Community Pharmacist Services for People With Mental Illnesses: Preferences, Satisfaction, and Stigma

Inequalities in health services delivery and utilization for people with mental illness have been demonstrated repeatedly ( 1 ). Poorer outcomes for this population in regard to general health, such as circulatory diseases, mortality from natural causes, and access to interventions (including medications), are well documented ( 2 , 3 , 4 ). Several factors have been identified as contributing to these disparities in health service access and delivery, including stigma ( 5 , 6 ). Stigma associated with mental illness has been described as negative attitudes formed on the basis of prejudice or misinformation that are triggered by markers of illness ( 1 , 5 ). Illness markers include atypical behaviors, noticeable medication-related adverse effects, and the types of medications prescribed ( 5 , 7 ). These markers allow for the perpetuation of stigma concerning people with mental illness, but they also allow community pharmacists to identify patients with a broad range of what are often unaddressed health needs.

There are many accessible community pharmacists, and they have the potential to contribute to improved health outcomes for people with mental illnesses through patient-centered, collaborative, preventive, and treatment services ( 8 , 9 , 10 ). There are a limited number of investigations assessing pharmacists' attitudes toward people with mental illnesses and fewer still focusing on service delivery ( 11 , 12 , 13 ). The patient's perspective regarding community pharmacy services for persons with mental illnesses who are taking psychotropic medications remains to be well characterized.

The purpose of this survey of persons with mental illness and their experience with psychotropics in outpatient clinic settings was to determine experiences with, preferences for, and satisfaction with services provided by community pharmacists and the perceived stigma associated with these professionals.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was developed to address the objectives of the study. The survey was designed to collect information regarding availability of community pharmacy services, consumers' preferences for and satisfaction with those services, and their experiences of stigma and discrimination. Ethics approval was received from the Capital District Health Authority Research Ethics Board in February 2008, and the survey was completed by April 2008.

To assess face and content validity of the survey, a focus group was conducted with four persons with mental illnesses who had experience taking psychotropic medications. Modifications were made to the survey on the basis of focus group feedback. Formats of survey questions were dichotomous, ordinal (Likert scale), ranking, and short answer. For questions in a series of similar format, response set bias was avoided by intermixing negatively and positively worded statements.

The aim was to recruit a sample of 100 people that represented a mix of mental illnesses (including bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, and schizophrenia and related disorders) that could be generalized to similar patients of outpatient mental health clinics who receive psychotropic medications at community pharmacies.

Participants were recruited for the survey while attending appointments at four outpatient mental health clinics. Clinics were located in a tertiary care hospital, an ambulatory care facility, and two community-based mental health facilities in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were at least 19 years of age and were taking at least one medication dispensed at a community pharmacy for the treatment of a diagnosed mental illness. Clinic staff informed patients of the anonymous survey, and those who were interested in participating were given the survey along with brief instructions on how to complete it by one of the on-site researchers. Informed consent was implied when participants completed the survey. To avoid recruitment bias, all patients visiting the mental health clinics were invited to participate in the study while waiting for their appointments. Clinic staff were given the option to exclude anyone whom they considered to be inappropriate for the survey (exclusion criteria included issues of literacy, competency, and illness severity). Participants completed the survey independently, but when questions arose the researcher was available to clarify how to complete the survey without influencing responses. Most surveys were completed on site, but some participants chose to mail in their completed survey using the provided self-addressed, stamped envelope.

Data were entered into SPSS, version 15.0 for Windows. Findings were summarized and reported descriptively with means, standard deviations, proportions, and frequencies. Comparisons were made with chi square analysis and Fisher's exact test for dichotomous variables. Two-sided test probabilities are reported. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to measure the association between two continuous variables.

Results

Eighty-one persons completed surveys (25 were returned by mail), and two patients were excluded because of poor survey comprehension, resulting in 79 surveys for the final analysis. No record was maintained by clinic staff (receptionists) of the number of refusals. As such, response rate was not calculable. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1 .

|

Psychiatrists were ranked highest, as the most commonly used and best resource for information about psychotropic medications. [A table of participants' information resources is available as an online supplement to this brief report at ps.psychiatryonline.org .] Pharmacists were ranked as the second most commonly used and best resource. Family doctors also were ranked second, in a tie with pharmacists, for most commonly used resource, and they were ranked third for best source of psychotropic information. All other resources scored markedly lower.

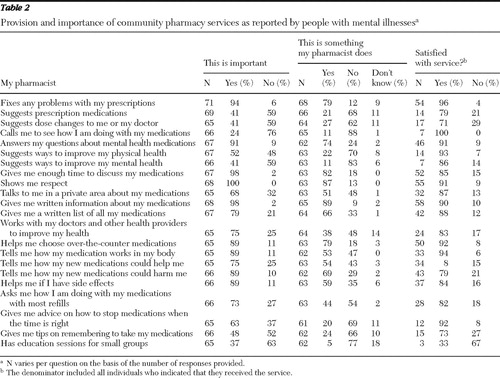

Aspects of care and services identified as important by 90% or more of respondents included being treated with respect, having sufficient time for discussions about medications, receiving written information, fixing prescription problems, and answering questions about psychotropic medications ( Table 2 ). Most respondents were satisfied with the services when they were offered. According to participants, the least important pharmacy services were telephone callback services, educational sessions for small groups, and pharmacist-based suggestions for changes in medications and dosing of medications. However, a strong correlation between the availability of a pharmacy service and its perceived importance was evident across the 22 items assessed. [A figure showing the pattern of these correlations is provided as an online supplement to this brief report at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

|

A few pharmacy services were identified as being important but frequently not available ( Table 2 ). The most notable gaps in these relatively unavailable services included discussing how to stop medications at the appropriate time, collaborating with other health providers, providing information on how the medication works, receiving help with side effects, and talking about medication response when the prescription is refilled.

Fifty-five of 79 (70%) participants reported taking medications for a physical health condition. Thirty-five of 67 (52%) thought that it was important for pharmacists to suggest ways to improve general health, and 14 of 63 (22%) reported that their pharmacist did this for them. Thirty-one of 68 (46%) respondents indicated that they were tobacco smokers, and 13 of 30 (43%) indicated that their pharmacist provided suggestions or advice for quitting. Sixty-three of 69 (91%) indicated that their pharmacists did not ask them about their blood pressure or cholesterol level. When analyzed by age (older than age 42 or age 42 or younger), there were no significant differences in the rate of inquiries about smoking status, blood pressure, or cholesterol.

Seventeen of 74 (23%) reported experiencing some or lots of stigma or discrimination from pharmacists. [A figure showing sources of stigma rated by respondents is provided as an online supplement to this brief report at ps.psychiatryonline.org .] There was no apparent association between stigma and self-reported diagnosis (anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia) or type of psychotropic taken (anxiolytic, antidepressant, mood stabilizer, or antipsychotic). The rate of stigma respondents perceived from pharmacists was similar to rates associated with other health providers and lower than the rates reported from nonmedical professionals. Stigma and discrimination were most often attributed to employers, coworkers, family, and friends.

Sixty-four of 78 (82%) respondents agreed that pharmacists are understanding when it comes to helping people with mental illness, and most respondents disagreed that pharmacists talked down to them (56 of 77, 73%) or were reluctant to serve them (64 of 77, 83%); however, 20 of 76 (26%) indicated that they did not feel comfortable speaking with pharmacists about their mental health medications. [A figure showing patients' perceptions of pharmacy services is provided as an online supplement to this brief report at ps.psychiatryonline.org .] Stigma associated with interactions with pharmacists was significantly more likely to be reported by persons who also reported other negative perceptions and experiences with pharmacists. [A table of perceptions and associated degrees of stigma is provided as an online supplement to this brief report at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

Seventy-one of 76 (93%) respondents indicated that they almost always go to the same pharmacy, with half stating that they preferred to speak with the same pharmacist at each visit. Few (four of 76, 5%) respondents reported changing pharmacies because of bad experiences relating to stigma or discrimination.

Discussion

Our results indicate that consumers of mental health services generally have a positive perception of community pharmacists and their services. The results also suggest that expectations are limited to standard pharmacy services, that gaps in services exist, and that a minority of people experience discomfort or stigma when speaking with community pharmacists.

The traditional role of the community pharmacist includes providing patients with information about medications and resolving prescription issues when dispensing medications. In this survey, the traditional role was recognized as important and frequently provided. Pharmacists were ranked highly as a source of information about medications and were found to be respectful and available. However, clinically oriented services, such as working collaboratively with other health providers, making dosing or treatment recommendations, monitoring response to treatment (by follow-up telephone calls or with refills, for example), and addressing the individual's physical and mental health needs, were found to be relatively unimportant, unavailable, or both. This finding suggests that respondents' expectations of community pharmacists are low and do not match the services that pharmacists can provide ( 8 , 9 ). The services that were not perceived as important correlated with services that respondents did not receive. It is expected that these impressions would change as experience with the variety of services provided increases.

Our respondents frequently noted gaps in services that they perceived as important but not offered. Pharmacists are well trained to educate and support patients regarding psychotropic medication, including discussing how a medication works, monitoring for treatment response and adverse effects at follow-up visits, resolving adverse effects, and guiding patients through the process of stopping treatment. It is not clear why these services are not provided consistently. Lack of specific pharmacist training has been identified by other investigators ( 12 ), but the problem may also be related to a mismatch in pharmacist and patient expectations. Taken together with the reported gap in collaboration with other health providers, our findings suggest that respondents preferred community pharmacists to work more closely with them and their mental health care providers. In recent years there has been significant progress in formalizing collaborative mental health care that welcomes community pharmacist participation ( 8 , 14 ).

Satisfaction was reported by more than seven out of ten respondents for almost all services provided—a factor that has been linked to medication adherence ( 15 ). It is concerning that 76% of respondents indicated that their pharmacist does not provide them with tips on remembering to take their medications because it is well established that people taking medications for chronic conditions, including mental illnesses, demonstrate poor adherence.

Given disparities in general medical outcomes for people with mental illness, especially regarding cardiovascular diseases and related treatment, pharmacists can play a valuable role in offering services for therapeutic assessments and monitoring of general medical conditions and medications ( 8 , 9 ). Results from our sample indicated that few pharmacists provide suggestions in this regard (for example, considering smoking status, blood pressure, and cholesterol level) and infrequently ask people with mental illnesses about their general medical health, regardless of a patient's age, despite the abundance of opportunities. Working collaboratively with other health providers would help enable community pharmacists to determine the medication-related issues (such as when a medication is indicated but not prescribed or prescribed but not taken) of consumers with mental illnesses. The results from our study indicate that patients want this service and could benefit from it.

Although approximately 75% of the sample reported not experiencing stigma or discrimination with their community pharmacist, less than 60% indicated that they were comfortable speaking about their psychotropic medications and related illnesses with pharmacists. A lack of privacy or failure to use an available private counseling room in pharmacies likely contributed to this, but other factors may also be important. The potential for stigma and discrimination in community pharmacies has been demonstrated in several countries ( 11 ), and initiatives to improve exposure of pharmacists to persons with mental illnesses in practice and training have been suggested ( 12 , 13 ). Results of some research indicate that community pharmacists are uncomfortable with discussing mental illnesses and have inadequate training in this area ( 12 ). This is consistent with our findings that some respondents perceived pharmacists as reluctant to serve them or as talking down to them, especially among respondents who reported experiencing stigma at the pharmacy. This may also explain why respondents infrequently used private counseling areas of their pharmacies.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to compare patients' perceived stigma and discrimination in regard to community pharmacists and other health professionals and members of the community. Almost all participants in our sample indicated that they preferred to go to the same pharmacy for their medication and other pharmacy needs, and a significant number indicated that they preferred to interact with the same pharmacist, suggesting that the relationship they have with their pharmacist is important. Another interpretation of this finding is that familiarity with one pharmacy or pharmacist may mitigate potential exposure to further stigma and discrimination if the person received services at a different pharmacy or by a different pharmacist.

Several limitations of our study should be noted. Based on the number of prescriptions, number of pharmacy visits, types of psychotropics used, and self-reported psychiatric diagnoses, our results apply to many but not all people with mental illnesses who are taking psychotropics. Our sample included middle-aged adults primarily with depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia-related disorders. Children were excluded, and very few patients over the age of 65 participated. People with other diagnoses were not well represented (such as those with eating disorders, attention-deficit disorder, or addictions). All recruitment sites were located in an urban center.

To minimize response bias, surveys were completed independently at a mental health clinic or at home. Most participants had little direct contact with the researchers beyond our providing basic instructions on how to complete the survey; those who had direct contact were not informed that the researchers were pharmacists. We do not feel that volunteer or recall biases were likely to have significantly affected the veracity or generalizability of the results.

Difficulties with comprehension of certain aspects of the survey may have affected the validity of some results. For example, responses to the questions of most frequently used and best information resources were highly correlated. Use of operational definitions of "most frequently used" and "best information" could have limited this problem.

Conclusions

Persons with mental illnesses perceived standard services provided by pharmacists as important. Expectations of pharmacists' services were low and were not aligned with the range of services that pharmacists can provide. Pharmacists should assess services they provide to persons with mental illnesses and determine whether expectations and needs are being met and make any necessary improvements. This includes services for general medical health conditions that require pharmacotherapy with routine monitoring and follow-up and closer collaboration with other health providers.

Although stigma was perceived to be similar to that associated with other health providers and less than stigma associated with other community members, this study revealed that one in four persons experienced stigma at community pharmacies. Community pharmacy staff members need to examine and address factors that can predispose, enable, and reinforce activities and behaviors associated with stigma toward people with mental illnesses in their practice settings.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research study was completed as a requirement of Ms. Black's hospital pharmacy residency.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Sartorius N: Stigma and mental health. Lancet 370:810–811, 2007Google Scholar

2. Kisely S, Smith M, Lawrence D, et al: Inequitable access for mentally ill patients to some medically necessary procedures. Canadian Medical Association Journal 176:779–784, 2007Google Scholar

3. Hiroeh U, Kapur N, Webb R, et al: Deaths from natural causes in people with mental illness: a cohort study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 64:275–283, 2008Google Scholar

4. Kisely S, Smith M, Lawrence D, et al: Mortality in individuals who have had psychiatric treatment: population-based study in Nova Scotia. British Journal of Psychiatry 187:552–558, 2005Google Scholar

5. Schulze B: Stigma and mental health professionals: a review of the evidence on an intricate relationship. International Review of Psychiatry 19:137–155, 2007Google Scholar

6. Stuber J, Meyer I, Link B: Stigma, prejudice, discrimination and health. Social Science and Medicine 67:351–357, 2008Google Scholar

7. Schulze B, Angermeyer MC: Subjective experiences of stigma: a focus group study of schizophrenic patients, their relatives and mental health professionals. Social Science and Medicine 56:299–312, 2003Google Scholar

8. Bell JS, Rosen A, Aslani P, et al: Developing the role of pharmacists as members of community mental health teams: perspectives of pharmacists and mental health professionals. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 3:392–409, 2007Google Scholar

9. Bell JS, Whitehead P, Aslani P, et al: Drug-related problems in the community setting: pharmacists' findings and recommendations for people with mental illnesses. Clinical Drug Investigation 26:415–425, 2006Google Scholar

10. Gardner DM: Collaborative mental health care: effective and rewarding. Canadian Pharmacists Journal 140(suppl 1):S11, 2007Google Scholar

11. Bell JS, Aaltonen SE, Bronstein E, et al: Attitudes of pharmacy students toward people with mental disorders, a six country study. Pharmacy World and Science 30:595–599, 2008Google Scholar

12. Phokeo V, Sproule B, Raman-Wilms L: Community pharmacists' attitudes toward and professional interactions with users of psychiatric medication. Psychiatric Services 55:1434–1436, 2004Google Scholar

13. Bell JS, Whitehead P, Aslani P, et al: Design and implementation of an educational partnership between community pharmacists and consumer educators in mental health care. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 70(2):28, 2006Google Scholar

14. Mental Health in a Primary Care Context: Collaboration Is the Key. Mississauga, Ontario, Canadian Collaborative Mental Health Initiative. Available at www.ccmhi.ca Google Scholar

15. Finley PR, Crismon ML, Rush AJ: Evaluating the impact of pharmacists in mental health: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy 23:1634–1644, 2003Google Scholar