The Use of Criminal Charges and Sanctions in Mental Health Courts

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study sought to describe the use of criminal charges, sanctions (primarily jail), and other strategies mental health courts use to mandate adherence to community treatment, and in doing so to elaborate on earlier descriptions of such courts. METHODS: Telephone interviews were conducted with staff of four mental health courts, located in Santa Barbara, California; Clark County, Washington; Seattle, Washington; and Marion County, Indiana. RESULTS: Mental health courts use one or more of three approaches to leverage the disposition of criminal charges to mandate adherence to community treatment: preadjudication suspension of prosecution of charges, postplea strategies that suspend sentencing, and probation. In no case are criminal charges dropped before the defendant becomes involved with the mental health court program. Each dispositional strategy includes adherence to community treatment as a condition. Courts report a wide variety of sanctions for failure to adhere to court-ordered conditions. CONCLUSIONS: Mental health courts use various creative methods of disposition of criminal charges to mandate adherence to community treatment. In contrast to drug courts, in which the use of jail and other sanctions for nonadherence is common, most mental health courts report rarely or occasionally using jail in this way.

The use of mental health courts—criminal courts that hear cases of individuals with mental illness who typically are charged with misdemeanors—is often proposed as a strategy to "decriminalize" people with mental illness (1). These special-jurisdiction courts, modeled on the increasingly popular drug courts, have been developed in response to the large numbers of persons with severe mental illness incarcerated in jails (2), their special needs while incarcerated, the difficulties courts face in effectively addressing mental illness issues, and the strains that involvement with the criminal justice system places on individuals with mental illness and their family members (3).

Although program descriptions and accounts of the development of individual mental health courts have been published (4,5,6) and evaluations of the effectiveness of some courts are under way (7), little is known about the effectiveness of such courts and their general operation. Despite the absence of published outcome data, Congress recently appropriated funds for the development of new mental health courts, and this type of court appears to be growing in popularity.

Goldkamp and Irons-Guynn (8) described four early mental health courts in Broward County (Ft. Lauderdale, Florida); King County (Seattle); San Bernardino, California; and Anchorage, Alaska. The authors characterized them as problem-solving courts that varied widely in structure and differed in part on the basis of the personal characteristics of the presiding judge. They outlined the organization of the courts, judicial process, case flow, approach to treatment, and disposition. Despite significant differences among the courts, the authors found three common elements. First, a mental health court is typically a specialty court or docket that handles only defendants with mental illness (9). Second, most mental health courts restrict their dockets to nonviolent misdemeanants, although at least one court (San Bernardino) hears felony cases and at least one (Broward County), with the victim's consent, hears cases of individuals charged with assault. Third, the courts all attempt to obtain quick access to community treatment services as an alternative to incarceration for individuals who appear before them.

To provide additional information about the organization and operation of mental health courts that have begun since, we conducted a survey of four additional mental health courts. We were particularly interested in the ways in which mental health courts use leverage over the disposition of the criminal charge as a tool to achieve compliance with community treatment and the extent to which sanctions, particularly jail, are used for nonadherence to court-ordered treatment. The use of penalties is a common feature of drug courts. Proponents of drug courts attribute much of their perceived success in retaining people in treatment and reducing criminal recidivism to a carrot-and-stick approach (10). We were interested in how mental health courts address this issue.

We report the results of our survey and compare the four courts we surveyed to the four described by Goldkamp and Irons-Guynn. We pay particular attention to the use of the leverages and sanctions used to encourage defendants to participate in treatment as an alternative to incarceration. We also suggest factors that might be considered by courts, treatment providers, advocates, and policy makers in addressing the role of sanctions within a mental health court. This is the first study to consider the use of sanctions by mental health courts; our purpose is not to provide outcome data but to describe the operations of these courts and to draw attention to this important policy issue.

Methods

The National GAINS Center for Persons With Co-Occurring Disorders in the Justice System estimates that about 29 mental health courts are currently operating in the United States (personal communication, Case B, Feb 19, 2002). In the summer of 2000 we identified the four longest-running mental health courts other than those studied by Goldkamp and Irons-Guynn: Santa Barbara, California; Clark County (Vancouver), Washington; Seattle, Washington; and Marion County (Indianapolis), Indiana. A staff member of each of the four courts, in some cases the presiding judge, was interviewed for one to two hours by telephone. Each was asked to provide the same information, which included a description of the defining features of their court as used by Goldkamp and Irons-Guynn in their research. Special attention was given to eliciting details on the disposition of criminal charges and use of sanctions to encourage treatment participation. Each interviewee was later asked to review the written summary of defining features of their court to ensure accuracy. Information about the four mental health courts described in the Goldkamp and Irons-Guynn study was adapted from their "Descriptive Summary" table and expanded on the basis of the text of their monograph and other supporting sources.

Results

Eligibility and identification of cases

Of the eight courts, all but one focuses primarily on misdemeanor cases. Each court requires mental illness as a threshold issue for admission to the mental health court program. Three of the courts include defendants with developmental disabilities. All of the courts acknowledge the high rate of co-occurring substance use disorders among defendants with serious mental illness and do not exclude defendants with such disorders.

Each court identifies possible participants within the first 24 to 48 hours of arrest, although the actual review process may take longer. In six courts, the court makes the eligibility determination with the input of a court team, usually made up of clinicians. In the other two courts, the prosecutor ultimately determines eligibility.

Disposal of the criminal charge

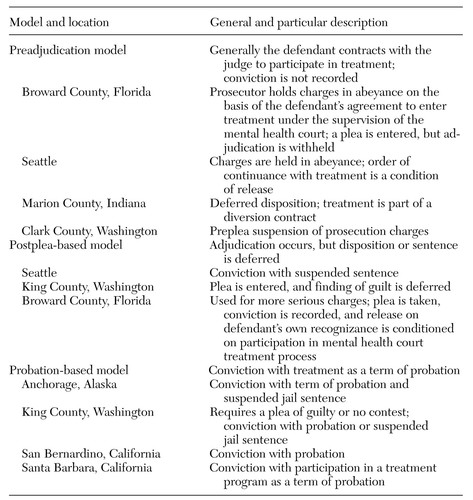

Table 1 summarizes the use of criminal charges by the eight mental health courts to mandate participation in treatment. In none of the eight are criminal charges immediately dropped when a defendant voluntarily agrees to participate in the mental health court. Most of the courts have more than one option for handling the criminal charges to mandate treatment participation, although in the majority of cases, one approach is used.

The Marion County, Seattle, and Broward County courts emphasize preadjudication mechanisms for disposition of charges, whereas the other five courts require guilty pleas for program entry. Clark County uses preadjudication methods for City of Vancouver cases but requires a guilty plea for the few cases it hears from outside the City of Vancouver because of county prosecutor preferences. Santa Barbara began with a preadjudication approach but has shifted to greater emphasis on a postplea approach, as preferred by the prosecutor, resulting in more recruitment into their mental health court.

Preadjudication, postplea, and probation-based legal statuses in the mental health courts determine how charges are disposed of during and after the end of the mental health courts' jurisdiction. In preplea cases, prosecution is generally deferred and charges are dismissed after successful completion of treatment. Adjudication occurs in postplea cases, but the sentence is deferred. Probation-based cases include a conviction with probation and sometimes a suspended or deferred jail sentence.

Many of the courts use dismissal of charges after successful completion of the mental health court program as an incentive to participate in community treatment and avoid reoffenses. Clark County allows the plea to be withdrawn and charges dismissed. Broward County, King County, and Anchorage give credit for time served, and the conviction may remain on the record, depending on the court.

In Seattle, the case concludes with the conviction remaining on record. Santa Barbara may terminate probation early or dismiss the probation violation. San Bernardino dismisses charges, and the defendant may petition for expungement. It is common for the courts to note in some fashion, such as a congratulatory announcement by the judge in open court, that the person has successfully completed the requirements established by the mental health court.

Supervision and sanctions

Schedules for court review of individual participants' progress vary. Seattle and Anchorage hold status review hearings as needed, depending on the participants' needs, compliance, and stability. Marion County reviews every month. Broward County and King County review at regular intervals and as needed. Participants in San Bernardino are seen every three to four weeks. Clark County and Santa Barbara see participants weekly and then less frequently if they are stable. Schedules for court review are driven more by limited court resources than by the optimal frequency of review.

Among the eight courts, three models are used for supervision in the community. The first uses existing community treatment providers, with reports back to the court when there are difficulties (Broward County, Anchorage, and most Clark County cases) or on a regular basis (Marion County). The second model uses staff from the mental health court or the probation or parole office to monitor care in the community (Seattle's specialized mental health probation officers, King County's probation officers, and Anchorage's Jail Alternative Services Project caseworker). The third model (San Bernardino and Santa Barbara) teams probation and mental health staff.

The courts differ in their use of sanctions. Only one court, which targets felony cases, reported frequently using jail as a sanction. Six of the courts reported rarely using jail. Other sanctions include returning the person to court for hearings, reprimands, and admonishments as well as stricter treatment conditions and changes in housing. San Bernardino is unique in its use of community service as a sanction. The courts do not keep specific records of the number of times various sanctions are used by the courts.

For most courts, the duration of mental health treatment and court supervision is determined by the state's maximum sentence allowed for misdemeanors—one year in the case of Broward County and Marion County and two years in the case of King County, Seattle, San Bernardino, and Clark County. The duration of court-supervised mental health treatment in Anchorage typically lasts from three to five years, because misdemeanor probation may be as long as ten years. San Bernardino has a fixed duration of three years for felony cases. Santa Barbara has a fixed duration of 18 months for all cases. The Marion County court can stay its jurisdiction when a participant undergoes psychiatric hospitalization or while a local criminal court handles new charges.

Discussion and conclusions

The goal of this study was to enhance our understanding of the operations of mental health courts, especially the disposition of criminal charges, by assessing whether four more recently established courts were similar to those described by Goldkamp and Irons-Guynn (8). In addition, we considered the use of sanctions by mental health courts, a procedure often used in drug courts but subject to considerable variation in mental health courts. To understand the phenomenon of mental health courts, it is essential to recognize that they are criminal courts. Any leverage they exert is likely to involve criminal sanctions unless charges are dropped—which rarely occurs.

We found that the more recently developed mental health courts focused on misdemeanants with mental illness, as did those described by Goldkamp and Irons-Guynn. Each sought quick access to community services, and each court was a specialty court with a docket dedicated to mental health cases. These similarities suggest that while it would be premature to characterize any mental health court as "typical," certain core characteristics are beginning to emerge.

At the same time, we saw differences in how the courts dealt with the criminal charge against the individual. Some required a plea of guilty for entry to the court, whereas others permitted the charge to be held in abeyance while the individual was under the court's jurisdiction. Whether the manner in which the court disposes of the criminal charge affects treatment adherence is a question worthy of future research.

All but one of the courts reported using jail sparingly if at all. This is an important difference between mental health courts and drug courts. The use of punishment is considered a core feature of drug courts and is used routinely in that setting (10). Sanctions are intended to increase retention in drug treatment, because, as Maxwell (11) has noted, retention in treatment has been found to be the only consistent predictor of successful outcome after release from treatment. In other words, offenders in drug treatment programs who stay in treatment longer are more likely to abstain from drugs and criminal behavior and to gain employment than those who participate in treatment for shorter periods.

The apparent reluctance to use punishment in mental health courts may stem from several factors. First, mental health courts focus generally on misdemeanors, whereas drug courts handle felonies. Some mental health court judges may believe that jail is unwarranted in a misdemeanor case in which public safety is not an issue. Second, there may be ambivalence in the justice system about imposing punishment if the perceived cause of the criminal behavior is mental illness. The law in general is not designed to punish people with serious mental illnesses and relies, in at least some cases, on competency adjudications and the insanity defense to ensure that this does not occur. Judicial attitudes toward mental illness may play a role in some mental health courts in deciding whether to use punishment, particularly jail.

In addition, there may be perceived differences in the impact that certain types of sanctions will have on people who have mental illnesses compared with people who have diagnoses of substance use disorders. For example, the presiding judge in San Bernardino has noted that sanctions must be individualized for mental health court participants, who may respond to sanctions differently than participants in a drug court (personal communication, Morris P, May 2001). He reported that weekend jail time motivated drug court participants to adhere to treatment conditions, whereas most mental health court participants were not averse to jail time but instead used that time as an opportunity to catch up on their sleep in a structured, predictable environment. As a result, the judge substituted community service as a sanction and found that it was more motivating for mental health court participants.

Although sanctions have apparently been used sparingly to date in mental health courts, expanded use may be anticipated as more mental health courts develop and as they begin to consider exercising jurisdiction over some types of felonies. Research on the use and impact of sanctions is important, as is research on strategies mental health courts can use to facilitate adherence to treatment without overreliance on court orders and punitive sanctions. For instance, could gaining quicker access to community treatment (12) be a positive influence on adherence to treatment and long-term avoidance of involvement with the criminal justice system? If so, mental health court programs that identify potential recipients shortly after arrest and release them to the community promptly may have more positive outcomes than courts that identify a defendant early but spend more time on evaluating the person, developing community treatment plans, and gaining sequential approvals from the various court actors before release to the community.

Does treatment adherence differ for mental health court participants who are not required to plead guilty but instead are given a preadjudication deferred-prosecution arrangement with release to the community contingent on completing treatment under court supervision? Do public defenders advise their clients differently depending on differences in the disposition of criminal charges and sanctioning options? Do linkages to existing community treatment resources that require the community system to more aggressively work with this population show better long-term outcomes than linkages to dedicated mental health court community treatment services that end when the court jurisdiction ends? Do community supervision approaches that combine probation and mental health staff result in more successful outcomes for mental health court participants than looser supervision arrangements? These critical questions about strategies for treatment adherence and reducing criminal recidivism will be understood only with continued empirical research examining the operation of mental health courts and the outcomes they obtain.

Finally, future research addressing mental health courts' mandating of treatment adherence should address both the use of criminal justice "hammers," such as varying sanctions and dispositions of criminal charges, and less coercive factors that may equally or more effectively facilitate adherence to treatment. Although mental health courts have been developed with the express intent of bringing to bear the force of the criminal justice system to mandate adherence to treatment, judges and other mental health court staff are deeply interested in nonpunitive ways to divert people with mental illness from the criminal justice system and into more productive community lives. One hallmark of existing mental health courts is how the criminal justice system in each locality has forged new alliances and cooperative relationships with mental health and social service systems to increase access to treatment for this population (8). Further research on the potential coercive nature of mental health courts should also examine the benefits of these partnerships for individuals with mental illness who are involved with the criminal justice system.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation's Initiative on Mandated Community Treatment and by the National GAINS Center for Persons with Co-Occurring Disorders in the Justice System, which is funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and operated by Policy Research Associates.

>Dr. Griffin is affiliated with the National GAINS Center for People With Co-Occurring Disorders in the Justice System, 8503 Flourtown Avenue, Wyndmoor, Pennsylvania 19038 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Steadman is with Policy Research Associates, Inc., in Delmar, New York, and Mr. Petrila is with the department of mental health law and policy of the Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute at the University of South Florida in Tampa.

|

Table 1. Three models used among eight mental health courts for using criminal charges to mandate participation in community treatment

1. National Alliance for the Mentally Ill: The Criminalization of People With Mental Illness. Available at www.nami.org/update/unitedcriminal.htmlGoogle Scholar

2. National GAINS Center for People With Co-Occurring Disorders in the Justice System: The prevalence of co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders in jail. Delmar, New York, National GAINS Center Fact Sheet Series, 2002Google Scholar

3. Watson A, Hanrahan P, Luchins D, et al: Mental health courts and the complex issue of mentally ill offenders. Psychiatric Services 52:477-481, 2001Link, Google Scholar

4. Cayce JD, Burrell K: King County's mental health court: an innovative approach for coordinating justice services. Washington State Bar News, June 1999, pp 19-23Google Scholar

5. Lerner-Wren G: Broward's mental health court: an innovative approach to the mentally disabled in the criminal justice system. Community Mental Health Report, November-December 2000, pp 5-6Google Scholar

6. Linden D: The mentally ill offender: a comprehensive community approach. American Jails, January-February 2000, pp 57-59Google Scholar

7. Petrila J, Poythress N, McGaha A, et al: Preliminary observations from an evaluation of the Broward County Mental Health Court. Court Review 37:14-22, 2001Google Scholar

8. Goldkamp JD, Irons-Guynn C: Emerging Judicial Strategies for the Mentally Ill in the Criminal Caseload: Mental Health Courts in Fort Lauderdale, Seattle, San Bernardino, and Anchorage. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance Monograph, pub no NCJ 182504, April 2000Google Scholar

9. Steadman HJ, Davidson S, Brown C: Mental health courts: their promise and unanswered questions. Psychiatric Services 52:457-458, 2001Link, Google Scholar

10. National Drug Court Institute: The critical need for jail as a sanction in the drug court model. Drug Court Practitioner Fact Sheet, vol 2, no 3. Alexandria, Virginia, National Drug Court Institute, June 2000Google Scholar

11. Maxwell S: Sanction threats in court-ordered programs: examining their effects on offenders mandated into drug treatment. Crime and Delinquency 46:542-563, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Gerstein D, Harwood H (eds): Treating Drug Problems: A Study of Evolution, Effectiveness, and Financing for Public and Private Drug Treatment Systems. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1990Google Scholar