Special Section on Seclusion and Restraint: Consumers' Perceptions of Negative Experiences and "Sanctuary Harm" in Psychiatric Settings

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Recent studies show a high prevalence of trauma symptoms among people with serious mental illness who are treated in public-sector mental health systems. Unfortunately, growing evidence suggests that many consumers have had traumatic or harmful experiences while being treated in various psychiatric settings. This study explores consumers' perceptions of such harmful inpatient experiences, events that the authors place under the rubric of "sanctuary harm." METHODS: The authors conducted semistructured qualitative interviews with 27 randomly selected mental health consumers to hear their descriptions of adverse events that they experienced while receiving psychiatric care. Our analysis of interview transcriptions focused on understanding consumers' narratives of harmful experiences—events that would not meet DSM-IV criteria for trauma but that nevertheless resulted in significant distress. RESULTS: Eighteen of 27 interviewees described harmful incidents that they had witnessed or experienced directly, many of which evoked strong emotional responses by consumers during their narration. Nearly all incidents described were hospital based and were clustered around two sets of themes. The first set related to the hospital setting, including the fear of physical violence and the arbitrary nature of the rules. The second set related to the narrators' interactions with clinical staff, including depersonalization, lack of fairness, and disrespect. CONCLUSIONS: The findings suggest that many mental health consumers have had a lifetime sanctuary experience that they perceived as harmful. They also offered suggestions for how the mental health service delivery system might reduce the potential for sanctuary harm experiences.

Recent studies indicate that trauma victimization and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are highly prevalent among people with serious mental illness who are treated in the public sector (1,2). Nevertheless, trauma-specific services are rarely available to these mental health consumers. The South Carolina Department of Mental Health (SCDMH), along with mental health departments from several other states, has initiated formal efforts to address the needs of trauma victims in response to the concerns of its mental health consumers (3). One of the priority areas that were identified by consumers within the SCDMH initiative is examining the safety and dignity of psychiatric settings, including consumers' perceptions of traumatic or harmful events that occur within those settings.

Our conceptual framework is based on our distinction between traumatic and harmful events that occur within the sanctuary of the psychiatric setting (4,5; personal communication, Cousins VC, 2005). Sanctuary trauma refers only to those incidents in psychiatric settings that meet the DSM-IV criteria for a traumatic event—that is, the person experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with an event or events that involved actual or threatened death or serious injury or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others, and the person's response involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror (6). In the companion article in this issue (9) we present quantitative data on 142 persons with severe mental illness and a history of psychiatric hospitalization and found that many of them met the criteria for sanctuary trauma: 9 percent were sexually assaulted, 31 percent were physically assaulted, and 63 percent witnessed trauma. Sanctuary harm applies to events in psychiatric settings that do not meet the formal criteria for trauma but that involve insensitive, inappropriate, neglectful, or abusive actions by staff or associated authority figures and invoke in consumers a response of fear, helplessness, distress, humiliation, or loss of trust in psychiatric staff. In the quantitative companion article published in this issue (9), many study participants met the criteria for sanctuary harm: 65 percent were transported in handcuffs, 60 percent had been put in seclusion, and 34 percent had been restrained.

A national study of the general adult population found that up to 56 percent had experienced DSM-IV trauma and 8 percent had experienced PTSD (7). Among adults with a serious mental illness, up to 98 percent had experienced a DSM-IV trauma and 42 percent had experienced PTSD (8). A DSM-IV trauma can cause depression, impaired functional status, comorbid medical conditions, and an increased use of medical services. It is unknown what outcomes are caused by sanctuary trauma, but we hypothesized that it could lead to the exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms and reduced participation in psychiatric care. It is also unknown what outcomes are caused by sanctuary harm, but we hypothesized that it could lead to reduced self-esteem and sense of self-worth, exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms, and reduced participation in psychiatric care.

The purpose of this qualitative study was to enhance our understanding of consumers' perceptions of sanctuary harm. We attempted to establish a foundation for learning if harmful experiences result in new or exacerbated psychiatric symptoms, a difficult recovery process, or reduced participation in subsequent mental health treatment. We offer several caveats. First, this focus on harm events is not intended to minimize the impact of sanctuary trauma but instead to underscore the emotional and long-term significance of events that might go unnoticed in the clinical community. Second, we do not view psychiatric settings as "snake pits"—the clinical services provided by such facilities have benefited a great number of mental health consumers and will continue to do so. Rather, we aim to elucidate a phenomenon much talked about in consumer circles but inadequately addressed by the research community. Third, these narratives represent the perspectives of only one group of participants; staff members' accounts of these or similar events were not the focus of this study. Nevertheless, because consumers have lacked a voice for their experiences, we focus on consumers' accounts of perceived harmful events and their perspectives on how challenging situations in psychiatric settings might be handled in a safer, more dignified manner.

Methods

Setting and participants

As part of a larger study on patient safety in psychiatric settings conducted from 2002 to 2004 (9), participants were recruited from a day hospital program in an SCDMH-affiliated community mental health center in Charleston, South Carolina. Consumers in this program had been given a diagnosis of a serious mental illness, many had been hospitalized numerous times, and most required support with activities of daily living. Eligibility criteria for the study were a previous history of psychiatric hospitalization and the ability to understand the study procedures and give informed consent. Consumers were not excluded on the basis of psychiatric diagnosis. A computer-generated simple random sampling procedure was used to randomly select potential participants from a current client list, which was periodically updated with new admissions.

Although quantitative data were collected for the entire sample, we randomly selected 20 percent of the sample to conduct individual thematic interviews. Although there is no statistical standard for selecting the right number of interviewees for a qualitative study, particularly when trying to learn about the prevalence of subjective experiences, we believed that randomly selecting one-fifth of the overall sample would provide a reasonable basis for our research aims. Furthermore, 20 percent of the total sample was a feasible number of interviews to conduct, transcribe, and analyze during the study period.

The first author and the study team developed a semistructured interview guide (10) that encouraged participants to describe events that they found to be distressing but that we might not have considered to be traumatic or harmful. For example, participants were asked to describe any events that they experienced or witnessed within a psychiatric setting that they believed to be unsafe or frightening, their perceptions of what happened and why, and any consequences of those experiences. The protocol also included probes to elicit greater narrative detail about individuals' descriptions of events, including, "How might the situation have been handled differently?" A copy of this protocol can be obtained from the first author.

The first author conducted a two-day training session with the study team in Charleston, which included a half-day discussion on the epistemologic framework for the interviews, and a review of and opportunity to practice the protocol. The first author also supervised and reviewed the first two interviews for the two team members who conducted all the qualitative interviews. Throughout the course of the study, team members communicated regularly to review our initial research questions and provide feedback to the interview team. All interviews were recorded with the participants' consent, and the tapes were subsequently transcribed.

This study was conducted with full approval of the institutional review boards of the Medical University of South Carolina and the SCDMH and was in full compliance with requirements concerning human subjects. Interviewees received one $25 payment for study participation.

Qualitative analysis and interpretation

Copies of the interview transcriptions were compared with the audiotapes to correct any errors or omissions. Each author conducted multiple readings of the transcripts to identify recurrent themes in the participants' stories. These themes were further developed and organized by the first author and then reviewed and edited by the others. The authors then met to discuss the issues that emerged from our readings, resolve questions, and refine the thematic categories.

Results

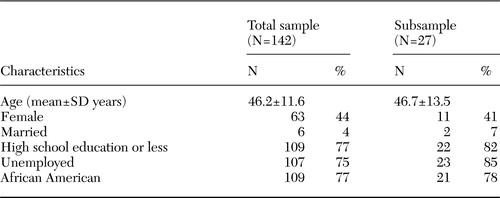

Of the 156 consumers eligible for our study, 142 (91 percent) provided consent and completed the quantitative study procedures. We conducted individual thematic interviews with a randomly selected subsample of 27 participants (20 percent). As shown in Table 1, the demographic characteristics of this subsample parallel those of the larger sample and are generally representative of the program's clientele. Eighteen persons in the subsample recounted at least one perceived adverse hospital experience in their lifetime.

Reviews of the transcripts revealed that most incidents described by consumers were hospital based and were concentrated around two sets of themes. The first related to the psychiatric hospital setting and included the threat of physical violence and the arbitrary nature of "the rules." The second set of themes dealt more directly with consumers' interactions with clinical staff and included staff members' not knowing the consumers as individuals, a perceived lack of fairness, and consumers' experiencing disrespect or embarrassment in the hospital.

Hospital setting

Threat of physical violence. Many consumers, even those who had not experienced a physical assault, said that the hospital felt inherently unsafe. Some respondents talked about the combustible mix of clients on the unit; others spoke about potentially violent staff members.

B: "I used to call it the Goon Squad, right. They would be staff members who came to, I guess, quiet down patients … they beat the patients to the floor and put their foot on the dude's neck and held his arm and held him to the floor and then threw him in seclusion. So I was afraid of them."

A: "Because [a staff member] was, like, a little short guy and real heavy, and he used to be built and stuff. And all of them [consumers] was afraid, because they told me when I first came there, 'That's the one you better watch out for, that one right there.'"

These descriptions are representative of accounts we heard from numerous respondents, suggesting that inpatient settings are often perceived as volatile, threatening environments.

The rules. Rules and regulations historically have been key components of psychiatric care (11,12). Respondents described various regulations that they encountered in psychiatric hospitals and their confusion over the perceived arbitrary enactment of these rules.

C: "[The hospital] had paper pajamas. And they are not something you want to sleep in. They itch like crazy. So I tore mine off and put my own pajamas on, so they had me sleep in the hallway. It's like, just because I switched from something that's irritating my skin to something that will not, they stick you in the hall …. It didn't make no sense."

D: "You can't get no cigarettes from another floor. You got to get all your cigarettes from somebody on the fourth floor [the floor D was on] … or none at all. If [consumers] come from the third floor, [they] can't get nothing from the fourth floor; fourth floor can't get nothing from the third floor."

"Consistency" and "structure" are oft-heard refrains in clinical training. However, in practice rules may become arbitrary and their enforcement capricious (13). Such contradictions between theory and practice were not lost on respondents, who generally acknowledged that despite their need for treatment, the rote enactment of "order" did not seem very efficacious. In one instance, it simply afforded the respondent the means for an early discharge.

C: "Half the time I sit there, and I'll play the game and get out early. I had to do that in Massachusetts, play the game, and I was, I was so darned good at it that they believe it."

Interviewer: "And what result does that have?"

C: "Well at the time when you want to get out, and you know that you need to get out because you're not getting what you need, and they won't let you out until they hear certain things."

Interactions with clinical staff

Not knowing consumers as individuals. The tendency for "total institutions" to remove all traces of individuality is perhaps anticipated by those who voluntarily join the military or a fraternity (14). Yet study participants—often involuntarily committed—appear to have been taken aback by the impersonal treatment that they received in the hospital, particularly because of the emphasis on individualized treatment plans to address the idiosyncratic symptoms of consumers' illnesses. As has been documented elsewhere (15), being seen as "just another consumer" proved distressing for many interviewees.

G: "Sometimes certain people [other consumers] would be bothering me, and I wouldn't want to be bothered and whatever. I was trying to tell them, 'Leave me alone,' and then I think the staff would think I was trying to cause them trouble, and they would consequent me sometimes versus consequent the person who was actually starting everything, 'cause sometimes, as life goes, some people don't come in … on the beginning and come in on the tail end of certain things, and they go by what they're seeing, not what was actually going on."

Lack of fairness. Interviewees often talked about "unfair" treatment, particularly about the use of seclusion and restraints or crisis intervention teams. However, in many of the descriptions, individuals' distress appeared to be related not to the experience of seclusion itself but instead to the process leading to seclusion, which by several accounts had no reasonable explanation:

I: "Nothing didn't happen, but you know, I was locked up …. I mean, I didn't talk or doing nothing, and I was locked up."

J: "I was at [the hospital]. I was put in there. Yeah, I was tied down because my aunt say I was very sick. They let me stay there overnight with no blanket or nothing. That room in there was so cold. I was crying like a baby."

Interviewer: "Did they have someone there with you?"

J: "Someone come in and check on me …. I was thinking they were wrong … and they turn off the lights …. I was scared, you know, and I was crying … I was wondering why they did that to me."

Interviewer: "How did you feel about being in seclusion? What was that like for you?"

B: "It was scary [consumer's lip trembles] … because I get claustrophobic and everything. And the only thing that saved me was one of the patients was playing the piano, and the seclusion room wasn't that far from the piano."

Interviewer: "Why did they put you in seclusion?"

B: "I don't know. I don't know."

Disrespect and humiliation. Finally, participants described interactions with staff that they perceived to be disrespectful, unwarranted, and, in some instances, humiliating.

K: "I remember one morning, I woke up and I laid there, but they wanted us to get out of bed real early that morning …. I didn't see nothing wrong with it. I didn't want to be bothered. I wanted to sleep. And one or two of those nurses throwed some cold water on me, and then I got up!"

L: "When they put me in there, the nurse came to me, and I forgot what she wrote or told me. She was coughing; she had a cold. And the food came in on the cart, and [I] said, 'You coughing; don't cough over the food.' And she tried to do it again, you know, to show it off, you know. So I don't know. I said, 'I don't want the food; you can have it.' I kept acting up, so we start fighting."

M: "And so about three or four of them jump on me, and they put me in a straitjacket, and they put me in the room, and then they put me in a sheet. That's something that covers your whole body with the straightjacket on. They clamp it down to the mattress, to the springs. Clamped it down, you know, on the edges, clamp that down over across your waist …. The only thing that be out is your toes or your feet and your head."

Interviewer: "So you're totally restrained?"

M: "Totally. And I was, whatever you got to do, you do it right there. If you got to use the bathroom, you got to urinate, got to [inaudible] your bowels, you do it right there. It just happened so I did urinate in my clothes, but I didn't, I wasn't, I didn't have to pass no … pass the waste. I didn't have to do that."

Interviewer: "How long [were you restrained for]?"

M: "Twenty-four hours."

A: "I'd like to see them be treated like human beings like everybody else. They all ain't that crazy, you know, and they all wouldn't want to hurt nobody. I want to see them [staff] treat them [consumers] like out here in the community and stuff like that …. They didn't ask to go there. Maybe some of them needed help, but they need the right kind of help, not the wrong one."

Discussion

In this randomly selected sample of 27 participants, 18 recounted at least one perceived adverse hospital experience in their lifetime. Moreover, many of the incidents took place not in South Carolina but throughout the country. Sanctuary harm events thus do not appear to be idiosyncratic to South Carolina's public mental health system but are more widespread, suggesting that some of our most ill and vulnerable citizens—our family members, our neighbors, ourselves—are leaving treatment facilities feeling embarrassed, uncared for, and unsafe.

But how accurate are these accounts? In previous studies of consumers' experiences with seclusion and restraint, for example, interviews occurred no more than one week after the event (16,17,18). Our study asked consumers about lifetime experiences. Research on the reliability of autobiographical memory is equivocal (19,20), although some studies suggest that long-term recall for unique (21) or salient (22) events can be quite good. And although some interviewees in our study had trouble recalling specific events, we have no reason to discount any participants' emotionally resonant descriptions of their experiences. Indeed, as Anthony (23) notes, "Recovery from mental illness involves much more than recovery from the illness itself. People with mental illness may have to recover from the stigma they have incorporated into their very being; [and] from the iatrogenic effects of treatment settings." The findings reported here support ongoing efforts to reduce the incidence of traumatic and harmful events in psychiatric settings (24), which may result in long-lasting emotional distress and distrust of the formal treatment system.

However, negative experiences should not be an inevitable result of psychiatric care. Our participants were concerned about some of the potentially harmful events that they had experienced and witnessed, and, in fact, made recommendations for possible changes to improve consumers' experiences, including revising hiring practices.

N: "Some people don't be fit for a certain type of job …. You can't pick a person like that, impatient, because I think he would do more harm to the patient than helping them."

Other participants also stated that staff should learn to be more sensitive to consumers.

O: "I think patients should actually be listened to rather than in one ear and out the other and case closed. I guess with all the patients, clients, they [staff] don't have that much time, and so, to be able to do that. But when you're a patient, that's what you need."

Changes to policies and procedures consistent with these recommendations may alleviate some of the problems described by interviewees.

One limitation of this study is that we did not interview staff for their perspectives on these or similar incidents. Others have suggested that staff often view use of seclusion and restraint not as punishment but as protection of distressed consumers from harm (16). Future research by this team will explore staff members' perceptions not simply of seclusion and restraint events but also of daily interactions that consumers have described as "disrespectful" or otherwise "harmful." Such research may contribute to constructive dialogue about maintaining consumers' safety, while still respecting their dignity as individuals.

Conclusions

This work represents an early step toward understanding psychiatric care events that mental health consumers perceive to be harmful and the long-term consequences of such experiences. Our initial findings suggest that many consumers have experienced events that resulted in no physical harm but that were perceived to be humiliating, dehumanizing (25), unreasonable, or distressing. Such events too often have gone unnoticed in research about psychiatric treatment. We hope that by highlighting consumers' perspectives on these incidents we can call attention to the "little things" that may, in fact, have a long-term emotional impact on consumers and their willingness to participate in follow-up services. Understanding how adverse sanctuary events are understood and experienced by both consumers and staff may help us to determine what steps can be taken to ensure the provision of safe, humane, and dignified psychiatric care.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by grants MH-01660 and MH-65517 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Robins is affiliated with Westat in Rockville, Maryland. Ms. Sauvageot, Dr. Suffoletta-Maierle, and Dr. Frueh are with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Dr. Frueh is also with the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Charleston. Dr. Cusack is with the South Carolina Department of Mental Health in Charleston. Send correspondence to Dr. Frueh at the Medical University of South Carolina, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 67 President Street, P.O. Box 250861, Charleston, South Carolina 29425 (e-mail, [email protected]). This article is part of a special section on the use of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric treatment settings.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of consumers of a day hospital program in a community mental health center

1. Cusack KJ, Frueh BC, Brady KT: Trauma history screening in a community mental health center. Psychiatric Services 55:157–162,2004Link, Google Scholar

2. Cusack KJ, Frueh BC, Hiers TG, et al: Trauma within the psychiatric setting: a preliminary empirical report. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 30:453–460,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Frueh BC, Cusack KJ, Hiers TG, et al: Improving public mental health services for trauma victims in South Carolina. Psychiatric Services 52:812–814,2001Link, Google Scholar

4. Bloom S: Creating sanctuary: Towards the Evolution of Sane Societies. London, Routledge, 1997Google Scholar

5. Frueh BC, Dalton ME, Johnson MR, et al: Trauma within the psychiatric setting: conceptual framework, research directions, and policy implications. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 28:147–154,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1999Google Scholar

7. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the national comorbidity study. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:1048–1060,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Mueser K, Goodman LA, Trumbetta SL, et al: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:493–499,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Frueh BC, Knapp RG, Cusack KJ, et al: Patients' reports of traumatic or harmful experiences within the psychiatric setting. Psychiatric Services 56:1123–1133,2005Link, Google Scholar

10. Bernard HR: Unstructured and semi-structured interviewing, in Research Methods in Anthropology. Walnut Creek, Calif, Alta-Mira Press, 1995Google Scholar

11. Foucault M: Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York, Pantheon, 1977Google Scholar

12. Rothman DJ: The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic. Boston, Little, Brown, and Company, 1971Google Scholar

13. Kesey K: One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. New York, Penguin Books, 1962Google Scholar

14. Goffman E: Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates. Garden City, Anchor Books, 1961Google Scholar

15. Crossley ML, Crossley ML: "Patient" voices, social movements, and the habitus: how psychiatric survivors "speak out." Social Science and Medicine 52:1477–1489,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Outlaw FH, Lowery BJ: An attributional study of seclusion and restraint of psychiatric patients. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 8:69–77,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Sheridan M, Henrion R, Robinson L, et al: Precipitants of violence in a psychiatric inpatient setting. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:776–780,1990Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Binder RL, McCoy SM: A Study of patients' attitudes toward placement in seclusion. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:1052–1054,1983Abstract, Google Scholar

19. Neugebauer R: Reliability of life-event interviews with outpatient schizophrenics. Archives of General Psychiatry 40:378–383,1982Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Barsky AJ: Forgetting, fabricating, and telescoping: the instability of the medical history. Archives of Internal Medicine 162:981–984,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Allen JG: The spectrum of accuracy in memories of childhood trauma. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 3:84–95,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Maughan B, Rutter M: Retrospective reporting of childhood adversity: issues in assessing long-term recall. Journal of Personality Disorders 11:13–33,1997Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Anthony W: Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:11–23,1993Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Jennings A, Ralph RO: In Their Own Words: Trauma Survivors and Professionals They Trust Tell What Hurts, What Helps, and What Is Needed for Trauma Services. Maine Trauma Advisory Group, 1997Google Scholar

25. Barnett S, Silverman MG: Ideology and Everyday Life: Anthropology, Neomarxist Thought and the Problem of Ideology and the Social Whole. Chicago, University of Michigan Press, 1979Google Scholar