Regulating a Health Insurance Exchange: Implications for Individuals With Mental Illness

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), passed in March 2010, will create new state-based health insurance markets, referred to as "exchanges," which consolidate and regulate the market for individual and small-group health insurance. A well-designed exchange has the potential to increase enrollment in health insurance plans, expand choice, and contain costs through competition. Federal and state policy makers' choices about design of the new market will have important consequences for persons with mental illness.

Individual health insurance markets have historically come up short in providing coverage for treatment of mental illness; state and federal regulation has been needed to secure improvements in coverage over the past 30 years. Recently, improved diagnostic assessment, availability of low-cost treatments, and advances in managed care have ameliorated the "moral hazard" problem of insurance in mental health care ( 1 ). However, other features of the exchanges—open enrollment, individual choice, and imperfect risk adjusters—imply that "adverse selection," the second long-standing problem for insurance markets for mental health care, must be given careful consideration in policy decisions about choice and pricing.

This article considers options for structuring choice and pricing of health insurance in an exchange from the perspective of efficiently and fairly serving persons with mental illness. Health insurance should protect consumers against financial risk, be priced fairly for the sick and the healthy, and encourage efficient health care. By pricing fairly, we mean that lower-income groups should be subsidized and persons with worse health status should not pay more for coverage than healthy persons. Our main concern in this article is how problems related to adverse selection will be handled in an exchange. After an empirical assessment of the underlying driver of selection incentives, the higher overall costs of persons with mental illness, we review relevant experience from health insurance markets that are similar in design to the new exchanges, focusing on adverse selection. Next we discuss options for contending with selection incentives within an exchange. These options tend to limit consumer choice, raising the key regulatory tradeoff: are consumers better served by limiting choice to prevent a "race to the bottom" in effective coverage, or is consumer choice an essential element to promote efficiency among competing plans? We also discuss the problem of choice from the standpoint of consumer awareness of alternatives and the ability of consumers to make good choices from among the large number of alternatives that could be contained in an exchange.

Mental health and health care use among likely exchange participants

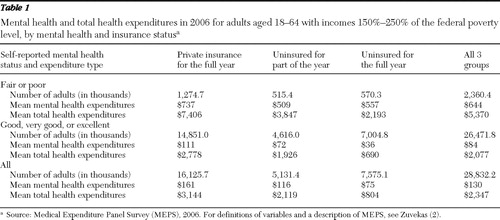

Among persons likely to participate in an exchange, the frequency of mental health care use and the relation to overall health care costs per person are fundamental to assessing the functioning of insurance markets for persons with mental illness. To illustrate the issues, we consider adults aged 18–64 with family income between 150% and 250% of the federal poverty level (FPL). Table 1 contains data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) for individuals who were either privately insured during 2006 or were uninsured all or part of the year. Figures are weighted to national estimates. (Zuvekas [2] has provided definitions of the variables in the table and a description of MEPS.) About 28.8 million people are represented in the categories reported in the table. Individuals with full-year coverage through Medicare or Medicaid are excluded. The groups are further divided by a single indicator of mental health status: self-rated mental health status. We group the five possible mental health status responses into two categories; fair-poor and excellent-very good-good. Overall, slightly less than 10% of the population is in the fair-poor category.

|

For persons in all three insurance categories, spending on mental health care during a year is much higher for persons with fair or poor mental health status compared with those with good, very good, or excellent status. Among the privately insured, for example, average mental health spending per person is $737 for less mentally healthy persons, compared with $111 for the group with better mental health. More relevant for incentives to health insurance plans is another result: total health spending is much higher for persons with worse self-rated mental health. In the privately insured group, average total spending per person is $7,406 compared with $2,778 for those with better mental health. Only $626 of the additional $4,628 spent each year by those with worse self-rated mental health is accounted for by mental health costs directly; the vast majority of the higher total costs is for other health care costs. Although health plans must accept all applicants, the MEPS data imply that plans will have strong incentives to offer low-quality mental health care and make access difficult ( 3 ).

Experience in Massachusetts and other insurance markets

The new exchanges will be operational as of January 1, 2014, and the Congressional Budget Office estimates that by 2019, a total of 24 million people will be insured through an exchange ( 4 ). Several key design features of the exchanges are undefined by the PPACA; for example, an exchange could be run by the state, outsourced to a private authority, or left by default to the federal government to operate ( 5 ). The exchanges are loosely based on the Massachusetts Connector (described below) and will offer plans that cover a defined minimum benefit package, which will include parity for mental health care and provide premium and cost-sharing subsidies for individuals and families in households earning up to 400% FPL. Exchange plans will be more generous than those historically offered in the individual market. For example, in 2000 only 63% of individual health insurance plans offered coverage for inpatient mental health care, and only 48% provided an outpatient benefit ( 6 ).

Previous experience in other markets for private health insurance identifies challenges for the new exchanges.

Massachusetts Connector

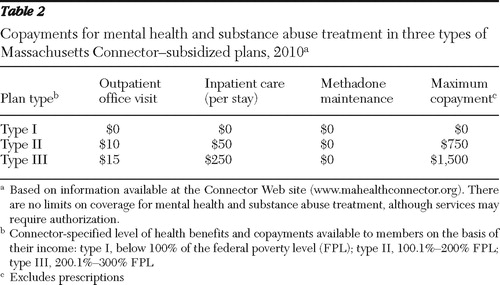

The Massachusetts Connector, a state agency established in 2006, operates an exchange that as of March 2010 had enrolled 177,000 individuals in a health plan ( 7 ). Eighty-six percent of enrollees are in subsidized plans operated directly by the Connector and open to uninsured adults who are U.S. citizens or U.S. nationals and to families earning less than 300% of FPL. All subsidized plans must meet the "minimum creditable coverage" standards determined and regulated by the Connector Authority and offer comprehensive mental health and substance abuse coverage ( 8 ). Cost-sharing requirements in the subsidized plans are determined by household income ( Table 2 ). The plans differ across provider networks and additional offered services (such as reimbursement for fitness memberships or telephone hotline services). As of 2010 the majority of subsidized plans carve out behavioral health services, and the Connector risk-adjusts plan payments using a calculation based on D×CG methodology that incorporates age and gender, as well as prior health claims of the enrollees for whom the Connector has this information ( 9 ).

|

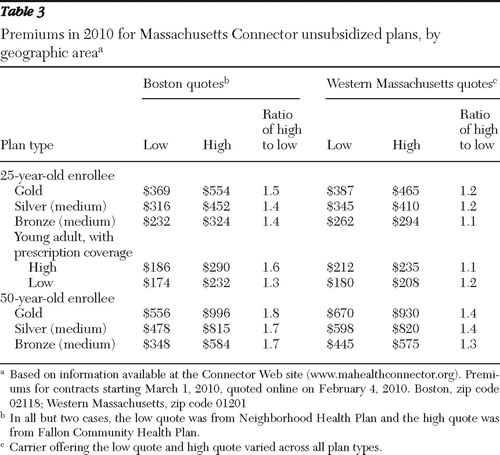

In the unsubsidized portion of the market, the Connector is more passive, supporting the development and offering of health insurance coverage to individuals who do not have another source of coverage and who do not qualify for a Connector-subsidized plan. The Connector operates administrative services, including a Web-based enrollment function, enrollment support, and customer service, and transfers the premiums collected from individuals through to plans on a monthly basis. In 2010 seven insurance carriers participate in the unsubsidized program. Carriers offer plan products categorized into tiers based on actuarial value of coverage (called gold, silver, bronze, and young adult); all plans offer comprehensive mental health coverage. Strategies to minimize adverse selection in the unsubsidized plans were implemented primarily through the health reform legislation, which restricts carriers to use of information on age, residence location, family size, industry, wellness program use, and tobacco use when determining premiums and requires carriers to merge the small-group and nongroup markets ( 10 ). Over the past three years, the benefits offered by plans within coverage tiers have been increasingly standardized ( 8 ). Nevertheless, premiums charged for plans in the same coverage tier and with very similar cost-sharing requirements differ by a factor of up to 1.6 to 1 for a 25-year-old and up to 1.8 to 1 for a 50-year-old in the Boston area, although somewhat less in western Massachusetts ( Table 3 ). It is unclear whether selection or other factors are responsible for the wide range of premiums in the same market for apparently very similar products.

|

In fiscal year 2009 the Connector's reported administrative expenses of $29 million represented 3.5% of total Connector expenses, with the remaining 96.5% paid out to subsidized plans in the form of capitation payments ( 11 ). To figure total administrative costs of health insurance in the Connector, health plan expenses would need to be added to those paid by the Connector itself.

There is little available information about the experience in the Connector of people with behavioral health disorders. According to interviews we conducted with several senior staff at the Connector, the population with mental illness in these plans is higher functioning than that covered through the state's Medicaid program, and persons with mental illness in the Connector faced no special difficulty in making enrollment decisions. Connector community outreach efforts are geographically based and target specific cultural groups; no special efforts are based on disease or health status. The staff at the Connector reported few complaints from the mental health advocacy community about difficulties with enrollment.

Copayment obligations under Connector plans are potentially unlimited, and early evidence indicates that financial risk may be a serious problem for people with chronic illnesses ( 12 ). Mulvaney-Day and colleagues recently surveyed 66 persons from racial and ethnic minority groups who had received free care from a designated safety-net provider for mental health services before Massachusetts state health reform (Mulvaney-Day N, Alegría M, Nillni A, et al., unpublished manuscript, 2009). In the first year of reform, half were still receiving free care. Of those who switched from free care to a Connector plan, one-third reported difficulties with the transition and cut back on their mental health care, and an additional third reported administrative difficulty with the process of reform. An insurance-based payment system—as opposed to getting "free care" from a safety-net provider—requires patients to keep records of payments and submit forms, an unfamiliar and sometimes challenging task for this population. The generalizability of these findings is limited because the study population was primarily female, low-income, and Spanish speaking.

Federal Employees Health Benefit Program

The Federal Employees Health Benefit Program (FEHBP) has run a regulated health insurance market for federal employees (including retirees) and their families since the 1960s ( 13 ). The FEHBP evolved into the paradigm of "managed competition" proposed by Enthoven in 1980 ( 14 ), wherein enrollees choose plans annually and plans (qualified by the Office of Personnel Management [OPM]) compete on price and benefit offerings. Plans must accept all who seek to enroll. The U.S. government, acting as an employer, pays up to 72% of the average plan premium for each plan in a market (single or family and not above 75% of the plan's premium), and the employee pays the balance. Thus the employee faces the "incremental average cost" of coverage, giving the participating plans imperfect but some incentives to balance decisions about extra coverage and cost against the higher premiums that must be charged (15; Glazer J, McGuire TG, unpublished manuscript, 2009). In 2010 there were several national plans (for example, Aetna and Blue Cross) and more than 200 local plans, largely health maintenance organizations (HMOs).

Parity for coverage of mental health and substance use disorders was successfully implemented in the FEHBP plans in 2001 and evaluated by Goldman and colleagues ( 16 ). Some plans, primarily those with more management of care, covered mental health at parity before the regulation. Among the plans studied in the evaluation, only one "unmanaged" plan experienced greater utilization after parity. Plans tended to introduce more managed care, largely in the form of "carved out" benefits after parity ( 17 ). The FEHBP evaluation confirmed the general finding from earlier research that parity for mental health benefits can be implemented at little net cost in the presence or with the addition of managed care ( 1 ).

The FEHBP's experience of mental health coverage and cost before parity is also relevant. During the early years of the FEHBP, mental health care was covered at parity in national plans ( 18 ), but generous coverage proved unviable with individual choice of coverage ( 19 ). Padgett and colleagues ( 20 ) found that use of mental health care in the Blue Cross "high option" plan was two to three times higher per person despite slight differences in coverage, leaving heavy adverse selection as the only explanation for the large observed differences in costs. Health plans reacted to the threat of enrolling an "adverse selection" of health care risks. Foote and Jones ( 21 ) documented deterioration in coverage throughout the 1980s, in spite of OPM resistance to cutbacks. Regulation of nominal benefits cannot prevent plans from "managing" mental health costs aggressively. In 1980 behavioral health services accounted for 7.8% of total FEHBP claims costs; by 1997 this had fallen to 1.9%. Foote and Jones noted that during this period most employers, with their more limited consumer choice of health plan set-ups, were improving coverage for mental health care, and employer coverage surpassed rather then fell short of what was offered in the FEHBP.

Large employer and Medicaid contracting experience

Many large employers structure an insurance market for their employees—in effect, creating an exchange within the firm. Most "solve" the moral hazard and selection-related problems that arise with mental health care use and are able to expand financial protection through parity-like benefits by offering limited choice among plans managing care ( 1 ). In a first step, employers qualify one, two, or a small number of managed care plans from which employees may choose. These plans might be from a single insurer, eliminating the insurer's incentives to engage in risk selection. As part of this negotiation, the employer contracts with the insurer, paying an individual and family rate that is based on experience. Alternatively, the employer may bear the health insurance risk and contract only for administrative costs from the plans (possibly with some rewards or penalties related to cost and performance targets). State Medicaid programs contract with managed care plans in broadly similar fashion.

For example, employees at Harvard University choose among an HMO and point-of-service (POS) plan offered by the university itself through physicians on salary at the Harvard University Group Health Plan and an HMO, POS, and preferred-provider organization (PPO) plan offered by the independent Harvard Pilgrim Health Care. All choices include unlimited coverage of inpatient and other facility care for mental health and substance use disorders and unlimited outpatient visits subject to copayments. Care is managed in all plans. Harvard decides what premiums employees should pay and subsidizes enrollment for lower-income employees more than for higher-income employees. For example, the employee premium for family coverage at the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care HMO is $229 per month for an employee making less than $70,000 per year and $376 per month for an employee making more than $95,000 per year.

From the standpoint of the average employee or Medicaid recipient, there is some but limited choice. Plans differ in degree of management and coverage for out-of-network care. Provider networks overlap. Although choice is limited, employees and their families face essentially no risk of financial adversity as a result of mental illness.

Pricing an exchange: setting plan payments and enrollee premiums

Premiums paid by enrollees and paid to plans can be judged in terms of their incentives for efficient behavior on the part of plans and enrollees and in terms of fairness. Even the simple two-way cut of the population based on self-rated mental health status ( Table 1 ) reveals very large average total cost differences between those with higher or lower self-assessed mental health status. A health plan makes or loses money according to how premiums are related to average costs in a population. If premiums paid to the plan are roughly age-gender and geographically adjusted average costs (plus a loading fee), plans will have a strong incentive to discourage enrollment of persons with mental illness by skimping on the quality of or ease of access to mental health care.

Risk adjustment of premiums paid to health plans can move premiums toward expected costs, potentially ameliorating plans' incentives to underserve persons with mental illness. However, the power of risk adjustment to align revenues with expected costs is limited by the underlying data and by regulation. Variables available for risk adjustment may poorly predict future health care costs, especially for some chronic illnesses such as certain mental illnesses. For example, in the California Health Insurance Purchasing Cooperative (HIPC) in the 1990s, a voluntary exchange open to small groups, the risk adjustment methodology excluded mental health experience because, in part, coding for these services was thought to be imprecise and coverage at the time was partial ( 22 ). Adverse selection in the California HIPC eliminated the more generous PPO plans from the exchange ( 23 ). Furthermore, in some versions of an exchange, premiums paid by enrollees are paid directly to plans. Risk-adjusting the premiums paid to plans thus also implies charging sicker people more to enroll.

The state-based exchanges created under health reform limit the degree to which plans can differentiate premiums paid by enrollees on the basis of expected cost-related factors, such as age and gender, and by prohibiting use of "preexisting conditions" in rate setting. Exchange authorities, as intermediaries, could play a more direct role in enrollee premiums, just as employers do in the case of employer-provided health insurance, where it is the employer, not the plan, that sets the premium for membership to the worker. For example, all persons could be charged premiums to join plans based only on age, gender, and income, but plans themselves could be paid on the basis of age, gender, and past diagnoses. Level of premiums for health plans is a powerful selection device in a managed competition environment (Glazer J, McGuire TG, unpublished manuscript, 2009), and more direct regulation of premiums should be considered. Intermediation for purposes of fairness and efficiency can be done in the subsidized and unsubsidized parts of an exchange.

Facilitating enrollment in health exchanges

Choice in health plans serves heterogeneity in "taste" for insurance among consumers and allows for static and dynamic competition among the plans. However, incentives for selection and increasing complexity associated with more choice can inhibit effective decision making. Thus the ability of exchange participants to choose plans well and navigate the enrollment and reenrollment process is important to the stability and sustainability of an exchange.

Challenges with enrollment and choice are common in exchanges. Difficulties with paperwork requirements and the enrollment and reenrollment processes have been reported among enrollees in the Massachusetts Connector ( 24 ). In Florida a survey of Medicaid enrollees who were in a demonstration project that required them to select from a set of preapproved health plans found that beneficiaries had low awareness of the program, difficulty understanding health plan information, and difficulty choosing a plan ( 25 ). In this study 11% of the overall Medicaid sample and 43% of the adult sample that received Supplemental Security Income reported a mental health condition; the authors tested for and did not find any difference in these results by health condition. In the Medicare Part D exchange, the elderly choose from among many (often more than 50) private prescription drug plans. Thus far, enrollees in the Part D exchange have not maximized their potential savings in drug spending, because most beneficiaries did not select the lowest-cost plan available to them in the first year of the program ( 26 ). In a randomized experiment, 28% of beneficiaries who received personalized information about Part D plans with lower costs switched from their current plans, compared with 17% of beneficiaries who were simply directed to a Web site where they could learn such information on their own ( 27 ).

Although these studies did not focus on populations with mental illness, this collection of evidence suggests that consumers in an exchange are not well equipped to navigate the enrollment and reenrollment process or to make choices from among a large set of plans on their own. Because of cognitive deficits or incentives related to selection, individuals with mental illness may particularly benefit from having someone in an advisory role to assist them in navigating the exchange.

Brokers often advise small employers about health plan choice. The absence of brokers was an impediment to the success of past state-level HIPCs, which were not effective on their own at marketing products to small groups and whose customers (small groups) reported wanting help from agents in selecting plans and downstream support with issues such as claim disputes ( 23 ). However, brokers are often paid commissions by plans and have their own financial interest in customer choices. Exchange models that do not employ brokers have the potential to lower overall costs because enrollees avoid broker commissions when they purchase plans. This has not been the case in the Massachusetts Connector, where it is required that plans sold through the Connector are sold in the outside market at the same price ( 28 ).

Other parties could assist enrollees in an exchange. Providers in health care settings could help patients complete and submit eligibility and enrollment applications at the point of care. Provider payments for behavioral health from exchange plans must be adequate so that providers are willing to help their patients seek coverage through these plans. Social workers, community organizations, and the mental health advocacy community can also assist people with enrollment in exchange health plans.

An exchange's centralized administrative function can also have an important role in enrollment and plan choice. The exchange could opt to be passive, simply facilitating access to health plans via the Internet and other marketing materials that are also available through other channels. (The analogy here is an Expedia.com for health insurance.) Or an exchange can be more involved with its consumers, providing detailed quality information along with individualized decision and enrollment support. This assistance may be particularly valuable to patients with mental illness who are searching for a health plan that will cover care received from a particular provider. An exchange can selectively contract with and offer a limited number of plans, simplifying the choice process. Finally, structuring the reenrollment process so that the default for enrollees is automatic assignment into their previous plan (and so that switching plans or dropping coverage requires an enrollee to take action) can eliminate time-consuming and challenging reenrollment paperwork and avoid unnecessary gaps in coverage.

Options for structuring choice of plan

Hard experience indicates that a passive exchange that allows free entry of private health insurance plans with discretion to determine benefits (within regulatory constraints), manage care, and set premiums (also constrained by regulation) is unlikely to lead to good insurance outcomes for persons with mental illness. Incentives to underprovide care to this population will be strong, and actions to limit de facto access and benefits will be outside the scope of the exchange authority's control. Discouraging enrollment and encouraging disenrollment—"Someone with your level of need really would be better off elsewhere"—will be difficult to prevent. We do not discuss design of the benefits themselves as part of structuring choice. Federal parity law applies to coverage in the exchanges, although interpretation of parity is not straightforward when services provided for general medical care and mental health care are not equivalent ( 29 ).

Three options for improving insurance outcomes by restricting choice are worthy of consideration. First, carve out all or part of mental health benefits. Carve-outs are part of many state Medicaid and private health insurance plans. Carve-outs limit enrollees' choice of where to turn for mental health care but permit choice of other coverage. The main advantage of carve-outs is that they diminish selection-related incentives to underserve persons in need of mental health care. An exchange authority, by use of a separate contract to the carve-out vendor, is able to directly control the resources going into mental health care and other dimensions of the quality of and access to care. The main disadvantage of a carve-out is the more difficult coordination with general health care providers and potential cost-shifting between the two insurance contracts.

A second option is to provide reinsurance for some mental health care costs (possibly along with some reinsurance for general health care costs). Reinsurance of costs above a certain annual threshold (for example, $2,000) or for certain types of care (such as hospital care after five days per year) can have dramatic effects on the likely gains and losses and therefore on the incentives to enroll and serve persons with mental illnesses. Reinsurance need not be 100% after a threshold but could be set to allow for some risk sharing—for example, the plan would be responsible for 30% of costs after $2,000 and the exchange authority would be responsible for 70%. By contracting with a reinsurer, the authority absolves the basic plans of risk of high-cost mental health care, diluting incentives for selection. The disadvantage of reinsurance is the diluting of plan incentives to manage care effectively, particularly around the reinsurance boundary.

Third, and our preferred option, is to run the exchange in the same way that an employer runs its employee benefits and address selection and cost control (moral hazard) issues by choice of contractor. Employers do not rely on setting elaborate risk adjustment formulas and then allowing their employees to choose from any plan that decides to offer coverage. Employers pursue their health benefit objectives by deciding which plans (a limited number) to contract with. Active selection of plan options, rather than passive manipulation of payments and premiums to influence market outcomes, has been the route chosen by private decision makers to solve the very same problems faced by public decision makers now structuring exchanges ( 30 ). This approach would economize on administrative costs and brokers' fees. Many states contract for health insurance for their employees in ways modeled on those of private employers. In Massachusetts, for example, the widely studied Group Insurance Commission serves this function ( 31 ). This approach models exchanges on the successful sector of the private health insurance market, not on the problematic one.

Conclusions

This article considers how the structure of plan choices and the pricing of health insurance will affect the success with which new health insurance exchanges serve people with mental illness. The role played by the exchange authority will be particularly important. Risk adjustment of plan payments is unlikely to adequately contend with selection incentives to underserve persons with mental illness. The exchange authority may need to use its intermediary position to decouple rules for setting plan payments from rules for setting enrollee premiums. The exchange authority can also assist choices and design the exchange to help consumers make efficient choices. Finally, the exchange authority should consider following the lead of private employers and limiting the number of plans offered to exchange members on the basis of quality (including quality of vulnerable services such as mental health care) and cost. Competition can be maintained as plans contend to be one of the selected products. The limitation of choice would be no worse and mostly better than that experienced by the 60% of the U.S. population covered by employer-based insurance. The main advantage, and what we think thus far outweighs the cost, is the application of a proven strategy for administering broad benefits at good quality for the full range of health care needs, including mental health.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors are grateful to Samuel Zuvekas, Ph.D., Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, for analysis of the MEPS data. Richard G. Frank, Ph.D., and staff at the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and at Mathematica Policy Research provided helpful comments on a draft of the article. The authors alone are responsible for analyses and conclusions.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Barry CL, Frank RG, McGuire TG: The costs of mental health parity: still an impediment? Health Affairs 25:623–634, 2006Google Scholar

2. Zuvekas S: National Estimates of Health Insurance Coverage, Mental Health Utilization, and Spending for Low-Income Individuals, 2009. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Available at www.ahrq.gov/data/meps/lowinc/lowinc.htm Google Scholar

3. Frank RG, McGuire TG: Economics and mental health; in Handbook of Health Economics, Vol 1. Edited by Culyer A, Newhouse JP. Amsterdam, Elsevier, 2000Google Scholar

4. Congressional Budget Office (CBO): Letter to Representative Nancy Pelosi: Estimate of the Reconciliation Act and HR 3590. Washington, DC, US Congress, 2010Google Scholar

5. Kingsdale J: Health insurance exchanges: key link in a better-value chain. New England Journal of Medicine 362:2147–2150, 2010Google Scholar

6. Gabel J, Dhont K, Whitmore H, et al: Individual insurance: how much financial protection does it provide? Health Affairs Web Exclusives W172–181, 2002Google Scholar

7. Connector Summary Report. Meeting materials disseminated at Connector board meeting, Mar 11, 2010. Boston, Commonwealth Health Insurance Connector Authority, 2010. Available at www.mahealthconnector.org Google Scholar

8. Report to the Massachusetts Legislature: Implementation of the Health Care Reform Law, Chapter 58, 2006–2008. Boston, Massachusetts Health Insurance Connector Authority. Available at www.mahealthconnector.org Google Scholar

9. Holland P: Commonwealth Care FY 2011 Procurement Update: Risk Adjustment. Board of Director's Meeting, Jan 14, 2010. Boston, Massachusetts Health Insurance Connector Authority, 2009Google Scholar

10. An Act Providing Access to Affordable, Quality, Accountable Health Care. Chapter 58 of the Acts of 2006. Boston, Massachusetts Legislature. Available at www.mass.gov/legis/laws/seslaw06/sl060058.htm Google Scholar

11. Financial Statements and Required Supplementary Information, June 30, 2009, and 2008. Presented at the Board of Director's meeting, Nov 12, 2009. Boston, Commonwealth Health Insurance Connector Authority, 2009. Available at www.mahealthconnector.org Google Scholar

12. Consumers Experience in Massachusetts: Lessons for National Health Reform. Menlo Park, Calif, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009. Available at www.kff.org/healthreform/7976.cfm Google Scholar

13. Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP). Washington, DC, US Office of Personnel Management. Available at www.opm.gov/insure/health Google Scholar

14. Enthoven AC: Health Plan: The Only Practical Solution to the Soaring Cost of Medical Care. Reading, Mass, Addison-Wesley, 1980Google Scholar

15. Bundorf MK, Royalty A, Baker LC: Health care cost growth among the privately insured. Health Affairs 28:1294–1304, 2009Google Scholar

16. Goldman HH, Frank RG, Burnam MA, et al: Behavioral health insurance parity for federal employees. New England Journal of Medicine 354:1378–1386, 2006Google Scholar

17. Barry CL, Ridgely MS: Mental health and substance abuse insurance parity for federal employees: how did health plans respond? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 27:155–170, 2008Google Scholar

18. Reed L: Coverage and Utilization of Care for Mental Health Conditions Under Health Insurance: Various Studies. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1975Google Scholar

19. McGuire TG: Financing Psychotherapy: Costs, Effects, and Public Policy. Cambridge, Mass, Ballinger, 1981Google Scholar

20. Padgett DK, Patrick C, Burns BJ, et al: The effect of insurance benefit changes on use of child and adolescent outpatient mental health services. Medical Care 31:96–110, 1993Google Scholar

21. Foote SM, Jones SB: Consumer-choice markets: lessons from FEHBP mental health coverage. Health Affairs 18(5):125–130, 1999Google Scholar

22. Shewry S, Hunt S, Ramey J, et al: Risk adjustment: the missing piece of market competition. Health Affairs 15(1):171–181, 1996Google Scholar

23. Wicks EK, Hall MA: Purchasing cooperatives for small employers: performance and prospects. Milbank Quarterly 78:iii,511–546, 2000Google Scholar

24. Community Partners Survey: How Do Outreach Workers View Massachusetts Health Care Reform After Two Years of Implementation? Amherst, Mass, Community Partners, 2008Google Scholar

25. Coughlin TA, Long SK, Triplett T, et al: Florida's Medicaid reform: informed consumer choice? Health Affairs Epub 27:w523–532, 2008Google Scholar

26. Abaluck J, Gruber J: Choice Inconsistencies Among the Elderly: Evidence From Plan Choice in the Medicare Part D Program. NBER working paper 14759. Cambridge, Mass, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2009Google Scholar

27. Kling JR, Mullainathan S, Shafir E, et al: Misperception in Choosing Medicare Drug Plans. Nov 2008. Available at citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.151.8467&rep=rep1&type=pdf Google Scholar

28. Gruber J: Massachusetts health care reform: the view from one year out. Risk Management and Insurance Review 11:51–63, 2008Google Scholar

29. Donohue J, Garfield R, Lave J: The Impact of Expanded Health Insurance Coverage on Individuals With Mental Illnesses and Substance Abuse Disorders. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services. 2010Google Scholar

30. Glazer J, McGuire TG: Private employers don't need formal risk adjustment. Inquiry 38:260–269, 2001Google Scholar

31. Sinaiko AD: Essays on Consumer Behavior in Health Care. Doctoral dissertation. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University, Department of Health Policy, 2009Google Scholar