Special Section on Seclusion and Restraint: Patients' Reports of Traumatic or Harmful Experiences Within the Psychiatric Setting

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the frequency and associated distress of potentially traumatic or harmful experiences occurring within psychiatric settings among persons with severe mental illness who were served by a public-sector mental health system. METHODS: Participants were 142 randomly selected adult psychiatric patients who were recruited through a day hospital program. Participants completed a battery of self-report measures to assess traumatic and harmful events that occurred during the course of their mental health care, lifetime trauma exposure, and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder. RESULTS: Data revealed high rates of reported lifetime trauma that occurred within psychiatric settings, including physical assault (31 percent), sexual assault (8 percent), and witnessing traumatic events (63 percent). The reported rates of potentially harmful experiences, such as being around frightening or violent patients (54 percent), were also high. Finally, reported rates of institutional measures of last resort, such as seclusion (59 percent), restraint (34 percent), takedowns (29 percent), and handcuffed transport (65 percent), were also high. Having medications used as a threat or punishment, unwanted sexual advances in a psychiatric setting, inadequate privacy, and sexual assault by a staff member were associated with a history of exposure to sexual assault as an adult. CONCLUSIONS: Findings suggest that traumatic and harmful experiences within psychiatric settings warrant increased attention.

Large studies of up to 500 persons with severe mental illness who are served within public-sector mental health clinics have shown high prevalence rates of trauma victimization (51 to 98 percent) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (up to 43 percent) (1,2). Persons with severe mental illness may also be vulnerable to additional traumatic or iatrogenic experiences that occur within psychiatric settings (3,4). For example, use of control procedures, such as seclusion and restraint, may recapitulate previous traumatic experiences and thereby exacerbate symptoms of PTSD or other mental illness. National mental health organizations, such as the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, have expressed concern about this issue (5), and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has released regulations encouraging limited use of seclusion and restraint (6). Furthermore, state trauma initiatives in South Carolina, New Hampshire, and other states have identified trauma and harmful practices within psychiatric settings as issues requiring further research and attention by state mental health systems (7).

Currently, efforts are under way to reduce the incidence of measures of last resort that are used to manage disruptive behavior on inpatient psychiatric units. The target of these efforts has been seclusion and restraint, focused primarily on patient and staff safety, staff training, and legislation (8,9,10,11). Some have suggested that routine clinical procedures on inpatient units may, because of the associated loss of control, represent a highly distressing experience for patients (12,13,14,15). Evidence indicates that psychiatric patients in the emergency department prefer psychotropic medication (64 percent) to seclusion or restraint (36 percent) (16). Another study found that although psychiatric nurses rated restraint as appropriate in 98 percent of cases, patients perceived it as being necessary in only 35 percent of the cases (17). Also, although patients' perceptions of the necessity for involuntary commitment change from the time of commitment to follow-up, negative perceptions of seclusion and restraint are stable across time (N=433) (18).

Unfortunately for policy efforts, few broad empirical studies have examined traumatic experiences and harmful practices that occur within psychiatric settings (4). Several studies have found that psychotic symptoms and involuntary commitment appear to be associated with PTSD (19,20,21). Other data have indicated that most posttreatment PTSD symptoms are related to psychotic symptoms rather than to actual treatment experiences, suggesting that psychotic symptoms are more traumatic than measures used to control them (12).

Other studies provide insight into patients' perceptions about aggression in psychiatric settings. Results of a study of female patients indicated that most (85 percent) with a history of abuse reported feeling unsafe in mixed-gender units (22). A study of patients found that 57 percent had witnessed aggression on a psychiatric unit during their lifetime (23). The results of another study suggested differences between patient and staff perceptions, with staff being more likely than patients to attribute incidents of aggression to patient illness and to view changes in medication as appropriate; patients requested improved staff-patient communication and more flexible unit rules (24). Recent research has suggested that high lifetime rates of traumatic and potentially harmful experiences occur within psychiatric settings (25). Although these studies suggest that the experience of psychiatric hospitalization may be distressing, harmful, or traumatic to some patients, they have methodologic limitations and are narrowly focused. Furthermore, with one exception (18), the samples were small, ranging from 19 to 100.

Empirical data are lacking for events that occur in psychiatric settings and meet DSM-IV (26) criteria for a traumatic event (sanctuary trauma) (4,27,28). Empirical data are also lacking for events that, although they do not meet DSM-IV criteria for trauma, involve insensitive, inappropriate, neglectful, or abusive actions by mental health staff or authorities and invoke among patients a response of fear, helplessness, distress, humiliation, or loss of trust in staff (sanctuary harm) (4,28). In a companion paper in this issue of Psychiatric Services, we describe a cross-sectional study to evaluate the frequency and associated distress of potentially traumatic or harmful experiences that occurred in psychiatric settings in a sample of patients from the public mental health system (28). In this companion study we also examined the interrelationships of and subjective reactions to these experiences and the self-report ratings of subsequent involvement in psychiatric care.

Methods

Participants

Study participants were randomly selected adult patients who were voluntarily admitted to a day hospital program in Charleston affiliated with the South Carolina Department of Mental Health. The program serves more than 100 patients weekly and averages 11 new admissions per month. Patients served by the program have severe mental illness—typically schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depressive disorder—and require assistance with independent living, symptom management, and prevocational skills.

Inclusion criteria were a history of psychiatric hospitalization and the ability to competently give informed consent. This study was conducted from 2002 to 2004 and was approved by the institutional review boards of the Medical University of South Carolina and the South Carolina Department of Mental Health. All participants signed informed consent documents before study participation and were paid $25 for their participation.

Research procedures

Participants were randomly selected from a current program roster, which was periodically updated with new admissions. A computer-generated simple random sampling procedure was used. Project staff approached potential participants at their scheduled visits to obtain informed consent. Patients who did not show up for these scheduled appointments were contacted, and arrangements were made to reschedule if possible. All patients who consented to participate in the study completed a short battery of self-report measures, which took 60 to 90 minutes. Project staff read the self-report measures aloud to all participants to minimize literacy problems. Individual thematic interviews were also conducted with a subsample of patients and are reported separately (28).

Instruments

Psychiatric Experiences Questionnaire (PEQ). This instrument was designed for this project to assess for a wide range of traumatic and harmful experiences that may occur within psychiatric settings. Twenty-six items on the PEQ list possible experiences (for example, being strip-searched) and assess whether the event was experienced, the level of distress one week after the event, and the level of distress since the event. This measure was developed from focus groups conducted with patients from various areas of South Carolina, and it received preliminary testing and refinement in a pilot study (25). We also included additional items about general perceptions of personal safety, fear, helplessness, and distress. Scores on these items range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating less safety and more feelings of fear, helplessness, distress, and compliance. Compliance with psychiatric recommendations was also assessed by asking the participant, "In general, how well have you followed specific psychiatric recommendations (for example, medications and therapy)?" Scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more compliance.

Trauma Assessment for Adults-Self-Report Version (TAA). This 17-item instrument assesses for lifetime history of traumatic events (for example, sexual assault) and has been widely used in research on trauma exposure among adults (29). By surveying a sample of 23 adults in a local mental health population, the authors of the TAA found that it was easy to administer and that rates of trauma and crime exposure were consistent with rates previously found in the same population by using a different trauma assessment tool (29). Archival data from the mental health records of a subset of 15 patients revealed that the TAA detected all stressor events noted in the mental health records of these individuals and other stressor events that were not in the records. Recent data show that a history of PTSD and trauma has been reliably assessed by using similar measures among public-sector patients with severe mental illness (30,31).

PTSD Checklist (PCL). The PCL is a 17-item self-report measure of PTSD symptoms that is based on DSM-IV criteria (32). The checklist has a 5-point Likert scale response format. It has been found to be highly correlated with a structured interview for PTSD (r=.93), has good diagnostic efficiency (greater than .70), and has robust psychometric properties with a variety of trauma populations (33,34). Scores on the PCL range from 17 to 85, with scores of 50 or higher indicating that the patient has probable PTSD.

Statistical analyses

We conducted a series of analyses to describe the frequency of and distress associated with sanctuary harm and trauma events, including point and 95 percent confidence interval estimates of the proportion of patients who endorsed each individual item on the PEQ. We also conducted analyses to examine the proportions endorsing individual PEQ items by demographic variables, presence of probable PTSD, and lifetime trauma, as well as the associations between sanctuary harm and trauma items and perceptions of personal safety, helplessness, fear, distress, and compliance with psychiatric recommendations. These simple analyses of associations were carried out with either a chi square test or Fisher's exact test if indicated. Because we examined lifetime history of exposure to events, the potential confounding effect of age was adjusted for with odds ratios obtained from a logistic regression analysis. When examining the associations between sanctuary trauma and harm items and other variables, we implemented a Bonferroni correction for each set of analyses to reduce the possibility of familywise error, resulting in a new significance level of .0019 for sets with 26 variables.

Results

Participants

We initially approached 156 randomly identified patients, 142 of whom consented to participate, for a participation rate of 91 percent. Of the 14 patients who elected not to participate, eight cited no interest and four believed that participation would be too distressing. The mean±SD age of the participants was 46.2±11.6 years. Sixty-two (44 percent) were female, six (4 percent) were married, 109 (77 percent) had a high school education or less, 106 (75 percent) were unemployed, and one (1 percent) was working full-time. Thirty-two (23 percent) were white, and 109 (77 percent) were African American.

PEQ results by item and category for total sample

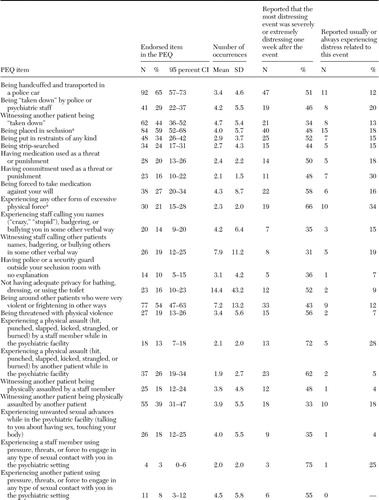

Individual item results for the PEQ are presented in Table 1. For example, among patients who reported handcuffed transport (92 respondents, or 65 percent), this event occurred a mean of 3.4±4.6 times, and 47 respondents (51 percent) reported a severe or extreme level of distress in the week after the most distressing occurrence of the event. Eighty-four patients were placed in seclusion, which occurred an average of 4.0±5.7 times. Forty of these patients (48 percent) indicated severe or extreme levels of distress in the week after the most distressing occurrence of the event. Among the least frequently endorsed events were sexual assault by another patient (8 percent) or by staff (3 percent) and witnessing a sexual assault by another patient (6 percent) or by staff (5 percent). Although these events were experienced by only a few patients, they were highly distressing. When combining the categories of assaults by other patients and assaults by staff, results show that 44 respondents (31 percent) reported at least one physical assault and 12 (8 percent) reported at least one sexual assault in a psychiatric setting. When the five items that pertain to the witnessing of an event were combined, results show that 90 (63 percent) reported witnessing at least one traumatic event.

PEQ results by demographic variables

A conservative Bonferroni correction was used (alpha=.0019), and the analyses found no statistical differences in the proportion of patients who reported traumatic or harmful psychiatric experiences by either gender or age (younger than 50 years compared with 50 years or older). Furthermore, only one significant difference was found in reports of traumatic or harmful experiences by race. Whites were significantly more likely than African Americans to report unwanted sexual advances in psychiatric settings (12 of 32 whites, or 38 percent, compared with 14 of 109 African Americans, or 13 percent; χ2=10.00, df=1, p<.001), a difference that held after the analyses adjusted for age.

Lifetime trauma exposure and current PTSD symptoms

General lifetime trauma exposure in the sample was high (123 respondents, or 87 percent), including physical assault (67 respondents, or 47 percent) and sexual assault (47 respondents, or 33 percent), with many reporting more than one type of lifetime trauma (68 respondents, or 48 percent). Current PTSD symptom levels were high, and 27 respondents (19 percent) met criteria for probable PTSD. Results demonstrated that the PCL was a reliable measure with this sample (Cronbach's coefficient alpha=.93).

PEQ results by TAA categories

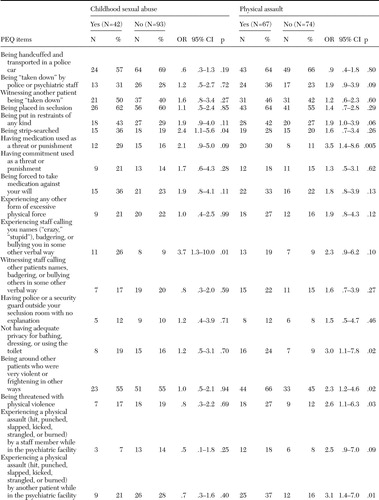

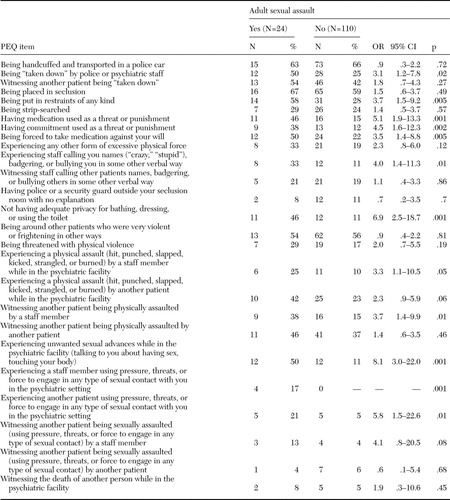

With the Bonferroni correction, the analyses showed no statistical differences in reports of traumatic or harmful psychiatric experiences by either childhood sexual abuse or physical assault (Table 2). However, the 24 patients who reported a lifetime history of sexual assault as an adult had significantly higher reported rates of several psychiatric traumatic or harmful experiences than the 110 patients who did not report such a history (Table 3). As shown in Table 3, compared with patients with no lifetime history of sexual assault as an adult, patients with such a history were more likely to report having medications used as a threat or punishment (46 percent compared with 15 percent; χ2=11.99, df=1, p<.001), unwanted sexual advances in a psychiatric setting (50 percent compared with 11 percent; χ2=20.48, df=1, p<.001), inadequate privacy (46 percent compared with or 11 percent; χ2=16.68, df=1, p<.001), and sexual assault by a staff member (17 percent compared with no respondents; χ2=18.90, df=1, p<.001). These patterns held after the analyses adjusted for age.

PEQ results by PTSD severity

With the Bonferroni correction, no statistical differences were found in reports of traumatic or harmful psychiatric experiences by whether patients met the criteria for probable PTSD.

Perceptions of personal safety, helplessness, fear, and distress

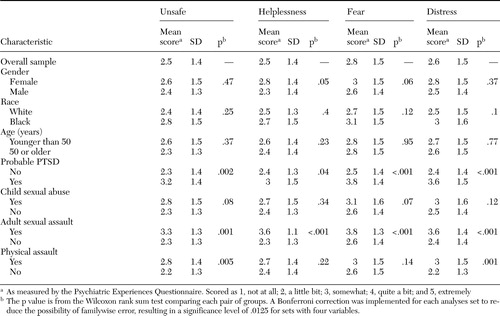

As shown in Table 4, when patients were asked whether they ever felt unsafe during their psychiatric care, they responded as feeling "a little bit" or "somewhat" unsafe (mean score of 2.5±1.4); the median response was feeling "a little bit" unsafe (score of 2.0). Table 4 also shows the scores for perceptions of personal safety, helplessness, fear, and distress in the psychiatric setting for the total sample. We used a Bonferroni correction of alpha=.0125 and conducted comparisons on these four variables by demographic characteristics, presence of probable PTSD, and lifetime trauma history. No significant gender, race, or age differences were found in these variables. However, significant differences were found by presence of probable PTSD and lifetime trauma history. Participants who met the criteria for having probable PTSD had significantly higher scores across three categories of perceptions than those who did not. Participants who met the criteria for probable PTSD reported feeling less safe, being more fearful, and being more distressed in psychiatric settings.

Among the lifetime traumatic events, respondents with a history of sexual assault as an adult reported significantly higher levels of concern for personal safety, helplessness, fear, and distress in psychiatric settings than those without such a history. Respondents with a history of physical assault reported significantly higher levels of concern for personal safety and distress.

Compliance with psychiatric recommendations

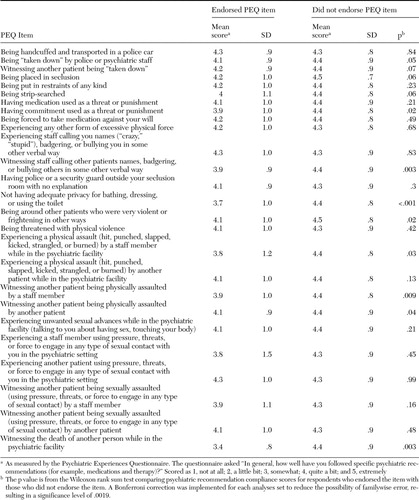

In general, high levels of reported compliance with psychiatric recommendations were found, as indicated by a mean compliance score of 4.3 ("quite a bit") and a median score of 5 ("extremely"). A total of 119 respondents (84 percent) reported a score of 4 or higher, and only seven (5 percent) reported a score of 1 or 2 ("not at all" or "a little bit"). We conducted analyses to determine whether differences existed in reported compliance between those who endorsed each traumatic or harmful psychiatric experience and those who did not. We used a Bonferroni correction and found only one significant association: as shown in Table 5, reported compliance was significantly worse among participants who also reported experiencing inadequate privacy while in a psychiatric setting. However, in future hypothesis-driven studies it might be worth examining this issue more closely, because an additional eight items showed uncorrected significance levels of p<.05 or less.

Discussion

This study provides strong empirical support for concerns raised by consumer and advocacy groups about patient safety within psychiatric settings. In a sample of patients with severe mental illness who were served by a public mental health clinic, high rates of lifetime trauma occurring within psychiatric settings were reported, including physical assault (31 percent), sexual assault (8 percent), and witnessing traumatic events (63 percent). In addition to events that met DSM-IV criteria for trauma, high rates of potentially harmful experiences were reported, such as having medications used as a threat or punishment (20 percent), being called names by staff (14 percent) or hearing staff call other patients names (19 percent), and being around frightening or violent patients (54 percent). Also rates of institutional measures of last resort were high, including seclusion (59 percent), restraint (34 percent), takedowns (29 percent), and handcuffed transport (65 percent). These data also demonstrate that both traumatic and harmful experiences were associated with psychological distress.

After correction for familywise error, virtually no statistically significant differences were found in the frequency of sanctuary events by individual demographic variables, such as gender, race, or age. However, analyses revealed that patients who reported a lifetime history of sexual assault as an adult on the TAA were more likely to report certain potentially harmful events on the PEQ, including unwanted sexual advances, inadequate privacy, and sexual assault by psychiatric staff. These patients also reported significantly higher levels of concern for personal safety and feelings of helplessness, fear, and distress in psychiatric settings. Interestingly, no statistically significant differences were found in the frequency of sanctuary events between patients who met the criteria for probable PTSD and those who did not, although those who met the criteria for probable PTSD reported feeling less safe, more fearful, and more distressed in psychiatric settings.

These findings should generate concern for several reasons. First, this population is vulnerable. All these patients had severe mental illness combined with high rates of lifetime trauma exposure (87 percent) and probable PTSD (19 percent). Second, trauma exposure to sexual assault as an adult outside the psychiatric setting was associated with specific traumatic and harmful events inside the sanctuary of the psychiatric setting. Third, having probable PTSD, a history of sexual assault as an adult, and a history of physical assault were associated with perceptions of imperiled safety, fear, and distress within psychiatric settings. Fourth, one potentially harmful sanctuary event, inadequate privacy, was associated with reported reduced compliance with psychiatric recommendations. And finally, the data suggest that patients report significant distress associated with a range of staff behaviors, from sanctioned measures of last resort to name-calling and physical assaults. Although the findings do not address causality, there is reason to believe that the experiences documented in this study may have an adverse effect on the mental health of this vulnerable population.

This was a cross-sectional, retrospective study that examined events occurring at any point during the participants' lifetime and did not specifically assess for recent events. Therefore, the extent to which psychiatric patients may be currently experiencing these events is unknown. The generalizability of these findings may also be somewhat limited. Participants were all from a single community mental health program. Furthermore, the data do not address causal relationships, and it is possible that some form of systematic recall or response biases were in operation. Patients may have been reluctant to report certain experiences or reactions, or conversely, they may have taken the opportunity to complain or misrepresent their experiences or reactions. Additional hypothesis-driven research is needed to replicate and extend these findings with other relevant groups, to refine our understanding of how frequently these events currently occur in psychiatric settings, to enhance our understanding of issues related to race and gender, and to begin to develop an understanding of strategies for quality improvement.

Conclusions

Results suggest that traumatic and harmful experiences within psychiatric settings warrant increased attention from mental health administrators, supervisors, and clinicians. We encourage key stakeholders in public-sector mental health systems to engage in discussion about policies, procedures, and training efforts; to be responsive to consumer initiatives; to reconsider administrative policies regarding seclusion and restraint; and to be sensitive to issues related to trauma in order to ensure that psychiatric settings provide care that is safe, dignified, and humane.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by grants MH-01660 and MH-65517 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Frueh, Dr. Grubaugh, Dr. Monnier, and Ms. Sauvageot are with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and Dr. Knapp and Ms. Yim are with the department of biometry at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. Dr. Frueh, Dr. Grubaugh, and Dr. Monnier are also with the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Charleston. Dr. Cusack and Dr. Hiers are with the South Carolina Department of Mental Health in Charleston. Ms. Cousins is with the South Carolina Department of Mental Health in Columbia. Dr. Robins is with Westat in Rockville, Maryland. Send correspondence to Dr. Frueh at the Medical University of South Carolina, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 67 President Street, P.O. Box 250861, Charleston, South Carolina 29425 (e-mail, [email protected]). This article is part of a special section on the use of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric treatment settings.

|

Table 1. Results on the Psychiatric Experiences Questionnaire (PEQ) for 142 persons with severe mental illness served in a public mental health system

|

Table 2. Results on the Psychiatric Experiences Questionnaire (PEQ) for 142 persons with severe mental illness served in a public mental health system, by history of childhood sexual assault and lifetime physical assault

|

Table 3. Results of the Psychiatric Experiences Questionnaire (PEQ) for 142 persons with severe mental illness served in a public mental health system, by history of adult sexual assault

|

Table 4. Comparison of perceptions of personal safety, helplessness, fear, and distress for the overall sample and by demographic characteristics, presence of probable PTSD, and lifetime trauma history among 142 persons served in a public mental health system

|

Table 5. Psychiatric recommendation compliance scores among 142 persons with severe mental illness served in a public mental health system, by endorsement of items on the Psychiatric Experiences Questionnaire (PEQ)

1. Cusack KJ, Frueh BC, Brady KT: Trauma history screening in a community mental health center. Psychiatric Services 55:157–162,2004Link, Google Scholar

2. Mueser K, Goodman LA, Trumbetta SL, et al: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:493–499,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Cohen LJ: Psychiatric hospitalization as an experience of trauma. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 8:78–81,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Frueh BC, Dalton ME, Johnson MR, et al: Trauma within the psychiatric setting: conceptual framework, research directions, and policy implications. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 28:147–154,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. NASMHPD Position Statement on Services and Supports to Trauma Survivors. Alexandria, Va, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, 2005Google Scholar

6. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services: Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Hospital Conditions of Participation: Clarification of the Regulatory Flexibility Analysis for Patients' Rights. Federal Register 67:61,805–61,808,2002Google Scholar

7. Frueh BC, Cusack KJ, Hiers TG, et al: Improving public mental health services for trauma victims in South Carolina. Psychiatric Services 52:812–814,2001Link, Google Scholar

8. Appelbaum PS: Seclusion and restraint: Congress reacts to reports of abuse. Psychiatric Services 50:881–882, 885,1999Link, Google Scholar

9. Fisher WA: Restraint and seclusion: a review of the literature. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1584–1591,1994Link, Google Scholar

10. Forster PL, Cavness C, Phelps MA: Staff training decreases use of seclusion and restraint in an acute psychiatric hospital. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 13:269–271,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Petti TA, Mohr WK, Somers JW, et al: Perceptions of seclusion and restraint by patients and staff in an intermediate-term care facility. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 14:115–127,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Meyer H, Taiminen T, Vuori T, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms related to psychosis and acute involuntary hospitalization in schizophrenic and delusional patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187:343–352,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Mohr WK, Mahon MM, Noone MJ: A restraint on restraints: the need to reconsider the use of restrictive interventions. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 12:95–106,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Rogers A, Pilgrim D, Lacey R: Experiencing Psychiatry: Users' Views of Services. Basingstoke, NH, MacMillan, 1993Google Scholar

15. Susko M: Cries of the Invisible: Writings From the Homeless and Survivors of Psychiatric Institutions. Baltimore, Conservatory Press, 1991Google Scholar

16. Sheline Y, Nelson T: Patient choice: deciding between psychotropic medication and physical restraints in an emergency. Bulletin of the American Academic Psychiatry and the Law 21:321–329,1993Medline, Google Scholar

17. Outlaw FH, Lowery BJ: An attributional study of seclusion and restraint of psychiatric patients. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 8:69–77,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Gardner W, Lidz CH, Hoge SK, et al: Patients' revisions of their beliefs about the need for hospitalization. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1385–1391,1999Abstract, Google Scholar

19. Frame L, Morrison AP: Causes of posttraumatic stress disorder in psychotic patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:305–306,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Shaw K, McFarlane A, Bookless C: The phenomenology of traumatic reactions to psychotic illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 185:495–502,1997Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Shaw K, McFarlane A, Bookless C, et al: The aetiology of postpsychotic posttraumatic stress disorder following a psychotic episode. Journal of Traumatic Stress 15:39–47,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Gallop R, McCay E, Guha M, et al: The experience of hospitalization and restraint of women who have a history of childhood sexual abuse. Health Care for Women International 20:401–416,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Fagen-Pryor EC, Haber LC, Dunlap D, et al: Patients' views of causes of aggression by patients and effective interventions. Psychiatric Services 54:549–553,2003Link, Google Scholar

24. Ilkiw-Lavalle O, Grenyer BF: Differences between patient and staff perceptions of aggression in mental health units. Psychiatric Services 54:389–393,2003Link, Google Scholar

25. Cusack KJ, Frueh BC, Hiers TG, et al: Trauma within the psychiatric setting: a preliminary empirical report. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 30:453–460,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

27. Bloom, S. Creating sanctuary: Towards the evolution of sane societies. London, Routledge, 1997Google Scholar

28. Robins CS, Sauvageot JA, Cusack KJ, et al: Consumers' perceptions of negative experiences and "sanctuary harm" in psychiatric settings. Psychiatric Services 56:1134–1138,2005Link, Google Scholar

29. Resnick HS: Psychometric review of Trauma Assessment for Adults (TAA), in Measurement of Stress, Trauma, and Adaptation. Edited by Stamm BH. Lutherville, Md, Sidran Press, 1996Google Scholar

30. Goodman LA, Thompson KM, Weinfurt K, et al: Reliability of reports of violent victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder among men and women with serious mental illness. Journal of Traumatic Stress 12:587–599,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Rosenberg SD, et al: Psychometric evaluation of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder assessments in persons with severe mental illness. Psychological Assessment 13:110–117,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, et al: The PTSD Checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Presented at the Conference of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, Tex, Oct 1993Google Scholar

33. Blanchard EB, Jones AJ, Buckley TC, et al: Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behaviour Research and Therapy 34:669–673,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Ruggiero KJ, Del Ben K, Scotti JR, et al: Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version. Journal of Traumatic Stress 16:495–502,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar