Psychiatric Emergency Service Use and Homelessness, Mental Disorder, and Violence

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined relationships between homelessness, mental disorder, violence, and the use of psychiatric emergency services. To the authors' knowledge, this study is the first to examine these issues for all episodes of care in a psychiatric emergency service that serves an entire mental health system in a major city. METHODS: Archival databases were examined to gather data on all individuals (N=2,294) who were served between January 1, 1997, and June 30, 1997, in the county hospital's psychiatric emergency service in San Francisco, California. RESULTS: Homeless individuals accounted for approximately 30 percent of the episodes of service in the psychiatric emergency service and were more likely than other emergency service patients to have multiple episodes of service and to be hospitalized after the emergency department visit. Homelessness was associated with increased rates of co-occurring substance-related disorders and severe mental disorders. Eight percent of persons who were homeless had exhibited violent behavior in the two weeks before visiting the emergency service. CONCLUSIONS: Homeless individuals with mental disorders accounted for a large proportion of persons who received psychiatric emergency services in the community mental health system in the urban setting of this study. The co-occurrence of homelessness, mental disorder, substance abuse, and violence represents a complicated issue that will likely require coordination of multiple service delivery systems for successful intervention. These findings warrant consideration in public policy initiatives. Simply diverting individuals with these problems from the criminal justice system to the community mental health system may have limited impact unless a broader array of services can be brought to bear.

The President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health recognized as national priorities reducing homelessness and criminalization among persons with mental disorders (1). The commission also emphasized the need for evidence-based practice in improving mental health services. However, controversy exists about how to increase the availability and use of mental health services for individuals who are homeless and have mental disorders, especially when such individuals exhibit violent behavior (2).

Previous research has shown that homeless persons who have mental disorders and a history of criminal behavior tend not to use outpatient mental health services and emergency shelters (3). On the other hand, many have expressed concern that persons with mental disorders who are homeless are often inappropriately criminalized and that they should be taken to mental health treatment settings if they become dangerous (4,5,6,7). For example, the Treatment Advocacy Center has characterized as a "national disgrace" the fact that large numbers of persons with severe mental illness are currently untreated and has suggested that this lack of treatment is an important factor in their vulnerability to homelessness, episodes of violence, and incarceration (8). To assist in the development of informed policies intended to reduce homelessness and violence among persons with mental disorders and to ameliorate symptoms of mental disorders in subgroups of homeless persons who become violent, research is needed about current patterns of service use by such individuals.

The purpose of this study was to examine patterns of service use in the community mental health system in San Francisco by homeless persons with mental disorders who display violence. Other research has evaluated service use by this population in the criminal justice system (9). By describing patterns of service use in the community mental health system, we provide data relevant to public policy deliberations about strategies designed to divert persons with these problems from criminal justice settings to community treatment.

San Francisco's population is estimated to be approximately 776,700 (10). The San Francisco Mayor's Office on Housing estimated that there were about 12,500 homeless persons in San Francisco on any given night in 2000 (11).

Persons with mental disorders who are homeless and exhibit violent behavior that leads to a response from authorities in San Francisco are typically either brought to psychiatric emergency services for evaluation and possible hospitalization or arrested and brought to jail. This study retrospectively examined data for all such individuals during a six-month period in the psychiatric emergency service of the county hospital. We examined rates of homelessness, mental disorder, and violence; relationships between homelessness, mental disorder, and violence; and relationships between these variables and service use, as measured by episodes of psychiatric emergency service and psychiatric hospitalization. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine these issues for all episodes of service in a psychiatric emergency service that serves an entire major urban area.

Methods

The study involved retrospective review of computerized administrative databases from the component of the community mental health system in San Francisco that is responsible for evaluating and treating persons with mental disorders who present with behavioral emergencies. The committee on human research of the University of California, San Francisco, approved the study protocol. Because the project involved retrospective analysis of administrative data sets that did not identify individuals, the committee determined that informed consent was not necessary.

We retrospectively analyzed data for all episodes of service delivered to persons at least 18 years of age in the psychiatric emergency service at San Francisco General Hospital between January 1, 1997, and June 30, 1997. This psychiatric emergency service is the only one supported by the city and county of San Francisco and provides service to approximately 80 percent of individuals who are placed on emergency civil commitments in San Francisco. It provides service 24 hours per day, seven days per week; is the only facility in the county to directly accept involuntary patients petitioned for emergency civil commitment by the police; and was the only facility in the county to use the "crisis stabilization" billing code during the interval of this study.

Record of each episode of care

The record for each visit was coded for psychiatric diagnosis, whether the patient was homeless, age, gender, race or ethnicity, legal status, history of violence, and whether or not psychiatric hospitalization immediately followed the emergency department visit.

Mental disorder. Because patients can have more than one psychiatric diagnosis, we described the diagnostic characteristics of the patients according to the presence of each of the following diagnostic categories: substance-related disorders, schizophrenia, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, adjustment disorders, personality disorders, depressive disorders, and bipolar disorder, manic.

Homelessness. We operationally defined an individual as homeless if at the time of entry to the psychiatric emergency service the patient's living situation was recorded by the evaluating clinician as homeless, in transit, or in a shelter.

Violence. Descriptions of violent behavior by patients are routinely entered into the database of the psychiatric emergency service. We coded each record for the extent of violent behavior during the two weeks before entry to the emergency service, using a scale modeled on concepts used by the MacArthur Study of Mental Disorder and Violence (12). We operationally defined violence as a report of any act of physical aggression against other people, threatening others with a lethal weapon, or sexual assault within the two weeks before the emergency department visit.

Service use. We assessed all episodes of care in the psychiatric emergency service during the six months of the study and evaluated whether or not each episode of emergency service was immediately followed by psychiatric hospitalization. We also assessed the number of episodes of care in the psychiatric emergency service for each person.

To place the rates of homelessness among patients in the psychiatric emergency service in broader context, we also obtained summary information from the San Francisco Department of Public Health about rates of homelessness among the entire population of patients served by the San Francisco community mental health system during fiscal year 1996 through 1997.

Overview of data analysis

We examined rates of homelessness, mental disorder, and violence. We compared the demographic, clinical, and service use characteristics of patients who were and were not homeless with chi square analyses for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. These analyses used the episode of care, rather than the individual person, as the unit of analysis, because some individuals received multiple episodes of service. We also performed subsidiary analyses that used the individual person as the unit of analysis, to compare the number of episodes of service provided to homeless persons with the number provided to nonhomeless persons in the psychiatric emergency service. We analyzed the data by using SAS version 8.2 (13).

Results

Homelessness, violence, and mental disorder

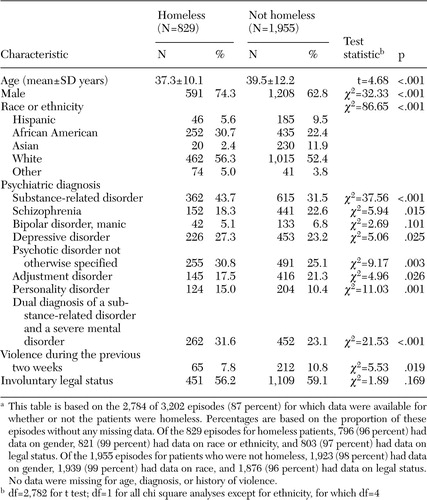

Rates among patients in the psychiatric emergency service. During the six months of the study, 2,294 different persons received 3,202 episodes of care in the psychiatric emergency service. The following results are based on the 2,784 of 3,202 episodes (87 percent) for which data were present for whether or not the patients were homeless. Table 1 shows that homeless patients used 829 of the 2,784 episodes of care (30 percent) in the psychiatric emergency service. The most common DSM-IV diagnosis was a substance-related disorder. A total of 977 episodes of service (35 percent) were provided to patients who had a substance-related disorder, which in almost all instances co-occurred with another mental disorder. Other frequently diagnosed conditions included psychotic disorders, mood disorders, adjustment disorders, and personality disorders. A total of 277 patients (10 percent) had a recent history of violent behavior.

Comparison of patients who were and were not homeless. Homeless patients were significantly more likely than other patients to be given a diagnosis of a substance-related disorder, personality disorder, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, and depressive disorder, and they were less likely than other patients to be given a diagnosis of schizophrenia and adjustment disorder. Homeless patients were more likely than other patients to have a dual diagnosis of a substance-related disorder and a severe mental disorder—that is, schizophrenia, psychotic disorder not otherwise specified, delusional disorder, depressive disorder, or bipolar disorder, manic.

Relationships between violence, diagnosis, and homelessness.Table 1 shows that the rate of violence in the two weeks before the emergency service visit was somewhat lower for homeless patients (8 percent) than for those who were not homeless (11 percent) (p<.02). Violence occurred somewhat more frequently among patients who were given a diagnosis of a severe mental disorder (227 of 2,132 episodes of service, or 11 percent) than among other patients (50 of 652 episodes of service, or 8 percent) (χ2=4.62, df=1, p<.04), an association that was observed whether or not a co-occurring substance-related disorder was present. Patients who were given a diagnosis of a substance-related disorder had somewhat lower rates of preadmission violence than other patients (80 of 977 episodes of service, or 8 percent, compared with 197 of 1,807 episodes of service, or 11 percent; χ2=4.91, df=1, p<.03). Additional analyses did not show significant interactions between homelessness, severe mental disorders, and co-occurring substance-related disorders in their association with violence.

Comparison with the entire community mental health system. Homeless patients were somewhat less likely to have a recent history of violence than other patients in the component of the community mental health system represented by the psychiatric emergency service. However, it must be recognized that homeless patients represent only a small proportion of the overall population who receive services in the community mental health system, yet they accounted for almost a third of the emergency department visits during the study period. To place these findings in broader context, we reviewed summary information about rates of homelessness in the entire population of patients served in the broader San Francisco community mental health system. According to the Department of Public Health, 1,577 patients were identified as homeless in fiscal year 1996 through 1997, or about 8 percent of the total community mental health caseload of 19,126. Given that 23 percent (65 of 277) of the episodes of psychiatric emergency service that were preceded by violence were by homeless persons, homeless individuals were approximately three times as likely as other patients with mental disorders who were served by the community mental health system to receive psychiatric emergency services after episodes of violence.

Homelessness and patterns of service use

Episode data. After an episode of emergency service use, homeless persons were more likely to be hospitalized than nonhomeless persons (χ2=10.61, df=1, p=.001). A total of 49 percent (401 of 829) of the emergency department visits by homeless patients were followed by hospital admission, compared with 42 percent (827 of 1,955) of visits by patients who were not homeless.

Individual person data. Additional analyses that used the individual person, rather than the episode of service use, as the unit of analysis showed elevated rates of emergency service use by homeless patients, particularly among those with co-occurring diagnoses of severe mental disorders and substance-related disorders. A total of 521 of the 1,915 individual persons (27 percent) for whom information about housing was available were homeless at the time of one or more emergency service visits. The proportion of patients who had more than one episode of service in the emergency department was largest among those who were homeless and had a dual diagnosis (99 of 191 patients, or 52 percent), followed by those who were not homeless and had a dual diagnosis (145 of 350 patients, or 41 percent), those who were homeless and did not have a dual diagnosis (70 of 330 patients, or 21 percent), and those who were not homeless and did not have a dual diagnosis (182 of 1,044 patients, or 17 percent) (χ2=153.68, df=3, p<.001).

Discussion

Homeless patients and emergency department visits

These findings show that patients who are homeless and have mental disorders represent a large proportion of those who used the most acute levels of care in the urban setting of this study. During the six months of this study, approximately 30 percent of the episodes of care in the psychiatric emergency service of the county hospital were provided to homeless patients. Homeless patients were more likely than other patients to have multiple episodes of emergency service use and to be hospitalized after receiving care in the emergency department. The burden on the acute care component of the community mental health system represented by the homeless population suggests that less intensive services are not meeting the needs of this group. Rather than being maintained in an ambulatory level of care, large numbers of homeless individuals are frequently cycling into the most acute levels of care. Such frequent episodes of crisis are likely associated with considerable human suffering and also consume expensive resources.

Homeless patients and co-occurring disorders

The elevated rates of co-occurring substance-related disorders and severe mental disorders among homeless patients seen in the psychiatric emergency service may provide clues about the mechanisms associated with the high level of emergency service use by this population. Past research in other settings has also reported elevated rates of substance-related disorders among homeless persons (14,15) and has found substance abuse to predict decreased adherence to community treatment among individuals with mental disorders (16). Because traditional systems of care tend to emphasize either mental health or substance abuse treatment services, the elevated rates of co-occurring substance abuse and severe mental disorders among homeless patients in the psychiatric emergency service may be an indication of insufficient and fragmented dual diagnosis services in the community for the needs of this population (17). It is possible that enhanced community treatment for dually diagnosed homeless patients could reduce their risk of relapse and reentry into psychiatric emergency services. Strategies such as harm reduction, motivational interviewing, and modified 12-step programs may be helpful with this population (18).

Homeless patients and violence

The rate of violence in the two weeks before emergency service use was somewhat lower among homeless patients compared with patients who were not homeless. However, it must be recognized that because entry into the psychiatric emergency service frequently is precipitated by behavioral disturbance, the comparison group of nonhomeless persons in the emergency service also had an elevated rate of behavioral dysfunction compared with the general population of psychiatric patients. Although only a small proportion of the population with mental disorders is homeless, the number of homeless persons who were violent before they received services in the psychiatric emergency service raises concern about an adverse impact on public safety when such individuals are in crisis. Homeless patients were three times as likely as others served by the broader community mental health system to receive psychiatric emergency services after episodes of violence.

These results are similar to another study that used a different method in New York City, which also reported increased rates of community violence by persons with mental disorders who were homeless (2). It is possible that violent behavior by homeless persons with mental disorders is more likely than such behavior by other persons with mental disorders to come to the attention of authorities because of its more public nature. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that addressing the service needs of this population could reduce the adverse impact on public safety posed by homeless persons with mental disorders who are undergoing behavioral emergencies.

Although this study focused on homelessness and considered the issue of violence more broadly, the data indicated that violent behavior was somewhat more likely to precede the emergency service visit for patients with severe mental disorders and somewhat less likely to precede the visit for patients with substance-related disorders. This finding differs from research with patients who have been stabilized in the hospital and then are followed up after discharge; among such patients the presence of co-occurring substance-related disorders has been found to be an important correlate of community violence (12,19,20,21). It is possible that patients with substance-related disorders are preferentially brought to jail if they display violence rather than to the emergency department. In addition, the rapid diagnostic assessments required in the emergency department may focus more on acute mental illness than on substance abuse and may have limited sensitivity in detecting co-occurring substance-related disorders.

Implications for public policy

At a policy level, our findings warrant consideration in the development of interventions designed to reduce the involvement of persons with mental disorders in the criminal justice system. Another study in San Francisco found that in a different six-month interval, psychiatric services were delivered during a comparable number of episodes of incarceration in the county jail (N=3,234) (9) as were delivered in episodes of care in the psychiatric emergency service (N=3,202) in the study reported here. Although it is clear that large numbers of persons with mental disorders are being brought to jail, the results of our study suggest that simply diverting these individuals to the community mental health system may have limited impact unless a broader array of services can be brought to bear. In our study homeless patients were high users of psychiatric emergency services, a pattern that suggests that many of them were not being stabilized but were undergoing a disproportionate number of crises relative to their proportion in the general population served by the community mental health system.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that interventions to address the co-occurring problems of homelessness, mental disorder, and violence need sufficient resources and coordinated involvement of multiple service delivery systems to be effective. Recent legislative and judicial adoption of mechanisms to leverage adherence to community treatment, such as outpatient civil commitment and mental health courts (22,23,24), may represent a component of the solution. However, without sufficient allocation of resources for comprehensive services that will address the complex needs of this population, such interventions are unlikely to be a panacea (25,26,27).

Our findings show that a substantial number of persons who have mental disorders and are high users of psychiatric emergency services are homeless. Such individuals have many problems in addition to poor adherence to community psychiatric treatment, such as co-occurring substance-related problems, poverty, a history of violent victimization, impoverished social networks, and co-occurring medical problems (14,28,29,30). Solutions to these complex problems will likely require substantial resources for intervening across multiple service delivery systems, in addition to encouraging adherence with community psychiatric treatment.

Previous research suggests that investment of resources in integrated service systems, assertive case management, supportive housing (with on-site medications, substance abuse services, and social services), community outreach and engagement, integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders, motivational interventions, and income support and entitlement assistance can be helpful for persons who are homeless and have mental disorders (31,32,33,34), although providing these services may not reduce overall expenditures (35). However, this investment of resources can be justified on other grounds, such as improvements in public safety, reduction in human suffering among persons who are homeless and have mental disorders, and improvement in community quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mark Leary, M.D., Richard Juster, Ph.D., Amanda Gregory, Ph.D., Judy Lam, Ph.D., Loretta Bolden, Fred McGregor, Karina Simonovich, and Paul Norris. This study was supported in part by a grant from the Psychiatric Foundation of Northern California.

Dr. McNiel is professor of clinical psychology and Dr. Binder is professor of psychiatry in the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, 401 Parnassus Avenue, San Francisco, California 94143-0984 (e-mail, [email protected]). Preliminary results were presented at the International, Interdisciplinary Conference on Psychology and Law—supported by the American Psychology-Law Society; the Australian and New Zealand Association of Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law; and the European Association of Psychology and Law—held July 9 to 12, 2003, in Edinburgh, Scotland.

|

Table 1. Characteristics associated with episodes of psychiatric emergency service use, by patients who were and were not homeless (N=2,784)a

aThis table is based on the 2,784 of 3,202 episodes (87 percent) for which data were available for whether or not the patients were homeless. Percentages are based on the proportion of these episodes without any missing data. Of the 829 episodes for homel

1. New Freedom Commission on Mental Health: Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. DHHS pub no SMA-03–3823. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003Google Scholar

2. Martell DA, Rosner R, Harmon RB: Base rate estimates of criminal behavior by homeless mentally ill persons in New York City. Psychiatric Services 46:596–601,1995Link, Google Scholar

3. Gelberg L, Linn LS, Leak BD: Mental health, alcohol and drug use, and criminal history among homeless adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:191–196,1988Link, Google Scholar

4. Quanbeck C, Fry M, Altshuler L: Mania and the law in California: understanding the criminalization of the mentally ill. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1245–1250,2003Link, Google Scholar

5. Torrey EF: Out of the Shadows: Confronting America's Mental Illness Crisis. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

6. Lamb HR: Will we save the homeless mentally ill? American Journal of Psychiatry 147:649–651,1990Google Scholar

7. Belcher JR: Are jails replacing the mental health system for the homeless mentally ill? Community Mental Health Journal 24:185–195,1988Google Scholar

8. Fact Sheet: Homelessness, Incarceration, Episodes of Violence: Way of Life for Almost Half of Americans With Untreated Severe Mental Illness. Treatment Advocacy Center, 2003 Available at www.psychlaws.org/generalresources/fact2.htmGoogle Scholar

9. McNiel DE, Binder RL, Robinson JL: Incarceration associated with homelessness, mental disorder, and co-occurring substance abuse. Psychiatric Services, in pressGoogle Scholar

10. Census 2000. US Census Bureau. Available at www.census.govGoogle Scholar

11. 2000 Consolidated Plan. San Francisco Mayor's Office on Housing. Available at www.sfgov.org/site/moh_index.asp?id=5816Google Scholar

12. Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Silver E, et al: Rethinking Risk Assessment: The MacArthur Study of Mental Disorder and Violence. New York, Oxford, 2001Google Scholar

13. SAS Version 8.2. SAS Institute. Cary, NC, 2001Google Scholar

14. Drake RE, Wallach MA: Homelessness and mental illness: a story of failure. Psychiatric Services 50:589,1999Link, Google Scholar

15. Salkow K, Fichter M: Homelessness and mental illness. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 16:467–471,2003Google Scholar

16. Binder RL, McNiel DE, Sandberg DA: A naturalistic study of clinical use of risperidone. Psychiatric Services 49:524–526,1998Link, Google Scholar

17. Rosenheck RA. Resnick SG, Morissey JP: Closing service system gaps for homeless clients with a dual diagnosis: integrated teams and interagency cooperation. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 6:77–87,2003Medline, Google Scholar

18. RachBeisel J, Scott J, Dixon L: Co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders: a review of recent research. Psychiatric Services 50:1427–1434,1999Link, Google Scholar

19. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE: Persons with severe mere mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatric Services 49:483–492,1998Link, Google Scholar

20. McNiel DE, Borum R, Douglas KS, et al: Risk assessment, in Taking Psychology and Law into the Twenty-first Century. Edited by Ogloff JRP. New York, Kluwer Academic/Plenum, 2002Google Scholar

21. McNiel DE: Empirically based clinical evaluation and management of the potentially violent patient, in Emergencies in Mental Health Practice: Evaluation and Management. Edited by Kleespies PM. New York, Guilford, 1998Google Scholar

22. Monahan J, Schwarz M: Special section on involuntary outpatient commitment: introduction. Psychiatric Services 52:323–324,2001Link, Google Scholar

23. Compton SN, Swanson JW, Wagner HR, et al: Involuntary outpatient commitment and homelessness in persons with severe mental illness. Mental Health Services Research 5:27–38,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Steadman HJ, Davidson MA, Brown C: Mental health courts: their promise and unanswered questions. Psychiatric Services 52:457–458,2001Link, Google Scholar

25. Appelbaum PS: Ambivalence codified: California's new outpatient commitment statute. Psychiatric Services 54:26–28,2003Link, Google Scholar

26. Petrila J, Ridgely MA, Borum R: Debating outpatient commitment: controversy, trends, and empirical data. Crime and Delinquency 49:157–172,2003Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Goin MK: The Commission's report and its implications for psychiatry. Psychiatric Services 54:1480–1481,2003Link, Google Scholar

28. Draine J, Salzer MS, Culhane DP, et al: Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:565–573,2002Link, Google Scholar

29. McQuistion HL, Finnerty M, Hirschowitz J, et al: Challenges for psychiatry in serving homeless people with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Services 54:669–676,2003Link, Google Scholar

30. Salit SA, Kuhn EM, Hartz AJ, et al: Hospitalization costs associated with homelessness in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine 338:1734–1740,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Blueprint for Change: Ending Chronic Homelessness for Persons With Serious Mental Illness and Co-Occurring Substance Use Disorders. DHHS pub no SMA-04–3870, Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, 2003Google Scholar

32. Dvoskin JA, Steadman HJ: Using intensive case management to reduce violence by mentally ill persons in the community. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:679–684,1994Abstract, Google Scholar

33. Gonzalez G, Rosenheck RA: Outcomes and service use among homeless persons with serious mental illness and substance abuse. Psychiatric Services 53:437–446,2002Link, Google Scholar

34. McGuire JF, Rosenheck RA: Criminal history as a prognostic indicator in the treatment of homelessness people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:42–48,2004Link, Google Scholar

35. McGuire J, Rosenheck RA, Kasprow WJ: Health status, service use, and costs among veterans receiving outreach services in jail and community settings. Psychiatric Services 54:201–207,2003Link, Google Scholar