuvekas S: Dual-eligibles with mental disorders and Medicare Part D: how are they faring? Health Affairs 28:746–759, 2009Google Scholar

25. Health Reform Issues: Key Issues About State Financing and Medicaid. Menlo Park, Calif, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010. Available at www.kff.org/healthreform/8005.cfm Google Scholar