Review of Treatment Recommendations for Persons With a Co-occurring Affective or Anxiety and Substance Use Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors review and evaluate the literature and guidelines on care for individuals with a co-occurring affective or anxiety disorder and substance use disorder. METHODS: MEDLINE and PsycINFO computerized searches of the English language literature were conducted for the period 1990-2002. These articles were supplemented with searches of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1990 to 2002) and with articles that were sent to the authors by experts in the field to review. Bibliographies of selected papers were hand searched for additional articles. From these searches a total of 219 articles were found, of which 127 were selected for review. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION: The literature shows that, over the past several decades, treatment for co-occurring disorders has undergone a broad shift in approach, from treating substance abuse before providing mental health care to providing simultaneous treatment for each disorder, regardless of the status of the comorbid condition. Many treatment recommendations are supported by a broad consensus. However, despite this broad agreement, recommendations are often not specific enough to guide clinical care. Most recommendations with specificity are for acute pharmacotherapy, but even specific recommendations lag behind current clinical practice. Although the use of psychotropic medication for mental illness is encouraged, experts disagree as to whether it is necessary to wait for abstinence before beginning pharmacotherapy. In addition, most diagnosis-specific guidelines are silent as to whether the specific treatment recommendation applies to co-occurring disorders. Finally, empirical evidence is lacking for most recommendations. The authors conclude that the mental health and substance abuse treatment fields need to consider its research priorities and how to address the multitude of potential combinations of disorders.

The co-occurrence of mental and substance use disorders is prevalent, costly, and a service priority for state mental health and substance abuse agencies (1,2,3,4,5,6). States are increasingly being asked to provide evidence-based services to persons with dual diagnoses and their families (7,8). These dual diagnosis clients include those who have serious mental illness and a substance use disorder as well as those who have an affective or anxiety disorder who do not meet formal criteria for a serious mental illness and who typically enter treatment through the substance abuse treatment system rather than the mental health system (9,10). Both clinicians and program administrators look to treatment guidelines and other reviews of the empirical evidence to help them decide what services to implement. Policy makers use treatment guidelines to hold the service system accountable for providing evidence-based care.

There are two types of guidelines that address co-occurring disorders: guidelines that were specifically written for co-occurring disorders, and guidelines written for individual mental health and substance use disorders that address comorbidity as a complicating factor. A substantial body of literature based on empirical research exists regarding the treatment of persons with serious mental illness and a co-occurring substance use disorder (11). This literature has been influential in changing the way providers and program administrators deliver care to individuals with a dual diagnosis and how policy makers fund and organize such care (7,8).

However, the treatment models developed for this population may not be applicable to persons with a co-occurring affective or anxiety and substance use disorder, because the research on which it is based is specific to individuals with serious mental illness—usually psychotic disorders. This discrepancy is important, because a majority of persons with a dual diagnosis have a co-occurring affective or anxiety disorder, which is not a severe and persistent mental illness (2,4). Furthermore, the widespread application of these models to broader populations would involve substantial effort and expense.

To our knowledge, no systematic reviews have been conducted of the treatment literature for individuals with a nonserious mental illness that summarize both the mental health and substance abuse treatment recommendations and the evidence behind the recommendations. A recent review of the literature on co-occurring disorders (12) did not summarize the findings into recommendations with accompanying levels of evidence, and the review was directed toward substance abuse treatment providers.

In this article we review and evaluate the literature and guidelines on care for individuals with a co-occurring affective or anxiety and substance use disorder. Our objective is to describe how standard treatment practices should be modified when delivered to persons with co-occurring disorders. We identify specific clinical recommendations and the evidence supporting each recommendation. We also discuss the comprehensiveness of the recommendations, identify gaps, and point out how some of the recommendations conflict. We hope that this paper will serve as a document that will be useful to clinicians and program administrators as well as state mental health and substance abuse agencies who want to achieve better outcomes for persons with co-occurring disorders by increasing access to and improving the delivery of evidence-based care.

Methods

We conducted MEDLINE and PsycINFO computerized searches of the English-language literature for the period 1990-2002, using the search terms "guideline*," "treatment," "algorithm," "protocol," and "parameter" plus each of the following key words: "major depression," "depression," "dysthymia," "generalized anxiety disorder," "panic disorder," "manic depression," "PTSD," "bipolar disorder," "substance*," "drug*," "alcohol," "opiate*," "cocaine," and "marijuana." We searched separately for the key words "dual diagnosis," "coexisting," "co-occurring," and "comorbid," along with the key words "substance*," "mental health," and "psych*." We supplemented these articles with searches of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1990 to 2002) and with articles that were sent to us by experts in the field to review. Web sites for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration were queried for each of the search strings: "treatment guidelines," "coexisting," "co-occurring," or "dual diagnosis." Bibliographies of selected papers were hand searched for additional articles. From these searches a total of 219 articles were found, of which 127 were selected for review.

Article titles and abstracts were reviewed to determine inclusion eligibility. All practice guidelines and treatment algorithms pertaining to specific affective and anxiety disorders and to substance abuse were included, as were review articles and government-sponsored consensus documents on the treatment of co-occurring disorders. Articles were excluded if they reported on results of a single program evaluation, if they did not pertain to persons with affective or anxiety disorders and substance use, or if they did not include adults.

The articles we included were abstracted into recommendation tables, which were checked and rereviewed by the research team for clarity and placement of the recommendation in the table. We abstracted the original text of the recommendation to capture important specifications and noted the populations and settings to which the recommendation applied. The tables also summarized the level of evidence behind each recommendation on the basis of four categories: recommendation supported by the results of randomized outcome studies, results of studies with quasi-experimental designs, case studies, and expert opinion. In cases in which the guideline or review article did not give enough detail on the target population or level of evidence, we went back to the original articles cited in the review.

Results and discussion

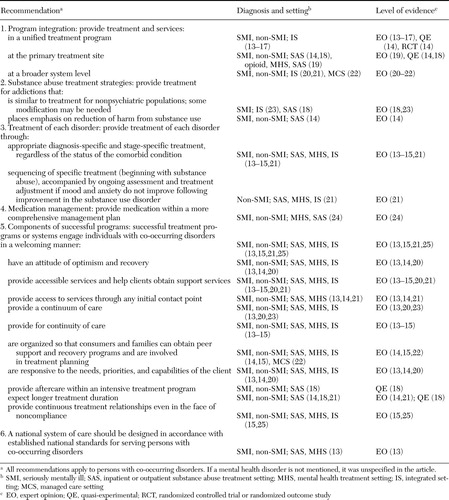

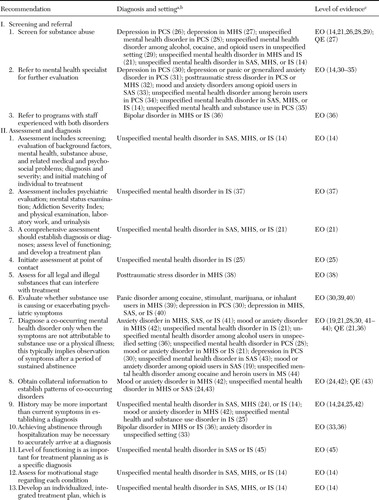

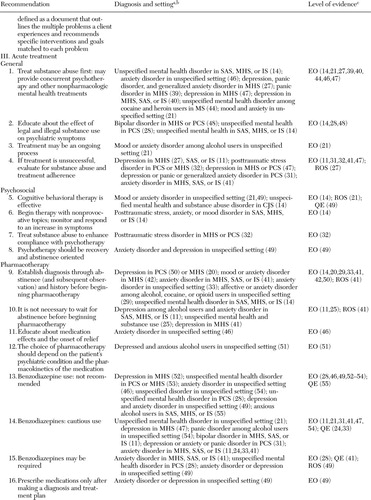

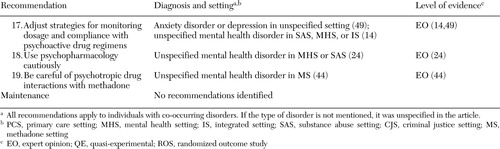

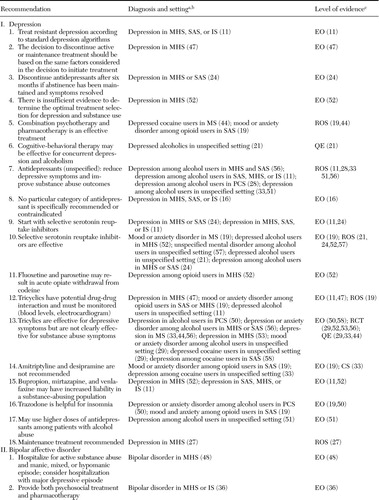

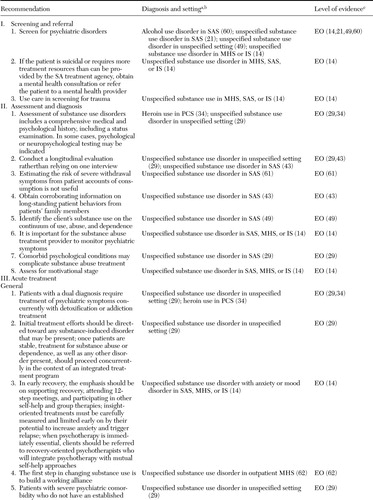

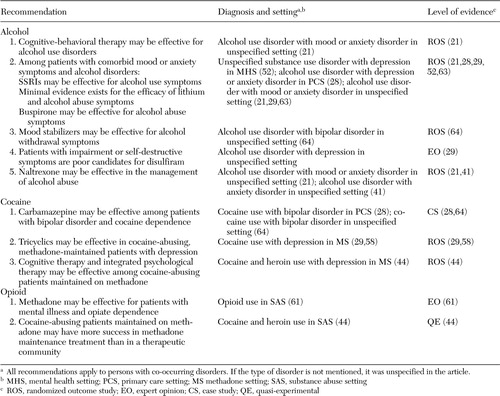

We grouped similar recommendations into three categories: program and system-level recommendations (Table 1), general (Table 2) and diagnosis-specific (Table 3) mental health treatment recommendations, and substance abuse treatment recommendations (Tables 4 and 5) (13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64). Recommendations concerning clinical care for a mental health disorder were assigned to the mental health treatment recommendations category, and those concerning care for substance abuse were assigned to the substance abuse treatment category, regardless of the treatment setting or whether it was the disorder for which the patient was in treatment.

Table 1 shows program and system-level recommendations for co-occurring disorders. Almost all of the six recommendations are supported only by expert opinion and include many precepts widely held by the field. The recommendations include integration of treatment and services, treatment provision for each disorder, and a list of successful treatment program components. A majority of the 35 recommendations in Table 2 are supported solely by expert opinion (N=25). Only five of the recommendations are supported by the highest level of empirical rigor, a randomized outcome study, of which three involve pharmacologic intervention. The 62 recommendations in Table 3 include some recommendations that are common to people without co-occurring disorders and some that are unique to this population. Thirty-eight of the 62 recommendations in Table 3 are supported only by expert opinion. Thirty-two of the 36 general substance abuse recommendations included in Table 4 are supported by expert opinion. Stronger empirical evidence is offered for some of the recommendations involving psychosocial intervention. As can be seen in Table 5, only ten recommendations were found for specific substance use disorders (alcohol, cocaine, and opioid use); however, eight of these recommendations are supported by strong empirical evidence. Many of these recommendations involve pharmacologic intervention.

This article reviews treatment recommendations for co-occurring affective or anxiety and substance use disorders and specifies the level of evidence in support of each recommendation. We include recommendations that are in conflict to highlight where the field has not yet reached consensus or where empirical evidence is lacking. To our knowledge, this is the first review of treatment recommendations that specifically focuses on individuals with a co-occurring affective or anxiety and substance use disorder and that includes the level of evidence behind each recommendation.

Over the past several decades treatment for co-occurring disorders has undergone a broad shift in approach, from treating substance abuse before providing mental health care to providing simultaneous treatment for each disorder, regardless of the status of the comorbid condition (13,14,15,16,1721). This shift appears to be driven by at least two factors. Although mental disorders may be the direct result of substance abuse, epidemiologic data indicate that most mental disorders temporally precede substance abuse, which suggests that they are two independent disorders and that the substance abuse is exacerbating rather than causing the mental disorder (2,4). A second factor has been the growing recognition that treatment approaches that focus on treating the substance abuse first have not been successful because substance use disorders tend to be episodic and recurrent. It is simply not feasible to expect acute treatment of substance use disorders to result in sustained recovery and thereby pave the way for a simpler approach to treating the mental disorder. Concurrently, there has been an increasing emphasis on psychopharmacology for the treatment of mental disorders, a shift that parallels changes occurring in the treatment of mental disorders among persons who do not have a substance use disorder.

Many treatment recommendations are supported by broad consensus. All diagnosis-specific guidelines recommend that clinicians screen for the presence of a comorbid condition. Similarly, it is broadly believed to be important to conduct a longitudinal evaluation and obtain corroborating diagnostic information from the client's friends and family. It is also recommended that clients be evaluated as to whether they have a substance-induced mental disorder or a separate axis I disorder that is causing the psychiatric symptoms and that they be educated about the side effects of medications and be given information about when they should expect symptoms to improve. All guidelines and reviews for co-occurring disorders recommend some form of "integrated" treatment.

Key issues identified by the review Recommendations lack specificity. Despite broad agreement, recommendations for the treatment of co-occurring disorders often are not specific enough to guide clinical care. For example, the intervals at which screening should occur and the instruments that should be used are not clear. Also unspecified is the level of workforce competency needed for various treatment tasks. There is no guidance on which of the competing treatments are optimal, and for which clients. This lack of clinical specificity is important, because it means that it is difficult for clinicians and administrators to implement the recommendations.

The definition of "integrated" treatment is particularly problematic. Some authors consider integrated treatment to be a unified treatment program, in which staff is cross-trained and both mental health and substance abuse treatment providers share the same treatment chart and treatment plan. (13,14,15,16,17). Others consider co-location of mental health and substance abuse services or the provision of both types of service at the primary treatment site to be integrated treatment (14,18,19). Still others consider integrated treatment to be the integration of services at a broader system level through interorganizational linkages and referrals (20,21,22). The lack of a common definition or operational taxonomy that specifies the different types of integrated treatment makes it difficult for public and private payers to evaluate the appropriateness of treatments and to compare alternative approaches.

Recommendations lag behind current practices. Most recommendations that have specificity are for acute pharmacotherapy, but even specific recommendations lag behind current clinical practice. Many studies have evaluated the use of tricyclic antidepressants for populations with co-occurring disorders; fewer studies have looked at the use of newer antidepressants (65). Yet tricyclics are rarely prescribed now that newer agents are available, so treatment recommendations concerning them are of little relevance.

Some recommendations reflect disagreement about important details. Although the use of psychotropic medication for mental illness is encouraged, experts disagree as to whether it is necessary to wait for abstinence before pharmacotherapy is started (11,14,20,25,29,33,41,42,50). This disagreement does not vary by the specific substances being abused or by the type of mental illness. Although abstinence is the ultimate goal of substance abuse treatment for co-occurring disorders, the relative importance of harm reduction as an interim goal is unclear. These important questions are yet to be resolved.

Recommendations in diagnosis-specific guidelines do not specifically apply to persons with co-occurring disorders. Although most diagnosis-specific guidelines contain a small section documenting the importance of co-occurring disorders, diagnosis-specific guidelines are often silent as to whether the specific treatment recommendations apply to co-occurring disorders (29,30,3139,47). Thus there is no evidence for important treatment questions such as how long psychotropic medication should continue once symptoms have remitted, whether and for how long maintenance treatment for substance use or mental disorders is recommended, and whether methadone is efficacious for individuals with opiate addiction who have co-occurring disorders. In the absence of evidence, the presumption is that clinicians should use the same guidelines to treat persons with co-occurring disorders as they use to treat those with a single disorder.

Empirical evidence is lacking for most recommendations. Perhaps the most important issue revealed by our review is that empirical evidence is lacking for most recommendations. Of particular importance is the lack of evidence for the recommendation to treat patients with co-occurring disorders in integrated treatment settings, the need for specialist assessment, and the sequencing of substance abuse and mental health treatment. Most recommendations are supported by expert opinion, and there are few randomized—or even quasi-experimental—designs. When empirical evidence exists, it is usually diagnosis and setting specific, yet the recommendations we found in conducting this review are framed in more general terms. In addition, many recommendations are not easily evaluated for efficacy, such as the recommendation that successful treatment programs be welcoming and accessible and convey an attitude of optimism and recovery.

Some recommendations are supported by empirical evidence, including the recommendation to screen for substance abuse (27) and the effectiveness of specific treatments for depression and anxiety disorders (11,19,21,24,27,28,2932,33,36,41,4446,49,50,51,5256,57) and for substance abuse (21,28,29,41,4452,58,63,64).

Conclusions

The results of this review present several challenges and dilemmas. Patients who are seen in clinical practice commonly have multiple problems, yet the efficacy data we have almost always come from treatments of single illnesses. In the absence of data, good practice suggests that each illness should be treated with the most effective treatments for the single illness. However, it would be useful to have more information about how standard treatment approaches should be modified for co-occurring disorders. Without efficacy data and performance measures, it is difficult for public and private payers to evaluate the appropriateness of treatments and hold agencies accountable for evidence-based care.

The enormous number of potential combinations of disorders means that it is unlikely that there will ever be efficacy data for most combinations of disorders. The mental health field needs to consider its research priorities and how to address the multitude of potential combinations. As a first step, we might consider research on treatments and illness combinations that are highly prevalent, or research on treatments with immediate clinical impact. Second, rather than evaluating single treatments or interventions, it may be most useful to evaluate "packages" of best practices that could be applied to a range of disorders. Finally, research related to treatment effects and the realities of implementation in community settings may have more relevance to clinicians and program administrators who are interested in informing clinical management decisions.

The authors are affiliated with RAND Corporation, 1776 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, California 90407-2138 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Program- and system-level treatment recommendations for persons with a co-occurring affective or anxiety disorder and substance use disorder

|

Table 2. Treatment recommendations for persons with a co-occurring affective or anxiety disorder and substance use disorder (general mental health)

|

Table 2b.

|

Table 2c.

|

Table 3. Treatment recommendations for persons with a co-occurring affective or anxiety disorder and substance use disorder (specific affective or anxiety disorders)

|

Table 4. Treatment recommendations for persons with a co-occurring affective or anxiety and substance use disorder (general substance use disorders)

|

Table 5. Treatment recommendations for persons with a co-occurring affective or anxiety disorder and substance use disorder (alcohol, cocaine, and opioid disorders)

1. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. JAMA 264:2511–2518,1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, et al: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:17–31,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health Report: Adults with Co-occurring Serious Mental Illness and a Substance Use Disorder. June 23, 2004. Available at http://oas.samhsa.gov/2k4/cooccurring/cooccurring.cfmGoogle Scholar

4. Kandel DB, Huang FY, Davies M: Comorbidity between patterns of substance use dependence and psychiatric syndromes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 64:233–241,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Dickey B, Azeni H: Persons with dual diagnosis of substance abuse and major mental illness: their excess costs of psychiatric care. American Journal of Public Health 86:973–977,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA: The cost of treating substance abuse patients with and without comorbid psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Services 50:1309–1315,1999Link, Google Scholar

7. Strategies for Developing Treatment Programs for People With Co-occurring Substance Abuse and Mental Disorders. Pub no 3782. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003Google Scholar

8. SAMHSA National Advisory Council: Improving Services for Individuals at Risk of, or With, Co-occurring Substance-Related and Mental Health Disorders. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1997Google Scholar

9. Primm AB, Gomez MB, Tzolova-Iontchev I, et al: Mental health versus substance abuse treatment programs for dually diagnosed patients. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 19:285–290,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hien D, Zimberg S, Weisman S, et al: Dual diagnosis subtypes in urban substance abuse and mental health clinics. Psychiatric Services 48:1058–1063,1997Link, Google Scholar

11. Mueser KT, Noordsy DL, Drake RE, et al: Integrated Treatment for Dual Disorders: A Guide to Effective Practice. New York, Guilford, 2003Google Scholar

12. Cacciola J, Dugosh K: Co-occurring Substance Use and Mental Disorders: An Annotated Bibliography. Philadelphia, DeltaMetrics, 2003Google Scholar

13. Principles for Care and Treatment of Persons With Co-occurring Psychiatric and Substance Disorders. Pittsburgh, Pa, American Association for Community Psychiatrists, Feb 26, 2000Google Scholar

14. Substance Abuse Treatment for Persons With Co-occurring Disorders. Draft. Treatment Improvement Protocol 20. Rockville, Md, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, Sept 2002Google Scholar

15. Minkoff K: Behavioral health recovery management service planning guidelines co-occurring psychiatric and substance disorders. Guidelines developed for the Behavioral Health Recovery Management Project. Unpublished manuscript. Boston, 2001Google Scholar

16. Integrated Dual Disorders Treatment Implementation Resource Kit: Evidence-Based Practices: Shaping Mental Health Services Toward Recovery. Draft. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2002Google Scholar

17. Fine J, Miller NS: Evaluation and management of psychotic symptomatology in alcohol and drug addictions. Journal of Addictive Diseases 12:59–71,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Moggi F, Ouimette PC, Finney JW, et al: Effectiveness of treatment for substance abuse and dependence for dual diagnosis patients: a model of treatment factors associated with one-year outcomes. Journal of Studies in Alcohol 60:856–866,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Nunes EV, Donovan SJ, Brady R, et al: Evaluation and treatment of mood and anxiety disorders in opioid-dependent patients. Journal of Psychedelic Drugs 26:147–153,1994Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Osher FC: A vision for the future: toward a service system responsive to those with co-occurring addictive and mental disorders. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:71–76,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health: Best Practices: Concurrent Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders. Health Canada, 2001. Available at www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hecs-sesc/cds/pdf/concurrentbestpractice.pdfGoogle Scholar

22. Minkoff K: Co-occurring Psychiatric and Substance Disorders in Managed Care Systems: Standards of Care, Practice Guidelines, Workforce Competencies, and Training Curricula. Report of the Center for Mental Health Services Managed Care Initiative: Clinical Standards and Workforce Competencies Project. Co-occurring Mental and Substance Disorders Panel. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, Jan 1998Google Scholar

23. Minkoff K: Models for addiction treatment in psychiatric populations. Psychiatric Annals 24:412–417,1994Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Sowers W, Golden S: Psychotropic medication management in persons with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 31:59–70,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Minkoff K: State of Arizona Service Planning Guidelines: Co-occurring Psychiatric and Substance Disorders. Unpublished manuscript. Boston, Nov 2000Google Scholar

26. US Preventive Services Task Force: Screening for depression: recommendations and rationale. Annals of Internal Medicine 136:760–764,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Health Care Guideline: Major Depression in Adults for Mental Health Providers. Bloomington, Minn, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, May 2002Google Scholar

28. Brady KT: Recognizing and treating dual diagnosis in general health care settings: core competencies and how to achieve them. Substance Abuse 23(suppl 3):143–154,2002Google Scholar

29. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders: alcohol, cocaine, opioids. American Journal of Psychiatry 152(Nov suppl):1–59,1995Google Scholar

30. Veterans Health Administration: The Pharmacologic Management of Major Depression in the Primary Care Setting. Pub no 00–0016. May 2000Google Scholar

31. Health Care Guideline: Major Depression, Panic Disorder, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Adults in Primary Care. Bloomington, Minn, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, May 2002Google Scholar

32. Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Expert Consensus Panels for PTSD. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 16):3–76,1999Medline, Google Scholar

33. Gastfiend DR: Pharmacologic treatment of dual diagnosis. Journal of Addictive Diseases 12:155–170,1993Crossref, Google Scholar

34. O'Connor P, Feillin DA: Pharmacologic treatment of heroin-dependent patients. Annals of Internal Medicine 133:40–54,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Veterans Health Administration/Department of Defense: Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Substance Use Disorders in the Primary Care Setting, version 1.0. Washington, DC, April 2001Google Scholar

36. Brady KT, Sonne SC: The relationship between substance abuse and bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56(suppl 3):19–24,1995Medline, Google Scholar

37. Daley D: Dual disorders recovery counseling, in NIDA Approaches to Drug Abuse Counseling. NIH pub no 00–4151. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, July 2000Google Scholar

38. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, eds: Guidelines for treatment of PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress 13:539–588,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guidelines for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 155(May suppl), 1998Google Scholar

40. Osser DN: Algorithm for the pharmacotherapy of depression. Available at www.mhc.com/algorithms/depression/index.htm, version 2.7, Jan 24, 2003Google Scholar

41. Osser DN, Renner JA, Bayog R: Consultant for the pharmacotherapy of anxiety in patients with chemical abuse and dependence. Available at www.mhc.com/algorithms/anxiety/index.htm, version 2.9, June 9, 2003Google Scholar

42. Anthenelli RM, Schuckit MA: Affective and anxiety disorders and alcohol and drug dependence: diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Addictive Diseases 12:73–87,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Weiss RD, Mirin SM, Griffin ML: Methodological considerations in the diagnosis of coexisting psychiatric disorders in substance abusers. British Journal of Addiction 87:179–187,1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Assessment and Treatment of Cocaine-Abusing Methadone-Maintained Patients. Treatment Improvement Protocol 10. Rockville, Md, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1994Google Scholar

45. Little J: Treatment of dually diagnosed clients. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 33:27–31,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Albrant DH: APhA Drug treatment protocols: management of patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association 38:543–550,1998Google Scholar

47. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder (revision). American Journal of Psychiatry 157(Apr suppl), 2000Google Scholar

48. Expert Consensus Guideline: Treatment of bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 12A), 1996Google Scholar

49. Landry MJ, Smith DE, Steinberg JR: Anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders: diagnosis, treatment, and prescribing practices. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 23:397–416,1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. A Guide to Substance Abuse Services for Primary Care Clinicians. Treatment Improvement Protocol 24. Rockville, Md, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1997Google Scholar

51. Swift RM: Drug therapy for alcohol dependence. New England Journal of Medicine 340:1482–1490,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Enns MW, Swenson JR, McIntyre RS, et al: Clinical guidelines for the treatment of depressive disorders: VII. comorbidity. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 46(suppl 1):77S-90S,2001Google Scholar

53. Ballenger JC, Davidson JRT, Lecrubier Y, et al: Consensus statement on generalized anxiety disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62(suppl 11):53–58,2001Medline, Google Scholar

54. Nelson J, Chouinard G: Guidelines for the clinical use of benzodiazepines: pharmacokinetics, dependency, rebound, and withdrawal. Canadian Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 6:69–83,1999Medline, Google Scholar

55. Kranzler HR: Evaluation and treatment of anxiety symptoms and disorders in alcoholics. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57 (suppl 7):15–21,1996Medline, Google Scholar

56. Nunes EV, Quitkin FM: Treatment of depression in drug-dependent patients: effects on mood and drug use. NIDA Research Monograph 172:61–85,1997Medline, Google Scholar

57. Treatment of Depression: Newer Pharmacotherapies. AHCPR pub no 99-E014. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Feb 1999Google Scholar

58. Schottenfeld R, Carroll K, Rounsaville B: Comorbid psychiatric disorders and cocaine abuse. NIDA Research Monograph 135:31–47,1993Medline, Google Scholar

59. Report of Center for Mental Health Services Managed Care Initiative Clinical Standards and Workforce Competencies Project Co-occurring Mental and Substance Disorders Panel: Co-occurring Psychiatric and Substance Disorders in Managed Care Systems: Standards of Care, Practice Guidelines, Workforce Competencies, and Training Curricula. January 1998Google Scholar

60. Weinrieb RM, O'Brien CP: Naltrexone in the treatment of alcoholism. Annual Review of Medicine 48:477–487,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

61. Kofoed L: Outpatient vs inpatient treatment for the chronically mentally ill with substance use disorders. Journal of Addictive Diseases 12:123–137,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

62. Carey KB: Substance use reduction in the context of outpatient psychiatric treatment: a collaborative, motivational, harm reduction approach. Community Mental Health Journal 32:291–306,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

63. Pharmacotherapy for Alcohol Dependence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 3. AHCPR pub no 99-E004. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Jan 1999Google Scholar

64. Ries RK: The dually diagnosed patient with psychotic symptoms. Journal of Addictive Disorders 12:103–122,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

65. Nunes EV, Levin FR: Treatment of depression in patients with alcohol or other drug dependence: a meta-analysis. JAMA 291:1887–1896,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar