Mental Health Services for Homebound Elders From Home Health Nursing Agencies and Home Care Agencies

Estimates of how many elderly persons are homebound range from 10.3 percent to more than 30.0 percent ( 1 , 2 ). Homebound elders are at increased risk of psychiatric illness, and their mental health needs have not been met. Epidemiologic studies have reported a higher prevalence of cognitive disorders, major depression, dysthymia, and anxiety disorders among homebound elderly persons ( 1 , 2 ). In a visiting nurse service agency, a structured diagnostic interview showed that 13.5 percent of the 539 patients had major depression ( 3 ).

Although psychiatric disorders are highly prevalent among homebound elderly persons, home health agencies may themselves act as barriers to care. A 1989 study reported that only one in four home health agencies provided mental health care ( 4 ). A 1999 study found a high prevalence of psychotropic medication use among homebound elders, much of which was inappropriately prescribed, in particular benzodiazepines, sedatives, and tricyclic antidepressants ( 5 ). More recently Bruce and colleagues ( 3 ) found that among 73 persons who were homebound with major depression, only a minority, 22 percent, were receiving antidepressants, and of these 31 percent received subtherapeutic dosages.

The aim of this study was to examine the practices of Rhode Island home care agencies and home health nursing agencies regarding management of mental health issues.

Methods

All home care agencies and home health nursing agencies licensed by the Rhode Island Department of Health were surveyed in 2003. Home care agencies are defined as those that provide supportive services—such as housekeeping, meal preparation, personal assistance, live-in attendants, and companions—but not direct health care services. Home health nursing agencies are those that provide nursing and at least one of the following services: occupational, physical, and speech therapies; medical and social services; and home health aides.

The survey inquired into whether the agencies identified elderly patients with a psychiatric problem and how they managed them. The questionnaire asked whether the agencies provided any mental health services, the nature of those services, and whether they made referrals to a psychiatrist or mental health clinic. The questionnaire also inquired into the management of individuals under their care who had dementia and serious behavioral problems.

The questionnaires were initially mailed to the agency's director. Agencies that did not respond to the mailed survey were interviewed over the telephone. Items that required clarification or were left unanswered from the initial mailing were completed in a follow-up telephone interview with the agency's director.

Results

Of the 54 agencies contacted, 53 responded; 18 were home care agencies and 35 were home health nursing agencies. The only agency that did not respond was a nursing agency specializing in intravenous services. Most of the home health nursing agencies participated in Medicare (25 agencies, or 71 percent); 30 (86 percent) participated in Medicaid, and 26 (74 percent) accepted third-party carriers. Most of the home care agencies were not providers in any insurance plan; seven (39 percent) accepted Medicare, eight (44 percent) participated in Medicaid, and five (28 percent) were reimbursed by third-party insurance carriers.

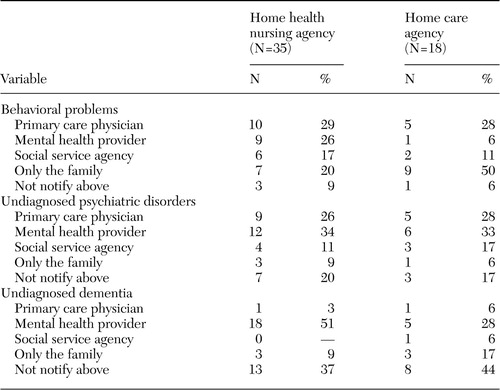

As shown in Table 1 , when a patient with an undiagnosed psychiatric disorder was encountered, 26 percent of the nursing agencies and 28 percent of the home care agencies said that they would notify the individual's primary care physician. Referral to a mental health provider, regardless of whether the provider made home visits, was an action proposed by 34 percent of the home health nursing agencies and 33 percent of the home care agencies. The remainder of the facilities stated that they would notify a social service agency, notify only the family, or neither of these options.

|

When behavioral problems, such as yelling, hitting, and other forms of agitation were seen, 29 percent of the home health nursing agencies and 28 percent of the home care agencies would refer the patient to a primary care physician. A referral to mental health services would be considered by 26 percent of the home health nursing agencies and 6 percent of the home care agencies. Twenty percent of the home health nursing agencies and 50 percent of the home care agencies would notify only the family without providing any referral recommendation.

If undiagnosed dementia was suspected, most of the home health nursing agencies (51 percent) would refer the patient to a mental health provider: 16 (46 percent) would refer the patient to a psychiatric nurse, and two (6 percent) would refer the patient to a mental health center. Five home care agencies (28 percent) would recommend referral to a mental health provider; however, all five of these agencies said that their referral would be to only a psychiatric nurse. The primary care physician was seldom considered. However, a sizable percentage of the agencies stated that they would take no action by not notifying anyone (37 percent of the home health nursing agencies and 44 percent of the home care agencies).

Only a small percentage of the home health nursing agencies and home care agencies reported that they could provide some kind of mental health services—such as a social worker or psychiatric nurse or referral to a psychiatrist—to individuals identified as in need of assistance (nine home health nursing agencies, or 26 percent, compared with four home care agencies, or 22 percent). A psychiatric nurse was on the staff of only eight home health nursing agencies (23 percent). The agency directors were specifically asked if they would refer a patient with an undiagnosed psychiatric disorder to a psychiatrist or mental health clinic; 14 home health nursing agencies (40 percent) and eight home care agencies (44 percent) stated that they would not. This response is in contrast to the response to the earlier question in which 35 agencies (66 percent) stated that patients should be referred to someone other then a mental health professional when an undiagnosed psychiatric problem was encountered. Because the patients seen by these agencies were homebound and frequently unable to arrange transportation, most of the home health nursing agencies (20 agencies, or 57 percent), and one-third of the home care agencies (six agencies, or 33 percent) reported that they would help arrange transportation for their patients to see a psychiatrist, regardless of whether the agency was willing to refer patients to a mental health provider.

One-fifth of the home health nursing agencies (eight agencies, or 23 percent) were able to identify one or more psychiatrists who manage their patients, whereas only one of the home care agencies (6 percent) could identify a psychiatrist. Of the nine agencies that identified psychiatrists, five (56 percent) reported that the psychiatrist would provide only a one-time consultation on the basis of the agency's request. Three of the psychiatrists (3 percent) who were identified conducted home visits and would provide consultation to the nursing staff over the telephone.

Many of the agencies stated that they would not accept homebound elderly clients identified with a primary psychiatric problem (19 home health nursing agencies, or 54 percent, compared with ten home care agencies, or 56 percent). However, all agencies would accept dementia as a primary diagnosis, because most agencies did not consider dementia to be a psychiatric disorder (19 home health nursing agencies, or 54 percent, compared with 14 home care agencies, or 78 percent).

Discussion and conclusions

Despite the high prevalence of psychiatric disorders among homebound elderly persons, those in need of mental health care are frequently not treated. We found a bias against accepting patients who have primary psychiatric disorders into home care programs. Response to behavioral problems or undiagnosed disorders, including dementia, were frequently ignored or left to the family to address. Although all patients in home care had an identified primary care physician, notification of the physician of suspected behavioral problems and disorders was not the norm. It is unclear as to why there is a reluctance to notify physicians; however, issues of stigma, poor mental health, literacy, and even agency policy need to be examined. The lack of response to psychiatric disorders by these agencies creates an additional barrier to care.

Few of the home health nursing agencies actually had psychiatric nurses. The lack of home health nurses with geriatric experience, as well as mental health training, has been associated with poorer identification of psychiatric disorders ( 6 ). Improving detection of depression—for example, by using screening scales—with care management protocols among elderly persons who receive home health nursing has been shown to improve outcome and decrease hospitalization ( 7 ). Home health care nurses complete extensive mandatory patient assessments that include symptoms of depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment, making inclusion of additional assessment protocols burdensome ( 8 ). Therefore, training home care personnel in detection and encouraging appropriate referral may be more feasible than using enhanced diagnostic tools.

Unfortunately, implementation of programs that address the needs of homebound elderly persons with mental illness is limited by financial barriers. Medicare does not reimburse nursing agencies at a rate coinciding with the increased time needed to conduct a mental health assessment, thereby creating a disincentive for these agencies to care for patients with primary psychiatric disorders. This rate of reimbursement is in contrast to the rate in the early 1990s when there was a brief expansion of psychiatric home health care before a change in Medicare reimbursement rules. The base rate of reimbursement per case that followed led to a rapid reduction in available mental health services. In addition, many persons in need of in-home mental health care do not meet Medicare criteria for being considered homebound ( 9 ). Similarly, financial barriers limit geriatric psychiatrists from going on house calls or consulting with home care agencies ( 10 ). Further research is needed with controlled randomized studies, demonstrating reduction of the mental health burden to homebound elderly persons and associated economic and medical benefits of home visits.

1. Ganguli M, Fox A, Gilby J, et al: Characteristics of rural homebound older adults: a community-based study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 44:363-370, 1996Google Scholar

2. Bruce ML, McNamra R: Psychiatric status among the homebound elderly: an epidemiologic perspective. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 40:561-566, 1992Google Scholar

3. Bruce ML, McAvay GJ, Raue PJ, et al: Major depression in elderly home health care patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1367-1374, 2002Google Scholar

4. Harper MS: Providing mental health services in the homes of the elderly: a public policy perspective. Caring 8:4-6, 8-9, 52-53, 1989Google Scholar

5. Golden AG, Preston RA, Barnett SD, et al: Inappropriate medication prescribing in homebound older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 47:948-953, 1999Google Scholar

6. Brown EL, McAvay G, Raue PJ, et al: Recognition of depression among elderly recipients of home care services. Psychiatric Services 54:208-213, 2003Google Scholar

7. Flaherty JH, McBride M, Marzouk S, et al: Decreasing hospitalization rates for older home care patients with symptoms of depression. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 46:31-38, 1988Google Scholar

8. Raue PJ, Brown EL, Bruce ML: Assessing behavioral health using OASIS: part 1: depression and suicidality. Home Healthcare Nurse 20:154-161, 2002Google Scholar

9. Kohn R, Goldsmith E, Sedgwick TW, et al: In-home mental health services for the elderly. Clinical Gerontologist 27:71-85, 2004Google Scholar

10. Roane DM, Teusink JP, Wortham JA: Home visits in geropsychiatry fellowship training. Gerontologist 42:109-113, 2002Google Scholar