Association Between Concurrent Depression and Anxiety and Six-Month Outcome of Addiction Treatment

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This six-month prospective study of 326 patients with substance use disorders assessed rates of depression and anxiety symptoms among patients entering addiction treatment and examined the effects of concurrent psychiatric symptoms on indicators of addiction treatment outcome. METHODS: Initial assessments included semistructured clinical interviews, the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and the Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL90-R). Patients were reassessed at six months to determine treatment outcome (abstinence status and duration of continuous abstinence). RESULTS: A majority of the sample (63 percent) had significant psychiatric symptoms at intake: 15 percent (N=49) presented with depressive symptoms, 16 percent (N=53) with anxiety symptoms, and 32 percent (N=105) with combined depressive and anxiety symptoms. Forty percent of patients who presented with combined depression and anxiety symptoms were abstinent at six months. These patients fared worse than those who were less symptomatic at intake, including those who presented with depression symptoms alone; in the latter group, 73 percent were abstinent at six months. The hierarchical regression models accounted for 22 percent of the variance in the duration of continuous abstinence, 26 percent of the variance in the frequency of drug use at six months, and 39 percent of the variance in abstinence status at six months. Key predictor variables included days in treatment, primary drug of abuse, frequency of drug use, and report of concurrent depression or anxiety symptoms at intake. CONCLUSIONS: Concurrent depression or anxiety symptoms at intake had a small but significant predictive effect on addiction treatment outcome over and above factors that are clearly known to influence outcome (length of stay in treatment and initial addiction severity).

Concurrent depression and anxiety symptoms are among the most common problems reported by persons seeking treatment for substance use disorders (1,2,3,4,5). Some individuals experience dysphoria or agitation secondary to chronic substance use or withdrawal. Others consume alcohol or drugs to mitigate these psychiatric symptoms. Although substance-induced depression and anxiety may improve significantly with a sustained period of abstinence (DSM-IV suggests four weeks), primary psychiatric symptoms persist beyond detoxification and remission of addictive behavior. Clinical guidelines recommend waiting until four weeks of abstinence before diagnosing or treating depression or anxiety among patients who are actively using alcohol or drugs. Unfortunately, in an outpatient setting, it often takes several months for patients to sustain four weeks of abstinence. From an addiction perspective, there may be significant risks associated with concurrent depression and anxiety symptoms, regardless of etiology. Symptoms such as anhedonia, impaired concentration, hopelessness, and agitation may lead to an inability to engage in treatment and to sustain abstinence.

A number of studies have indicated that patients with concurrent psychiatric and substance use disorders have worse prognoses than those with no psychopathology, including a decreased rate of remission, an increased vulnerability to relapse, and a need for more treatment services (6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14). For example, Greenfield and colleagues (8) reported that among 101 patients hospitalized for alcohol dependence, a diagnosis of major depression at admission to the hospital predicted shorter time to first drink and relapse after treatment. Driessen and colleagues (13) investigated the impact of concurrent anxiety and depressive disorders on 100 alcohol-dependent patients in the postdetoxification period and found higher relapse rates among patients with concurrent psychiatric disorders: 40 percent for patients with no psychopathology, 69 percent for those with anxiety, and 77 percent for those with both anxiety and depression.

However, some studies have suggested that depression may convey a better prognosis (15,16,17) or that depression has no impact on the outcome of addiction treatment (18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25). Rounsaville and colleagues (16) followed 227 patients who sought treatment for alcohol dependence and initially found that women with a lifetime diagnosis of depression had better drinking outcomes one year after treatment than women without depression. In a 23-year follow-up of the same patients, lifetime depression was associated with reduced intensity of drinking among both men and women (15). However, patients with lifetime diagnoses may have had no distressing symptoms at intake; some of the inconsistent results may be attributed to this failure to distinguish between current and past depression diagnoses (15,16,22,24).

Initial studies conducted at the McGill University Health Center (MUHC) addictions unit found that patients with substance use disorders who had moderate to severe symptoms of depression at intake, as indicated by a score of more than 18 on the Beck Depression Inventory, had a 20 percent higher rate of early dropout (within the first 60 days of treatment) (26). In a subsequent prospective study at the same unit (20,27), patients with a current diagnosis of depression, as established by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV), fared as well as the nondepressed patients in terms of all outcome measures at six months (20). However, the patients with depression received more treatment than those without depression. It may be that additional treatment compensated for greater depression psychopathology among these patients with dual diagnoses. Because of the smaller sample (N=120), it was not possible to consider the predictive effects of other psychopathology, such as anxiety, either with or without concurrent depression, on treatment outcome.

The study reported here adds to the existing literature in that it involved the analysis of a substantially larger sample of treatment-seeking patients with substance use disorders (N=326), which allowed us to consider the predictive effects of concurrent symptoms of both depression and anxiety on addiction treatment outcome. Initial assessments included semistructured clinical interviews, the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and the Symptom Checklist 90-Revised (SCL90-R). Patients were reassessed at six months to determine treatment outcome (abstinence status and duration of continuous abstinence). The objectives of this study were to assess rates of depression and anxiety symptoms, regardless of their etiology, among patients entering addiction treatment and to examine the effects of these concurrent symptoms—depression alone, anxiety alone, and depression and anxiety combined—on indicators of addiction treatment outcome.

Methods

Participants

The sample included patients who were consecutively recruited upon entering treatment at the MUHC addictions unit. The addictions unit provides comprehensive ambulatory care to adults with psychoactive substance use disorders. It pursues a treatment philosophy of total abstinence and provides integrated care for concurrent psychiatric disorders. All patients were eligible for the study—there were no exclusion criteria. Patients were informed about study procedures as well as the risks and benefits of standard treatment. A total of 326 patients provided written informed consent, and six declined to participate. The study's procedure and consent form were approved by the MUHC research ethics committee. The study was conducted from January 1996 to December 2000.

Procedure

Initial assessments were conducted by trained interviewers, who collected detailed information about demographic characteristics, current and lifetime substance use, and medical, psychiatric, and family histories through use of a semistructured clinical interview. All patients completed self-report questionnaires that measured psychological distress (the SCL-90-R) (28) and depressive symptoms (the BDI) (29). The study participants provided a urine sample for drug screening (CEDIA, or cloned enzyme donor immunoassay). Initial assessments were reviewed by an addictions unit psychiatrist, who conducted a brief clinical interview to screen for suicidal ideation, psychosis, or other psychiatric conditions that necessitated immediate intervention.

During the six-month follow-up study, the study participants were offered standard treatment: outpatient detoxification, one or two 90-minute group therapy sessions per week, at least four 50-minute individual therapy sessions, and random urine drug screens throughout treatment. The 90-minute group therapy sessions combined psychoeducational, supportive, and relapse prevention interventions to help them adjust to an alcohol- and drug-free lifestyle, examine the function that alcohol or drugs had served in their lives, identify and cope with high-risk situations, and resolve problems that impede psychological growth and social adjustment. The 50-minute individual psychotherapy sessions emphasized and promoted self-efficacy and personal responsibility for change, evaluated and enhanced the patients' motivational level and readiness for change, and educated the patients about strategies that produce change and prevent relapse. The expected duration of treatment was six to nine months.

All addiction therapists had more than five years' experience as addiction counselors and held degrees in nursing, occupational therapy, or psychology. They met weekly with psychiatrists to discuss their patients' progress and any need for psychiatric interventions. Psychiatric treatment was provided if indicated by the initial assessment or if later requested by the patient's therapist. If patients were unable to tolerate or adhere to outpatient detoxification regimens, they were offered inpatient detoxification. Patients were encouraged, but not required, to attend mutual help groups.

At six months, all patients, including those who had dropped out of treatment, were recontacted and invited to attend follow-up interviews. Follow-up interviews were independent of treatment visits and were conducted by a research assistant who was uninvolved in clinical care. Study participants were questioned about the outcome of treatment (abstinence status and duration of continuous abstinence), psychological distress (SCL-90-R), and depressive symptoms (BDI). The participants were again asked to provide a urine sample for drug screening. Individuals who were unable to return for follow-up visits or who were reluctant to do so were interviewed by telephone.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted with use of the microcomputer version of SPSS (version 11.5). Associations were examined by using the chi square test for categorical data, and comparisons between groups or time points were assessed by using analysis of variance, including those for multiple variables and repeated measures. Post hoc tests were conducted by using Tukey's, Scheffe's, or t tests with a Bonferroni correction. Relationships between demographic, substance use, and psychiatric predictor variables and addiction outcome measures were assessed by using multiple hierarchical regression techniques for continuous outcome measures and logistic regression techniques for categorical outcome measures.

Results

Sample description

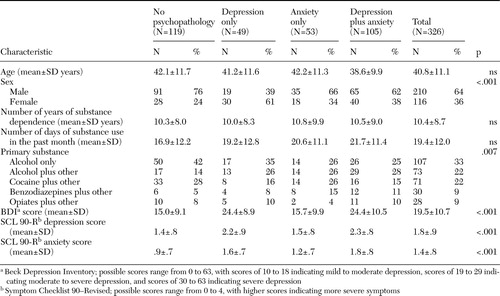

Demographic, substance use, and psychiatric characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. The sample of 326 patients was a mixed population of adults with substance use disorders and was predominantly white (93 percent) and male (64 percent), with a mean age of 40.8 years. The sample was divided into four groups on the basis of patients' report of concurrent psychiatric symptoms during the initial semistructured interviews—no psychopathology, depression only, anxiety only, and depression plus anxiety. A majority of the sample (63 percent) had significant psychiatric symptoms at intake: 15 percent (N=49) presented with depressive symptoms, 16 percent (N=53) with anxiety symptoms, and 32 percent (N=105) with combined depressive and anxiety symptoms.

The four psychopathology groups differed in demographic characteristics. The depression-only group was predominantly female, whereas the other three groups were predominantly male (χ2=21.95, df=4, p<.001). The four psychopathology groups also differed in terms of their primary substance: the group with no psychopathology was more likely to abuse alcohol only, whereas the three groups with concurrent psychopathology were more likely to abuse alcohol in conjunction with other drugs (χ2=31.94, df=15, p=.007).

A high degree of correlation was observed between the four psychopathology groups and the psychiatric self-report measures. The two depression groups (depression only and depression plus anxiety) had elevated scores on the BDI (F=24.22, df=3, 319, p<.001) and on the SCL depression subscale (F=19.74, df=3, 322, p<.001), whereas all three groups with concurrent psychopathology (depression only, anxiety only, and depression plus anxiety) had elevated scores on the SCL anxiety subscale (F=16.11, df=3, 322, p<.001).

Service use during the six-month follow-up period

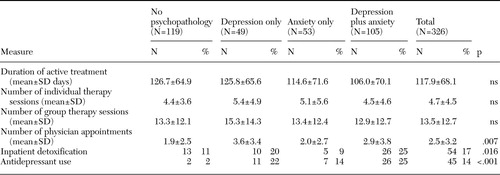

Review of treatment records showed that 162 patients (54 percent) were still in treatment at six months, with a mean duration of treatment of 117.9±68.1 days. When the sample was divided into four groups on the basis of patients' report of concurrent psychiatric symptoms during the initial semistructured interviews (no psychopathology, depression only, anxiety only, and depression plus anxiety), significant differences were noted among the groups in terms of their use of treatment services (Table 2). The group with depression only and the group with depression plus anxiety were more likely to require inpatient detoxification than the groups without depression (χ2=10.32, df=3, p=.052) and were more likely to receive prescriptions for new antidepressant medication regimens (χ2=26.79, df=3, p<.001). The four groups also required different levels of psychiatric care (F=4.10, df=3, 319, p=.007). Post hoc analysis (Scheffe's) indicated that the depression-only group attended significantly more psychiatric appointments than the group with no psychopathology (p=.025). No other pairwise differences were observed.

Antidepressant use was associated with lower rates of early dropout (11 percent compared with 29 percent; χ2=6.16, df=1, p=.013) and increased retention in treatment (138 days compared with 113 days; t=-2.64, df=309, p=.010). Antidepressant use during addiction treatment was determined retrospectively by chart review. Specifically, patients were considered to have received a new regimen if a new antidepressant medication was initiated, if a second medication was added, or if the dosage of an existing medication was increased. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were the most commonly prescribed antidepressant medications.

Outcome of addiction treatment at six months

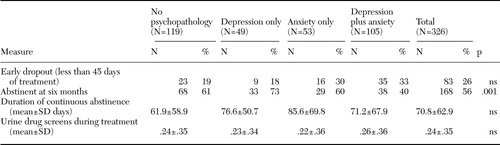

A total of 300 (92 percent) of the 326 patients with substance use disorders participated in the six-month follow-up interviews (250 face-to-face and 50 telephone interviews). A total of 56 percent of patients were abstinent at six months, with a mean duration of 70.8±62.9 days of continuous abstinence. When the sample was divided into four groups on the basis of patients' report of concurrent psychiatric symptoms during their initial semistructured interviews (no psychopathology, depression only, anxiety only, and depression plus anxiety), significant differences were noted among the groups in abstinence status (Table 3). The group with depression plus anxiety had the lowest rate of abstinence at six months (χ2=16.75, df=3, p=.001).

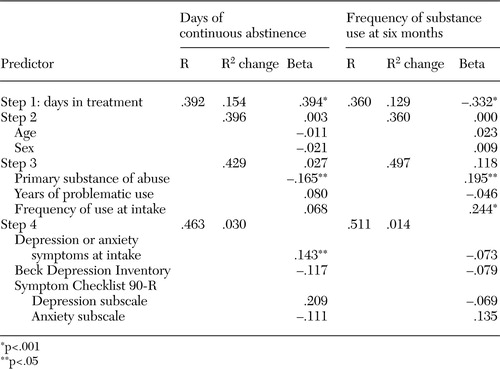

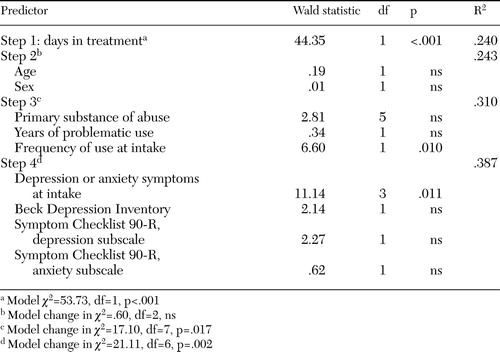

Hierarchical regression analyses were performed for the continuous and categorical outcome variables (Tables 4 and 5). In each analysis, groups of predictor variables were added to models by using forward stepwise variable selection (SPSS 11.5). The models were constructed to determine the predictive effects of psychopathology (concurrent depression or anxiety symptoms) at intake on addiction treatment outcome over and above factors that are clearly known to influence outcome. Previous research has indicated that the time spent in treatment is a predictor of abstinence after treatment (30,31). Thus the number of days spent in treatment was used as a covariate in all regression analyses. The order of entry of predictor variables in the regression analyses was as follows: days in treatment was entered in the first step, demographic variables (age and sex) were entered in the second step, indicators of initial addiction severity (primary drug, frequency of drug use at intake, and duration of problem drug use) were entered in the third step, and measures of psychopathology at intake (concurrent depression or anxiety symptoms during the initial semistructured clinical interviews and scores on psychometric measures) were entered in the final step.

The hierarchical multiple regressions predicting days of continuous abstinence and frequency of drug use at six months are summarized in Table 4. The model accounted for 22 percent of the variance in the number of days of continuous abstinence (F=7.10, df=10, 270, p<.001). Predictors that were significant in the final model included number of days in treatment (p<.001), primary drug of abuse (p=.006), and report of concurrent depression or anxiety symptoms at intake (p=.020). The model accounted for 26 percent of the variance in the frequency of drug use at six months (F=9.15, df=10, 269, p<.001). Predictors that were significant in the final model included length of stay in treatment (p<.001), primary drug of abuse (p=.001), and frequency of drug use at intake (p<.001). The logistic regression predicting abstinence status at six months is summarized in Table 5. The model accounted for 39 percent of the variance in abstinence status (χ2=92.55, df=16, p<.001). Predictors that remained significant in the final model included length of stay in treatment (p<.001), frequency of drug use at intake (p=.010), and report of concurrent depression or anxiety symptoms at intake (p=.011).

Discussion

This study assessed rates of concurrent psychiatric symptoms among 326 patients entering addiction treatment and examined the effects of these symptoms on the outcome of addiction treatment. The results revealed that a majority of the patients in the sample (63 percent) had significant psychiatric symptoms at intake into addiction treatment, with 32 percent (N=105) presenting with combined depressive and anxiety symptoms. The elevated rates of comorbid psychiatric illness are similar to those found in other studies of addiction treatment populations (1,2,3,4,5). The 116 female patients had significantly higher rates of comorbid depression than the 210 male patients. The sex ratio for the prevalence of depression was approximately 2:1, which is consistent with large community surveys of individuals with substance use disorders (32) and those without (33).

In this study, there was an association between patients' report of concurrent psychiatric symptoms during the initial semistructured interviews and their addiction treatment outcomes at six months. Specifically, 40 percent of patients who presented with combined depression and anxiety symptoms at intake were abstinent at six months. These patients fared worse than those who were less symptomatic at intake, including those who presented with depression symptoms alone—in the latter group, 73 percent were abstinent at six months. The low abstinence rate of patients with substance use disorders who presented with combined depression and anxiety symptoms is similar to that found by Driessen and colleagues (13).

The relatively good six-month outcome of patients who presented with depression symptoms alone may have been due, in part, to an overrepresentation of patients with alcohol dependence in this group. Patients with alcohol dependence generally fare better in addiction treatment than those with other drug dependencies (34). The better six-month outcome of the depression-only group may also be related to the higher levels of psychiatric care they received compared with the patients who did not have depression. They had more psychiatric appointments, and they were more likely to require inpatient detoxification and to be given a prescription for new antidepressant medication regimens (largely SSRIs). Antidepressant use was associated with lower rates of early dropout (11 percent compared with 29 percent; χ2=6.16, df=1, p=.013) and increased retention in treatment (138 days compared with 113 days; t=-2.64, df=309, p=.010). The increased length of stay in treatment may have enhanced individuals' ability to engage in treatment and to make use of the psychotherapy counseling offered at the clinic.

The relatively poor six-month outcome of patients who presented with combined symptoms of depression and anxiety may have been due, in part, to an overrepresentation of patients with prescription drug dependence in this group (40 percent of benzodiazepine-dependent patients and 39 percent of opiate-dependent patients were in the group with both depression and anxiety). Earlier studies have shown that benzodiazepine and opiate-dependent patients have lower rates of achieving abstinence and shorter periods of continuous abstinence (19,34). The worse six-month outcome of the group with both depression and anxiety may also be linked to the direct effects of their multiple symptoms (anhedonia, agitation, impaired concentration, and hopelessness) on patients' ability to engage in treatment and sustain abstinence. Another possible explanation is that there was an excess of personality disorders among patients with both depression and anxiety. The psychopathology groups were defined by their symptoms at intake, not by diagnoses; individuals with personality disorders tend to report high levels of depression and anxiety and to be included in the more symptomatic groups. Earlier studies have shown that patients with comorbid personality disorders have a poorer response to SSRIs and a poorer prognosis overall (35,36,37).

Results of the regression analyses demonstrated that the predictor variables added to the model accounted for 22 percent of the variance in the duration of continuous abstinence, 26 percent of the variance in the frequency of drug use at six months, and 39 percent of the variance in abstinence status at six months. In each analysis, the time in treatment emerged as the most important predictor of addiction treatment outcome. This finding is consistent with the results of previous research, which has demonstrated that the number of days spent in treatment is correlated with abstinence after treatment (30,31). Patients' report of concurrent psychiatric symptoms at intake was a significant independent predictor of abstinence but accounted for a smaller portion of the explained variance—approximately 3 percent of the variance in the duration of continuous abstinence and 8 percent of the variance in abstinence status at six months.

While in treatment at the addictions unit, patients were encouraged, but not required, to attend mutual help groups. One limitation of this study is that patients' involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous or other 12-step programs was not measured and therefore was not added to the regression models. Attending 12-step meetings has been shown to be associated with better addiction outcome at six months and five years (38). However, no causal link has been established. The positive correlation between abstinence and attendance at 12-step meetings may indicate that compliant patients, who are able to follow treatment recommendations, do better in general. Other measures of treatment adherence were included in the regression analyses—for example, number of days in treatment. It is unclear whether attendance at 12-step meetings would have emerged as an independent predictor of addiction outcome beyond number of days in treatment.

Conclusions

The findings of this study complement and extend previous research on psychopathology and addiction treatment outcome. Patients who presented with symptoms of both depression and anxiety at intake were significantly less likely to be abstinent at six months than patients who had no psychiatric symptoms or who had symptoms of depression only. Results of the regression analyses demonstrated that concurrent psychiatric symptoms at intake had a small but significant predictive effect on addiction treatment outcome, over and above factors that are clearly known to influence outcome, such as length of stay in treatment and initial addiction severity.

Dr. Charney , Dr. Palacios-Boix, Dr. Negrete, and Dr. Gill are affiliated with the addictions unit at McGill University Health Centre and with the department of psychiatry of McGill University in Montreal. Dr. Dobkin is with the division of clinical epidemiology at McGill University Health Centre and with the department of Medicine of McGill University. Send correspondence to Dr. Charney at Addictions Unit, McGill University Health Centre, 1604 Pine Avenue West, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3G 1B4 (e-mail, [email protected]). A version of this paper was presented at the annual scientific meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism held in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, June 21 to 25, 2003.

|

Table 1. Demographic, substance use, and psychiatric characteristics of a sample of patients at addiction treatment intake

|

Table 2. Use of treatment services during the six-month follow-up period in a sample of 326 patients entering substance abuse treatment

|

Table 3. Outcome of addiction treatment at six months

|

Table 4. Multiple regression analysis of clinical predictors of addiction treatment outcome at six months in a sample of 326 patients entering substance abuse treatment

|

Table 5. Logistic regression analysis of clinical predictors of abstinence at six months

1. Hesselbrock M, Meyer RE, Keener JJ: Psychopathology in hospitalized alcoholics. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:1050–1055,1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Ross HE, Glaser FB, Germanson T: The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in patients with alcohol and other drug problems. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:1023–1031,1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Rounsaville BJ, Anton SF, Carroll K, et al: Psychiatric diagnoses of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:43–51,1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Rounsaville BJ, Weissman MM, Kleber HD, et al: Heterogeneity of psychiatric diagnoses in treated opiate addicts. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:161–166,1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Schuckit MA: Genetic and clinical implications of alcoholism and affective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:140–147,1986Link, Google Scholar

6. Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Shifman RB: Do substance abuse patients with more psychopathology receive more treatment? Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:576–582,1993Google Scholar

7. Bobo JK, McIlvain HE, Leed-Kelly A: Depression screening scores during residential drug treatment and risk of drug use after discharge. Psychiatric Services 49:693–695,1998Link, Google Scholar

8. Greenfield SE, Weiss RD, Muenz LR, et al: The effect of depression on return to drinking: a prospective study. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:259–265,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Loosen PT, Dew BW, Prange AJ: Long-term predictors of outcome in abstinent alcoholic men. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:1662–1666,1990Link, Google Scholar

10. Moos RH, Mertens JR, Brennan PL: Rates and predictors of four-year readmission among late-middle-aged and older substance abuse patients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 55:561–570,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Rounsaville BJ, Kosten TR, Weissman MM, et al: Prognostic significance of psychiatric disorders in treated opiate addicts. Archives of General Psychiatry 43:739–745,1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hasin DS, Tsai WY, Endicott J, et al: The effects of major depression on alcoholism: five-year course. American Journal on Addictions 5:144–155,1996Google Scholar

13. Driessen M, Meier S, Hill A, et al: The course of anxiety, depression, and drinking behaviours after completed detoxification in alcoholics with and without comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders. Alcohol and Alcoholism 36:249–255,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Willinger U, Lenzinger E, Hornik K, et al: Anxiety as a predictor of relapse in detoxified alcohol-dependent patients. Alcohol and Alcoholism 37:609–612,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kranzler HR, Del Boca FK, Rounsaville BJ: Comorbid psychiatric diagnosis predicts three-year outcomes in alcoholics: a posttreatment natural history study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 57:619–626,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Rounsaville BJ, Dolinsky ZS, Babor TF, et al: Psychopathology as a predictor of treatment outcome in alcoholics. Archives of General Psychiatry 44:505–513,1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Westermeyer J, Kopka S, Nugent S: Course and severity of substance abuse among patients with comorbid major depression. American Journal on Addictions 6:284–292,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Araujo L, Goldberg P, Eyma J, et al: The effect of anxiety and depression on completion withdrawal status in patients admitted to substance abuse detoxification program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 13:61–66,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Charney DA, Paraherakis AM, Gill KJ: The treatment of sedative-hypnotic dependence: evaluating clinical predictors of outcome. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:190–195,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Charney DA, Paraherakis AM, Gill KJ: Integrated treatment of comorbid depression and substance use disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62:672–677,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Davidson KM, Blackburn IM: Co-morbid depression and drinking outcome in those with alcohol dependence. Alcohol and Alcoholism 33:482–487,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Miller NS, Hoffman NG, Ninonuevo F, et al: Lifetime diagnosis of major depression as a multivariate predictor of treatment outcome for inpatients with substance use disorders from abstinence-based programs. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 9:127–137,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Miller NS, Klamen D, Hoffman NG, et al: Prevalence of depression and alcohol and other drug dependence in addictions treatment populations. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 28:111–124,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Sellman JD, Joyce PR: Does depression predict relapse in the months following treatment for men with alcohol dependence? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 30:573–578,1996Google Scholar

25. Schuckit MA: The clinical implications of primary diagnostic groups among alcoholics. American Journal of Psychiatry 142:1043–1049,1985Link, Google Scholar

26. Gauthier G, Paraherakis A, Gill KJ: Examining factors that may affect dropout in addiction treatment: a look at the assessment and engagement process. Canadian Health Psychologist 5:40–45,1997Google Scholar

27. Charney DA, Paraherakis AM, Negrete JC, et al: The impact of depression on the outcome of addictions treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 15:123–130,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Derogatis L: Symptom Checklist-90-Revised: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual II. Towson, Md, Clinical Psychometrics Research, 1992Google Scholar

29. Beck AT, Steer RA: Beck Depression Inventory. New York, Harcourt Brace, 1987Google Scholar

30. Brewer DD, Catalano RF, Haggerty K, et al: A meta-analysis of predictors of continued drug use during and after treatment for opiate addiction. Addiction 93:73–92,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Toumbouro JW, Hamilton M, Fallon B: Treatment level progress and time spent in treatment in prediction of outcomes following drug-free therapeutic community treatment. Addiction 93:1051–1064,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, et al: Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:313–321,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Weissman MM, Bland R, Joyce PR, et al: Sex differences in rates of depression: cross-national perspectives. Journal of Affective Disorders 29:77–84,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Paraherakis AM, Charney DA, Palacios-Boix J, et al: Abstinence-oriented program for substance use disorders: poorer outcome associated with opiate dependence. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 45:927–931,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Nace EP, Davis CW: Treatment outcome in substance-abusing patients with a personality disorder. American Journal on Addictions 2:26–33,1993Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Nurnberg HG, Rifkin A, Doddi S: A systematic assessment of the comorbidity of DSM-III-R personality disorders in alcoholic outpatients. Comprehensive Psychiatry 34:447–454,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Verheul R, van den Brink W, Hartgers C: Personality disorders predict relapse in alcoholic patients. Addictive Behaviors 23:869–882,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Weisner C, Thomas R, Mertens JR et al: Short-term alcohol and drug treatment outcomes predict long-term outcome. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 71:281–294,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar