Antidepressant Use in Black and White Populations in the United States

Mental disorders are leading causes of disability in the United States ( 1 ). Antidepressant medications are a mainstay of treatment for depressive and anxiety disorders ( 2 ). However, many people, particularly those in racial and ethnic minority groups, do not receive effective treatment ( 3 , 4 , 5 ). Substantial racial and ethnic differences in access to and quality of mental health care have been reported, including antidepressant pharmacotherapy ( 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ), and the general undertreatment of mental disorders is even greater for black Americans ( 11 ). Previous reports have indicated that less than half of black Americans with depressive conditions were prescribed antidepressants compared with about two-thirds of white Americans ( 5 , 12 ). These differences in mental health care may contribute to the persistence and severity of mental disorders and the burden of nonlethal suicidality among black Americans ( 13 , 14 ). Understanding some of the reasons for the racial and ethnic differences in antidepressant use could inform methods for improving access to mental health care.

A substantial proportion of individuals who met criteria for mental disorders in the past 12 months have been found not to receive mental health services; however, the types of therapies used or not used (including psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy) are not specified ( 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ). Studies specifying antidepressant therapy have indicated that many drugs were prescribed for non-mental health indications and that nearly half of all antidepressant users did not meet criteria for current psychiatric disorders ( 19 , 20 , 21 ). Furthermore, previous work has shown that several common medical conditions, such as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease and risk factors for these conditions, are associated with depressive symptomatology and antidepressant use ( 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ). Given the prominence of antidepressant drugs for treating common mental conditions and the rise in the number of prescriptions and associated costs in the United States over the past decade, we sought to examine the distribution of antidepressant use at the national level ( 2 ). To better understand factors for antidepressant use among ethnic and racial groups, we applied a modification of Andersen's behavioral model of health services use to large, nationally representative samples of black and non-Latino white Americans ( 26 , 27 ). The behavioral model posits three major factors—predisposing, health need, and enabling factors—related to accessing health services. We anticipated that these factors, particularly health need, would be associated with access to mental health services (specifically, antidepressants).

Methods

Data collection

The National Institute of Mental Health's Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES) initiative combined data from several nationally representative studies: the National Survey of American Life (NSAL), the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R) and the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS). Data from only the NSAL and NCS-R were used in this study. Sampling weights created by CPES staff enable analyses of pairs of studies within the CPES, which allows population estimates that are specific to populations of interest ( 28 ). Data were collected by the Survey Research Center of the University of Michigan. The institutional review board of Wayne State University approved this study.

We used face-to-face computer-assisted interviews to collect data from integrated national household probability samples of noninstitutionalized adults after receiving informed, written consent from the respondents. Specially trained interviewers who were not clinicians administered the World Mental Health (WMH) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) to respondents ( 29 ). Fair to good concordance values have been reported between nonclinician-administered WMH-CIDI interviews and clinician-administered Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV reappraisals in the NSAL and NCS-R ( 13 , 15 , 30 ). The NSAL data were collected between February 2001 and June 2003. A total of 6,082 adults age 18 and over who self-identified as African Americans (N=3,570), blacks of Caribbean descent (N=1,621), and non-Hispanic whites (N=891) participated. The overall NSAL response rates were 72.3% for blacks (70.7% for the African American sample and 77.7% for Caribbean blacks) and 69.7% for whites.

NCS-R data were collected between February 2001 and April 2003. Part 1 of the survey included a core diagnostic assessment lasting approximately one hour and administered to all respondents. Part 2 included questions about mental health risk factors and problems, other variables, and additional disorders. To reduce respondent burden and control study costs, part 2 was administered to 5,692 of the 9,282 part 1 respondents, including all part 1 respondents with a lifetime mental disorder and a probability subsample of all other respondents. The overall NCS-R response rate was 71%. Final response rates for the sample designs of the NSAL and NCS-R were computed according to the best-practice guidelines of the American Association of Public Opinion Research, which call for incorporating disproportionate sampling, household screening, and two-phase sampling for follow-up with nonresponders ( 31 ).

Analysis of subpopulations

We analyzed specific subpopulations of the NSAL and NCS-R data sets. The NSAL subpopulation (N=4,826) was limited to 3,424 African Americans and 1,402 Caribbean black respondents who had sufficient medication information for assessment of their antidepressant use in the prior 12 months (past year); this subpopulation represented 96.4% (a sample-weighted proportion) of the original African-American and Caribbean black NSAL respondents. Because of cost limitations, white participants in the NSAL were not questioned about medication use and therefore were not available for these analyses. Because the NSAL wide-area sampling procedures were used to survey black individuals living in areas with high and low densities of black populations, the NSAL data represented a unique sample that was highly representative of black Americans at the time of data collection ( 32 ).

The NCS-R subpopulation (N=4,897) was limited to the non-Latino whites (N=4,180) and the blacks (679 African Americans and 38 Caribbean blacks) who had sufficient medication, psychosocial, and other correlate information.

Measures

In both the NSAL and NCS-R, antidepressant drug use was determined by responses to the question "Did you take any type of prescription medicine in the past year for problems with your emotions, substance use, energy, concentration, sleep, or ability to cope with stress? Include medicines even if you took them only once." In addition, interviewers recorded generic and trade names of prescription antidepressants from pill bottles during interviews. The prescription drug use question in the NSAL appeared before a section of the interview on the use of mental health services; it appeared after the mental health services section in the NCS-R. Generic and trade names were reviewed by two board-certified psychiatrists and a psychiatric nurse specialist to verify that the drugs were antidepressants before drug coding for the analyses.

This study used DSM-IV criteria for past-year and lifetime major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and five specific anxiety disorders (agoraphobia without panic, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and social phobia). With few exceptions, these psychiatric disorders are Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved indications for antidepressant use ( 33 ). They are also among the most common mental disorders, they are associated with high levels of disease burden in the United States, they frequently coexist, and they are often misdiagnosed ( 1 , 34 ). The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology Self-Report (QIDS-SR) was used to measure symptom severity during the worst two-week period of the past year ( 35 ). Respondent scores were summed across all domains and mapped onto the framework of the full Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology scale with the use of conversion algorithms developed for the QIDS-SR ( 36 ). The final converted score was divided into two levels of depressive symptom severity: mild and moderate to severe. This dichotomy was used to reflect practice guidelines for antidepressant use in depression care ( 37 ). Severity of anxiety disorders was not examined because practice guidelines were not available for all five anxiety disorders.

Variables

The primary outcome variable in the analyses was past-year antidepressant use as indicated by self-report or medication inventory. Independent variables included indicators of meeting diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder, dysthymia, or anxiety disorders in the past 12 months. Additional independent variables included self-reported diagnostic histories of medical conditions, gender, age, family income, years of education, and health insurance status (insured and uninsured). Health insurance coverage included Medicare, Medicaid, or Tricare-CHAMPUS, current or former employee-based coverage, and coverage purchased directly from an insurance company (including group purchasing, such as the American Association of Retired Persons). Categorical variables were created for age (18–34, 35–64, and over 64 years), family income (less than $18,000, $18,000–$31,999, $32,000–$54,999, and $55,000 and over), and education (0–11, 12, 13–15, and 16 or more years).

Analytic approach

Procedures designed for subpopulation analysis of complex sample survey data in the Stata software package were used for all analyses ( 38 ). All statistical estimates were weighted with NSAL and NCS-R sampling weights to account for individual-level unequal probabilities of selection into the samples, individual nonresponse, and additional poststratification to ensure population representation ( 31 ). A Taylor series linearization approach to variance estimation ( 39 ) was used to account for the complex multistage clustered design of the samples when computing estimated standard errors.

Sample estimates describing the prevalence of past-year antidepressant use for black and white populations were calculated in subgroups on the basis of individual-level characteristics, including diagnoses, sociodemographic characteristics, and medical conditions. Design-based F tests derived from the Rao-Scott chi square test were conducted to compare the prevalence of antidepressant use between the two ethnic groups in these different subgroups ( 40 ). Multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate the relationships of the combined past-year diagnoses, sociodemographic factors, and medical conditions with the odds of antidepressant use, after the analyses controlled for the other covariates in the models. Odds ratios expressing the relative influences of the covariates on the odds of antidepressant use were estimated on the basis of multivariate logistic regression models in addition to design-based 95% confidence intervals. Additional multivariate logistic regression models considered the correlates of past-year antidepressant use by "healthy" respondents, or those without past-year diagnoses of depressive or anxiety disorders. Interactions between race (white or black) and the other correlates in the logistic regression models were examined to assess whether racial differences in past-year antidepressant use were being moderated by the other correlates under consideration.

Results

Prevalence estimates of antidepressant use in the past year

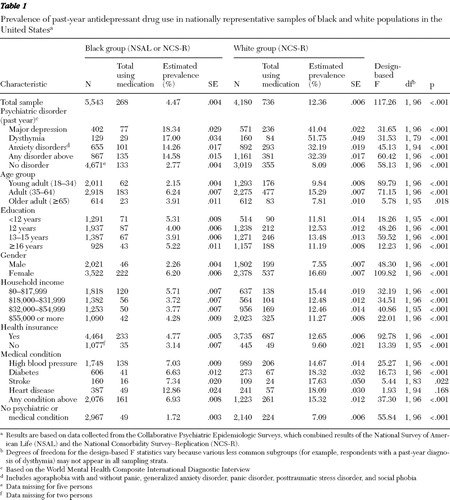

Overall, black respondents had a significantly lower prevalence of past-year antidepressant use than white respondents (4.5% compared with 12.4%) ( Table 1 ). Antidepressant use by black respondents who met DSM-IV criteria for major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and anxiety disorders in the past year was significantly lower compared with white counterparts. About half of all antidepressant use was by black persons (53.2%, sample weighted) and white persons (53.4%, sample weighted) not meeting criteria for any of the psychiatric disorders we examined. At every level of age, education, household income, gender, and health insurance coverage status, the prevalence of past-year antidepressant use was significantly lower for the black population compared with the white population. Among respondents with specific medical conditions, black respondents again had significantly lower prevalence of antidepressant use compared with white respondents, with the exception of respondents having a history of heart disease. Finally, among individuals without mental or medical conditions considered in this study, black persons had significantly lower antidepressant use than whites.

|

Predictors of antidepressant use

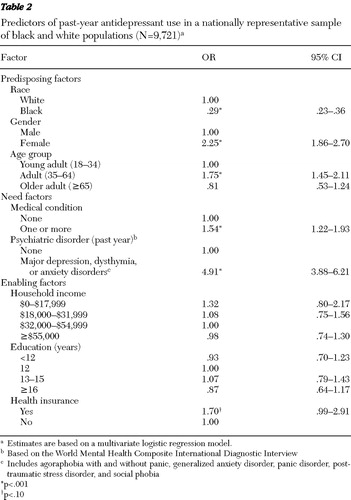

Table 2 presents results from fitting a multivariate logistic regression model to past-year antidepressant use. Among potential predisposing factors, being black was associated with significantly lower odds of antidepressant use compared with being white, whereas being female and middle-aged increased the odds of antidepressant use. Need factors (that is, any past-year depressive or anxiety disorder and the presence of any of the four medical conditions examined) significantly increased the odds of past-year antidepressant use. One enabling factor, health insurance coverage, was marginally associated with increased antidepressant use. Interactions between predisposing, need, and enabling factors (such as health insurance) were tested, but their interactions with antidepressant use were not significant (data not shown but available on request).

|

Depression severity

The prevalence of moderate to severe depression was similar among black and white respondents, which is consistent with previous findings by Williams and colleagues ( 13 ). Antidepressant use by depression severity levels based on the QIDS data were examined. The proportions of antidepressant use by black respondents with mild depression (N=3, or 13.5%) or moderate to severe depression (N=48, or 17.6%) were similar; however, antidepressant use among white respondents with mild depression (N=13, or 21.6%) and moderate to severe depression (N=153, or 40.3%) was significantly different ( χ2 =10.12, df=142, p=.003).

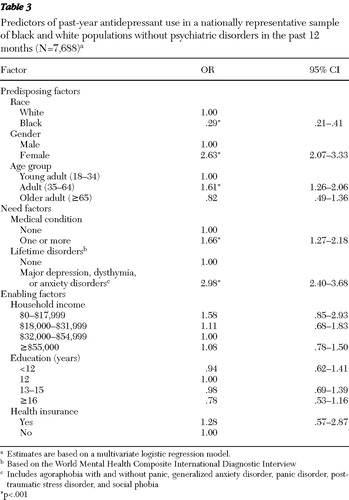

Antidepressant use with no past-year depressive or anxiety disorders

About half of all the antidepressants inventoried were used by respondents not meeting criteria for past-year depressive or anxiety disorders. To better understand the predictors of antidepressant use among these respondents, we excluded respondents who met criteria for major depression, dysthymia, or anxiety disorders in the past year in the analyses shown in Table 3 . Being black (a predisposing factor) was associated with significantly lower odds of past-year antidepressant use compared with being white. Being of middle age and being female (other predisposing factors) significantly increased the odds of antidepressant use. Lifetime depressive and anxiety disorders and having any of the medical conditions we examined (need factors) also significantly increased the odds of past-year antidepressant use. None of the enabling factors were significant in this model, and no significant interactions were found (data not shown).

|

Discussion

We found that who you are matters with regard to antidepressant use in the United States. Nationwide, black Americans with depressive or anxiety disorders were one-third less likely than white Americans to have used antidepressants. Psychiatric need (in terms of symptom severity) was associated with more antidepressant use for white Americans but not for black Americans. Antidepressant use was also associated with medical conditions related to vascular disease; however, these associations were independent of coexisting psychiatric conditions. Finally, we found evidence that many antidepressants may be used for maintenance pharmacotherapy of past depressive and anxiety disorders.

The racial differences in antidepressant use we found are much larger compared with previous reports, and we suggest some possible explanations ( 5 , 6 , 12 ). First, respondents were selected into the NSAL and NCS-R regardless of medical care access, in contrast to clinic-based or administrative data, which are often restricted to populations that have used medical care services. This has particular importance for ethnic minority populations. Black Americans who are not elderly (21%) are nearly twice as likely as white counterparts (13%) to lack health insurance and other factors that enable access to care and thus would likely be excluded from administrative and clinic-based studies ( 41 ). In this study insurance coverage was only modestly associated with antidepressant use. Nevertheless, systematically excluding a large portion of uninsured individuals could introduce selection bias that could inflate treatment rate estimates.

Second, attempts to explain the comparatively lower use of mental health services by black Americans have focused on racial differences in preferences for social support or alternative treatments ( 42 , 43 ). Although these hypotheses are plausible, other explanations should be considered ( 13 , 44 ). For example, most Americans receive mental health treatment in busy primary care settings where recognition and treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders can be difficult, particularly for black patients ( 45 ). Physicians providing care for black patients report being less well-trained and having less access to important clinical resources and specialists than those who treat white patients ( 46 ). The finding that depression severity was related to antidepressant use for white respondents but not black respondents is consistent with the hypothesis that the quality of mental health care available to black Americans is inferior. The large differences in antidepressant use suggest unmet need that may stem from substandard and unaffordable health care encountered by black Americans ( 47 , 48 ). Attitude and preference differences for antidepressants between black and white populations may also explain these findings. Research suggests that antidepressant treatment is less acceptable to black persons than to white persons ( 43 ). For instance, Givens and colleagues ( 49 ) found that black persons were more likely to prefer counseling to taking antidepressants. Additional work is needed to determine the degree to which the differences between black and white populations in antidepressant use we found result from unmet need, differences in attitudes, and preference for treatment or some combination of these and other factors.

Psychiatric need increased the odds of antidepressant use, but so did the presence of common medical conditions associated with vascular disease. Medical "need" in the form of risk factors for vascular disease also predicted antidepressant use in this study. Mental disorders are associated with medical conditions, particularly vascular disease; however, the causal nature of the associations is not fully clear. As previously suggested, vascular disorders may be directly associated with the etiology of some forms of depressive conditions ( 50 ). Furthermore, symptoms of medical conditions may mimic clinical depression, which could lead to antidepressant use. Medical illnesses represent acute stressors that may tip the balance for some individuals and their families toward mental disorder symptomatology that may elicit antidepressant use. Alternatively, it is possible that persons with medical conditions have more contact with health care providers, which would increase the likelihood that their depressive symptoms will be detected and treated. It is clear from our findings that the medical conditions we examined were independently associated with antidepressant use.

Consistent with previous studies, we found that mental disorders in the past year accounted for only about half of antidepressant use ( 16 , 51 , 52 ). Lifetime depressive and anxiety disorders accounted for a substantial portion of the antidepressant use by individuals not meeting criteria for disorders in the past year. Our findings may reflect the growing awareness and practice by clinicians that psychiatric need may extend beyond the acute phase of these chronic conditions. It remains to be determined whether the benefits and potential harm of maintenance pharmacotherapy represent sound preventive clinical practice or excessive prescribing practice.

Together, past-year and lifetime depressive and anxiety disorders and medical conditions accounted for 83.3% of all antidepressant use by black and white Americans. This indicates that about one-fifth of antidepressant use may be for other reasons (such as smoking cessation). Mental health cost estimates based solely on antidepressant prescriptions without considering other clinical indications could inflate estimates by as much as 20%. The reasons for antidepressant use among those not meeting criteria for depressive and anxiety disorders require additional investigation.

This study used sophisticated sampling procedures that make it the largest and most inclusive study of antidepressant use among black and white Americans. Although the results are most likely the best estimates to date, they should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, the NSAL and NCS-R excluded homeless or institutionalized persons, which could underestimate the unmet need for treatment of depressive and anxiety disorders. Second, systematic survey nonresponse or selection bias could have had untoward effects on our national estimates ( 18 ). Third, as a diagnostic instrument, the WMH-CIDI has a modest sensitivity and high specificity for detecting "true" psychiatric disorders (such as major depression) among NSAL and NCS-R respondents ( 13 , 15 ). Thus it is likely that some cases with "true" psychiatric disorders were missed, which could inflate the proportion of respondents without mental disorders using antidepressants. Fourth, research indicates that self-reports of mental health service use often overestimate actual use ( 52 ). Because self-reported use of antidepressants was corroborated with pill-bottle inventories, this potential bias was minimized.

Fifth, the medication questions in the NSAL appeared immediately before a section of the interview on the use of mental health services, whereas the same questions appeared after the same section in the NCS-R. This difference may have increased antidepressant reporting among black respondents and attenuated reporting by white respondents. If such bias was introduced into this comparative study, we may have underestimated the black-white differences in antidepressant use by increasing the estimates for black respondents and lowering the estimates for white respondents. In addition, other FDA-approved indications for antidepressants (such as for treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder and eating disorders) were not considered in this study, which could account for some of the antidepressant use among respondents not meeting criteria for depression or anxiety disorders.

Finally, psychosocial treatments were not considered in this report but are needed to estimate unmet mental health need. On the other hand, antidepressants are by far the most common form of therapy for depressive and anxiety disorders ( 2 , 3 ). Given the magnitude of unmet need that we observed, the main inferences of our work would be unlikely to change dramatically had we included psychosocial treatments.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest several directions for future research and policy to improve delivery of mental health care for black and white Americans. First, increased availability and initiation of mental health treatment will require new outreach efforts to underserved patients and clinicians who serve those patients. Second, improving mental health care at common points of service delivery (such as primary care) may be needed. Collaborative care models show promise for improving care among diverse populations, as well as improving patient outcomes and clinician satisfaction, while containing costs ( 53 , 54 ). Finally, new independent research may be needed to explore the potential value of antidepressant treatment for medical conditions other than the primary indications of depressive and anxiety disorders.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), and the National Institute on Aging (NIA). Dr. González is supported by NIMH grant MH-67726 and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Network for Multicultural Research on Health and Healthcare. Dr. Williams is supported by NIMH grant MH-59575. Dr. Taylor is supported by NIA grant AG-18782. Dr. Hinton is supported by NIA grant AG-19809. Dr. Jackson and the National Survey of American Life are supported by NIMH grant MH-57716 and by NIA grant AG-15281. The authors express their sincere thanks to Susan L. González, M.N., R.N., for assistance with reviewing medications, Jamie Abelson, M.S.W., and Julie Sweetman, M.A., for data and technical support, and Willie Underwood III, M.D., and Mary E. Bowen, Ph.D., for editing. This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Dr. Croghan receives research funding from Forest Laboratories and Eli Lilly and Company. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. McKenna MT, Michaud CM, Murray CJ, et al: Assessing the burden of disease in the United States using disability-adjusted life years. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 28:415–423, 2005Google Scholar

2. Zuvekas SH: Prescription drugs and the changing patterns of treatment for mental disorders, 1996–2001. Health Affairs 24: 195–205, 2005Google Scholar

3. Croghan TW, Schoenbaum M, Sherbourne CD, et al: A framework to improve the quality of treatment for depression in primary care. Psychiatric Services 57:623–630, 2006Google Scholar

4. Perez-Stable EJ, Miranda J, Munoz RF, et al: Depression in medical outpatients: underrecognition and misdiagnosis. Archives of Internal Medicine 150:1083–1088, 1990Google Scholar

5. Harman JS, Edlund MJ, Fortney JC: Disparities in the adequacy of depression treatment in the United States. Psychiatric Services 55:1379–1385, 2004Google Scholar

6. Melfi CA, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, et al: Racial variation in antidepressant treatment in a Medicaid population. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:16–21, 2000Google Scholar

7. Swartz MS, Wagner HR, Swanson JW, et al: Administrative update: utilization of services: I. comparing use of public and private mental health services: the enduring barriers of race and age. Community Mental Health Journal 34:133–144, 1998Google Scholar

8. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity—A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 2001Google Scholar

9. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR: Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC, Institute of Medicine, Board on Health Sciences Policy, 2002Google Scholar

10. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar

11. Neighbors HW, Caldwell C, Williams DR, et al: Race, ethnicity, and the use of services for mental disorders: results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:485–494, 2007Google Scholar

12. Miranda J, Cooper LA: Disparities in care for depression among primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine 19:120–126, 2004Google Scholar

13. Williams DR, González HM, Neighbors H, et al: Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:305–315, 2007Google Scholar

14. Joe S, Baser RE, Breeden G, et al: Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts among blacks in the United States. JAMA 296:2112–2123, 2006Google Scholar

15. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289:3095–3105, 2003Google Scholar

16. Druss BG, Wang PS, Sampson NA, et al: Understanding mental health treatment in persons without mental diagnoses: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:1196–1203, 2007Google Scholar

17. Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al: Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291:2581–2590, 2004Google Scholar

18. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar

19. Bouhassira M, Allicar MP, Blachier C, et al: Which patients receive antidepressants? A "real world" telephone study. Journal of Affective Disorders 49:19–26, 1998Google Scholar

20. Stone KJ, Viera AJ, Parman CL: Off-label applications for SSRIs. American Family Physician 68:498–504, 2003Google Scholar

21. Pomerantz JM, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, et al: Prescriber intent, off-label usage, and early discontinuation of antidepressants: a retrospective physician survey and data analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:395–404, 2004Google Scholar

22. Joynt KE, O'Connor CM: Lessons from SADHART, ENRICHD, and other trials. Psychosomatic Medicine 67(suppl 1):S63–S66, 2005Google Scholar

23. Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Talajic M, et al: Five-year risk of cardiac mortality in relation to initial severity and one-year changes in depression symptoms after myocardial infarction. Circulation 105:1049–1053, 2002Google Scholar

24. González HM, Hinton L, Ortiz T, et al: Antidepressant class and dosing among older Mexican Americans: application of geropsychiatric treatment guidelines. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 14:79–83, 2006Google Scholar

25. Herbst S, Pietrzak RH, Wagner J, et al: Lifetime major depression is associated with coronary heart disease in older adults: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychosomatic Medicine 69:729–734, 2007Google Scholar

26. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1–10, 1995Google Scholar

27. Cook BL, McGuire T, Miranda J: Measuring trends in mental health care disparities, 2000–2004. Psychiatric Services 58:1533–1540, 2007Google Scholar

28. Pennell BE, Bowers A, Carr D, et al: The development and implementation of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, the National Survey of American Life, and the National Latino and Asian American Survey. JAMA 13:241–269, 2004Google Scholar

29. Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, et al: Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMHCIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13: 122–139, 2004Google Scholar

30. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-1/NP). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1997Google Scholar

31. Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, et al: Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES). JAMA 13:221–240, 2004Google Scholar

32. Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, et al: The National Survey of American Life: A study of racial, ethnic, and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:196–207, 2004Google Scholar

33. Ables AZ, Baughman OL III: Antidepressants: update on new agents and indications. American Family Physician 67:547–554, 2003Google Scholar

34. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:617–627, 2005Google Scholar

35. Rush AJ, Gullion CM, Basco MR, et al: The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychological Medicine 26:477–486, 1996Google Scholar

36. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, et al: The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biological Psychiatry 54:573–583, 2003Google Scholar

37. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

38. Stata Statistical Software (Release 10). College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 2007Google Scholar

39. Rust K: Variance estimation for complex estimators in sample surveys. Journal of Official Statistics, 1:381–397, 1985Google Scholar

40. Rao JNK, Scott AJ: On chi-squared tests for multi-way tables with cell proportions estimated from survey data. Annals of Statistics 12:46–60, 1984Google Scholar

41. Current Population Series, vol 15. Washington, DC, US Bureau of the Census, 2006Google Scholar

42. Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Powe NR, et al: Mental health service utilization by African Americans and whites: the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area Follow-Up. Medical Care 37:1034–1045, 1999Google Scholar

43. Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al: The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Medical Care 41:479–489, 2003Google Scholar

44. Schnittker J, Pescosolido BA, Croghan TW: Are African Americans really less willing to use health care? Social Problems 52:255–271, 2005Google Scholar

45. Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, et al: Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? Journal of General Internal Medicine 15: 381–388, 2000Google Scholar

46. Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, et al: Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. New England Journal of Medicine 351:575–584, 2004Google Scholar

47. Williams DR, Jackson PB: Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Affairs 24:325–334, 2005Google Scholar

48. Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, et al: Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine 12:431–438, 1997Google Scholar

49. Givens JL, Katz IR, Bellamy S, et al: Stigma and the acceptability of depression treatments among African Americans and whites. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22:1292–1297, 2007Google Scholar

50. Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al: "Vascular depression" hypothesis. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:915–922, 1997Google Scholar

51. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85–94, 1993Google Scholar

52. Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al: Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine 352:2515–2523, 2005Google Scholar

53. Katon W, Unützer J, Fan MY, et al: Cost-effectiveness and net benefit of enhanced treatment of depression for older adults with diabetes and depression. Diabetes Care 29:265–270, 2006Google Scholar

54. Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al: Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Archives of Internal Medicine 166:2314–2321, 2006Google Scholar