Brief Reports: Use of Emergency Department Services for Somatic Reasons by People With Serious Mental Illness

Although emergency department services are essential to the continuum of care for somatic health problems, overuse of the emergency department for nonurgent medical problems may cause increased costs and adverse health outcomes. According to the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey ( 1 ), in 2002 there were 110.2 million emergency department visits (39.8 per 100 persons) in the United States, 28.7 percent of which were semiurgent or nonurgent. Other work indicates rates of emergency department use in excess of 80 percent for nonurgent problems ( 2 ).

Although extensive emergency department use for medical problems has been documented among vulnerable populations—including the elderly ( 3 ), children ( 4 ), and homeless persons ( 5 )—little is known about such emergency department use by people with serious mental illness. Factors increasing emergency department use among other vulnerable groups and the general population include specific medical conditions and chronic medical problems ( 6 , 7 ), injury and victimization ( 5 ), self-rated poor health status ( 6 , 7 ), frequent use of other health care services ( 8 ), inadequate or inaccessible primary care ( 4 , 5 ), and Medicaid or lack of insurance ( 9 ). The relevance of these factors among people with serious mental illness remains unknown.

Increased rates of medical disease and premature death among people with serious mental illness underscore the importance of reducing this knowledge gap ( 10 , 11 ). Prior studies have shown that patients with serious mental illness were less likely than the general population to receive specialized cardiac procedures ( 12 ) and outpatient preventive care services ( 13 , 14 ). However, other studies have demonstrated that individuals with serious mental illness were more likely than their peers without mental illness to use some medical care services ( 15 ). We previously reported that 191 individuals with serious mental illness were more likely than a matched group of 3,052 from the general population to use the emergency department for medical problems (37 percent compared with 20 percent; p<.001) and to report seeing a primary care physician, although the rates of medical hospitalization did not differ ( 15 ). Psychiatric patients in that study reported more barriers to receiving care than those without a mental illness ( 15 ).

Because of the increased rates of co-occurring medical conditions found among adults with serious mental illness ( 10 , 11 ), the fact that care in the emergency department can cost between 50 and 100 percent more than comparable care in a physician's office ( 16 ) with reduced quality of care ( 4 ) and because of the high rate of emergency department use among adults with serious mental illness in our previous report ( 15 ), we aimed to identify the correlates of emergency department use for medical problems in this vulnerable population.

Methods

Data were drawn from a larger study of comorbid somatic conditions and service use that employed a cross-sectional design to survey a random stratified sample of 200 adults with a diagnosis of serious mental illness who received community-based outpatient psychiatric services. The survey, which has been previously described ( 15 ), includes items drawn from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) ( 17 ). Interviews were conducted between March and December 2000. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at the two study sites.

By design, half the sample had a diagnosis of schizophrenia; the other half had a diagnosis of a major mood disorder. Half the patients came from an urban site at the University of Maryland, and half were from a suburban site at Sheppard Pratt Hospital Systems.

First, we tested unadjusted bivariate associations between emergency department use and several person-level variables (gender, race, education, diagnosis, recruitment site, measures of comorbid medical conditions, and measures of health behavior) and service-level variables (usual source of medical care, provider changes, and mental health services). Chi square tests were used in these analyses. Variables significantly associated with emergency department use (p<.05) were then included in an adjusted multiple logistic regression model along with gender, age, race, site, and psychiatric diagnosis. From this model, adjusted odds ratios, 95 percent confidence intervals, and p values were computed. Because of the colinearity between the number of comorbid conditions and the indicator variables for any or specific comorbid conditions, we included only "any comorbid conditions" in the regression model.

Results

A total of 200 participants were in our sample. The mean±SD age was 44.0± 8.9 years. A total of 105 participants (53 percent) were female. A total of 112 (56 percent) were white, 71 (36 percent) were African American, six (3 percent) were Asian American, and 11 (6 percent) self-identified as "other." The mean number of years of education was 12.7±3.0.

In our sample, 74 patients (37 percent) reported going to the emergency department for somatic reasons in the past year. Of these 74 patients, 44 (22 percent) made a single visit, 21 (11 percent) made two or three visits, and nine (5 percent) reported four to nine visits.

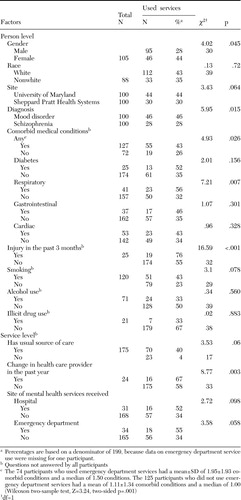

Bivariate analyses are presented in Table 1 . Participants were asked about 24 different comorbid medical conditions, and the most frequently reported categories of medical problems were included in the bivariate analysis. Chi square tests indicate that being female and having a mood disorder (compared with schizophrenia) were significantly associated with emergency department use. Presence of any comorbid somatic condition was also significantly related to emergency department use, as were injury in the past three months and respiratory illness. Participants who reported emergency department use had, on average, more comorbid medical conditions than those who did not report use (1.95±1.93 conditions compared with 1.11±1.34 conditions; t=3.28, df=115, p=.001). Past-year change in health care provider was the only service-level variable significantly related to emergency department use.

|

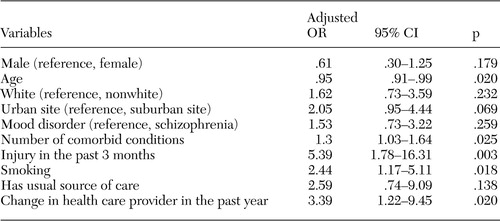

Table 2 shows adjusted odds ratio estimates for demographic variables and significant variables in the bivariate analysis. Smoking and usual source of care were also included in the analysis because they approached significance and were variables of interest. Person-level variables associated with use included age (older individuals were less likely to report use), greater number of comorbid somatic conditions, injury in the past three months, and smoking. The only service-level variable significantly associated with emergency department use was change in health care provider in the past year.

|

Discussion

As reported in our earlier investigation ( 15 ), patients in our psychiatric sample had higher rates of emergency department use than the general population (37 percent compared with 20 percent). They also had higher use of somatic outpatient services than the comparison national sample (80 percent compared with 65 percent) but had comparable rates of somatic hospitalization (13 percent compared with 9 percent). This high level of emergency and general outpatient medical service use may reflect higher rates of comorbid somatic conditions in the psychiatric sample ( 12 ). Although we could not determine the severity of these illnesses, the findings may reflect the increased need for medical care as a result of more serious medical conditions. The high rates of emergency department use combined with the use of outpatient care that was reported by 80 percent of the sample may also reflect elevated need for more regular medical care.

However, the lack of a comparable excess number of somatic medical hospitalizations (expected to covary with medical need) suggests several alternative explanations for the high utilization rates reported. It is conceivable that patients with severe mental illness overuse emergency department services. However, it is also possible that the patient group had more medical emergencies that were appropriately addressed in this setting. This theory is supported by the increased numbers of injuries in the psychiatric sample. Perceived barriers to care may be another reason. We previously reported that 59 percent of the psychiatric sample experienced at least one barrier to receiving medical care, such as waiting too long for an appointment, compared with only 19 percent of a national sample ( 15 ). Individuals in our study may have needed to make more acute and nonacute ambulatory visits to successfully obtain medical care. It is also possible that persons who seek medical care relatively frequently have increased opportunities to be exposed to the variety of barriers associated with gaining access to high-quality care ( 15 ).

Change in health care provider was the only service-level variable correlated with emergency department use and may represent another perceived barrier to care. This finding underscores the need for a consistent, accessible source of somatic care for people with mental illness.

The association of injury with emergency department use is consistent with findings from the general population, in which injury accounted for a higher proportion of medical expenditures than any other single condition ( 18 ). The association between smoking and emergency department use is consistent with our previous work that indicated an association between smoking and emphysema in our study population ( 11 ). One study ( 19 ) found pulmonary illness to be the most frequently occurring comorbid condition (31 percent) among 147 persons with serious mental illness. Furthermore, our previous work found higher rates of chronic pulmonary disease among people with serious mental illness compared with the general population, even after the analysis controlled for smoking.

The fact that drug and alcohol use were not correlated with emergency department use is somewhat surprising. This finding may be related to the relatively low rate of substance use reported in the study population, a phenomenon that likely arose from our sampling strategy and potential underreporting.

Age was negatively associated with emergency department use. This finding is consistent with an earlier study that suggested that elderly individuals use emergency department services more appropriately than younger patients ( 3 ). It may be that older individuals with multiple medical issues are more likely to be engaged in consistent health care and thus less likely to use the emergency department for nonurgent problems.

Some limitations of our study, including the use of self-report data, have been addressed in our previous report ( 15 ). The lack of a specific question about reasons for each emergency department visit is another limitation, although we ensured that patients understood that questions referred to use of the emergency department for somatic rather than psychiatric problems. Also, we did not review emergency department records. Because of the multiple determinants of health care use, there may be other variables for which we did not control that affected our dependent measures. For example, we did not directly evaluate the role of health insurance; more than 90 percent of persons treated at the study centers have Medicaid or Medicare. Furthermore, our findings are limited to individuals with serious mental illness who are actively engaged in mental health services.

This study raises issues about the relatively high use of somatic emergency department services, as well as routine outpatient somatic care, by people with serious mental illness. In addressing use of the emergency department for nonurgent problems in the general population, recommendations include optimizing the relationship between the patient and the primary care provider ( 20 ), having the primary care provider offer educational interventions ( 3 ), and establishing 24-hour primary care clinics ( 2 ).

Conclusions

Future work should focus on further assessing reasons for the relatively high use of emergency department services by people with serious mental illness. Continued efforts to integrate, or at a minimum better coordinate, somatic and mental health services might also decrease use of nonurgent emergency department services and optimize use of less acute somatic care.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant from the National Association for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (Dixon, principal investigator).

1. National Center for Health Statistics: National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Hyattsville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2004Google Scholar

2. Ehrlich NJ, Tasmin F, Safe H, et al: Pilot study of ER utilization at Tulsa hospitals. Journal of the Oklahoma State Medical Association 97:64-68, 2004Google Scholar

3. Parboosingh EJ, Larsen DE: Factors influencing frequency and appropriateness of utilization of the emergency room by the elderly. Medical Care 25:1139-1147, 1987Google Scholar

4. Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine: Overcrowding in our nation's emergency departments: is our safety net unraveling? Pediatrics 114:878-888, 2004Google Scholar

5. Padgett DK, Struening EL, Andrews H, et al: Predictors of emergency room use by homeless adults in New York City: the influence of predisposing, enabling, and need factors. Social Science and Medicine 41:547-556, 1995Google Scholar

6. Ginsberg G, Israeli A, Cohen A, et al: Factors predicting emergency room utilization in a 70 year old population. Israeli Journal of Medical Science 32:649-664, 1996Google Scholar

7. Chou KL, Chi I: Factors associated with the use of publicly funded services by Hong Kong Chinese or older adults. Social Science and Medicine 58:1025-1035, 2004Google Scholar

8. Hansagi H, Olson M, Sjoberg S, et al: Frequent use of hospital emergency department is indicative of high use of other health care services. Annals of Emergency Medicine 37:561-567, 2001Google Scholar

9. Fields WW, Asplin BR, Larkin GL, et al: The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act as a federal health care safety net program. Academic Emergency Medicine 8:1064-1069, 2001Google Scholar

10. Harris EC, Barraclough B: Excess mortality of mental disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 173:11-53, 1998Google Scholar

11. Sokal J, Messias E, Dickerson FB, et al: Comorbidity of medical illnesses among adults with serious mental illness who are receiving community psychiatric services. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 192:421-427, 2004Google Scholar

12. Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al: Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA 283:506-511, 2000Google Scholar

13. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, et al: Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Medical Care 40:129-136, 2002Google Scholar

14. Salsberry PJ, Chipps E, Kennedy C: Use of general medical services among Medicaid patients with severe and persistent mental illness. Psychiatric Services 56:458-462, 2005Google Scholar

15. Dickerson FB, McNary SW, Brown CH, et al: Somatic healthcare utilization among adults with serious mental illness who are receiving community psychiatric services. Medical Care 41:560-570, 2003Google Scholar

16. Krugg SE: Access and use of emergency services: inappropriate use versus unmet need. Clinical Pediatric Emergency Medicine 1:35-44, 1999Google Scholar

17. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Hyattsville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics, 1998Google Scholar

18. Ray GT, Collin F, Lieu T, et al: The cost of health conditions in a health maintenance organization. Medical Care Research and Review 57:92-109, 2000Google Scholar

19. Jones DR, Macias C, Barreira PJ, et al: Prevalence, severity, and co-occurrence of chronic physical health problems of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:1250-1257, 2004Google Scholar

20. Stein AT, Harzheim E, Costa M, et al: The relevance of continuity of care: a solution for the chaos in emergency services. Family Practice 18:207-210, 2002Google Scholar