Use of Multiple Psychotropic Medications Among Adolescents Aging Out of Foster Care

The past several years have shown expansions in the use of psychotropic medications among children and adolescents in general and among those in the child welfare system in particular. However, much of this information comes from administrative claims data, which often lack information on clinical indications for such use.

Psychotropic medication prescriptions for children and adolescents have risen two- to threefold in the past decade. The risk of aggressive psychopharmacology is high among children in the child welfare system, of whom 40% to 60% are reported to meet criteria for at least one DSM-IV disorder ( 1 ). National probability estimates suggest that 14% of these children receive psychotropic medications—a rate two to three times that of children in the community ( 2 ).

Because of their complex patterns of need, psychopathology, and help-seeking pathways, children in child welfare may be at greater risk of using multiple concurrent psychotropic medications. Variably called concomitant use, coprescription, or polypharmacy, this concept is most commonly operationalized in the literature as use of two or more concurrent psychotropic medications. To the authors' knowledge, only one study has explicitly examined the use of multiple medications among children and adolescents in child welfare ( 3 ). Breland-Noble and colleagues, the authors of that study, reported that half of all adolescents in high-service-intensity and congregate care environments were taking multiple psychotropics, with approximately 15% of the overall sample taking four or more medications concurrently.

In an attempt to better understand patterns of multiple psychotropic medication use among adolescents in child welfare, we report data from interviews conducted among 406 adolescents who were aging out of foster care in a Midwestern state. We present data on the prevalence of using multiple psychotropic medication and sociodemographic and diagnostic factors associated with such use.

Methods

Participants for this study were recruited from eight counties in a Midwestern state between December 2001 and May 2003; all were age 17 and were in the custody of the state's child welfare agency ( 4 ). Consents were obtained from caseworkers of the adolescents, after which the adolescents provided assent. Interviewers administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV) ( 5 ) and conducted audits of medication containers to verify medication use patterns. Of a total of 450 adolescents eligible to participate in the study, 406 (90%) were interviewed. We report data from 403 of the adolescents who had complete records. This study was approved by Washington University's institutional review board.

Adolescents self-reported their age and race-ethnicity; interviewers recorded their gender as observed. Adolescents' self-reported place of residence was grouped into two categories—living in home (with birthparents or other relatives or independently) and living out of home (living in a foster home or group home). Physical abuse and physical neglect were elicited from responses to the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, a 28-item self-report instrument that elicits a lifetime history of maltreatment ( 6 ). A third category of sexual abuse was elicited from questions asking about past experiences of being touched on one's own—or being forced to touch another's—private parts and past experiences of forcible vaginal, anal, or oral sex.

Interviewers used the DIS-IV ( 5 ) to obtain past-year diagnoses of participants. Diagnostic information was obtained on presence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depressive disorder, manic episode, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and substance use disorder. We constructed a binary indicator variable of disruptive behavioral disorder for adolescents who met criteria for either conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder.

Adolescents reported past-month medication data in response to questions from the medication module of the Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents ( 7 ); responses were verified by audits of medication containers, wherever available. Adolescents also reported whether they received specialty services (from a mental health clinic, a community-based mental health provider, or a day treatment center) or nonspecialty services (from family physicians or internists).

Selection of variables for statistical analyses was informed by existing literature on medication use among children in welfare settings ( 2 , 8 , 9 ). We did not use age in the analyses because all adolescents in the sample were closely clustered around 17 years of age. We used chi square tests of proportion to examine associations between number of medications consumed and the predictors listed above. For multivariate analyses, we estimated a zero-inflated negative binomial regression model, which is designed for count data. We developed and tested interaction variables between diagnoses to assess medication use patterns for adolescents with comorbid or co-occurring disorders; these interactions were not significant and are not presented.

Results

Adolescents in our sample had a mean age of 17.0±.1 years, and 226 (56%) were female. Over half (N=206, or 51%) were African American, 177 (44%) were white, 14 (3%) were of mixed race, and the rest (N=6, or 1%) belonged to another race or ethnicity. Many (N=247, or 61%) reported a history of either physical abuse or physical neglect, and 140 (35%) had been sexually abused. Around half (N=181, or 45%) had at least one DSM-IV disorder, the most common ones being substance use disorder (N=72, or 18%) and major depressive disorder (N=71, or 18%). Most adolescents lived in a congregate care setting, such as a group home (N=168, or 42%) or in family foster care (N=116, or 29%). Others lived with relatives (N=74, or 18%), with their birthparents (N=33, or 8%), or independently (N=12, or 3%). A majority of adolescents (N= 255, or 63%) used specialty mental health services, three (<1%) saw nonspecialty providers, and 39 (10%) used both specialty and nonspecialty services.

A total of 257 adolescents (64%) reported that they were not taking any psychotropics, while 54 (13%) reported being on one medication, 46 (11%) reported being on two concurrent psychotropics, 21 (5%) reported being on three, 18 (4%) reported being on four, and seven (2%) reported being on five. Most adolescents who were taking only one medication were taking an antidepressant (N=34, or 63%), most commonly a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, usually sertraline. Adolescents who were taking two concurrent medications were taking either an antidepressant along with an antipsychotic (N=11, or 24%) or an antidepressant along with a mood stabilizer (N=10, or 22%). The most common antipsychotics consumed by adolescents in this study were second-generation antipsychotics (N=72, or 18%), usually olanzapine (N=25, or 6%); the most common mood stabilizers were anticonvulsants (N=55, or 14%), usually divalproex sodium (N=20, or 5%). These three were also the most commonly used drugs for adolescents taking three or more concurrent psychotropic medications (17 of 46 adolescents, or 37%).

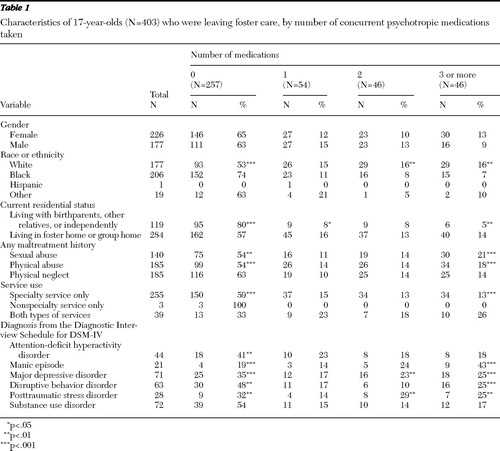

Bivariate analyses of adolescents' characteristics with number of medications are displayed in Table 1 . Race-ethnicity was significantly associated with number of medications consumed, with larger percentages of white adolescents taking two or more psychotropic medications. A smaller percentage of adolescents living out of home were taking one medication or three or more medications concurrently. Compared with adolescents without a history of sexual or physical abuse, a higher percentage of those with such a history were taking three or more psychotropics concurrently. Among adolescents taking three or more concurrent psychotropics, most (N=34, or 74%) reported using specialty mental health services only.

|

Almost half (N=9, or 43%) of all adolescents who met criteria for having had a manic episode and a quarter of those with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, disruptive behavior disorders, or PTSD were taking three or more concurrent medications. Forty-one percent (N=18) of those who met criteria for having ADHD were not taking any medications.

Multivariate analyses using all of the variables listed on Table 1 confirmed that adolescents with a history of physical abuse (relative risk [RR]= 1.9, 95% confidence interval [CI]= 1.3–2.6, p<.01) and those with a history of sexual abuse (RR=1.7, CI= 1.1–2.4, p<.01) had higher relative risks of taking more medications than adolescents without such a history (data not shown). Relative risks of multiple medication use were also significant among adolescents with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder (RR=1.7, CI=1.2–2.3, p<.001) and those with a diagnosis of a manic episode (RR=1.5, CI=1.1–2.2, p<.05). Sociodemographic and service-related variables were not associated with risks of multiple medication use.

Discussion and conclusions

This brief report presents novel, contextual data on the concurrent use of multiple psychotropic medications in a local cohort of older adolescents who were leaving the child welfare system. These findings suggest that one in ten adolescents in our cohort was taking three or more psychotropic medications concurrently; that antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers were the most common drugs consumed; and that a history of physical or sexual abuse and meeting criteria for having a diagnosis of a manic episode or a major depressive disorder put adolescents at high risk of polypharmacy.

Our findings on prevalence extend prior work examining rates of medication use among children in child welfare. Estimates of medication use among children in foster care in Los Angeles County conducted by Zima and colleagues ( 10 ) revealed a prevalence rate of medication use of 16%—half of our overall medication use rate of 36%. Two factors differentiate our study from that report. First, our sample is older by a mean of 7.5 years, and older age is a known risk factor for medication use ( 2 ). Second, our study was conducted in an area with far fewer mental health resources than Los Angeles County, and it is likely that our findings reflect the effects of these constraints on the close monitoring of medication use by these adolescents. Our rate of medication use is comparable to the 30% reported in a study using Medicaid claims data for children in foster care ( 11 ).

The uniqueness of our study, however, lies in its decomposition of multiple psychotropic medication use, a topic on which there is little empirical information about children and adolescents and no empirical information about those in the child welfare system. Studies conducted on Medicaid enrollees report rates of using two concurrent psychotropic medications as being between 14% ( 12 ) and 30% ( 13 ). Our findings reveal that 23% of adolescents are receiving two or more psychotropic drugs concurrently, and a small fraction is taking up to five medications concurrently—a practice pattern that can have serious consequences for their physical health.

Whether these patterns of medication use are inappropriate remains uncertain because of the challenges associated with interpreting appropriateness by looking only at the number of medications used. First, a numerical approach is not sensitive to such practices as the use of an anticholinergic agent to treat extrapyramidal side effects of a conventional antipsychotic. Second, such approaches do not distinguish between multiple medications for a single disorder and pharmacotherapy for comorbid or co-occurring disorders. Third, a counting approach is insensitive to augmentation strategies for treatment-resistant disorders. Our lack of chart data precludes conclusions regarding appropriateness of medication use observed in this study.

In contrast to another study that found that stimulants are the predominant psychotropic drug in multiple medication regimens of youths ( 13 ), we found higher rates of use of antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers in our sample. Our study found that among adolescents taking three or more concurrent psychotropic medications, most (N=37, or 80%) were taking an antipsychotic, usually olanzapine. This finding is consistent with recent trends toward increasing use of antipsychotic medications, especially second-generation antipsychotics ( 14 ). Several of the diagnoses that place adolescents at higher risk of polypharmacy are externalizing disorders; this suggests that clinicians may be attempting to gain control over behavioral symptoms through pharmacological means.

On the other hand, 18 (41%) adolescents who met diagnostic criteria for ADHD, 25 (35%) with major depressive disorder, and four (19%) with a manic episode did not receive any psychotropic drugs. Our lack of chart information means that we do not have a complete picture of respondents' past medication history and adherence patterns, which means that we do not have a complete explanation of why they were not currently using medications. However, these findings raise concern that there may be patterns of underutilization of medications for some adolescents, concurrent with overutilization for others.

This study has other limitations. First, most of our data on psychotropic medication use were elicited from respondents. The study design required interviewers to enhance the validity of self-report by examining medication containers, but these were unavailable in some cases. Second, this study was conducted in a Midwestern state, and its findings cannot be generalized to other communities with different health resources, practice patterns, and provider availability. Third, for reasons of generalizability and lack of chart information, we are unable to comment on the appropriateness of psychotropic drug prescribing among this cohort.

Despite these limitations, these data provide for the first time the diagnostic correlates of polypharmacy among adolescents aging out of foster care and provide preliminary data on a population at risk of multiple medication use. Careful diagnostic and behavioral assessment and close monitoring of these adolescents are necessary to ensure quality of their psychopharmacological care.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by grant R01-MH-61404 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. McMillen. Dr. Raghavan is an investigator with the Center for Mental Health Services Research, George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis, through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (5P30 MH-068579).

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Landsverk J, Garland AF, Leslie LK: Mental health services for children reported to child protective services, in APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment. Edited by Myers JEB, Berliner L, Briere J, et al. Thousand Oaks, Calif, Sage, 2002Google Scholar

2. Raghavan R, Zima BT, Andersen RM, et al: Psychotropic medication use in a national probability sample of children in the child welfare system. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 15:97–106, 2005Google Scholar

3. Breland-Noble AM, Elbogen EB, Farmer EM, et al: Use of psychotropic medications by youths in therapeutic foster care and group homes. Psychiatric Services 55:706–708, 2004Google Scholar

4. McMillen JC, Zima BT, Scott LD Jr, et al: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older youths in the foster care system. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 44:88–95, 2005Google Scholar

5. Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz KK, et al: Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV). St Louis, Mo, Washington University, 2000Google Scholar

6. Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, et al: Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:340–348, 1997Google Scholar

7. Stiffman AR, Horwitz SM, Hoagwood K, et al: The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA): adult and child reports. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 39:1032–1039, 2000Google Scholar

8. McMillen JC, Scott LD, Zima BT, et al: Use of mental health services among older youths in foster care. Psychiatric Services 55:811–817, 2004Google Scholar

9. Zima BT, Bussing R, Yang X, et al: Help-seeking steps and service use for children in foster care. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 27:271–285, 2000Google Scholar

10. Zima BT, Bussing R, Crecelius GM, et al: Psychotropic medication treatment patterns among school-aged children in foster care. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 9:135–147, 1999Google Scholar

11. DosReis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, et al: Mental health services for youths in foster care and disabled youths. American Journal of Public Health 91:1094–1099, 2001Google Scholar

12. Martin A, Van Hoof T, Stubbe D, et al: Multiple psychotropic pharmacotherapy among child and adolescent enrollees in Connecticut Medicaid managed care. Psychiatric Services 54:72–77, 2003Google Scholar

13. DosReis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, et al: Multiple psychotropic medication use for youths: a two-state comparison. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 15: 68–77, 2005Google Scholar

14. Olfson M, Blanco C, Liu L, et al: National trends in the outpatient treatment of children and adolescents with antipsychotic drugs. Archives of General Psychiatry 63:679–685, 2006Google Scholar