Assessment and Treatment of Co-occurring Eating Disorders in Publicly Funded Addiction Treatment Programs

Lifetime prevalence of anorexia nervosa is estimated to be less than 1%, and lifetime prevalence of bulimia nervosa is estimated to be 1%–3%, among American women in the general population ( 1 ). However, prevalence of eating disorders seems to be higher in substance-abusing samples, although differences in sampling and measurements have resulted in a wide range of estimates of co-occurrence. A review of 51 reports on the comorbidity of eating and substance use disorders found a range of co-occurrence from none to 55% (median=17%) ( 2 ). The purging subtypes of bulimia are most commonly associated with co-occurring substance use and eating disorders. Alcohol is the substance most commonly associated with co-occurring disorders ( 3 , 4 ).

The co-occurrence of eating and substance use disorders can result in severe consequences, such as more severe forms of eating disorder behaviors (such as laxative abuse and food restriction) ( 5 ). High severity of alcohol use is related to fatal medical outcomes for women with anorexia ( 6 ). Women with bulimia and substance use disorders have higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity and personality disorders than women with bulimia and without substance use disorders ( 5 , 7 ). Psychiatric conditions that tend to co-occur in this population are depressive and anxiety disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder ( 8 ) and borderline, antisocial, histrionic, obsessive-compulsive, and avoidant personality disorders ( 9 ).

Despite the high prevalence and increased severity of co-occurring eating and substance use disorders, little is known about the availability of treatment resources for these patients. This survey was conducted to increase understanding of current treatment resources available to patients with co-occurring substance use and eating disorders who present for addiction treatment.

Methods

Data for these analyses were derived from the National Treatment Center Study (NTCS), a longitudinal group of surveys of addiction treatment providers in the United States. The analyses focused on a nationally representative sample (N=351) of publicly funded programs. Public centers are defined as those that receive more than 50% of their annual operating revenues from federal, state, or local grant sources. Surveyed programs offer treatment for alcohol and drug problems and provide a level of care at least equivalent to structured outpatient treatment as defined by the American Society of Addiction Medicine patient placement criteria. Data were collected during on-site visits conducted between January 2005 and August 2006. Details on the sampling procedures and inclusion criteria used in the selection of the sample are available in prior publications ( 10 ). Study protocols were reviewed and approved by the University of Georgia's institutional review board. After the study was described to the participating program directors, their written informed consent was obtained.

The on-site interviews with program administrators included a series of questions regarding the extent to which the programs identified and treated patients with eating disorders. Eating disorders were defined as referring to any or all of the DSM-IV diagnostic categories (including bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder). We combined the categories in order to limit the number of queries added to this lengthy interview. Administrators were asked about intake assessments and admission policies for patients with eating disorders. Among programs admitting patients with eating disorders, information was collected on the percentage of patients with eating disorders, whether patients can be admitted solely for eating disorder treatment, and whether the program has access to eating disorder treatment services.

Programs providing on-site services were asked about staff training in treatment of eating disorders and how eating disorder services are delivered. An open-ended question asked the administrator to describe how treatment services for patients with eating disorders differed from the program's standard addiction treatment.

Analyses were conducted with SPSS statistical software and included descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and percentages) to describe the sample. The initial analyses consisted of determining the proportion of programs that did or did not assess or treat eating disorders. All programs were classified as not admitting patients with eating disorders (does not admit), admitting patients with eating disorders but not treating the eating disorder (admits but does not treat), or admitting patients with eating disorders and treating the eating disorder (admits and treats). A Levene test for homogeneity of variances showed no statistically significant differences in these variances for these three groups, despite large differences in group sizes.

These categories were compared on a number of variables selected from the larger set of NTCS items to identify distinguishing characteristics of programs that provide eating disorder services. The selected variables reflect organizational, clinical, and patient characteristics that may be related to eating disorder treatment. For example, use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and use of gabapentin were selected as variables because these medications may be beneficial in treatment of eating disorders. Analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to determine differences among the three treatment categories. Some of the cases had incomplete data and were not available for all analyses, resulting in totals of fewer than 351 cases.

Eating disorder treatment services were also compared by the gender composition of programs. Finally, qualitative analyses identified treatment practices and barriers to eating disorder treatment.

Results

Half of the programs (N=173, or 51%) screen admissions for eating disorders at intake and assessment. These programs were almost evenly divided, with 28% (N=95) screening all patients and 23% (N=78) screening patients only if an eating disorder is suspected. Over one-quarter of the programs (N=49, or 29%) that conduct eating disorder screenings use a standardized diagnostic interview (14% of the total sample). The remaining programs that screen for eating disorders rely on an informal evaluation by a clinical staff member or the clinical history provided by the patient's primary care physician. Approximately 6%±11% of the client population in all programs were reported to have an eating disorder.

Over one-fourth (N=100, or 29%) of programs admit all patients who screen positive for an eating disorder regardless of severity, whereas 48% (N=169) admit patients whose eating disorder is not deemed severe enough to interfere with addiction treatment. Almost all programs require a primary drug or alcohol addiction diagnosis, with less than 7% (N=21) of programs admitting patients solely for eating disorder treatment. Fewer than one in six programs (N=51, or 17%) attempt to treat eating disorders. Only 3% (N=9) have a formal referral arrangement to address eating disorders. The remaining programs do not offer any services to address eating disorders.

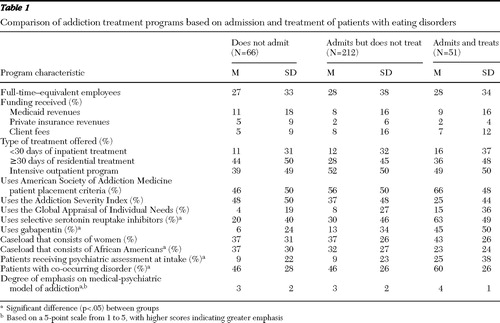

To identify characteristics of programs that treat patients with eating disorders, we categorized the programs into one of three groups: does not admit (N=66), admits but does not treat (N=212), and admits and treats (N=51). Results indicated that the three types of programs are organizationally very similar ( Table 1 ). The primary differences were between admit-and-treat programs and the other programs. Admit-and-treat programs are significantly more likely to address patients' needs from a psychiatric perspective, as seen by their use of medications, such as SSRIs and gabapentin, use of psychiatric assessments, admission of patients with other co-occurring psychiatric disorders, and a higher degree of emphasis on the medical model. Also, admit-and-treat programs had significantly lower caseloads of African-American patients.

|

Four out of five of the programs in this sample treat men and women (N=279, or 81%), whereas 11% (N=37) are women-only programs and 8% (N=28) are men-only programs. When compared with gender-mixed (N=42, or 16%) and men-only programs (N=2, or 8%) by ANOVA, the women-only programs had a higher percentage offering services for eating disorders (N=7, 19%). However, the small number of women-only and men-only programs did not provide adequate power to determine statistical significance (p=.144).

The 51 admit-and-treat programs provided additional information on how they addressed eating disorders. Qualitative data showed three distinct ways in which the treatment of patients with co-occurring eating disorders differs from standard addiction treatment. First, patients with eating disorders tend to receive individual therapy, often with a mental health counselor or licensed clinical social worker trained in treatment of eating disorders. Second, treatment emphasizes food-consumption behaviors, such as the development of a specific meal or nutrition plan, the keeping of food-intake journals, and so on. Third, patients with eating disorders tend to be monitored for bulimic behaviors, such as their activities at mealtime, trips to the bathroom, and so on.

Admit-and-treat programs reported having at least one staff member trained in eating disorder treatment. For about half of these programs (N=24, 47%), this person is a psychiatrist or other physician, whereas 53% (N=27) reported having a counselor trained to treat eating disorders. Only two programs employed a certified eating disorder specialist. In most programs (N=46, or 90%) patients with eating disorders were integrated with other addiction treatment patients. Only five programs (10%) offered a separate track for treatment of eating disorders. All programs used individual counseling to address the eating disorder, 55% (N=28) used group therapy, 57% (N=29) used family therapy, and 47% (N=24) used pharmacotherapy.

Administrators of programs that admit but do not treat patients for eating disorders (N=212) were asked a series of questions to learn more about why eating disorder treatment was not offered. The four most frequent reasons were that no staff were trained in eating disorder treatment, that there was inadequate medical staff or medical resources, that eating disorder treatment requires a more intensive level of care than the program provides, and that there was insufficient demand for these services relative to the resources required.

Discussion

This survey of a nationally representative sample of publicly funded substance abuse treatment programs explored the assessment and treatment of co-occurring substance use and eating disorders, types of eating disorder services provided in addiction treatment programs, and barriers to eating disorder treatment. We found that only half of publicly funded programs reported conducting any screening for co-occurring eating disorders, and only 49 (14%) programs in this sample use a standardized assessment instrument to assess for eating disorders. In general, the programs reported a lower prevalence of patients with co-occurring eating disorders (6%), compared with earlier cited estimates of 17% ( 2 ). However, this percentage is larger than that seen in the general population and warrants assessment for this disorder in addiction treatment.

Given the low rate of assessment and unstandardized assessment techniques for eating disorders, it would not be surprising that programs underestimate their prevalence in treatment populations. However, it also may be the case that these programs do not experience a high case mix of patients with co-occurring eating disorders. Caucasian women are more likely to experience anorexia or bulimia, whereas African-American women are more likely to experience binge-eating disorder, which is not fully recognized in DSM-IV ( 11 ). As such, eating disorders among African Americans may be underdiagnosed. In our sample, admit-and-treat programs were more likely to report a lower percentage of African-American patients than programs that do not provide eating disorder treatment, suggesting that assessment may be more focused on anorexia and bulimia.

Despite the high prevalence of eating disorders among women, we found only insignificant trends for programs to provide eating disorder treatment services in relation to their proportion of female patients or by the female gender composition of the program.

Eating disorder treatment requires a multidisciplinary treatment approach ( 12 ), which may be difficult for addiction treatment programs to provide. Also, patients with co-occurring eating and substance use disorders often have more severe eating disorder symptoms ( 5 , 6 ) as well as other co-occurring axis I and II disorders ( 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 ) that increase the complexity of treatment as well as the resources needed to provide adequate care.

Admit-and-treat programs were more likely to provide psychiatric services and have the resources to provide individual therapy for eating disorders with trained professional staff. Although evidence-based integrated treatment for eating disorders is not yet available, most of the programs attempt to integrate substance use and eating disorder treatment. Admit-and-treat programs were also more likely to use medications such as SSRIs and gabapentin. SSRIs are commonly used to treat co-occurring depression, and gabapentin is used to treat anxiety disorders, and both depression and anxiety are common co-occurring psychiatric disorders that are common in this population.

This survey was limited to publicly funded treatment programs and may not reflect the current assessment and treatment practices of private treatment facilities. The results also were limited by the inability to accurately identify the actual proportion of patients with eating disorders admitted to the programs. It is possible that the populations served by the programs have a low prevalence of eating disorders and do not need additional, costly services for this condition. Alternatively, it is possible that these populations experience a high prevalence of eating disorders that are neither diagnosed nor treated. It is possible that programs did not consider patients with binge-eating disorder or other eating disorder conditions, which may have underrepresented the prevalence of eating disorders in their treatment populations. The results also were limited by the self-report responses of the administrators, who may not have been aware of the practices and skill levels of staff.

Conclusions

Despite the high prevalence of co-occurring substance use and eating disorders, most publicly funded addiction treatment programs do not address eating disorders either through assessment or treatment, possibly because of limited resources and the perception of low need. Primary eating disorders are most often treated in psychiatric facilities with better resources. However, there may be a substantial number of patients with co-occurring eating and substance use disorders admitted to addiction treatment programs. These patients may be better served if addiction treatment programs increase their ability to assess and address eating disorders. Programs that are unable to provide eating disorder treatment may develop referral relationships with appropriate mental health care providers for these services.

These results highlight the need for further research. Use of standardized assessments that include all eating disorders will more accurately identify the prevalence of eating disorders in addiction programs. Studies of private-sector treatment programs may find a larger percentage of patients with co-occurring substance use and eating disorders. Replication of the survey with larger numbers of single-gender programs also may reveal whether female-only addiction treatment programs are more likely than other programs to offer eating disorder services. These results underscore the need for implementing standardized assessments, as well as developing and testing eating disorder interventions among persons with substance use disorders.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The research for this report was sponsored by grants K24-DA-019855, R01-DA-014482, U10-DA-13035, U10-DA-013043, and U10-DA-15831 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors thank Candace Hodgkins, Ph.D., for her thoughtful review of the manuscript.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

2. Holderness CC, Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP: Co-morbidity of eating disorders and substance abuse: review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders 16:1–34, 1994Google Scholar

3. Beary MD, Lacey JH, Merry J: Alcoholism and eating disorders in women of fertile age. British Journal of Addiction 81:685–689, 1986Google Scholar

4. Goldbloom DS, Naranjo CA, Bremner KE: Eating disorders and alcohol abuse in women. British Journal of Addiction 87:913–919, 1992Google Scholar

5. Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Carter FA, et al: Lifetime comorbidity of alcohol dependence in women with bulimia nervosa. Addictive Behaviors 22:437–446, 1997Google Scholar

6. Keel PK, Dorer DJ, Eddy KT, et al: Predictors of mortality in eating disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:179–183, 2003Google Scholar

7. Grilo CM, Levy KN, Becker DF, et al: Eating disorders in female inpatients with versus without substance use disorders. Addictive Behaviors 20:255–260, 1995Google Scholar

8. Johnson JG, Cohen LK, Kasen S, et al: Psychiatric disorders associated with risk for the development of eating disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 70: 1119–1128, 2002Google Scholar

9. Sansone RA, Fine MA, Nunn JL, et al: A comparison of borderline personality symptomatology and self-destructive behavior in women with eating, substance abuse, and both eating and substance abuse disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders 8:219–228, 1994Google Scholar

10. Knudsen HK, Ducharme LJ, Roman PM: Early adoption of buprenorphine in substance abuse treatment centers: data from the private and public sectors. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 30:363–373, 2006Google Scholar

11. Striegal-Moore R, Bulik C: Risk factors for eating disorders. American Psychologist 62:181–198, 2007Google Scholar

12. Bowers WA, Andersen AE, Evans K: Management of eating disorders: inpatient and partial hospital programs, in Clinical Handbook of Eating Disorders: An Integrated Approach. Edited by Brewerton TD. New York, Marcel Dekker, 2004Google Scholar