Relationship Between Criminal Arrest and Community Treatment History Among Patients With Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the relationship between criminal arrest and gender, substance use disorder, and use of community mental health services among patients with bipolar I disorder. METHODS: Los Angeles County's computerized management information system was used to retrospectively identify all inmates with a DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar I disorder who were evaluated over a seven-month period in the psychiatric division of Los Angeles County Jail and had a history of psychiatric hospitalization in the community. Patients without a history of arrest who were involuntarily hospitalized in the community and treated for bipolar I disorder over the same seven-month period served as a comparison group. The use of community mental health services that inmates received before their arrest was quantified and compared with the services that patients in the comparison group received before their involuntary hospitalization. RESULTS: Patients who had been arrested (N=66) were more likely than patients in the comparison group (N=52) to be male (55 percent compared with 31 percent) and to have a history of substance use disorder (76 percent compared with 19 percent) but were less likely to have a history of treatment while under a mental health conservatorship (8 percent compared with 29 percent). In contrast to patients in the comparison group, patients who had been arrested were hospitalized more frequently (a mean of 3.4 hospitalizations per year compared with a mean of 1.1 hospitalizations per year) and had a briefer average length of stay (a mean of 9.2 days compared with a mean of 16.4 days). CONCLUSIONS: In contrast to patients in the comparison group, patients who had been arrested were more likely to be male, to have comorbid substance use disorder, and to have a treatment history characterized by more frequent, briefer hospitalizations.

Evidence is accumulating that suggests that criminal arrest and incarceration complicate the course of bipolar I disorder for a substantial proportion of patients. A recent screening survey for bipolar disorder that used the Mood Disorders Questionnaire found that 26 percent of men who screened positive for bipolar disorder had a history of arrest for charges other than driving under the influence (1). The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study found that the prevalence of bipolar I disorder is six times higher in prisons than in the community at large (6 percent compared with 1 percent) (2). The criminalization of individuals with bipolar disorder and psychotic disorders appears to account for the dramatic rise in the number of inmates with mental illness in jails and prisons over the past 30 years (3,4).

A limited body of empirical data details differences between patients who enter the criminal justice system and those who can be effectively treated in community settings. Offenders with mental illness are more likely to be male; in jail populations, there are nearly eight times as many men as women (88.4 percent compared with 11.6 percent) (5). However, among persons with severe mental illness, women are as violent as men, which suggests that this vast gender difference in the jail population at large may not be as substantial when inmates with a severe mental disorder are examined (6). Persons with mental illness who are arrested are likely to have high rates of comorbid substance use disorder. Substance use disorder and treatment noncompliance has been shown to dramatically increase the risk of violent behavior among persons with mental illness (7,8), and inmates with mental illness are more likely than other inmates to be under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of arrest (9).

No study has specifically examined and quantified how offenders with mental illness use community mental health services, although it has been observed that many of these persons have had suboptimal community psychiatric treatment before their involvement with the criminal justice system (10,11). This suboptimal treatment could involve an overuse of inpatient services. In a study of inpatients with a psychotic disorder, the number of past admissions was an important predictor of history of arrest (12). Also, in a study of offenders with mental illness who were on probation, the number of lifetime manic episodes and frequency of hospitalizations were the most significant factors associated with the number of lifetime arrests (13). Offenders with mental illness may be patients who refuse to enter into and comply with outpatient care. In a study that examined clinical correlates at the time of arrest among inmates with bipolar I disorder at Los Angeles County Jail, 75 percent of inmates were arrested while experiencing a manic phase and 60 percent had been hospitalized in the month before they were jailed, but only 20 percent were involved in outpatient care at the time of arrest (14).

In this retrospective review of computerized treatment records, patients with bipolar disorder who were arrested while being treated in the community were compared with similar patients who were not arrested in an attempt to determine how these groups differ in gender, comorbid substance use disorder, and use of community mental health services (overall use of services, differences in outpatient and inpatient services, and length and frequency of hospitalization). Elucidating these differences may help inform policies and strategies for reducing criminal recidivism in this patient population.

Methods

Study site

Inmates in this study were identified at the psychiatric division of Los Angeles County Jail. Upon entry, all inmates are screened for mental illness at the inmate reception center before being housed in the jail. Those with a significant psychiatric history or active symptoms of mental illness are housed at Twin Towers Correctional Facility, which is the largest mental health facility serving the Los Angeles County region, with a daily census of approximately 2,700 inmates. The Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health provides psychiatric services for all inmates in the jail. The human subjects review committees of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health and the University of California, Davis, approved a waiver of informed consent.

Databases

Use of community psychiatric services, demographic characteristics, and clinical characteristics were determined from data obtained from the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health's management information system (MIS). Inpatient facilities and outpatient clinics use the MIS database to coordinate mental health services. For each patient, the location and dates of previous inpatient and outpatient treatment were recorded, along with the DSM-IV diagnosis for which the patient was treated. Each treatment contact also included a unit of service, which represented the extent of service use at a given treatment location. One standard unit of service is equivalent to one outpatient appointment, one inpatient day, or one emergency department visit. The MIS records use of psychiatric services in both community and forensic treatment settings, including the Twin Towers Correctional Facility. Los Angeles County psychiatrists make diagnoses on the basis of DSM-IV criteria after an evaluation and enter the information into the MIS. Demographic data are entered by mental health support staff.

Criminal history in Los Angeles County was determined through the use of the Los Angeles County Sheriff's consolidated criminal history reporting system. This system created a report that provided an overview of an individual's criminal history, including dates of past arrests and charges, dates of past convictions and sentences, and dates of parole or probation. In addition, some of the patients who had been arrested had periods of incarceration that interrupted their community treatment. To correct for this time out of the community, we used the consolidated criminal history reporting system to subtract days in jail or prison from the time in community treatment.

Participants

All male and female inmates aged 18 through 65 years and received a DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar I disorder at Twin Towers Correctional Facility over a designated seven-month period (January 1 through July 31, 2000) were identified in the MIS. Only those who had a previous record of community treatment in the Los Angeles County mental health system that included a psychiatric hospitalization with a discharge diagnosis of bipolar I disorder were investigated further. The previous inpatient diagnosis of bipolar disorder was required to improve diagnostic reliability; participants with more than one previous contact with the community treatment system were included in the analyses only if a majority of their past treatment was for bipolar I disorder. Inmates with no previous treatment or treatment exclusively in forensic settings were excluded.

As a means of comparison with the patients who had been arrested, a sample of Los Angeles County patients with bipolar disorder who had no known history of arrest during the course of their psychiatric treatment within Los Angeles County was identified. To match the two groups, we randomly selected patients with bipolar disorder who were involuntarily hospitalized for treatment and given a discharge diagnosis of bipolar I disorder (in any phase of illness) at each of Los Angeles County's four major psychiatric hospitals during the same designated seven-month period. We chose patients who were involuntarily hospitalized because the vast majority (84 percent) of past hospitalizations for arrested patients in this sample were involuntary and because involuntary community hospitalization has been shown to be associated with postrelease arrest among persons with mental illness (15). For inmates to be included in the study, a majority of past treatment had to be for bipolar I disorder.

Study variables

The MIS database codes substance use disorder, both as a DSM-IV diagnosis and as a separate "dual diagnosis" variable for each client. We reviewed all available data on substance use disorder for each participant, including types of substances that were abused.

In each group we quantified inpatient, outpatient, and total service use by using the unit of service measure. Number of hospitalizations per year and average length of hospitalization were also calculated. We also examined whether a patient had a history of treatment while under a mental health conservatorship, which is a civil commitment that lasts for one year. Patients under a conservatorship are assigned a conservator, who makes treatment decisions, makes housing placements, and manages finances for the conservatee.

Statistical analysis

The duration of use of Los Angeles County psychiatric services before the study period differed for each participant. To standardize service use measures, each measure (number of hospitalizations, inpatient days, and outpatient contact units) was divided by the total amount of time (in years) that a participant was in community treatment. All analyses were conducted by using SPSS for Windows, version 10.0.5; t tests and chi square analyses were performed to determine which categorical and continuous demographic and service use variables differed significantly between the two samples. A stepwise logistic regression procedure was performed by using the binary logistic regression procedure. The stepwise procedure was used because of the exploratory nature of the analysis. Logistic regression generally is used to determine the factors most associated with a binary dependent variable. Independent variables can be either categorical or continuous. Logistic regression can also be used to determine the factors that are best at discriminating between two groups, much the same as discriminant analysis. However, logistic regression is preferable when the variables are not normally distributed, an assumption of discriminant analysis.

Results

Differences in demographic characteristics

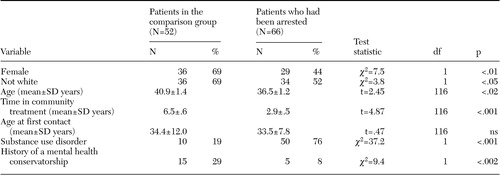

Sixty-six patients were in the group that had been arrested, and 52 patients were in the comparison group. In both samples, a variety of ethnicities were represented. Among patients who had been arrested, 32 (48 percent) were white, 21 (32 percent) were African American, ten (15 percent) were Hispanic, and three (5 percent) were Asian. Among patients in the comparison group, 16 (31 percent) were white, 18 (35 percent) were African American, 12 (23 percent) were Hispanic, and six (12 percent) were Asian. As shown in Table 1, when patients were grouped as being either white or a member of an ethnic minority group, persons from an ethnic minority group were overrepresented in the comparison group (36 patients in the comparison group, or 69 percent, were from an ethnic minority group, compared with 34 patients who had been arrested, or 52 percent). Gender also differed between the two groups (36 of 52 patients in the comparison group, or 69 percent, were female compared with 29 of 66 patients who had been arrested, or 44 percent). Patients in the comparison group were significantly older than patients who had been arrested (a mean±SD age of 40.9±1.4 compared with a mean age of 36.5±1.2 years).

Comorbid substance use disorder

In this sample, patients who had been arrested were significantly more likely than patients in the comparison group to have comorbid substance use disorder (50 patients who were arrested, or 76 percent, compared with ten patients in the comparison group, or 19 percent) (Table 1). Among patients who were arrested, 34 of 50 (68 percent) had a history of abusing one substance, and 16 of 50 (32 percent) had a history of abusing two or more substances. The most commonly abused substances were cocaine (28 patients, or 56 percent) and alcohol (25 patients, or 50 percent); marijuana (eight patients, or 16 percent), methamphetamine (four patients, or 8 percent), opiates (three patients, or 6 percent), and hallucinogens (two patients, or 4 percent) were also abused.

Community treatment history

As shown in Table 1, although the two samples differed both in terms of current age and time spent in community treatment, the average age of first contact with Los Angeles County community mental health did not differ between the two groups (a mean age of 34.4±12.0 years for patients in the comparison group compared with a mean age of 33.5±7.8 years among those who had been arrested), even after the analysis accounted for time spent in jail. Among patients who had been arrested, 45 (68 percent) had a period of incarceration that interrupted community treatment, even though the mean time spent in jail or prison was relatively brief (mean of 171.2±253.1 days) compared with the total period spent in community treatment (mean of 2.9 years).

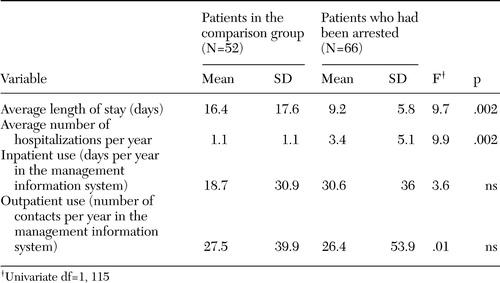

As shown in Table 2, no differences were found between the two groups for overall use of mental health services (both inpatient and outpatient use rates). The comparison group averaged 46.1±58 contact days per year, and the arrested group averaged 57.1±67.3. Furthermore, no differences were found between the two groups in use of outpatient services. The comparison group averaged 27.1±39.9 contacts per year, and the arrested group averaged 26.4±53.9 contacts per year. However, use of inpatient services differed significantly. Overall, there was a nonsignificant trend for patients who had been arrested to use inpatient services at a greater rate than those in the comparison group (mean of 30.7±30.6 days per year compared with a mean of 18.7±30.9). The manner in which inpatient services were used was markedly different between the two groups. Patients who had been arrested were hospitalized three times as frequently as patients in the comparison group (a mean of 3.4±5.1 hospitalizations per year compared with a mean of 1.1±1.1; t=3.15, df=115, p<.002). In contrast, the average stay for patients in the comparison group was almost twice that for patients in the arrested group (a mean of 16.4±17.6 days compared with a mean of 9.2±5.8; t=3.12, df=115, p<.002).

Patients in the comparison group were more likely than patients who had been arrested to have a history of receiving treatment in a mental health conservatorship (15 patients, or 29 percent, compared with five patients, or 8 percent) (Table 1).

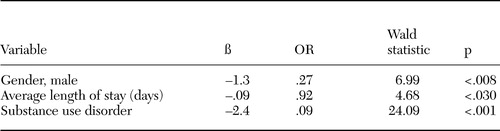

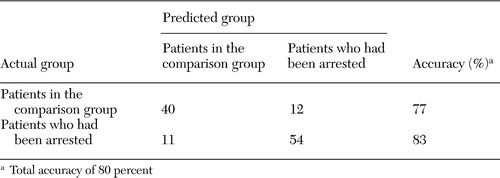

To determine the factors that were best at discriminating between the two groups, a logistic regression analysis was performed. To prevent a loss of power, only gender, substance use disorder, and service use variables (for example, average number of hospitalizations per year, average length of stay, and average number of outpatient contacts per year) were entered into the regression equation. As shown in Table 3, the following variables met the significance level criteria for entry (.05) and retention (.10) in the model and were found to discriminate between the two groups: gender (β=-1.31, p<.008), substance use disorder (β=-2.42, p<.001), and average length of stay (β=-.09, p<.030). By using these three variables, the overall classification rate was 80 percent, a 30 percent improvement over chance. However, as shown in Table 4, the model was slightly better at predicting membership in the arrested group than in the comparison group (83 percent accuracy compared with 77 percent).

Discussion

In this study we attempted to identify how patients with bipolar I disorder who were arrested during community treatment differed from those who were not arrested in terms of gender, comorbid substance use disorder, and use of community psychiatric services. Patients who were arrested were more likely to be male, to be younger, and to have comorbid substance use disorder. Compared with patients in the comparison group, patients who had been arrested had a high frequency of hospitalizations that were shorter in duration and rarely had extended treatment while under a mental health conservatorship.

Even though being male was significantly associated with being in the arrested group, the finding that 45 percent of patients in the arrested group were women is significant considering that only 10 percent of a jail population is female (16). This finding suggests that the potential for criminal arrest among women with bipolar disorder should not be underestimated.

Alcohol and drug abuse was a substantial factor in differentiating the two groups. The high prevalence (76 percent) of the diagnosis of substance use disorder among patients who had been arrested and had spent an average of three years in community treatment is substantially higher than the 60.7 percent estimated lifetime prevalence of comorbid substance use disorder among patients with bipolar disorder from Epidemiological Catchment Area Study data (17). Substance use disorder has been shown to increase psychiatric hospitalization rates among persons with mental illness. Patients with bipolar disorder and a substance use disorder are hospitalized twice as often as patients with bipolar disorder alone (18,19), and comorbid substance use disorder among patients with major psychotic and affective disorders is an important factor explaining increased frequency of psychiatric hospitalization (20).

Although frequency of hospitalization was significantly associated with having been arrested, a stronger predictor in the logistic regression was a brief duration of hospitalization. The specific reasons underlying the relatively brief hospital stay for patients who had been arrested were not investigated in this study. One possibility is that patients who had been arrested were more often released at civil commitment hearings. In California, after an initial three-day evaluation period, a patient can be held for two weeks of additional involuntary treatment if commitment criteria are met (allowing 17 days of hospitalization, which is close to the mean hospital stay of 16.4 days for nonoffending patients with bipolar disorder). The average duration of hospitalization for patients who had been arrested, 9.2 days, suggests that these patients were more often released at "probable cause" hearings, which occur five through nine days after admission. A prospective study of psychiatric inpatients in a community hospital supports this hypothesis (unpublished data, Stone D, 2004). Inpatients with bipolar disorder who were discharged at their probable cause hearing were significantly more likely to enter into jail treatment over the follow-up year than those who were held involuntarily for further treatment and stabilization.

The finding that patients in the comparison group were more often treated while under a mental health conservatorship also indicates that they were more often held in the hospital under civil commitment law, which may be an important factor explaining the longer average duration of hospitalization. We found that 29 percent of patients in the comparison group, compared with only 8 percent of patients who had been arrested, had been involuntarily treated while under a mental health conservatorship at some point during their community treatment. The process of obtaining a conservatorship requires three separate civil commitment hearings during an inpatient stay and leads to an extended hospitalization of 30 days or more.

Alternatively, patients who had been arrested may have been released in anticipation of civil commitment hearings because they did not meet criteria for continued involuntary treatment. Bipolar symptoms of patients who had been arrested could have been attributed to substance use, or the substance use could have altered the presenting symptoms of arrested patients. Patients with bipolar disorder and comorbid substance use disorder have been shown to present more often while experiencing episodes of dysphoric mania (19). Many of the arrested patients have had previous criminal involvement and may display aggressive or intimidating behaviors. Clinicians may be reluctant to pursue long-term hospitalization in community treatment facilities that are not as well-equipped as criminal justice settings for managing these behaviors (21).

Although these data demonstrate that the use of inpatient services differed significantly between patients in the two groups, conclusions about outpatient use patterns are less clear. We hypothesized that patients in the comparison group would be more willing to engage in outpatient treatment and use more outpatient services than the patients who were arrested. However, the two groups did not differ in the overall use of outpatient services. Even though overall use did not differ, it is possible that the way outpatient services were used did differ. For example, patients who had been arrested may have dropped out of care and changed outpatient service providers more frequently. In addition, because patients in the comparison group had longer hospitalizations, it is possible that they entered outpatient care in a more stable condition and required less outpatient contact than patients who had been arrested. A more detailed analysis of outpatient use patterns would be required to investigate this finding.

This study had several limitations. First, it relied on retrospective data that were obtained from a large computerized database. Like all research that relies on databases, the quality of the study results is limited by the quality of the database maintained. However, we had no reason to suspect that errors in data on the diagnosis, treatment, substance use disorder, and demographic characteristics should be greater in either group. Second, the diagnoses were not confirmed by a structured diagnostic interview at the time of arrest or at previous hospitalizations. We attempted to increase the reliability of the diagnosis by using the "clinical consensus" of Los Angeles County psychiatrists—that is, most of the patient's past discharge diagnoses had to be for a bipolar I diagnosis. In addition, no structured interview evaluated comorbid axis II conditions, which may be an important factor related to criminal arrest. Third, only inmates with bipolar disorder who had a history of hospitalization and treatment in the Los Angeles County community mental health system were included; this excludes those who received care through private insurance.

Conclusions

Among patients with bipolar I disorder, those who had been arrested during community treatment were more likely than those who were not arrested to be male and have comorbid substance use disorder. Their community treatment history was characterized by frequent, brief hospitalizations that rarely led to extended treatment while under a mental health conservatorship. Our findings have implications in efforts to reduce the likelihood of criminal arrest among patients with bipolar disorder. In community treatment settings, screening patients with bipolar disorder for substance use disorder, understanding how substances can alter the presentation of bipolar illness, and including drug and alcohol treatment as part of the management plan may lessen the risk of criminal arrest among these patients.

At a public policy level, the "criminalization of the mentally ill" is now being recognized as a problem, and efforts are being made to divert patients from criminal justice settings into community treatment. Several jurisdictions have experimented with using civil commitment statutes that favor treatment on an outpatient basis (22) and using mental health courts or diversion programs (23,24) that mandate psychiatric treatment by judicial order. These findings suggest that legal interventions that promote stabilization of mania in an inpatient setting and drug screening may also help prevent criminal offences among patients with bipolar disorder.

Dr. Quanbeck, Dr. McDermott, and Dr. Scott are with the forensic division of the department of psychiatry at the University of California-Davis, 2230 Stockton Boulevard, Sacramento, California 95817 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Frye is with the mood disorder research program of the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at David Geffen School of Medicine in Los Angeles. Dr. Stone and Dr. Boone are with the department of psychiatry at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, California. Preliminary results of this study were presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law held October 25 to 28, 2001, in Boston.

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with bipolar disorder, by legal status

|

Table 2. Differences in service use among patients with bipolar disorder, by legal statusa

aUnivariate df=1, 115

|

Table 3. Variables associated with history of arrest among patients with bipolar disordera

|

Table 4. Classification table for logistic regression model that predicted history of arrest among patients with bipolar disorder

1. Calabrese JR, Hirschfeld MA, Reed M, et al: Impact of bipolar disorder on a US community sample. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:425–432,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Robins LN, Regier DA: Psychiatric disorders in America, in The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

3. Quanbeck CD, Frye MA, Altshuler L: Mania and the law in California: understanding the criminalization of the mentally ill. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1245–1250,2003Link, Google Scholar

4. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE: Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatric Services 49:483–492,1998Link, Google Scholar

5. Profile of Jail Inmates, 2002. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, July 2004Google Scholar

6. Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment. Edited by Monahan J, Steadman H. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994Google Scholar

7. Swanson JW, Holzer CE, Gangu VK: Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: evidence from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area surveys. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:761–770,1990Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, et al: Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and nonadherence to medication. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:226–231,1998Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Mental Health and Treatment of Inmates and Probationers. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, July 1999Google Scholar

10. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE, Gross BH: Community treatment of severely mentally ill offenders under the jurisdiction of the criminal justice system: a review. Psychiatric Services 50:907–913,1999Link, Google Scholar

11. Lamb R, Grant RW: The mentally ill in an urban county jail. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:17–22,1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Muntaner C, Wolyniec P, McGrath J, et al: Arrest among psychotic inpatients: assessing the relationship to diagnosis, gender, number of admissions, and social class. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:274–282,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Solomon P, Draine J: Explaining lifetime criminal arrests among clients of a psychiatric probation and parole service. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 27:239–251,1999Medline, Google Scholar

14. Quanbeck CD, Stone DC, Scott CL, et al: Clinical and legal correlates of inmates with bipolar disorder at time of criminal arrest. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:198–203,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Crisanti AS, Love EJ: From one legal system to another? An examination between involuntary hospitalization and arrest. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 25:581–597,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 2001. Washington DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, April 2002Google Scholar

17. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. JAMA 264:2511–2518,1994Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Cassidy F, Ahearn EP, Carrol BJ: Substance abuse in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders 3:181–188,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Sonne SC, Brady KT, Morton WA: Substance abuse and bipolar affective disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:349–352,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, et al: Predicting the "revolving door" phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:856–861,1995Link, Google Scholar

21. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE, Gross BH: Community treatment of severely mentally ill offenders under the jurisdiction of the criminal justice system: a review. Psychiatric Services 50:907–913,1999Link, Google Scholar

22. Monahan J, Bonnie RJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Mandated community treatment: beyond outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services 52:1198–1205,2001Link, Google Scholar

23. Griffin PA, Steadman HJ, Petrilia J: The use of criminal charges and sanctions in mental health courts. Psychiatric Services 53:1285–1289,2002Link, Google Scholar

24. Cosden M, Ellens JK, Schnell JL, et al: Evaluation of a mental health treatment court with assertive community treatment. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 21:415–427,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar