Rehab Rounds: Psychiatric Rehabilitation in a Chinese Psychiatric Hospital

Introduction by the column editor: This month's column may surprise readers who have a slanted view of Chinese psychiatry as being misused for political purposes. In actuality, treatment of people with serious mental illness in China has made great strides in the past two decades as methods used in Western societies have been avidly adapted by clinicians in major Chinese cities. In 1993, I conducted a two-week workshop in Beijing on psychiatric rehabilitation for psychiatrists from throughout China (1). In subsequent visits I was impressed by the fidelity with which Chinese psychiatrists conducted social skills training. Although most psychiatric services in China are still delivered in large hospitals, the following report from Beijing documents that positive outcomes for community reintegration are possible in large institutions.

Chinese patients with schizophrenia experience the same repeated relapses and rehospitalizations, disability, and poor quality of life as their counterparts in the United States. In addition, Chinese culture casts extraordinarily high levels of stigma on people with mental illness, which raises serious barriers to these individuals' reintegration into family and community life. The mentally ill in China are treated in large, long-stay psychiatric hospitals where treatments include active and passive music therapy, exercise, and horticulture therapy. Only recently have community-based services become available. At An-Ding Hospital in Beijing, which is affiliated with the Capital University of Medical Sciences, a controlled study was carried out to compare a multimodal approach to treatment and rehabilitation of inpatients with schizophrenia with treatment as usual.

Methods

Patients and setting

An-Ding Hospital contains 16 wards that serve as many as 867 patients at any one time. During the 18-month study period in 2002-2003, a total of 635 patients who had been given a provisional diagnosis of schizophrenia were admitted to the hospital. Patients were excluded from the study if they did not meet the DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia, had concurrent mental retardation, did not have a family member who agreed to provide housing for the patient after discharge, suffered from severe physical disease, lacked education beyond the sixth grade, or did not give informed consent. A total of 124 patients met the entry criteria and were randomly assigned to a rehabilitation group or a control group.

At baseline, no significant differences between the two groups were noted on education, family history, employment history, marital status, illness course, or number or duration of past hospitalizations. Types and dosages of antipsychotic medications were prescribed on a doctor's-choice basis, and the medications were administered by nursing staff. Attrition was minimal; 61 patients in each group were successfully followed up one year after discharge.

Rehabilitation program

The multimodal rehabilitation program was delivered in groups of eight to ten patients over the course of two months in the hospital. Treatment and rehabilitation were integrated by interdisciplinary teams and took place in four phases: control of psychotic symptoms by titration of medication and ward activities and social interactions with staff and other patients; improvement of social functioning through individualized social skills training (2) and prompting and reinforcement of patients' initiating and satisfactorily performing activities of daily living and social interaction, providing opportunities and encouragement for social interaction and relaxation for stress management; occupational therapy that was individualized for compatibility with patients' education, previous work experience, phase of illness, interests, preferences, and skills; and social integration during which patients participated in two educational programs, or modules, translated from those developed in California—one on medication management and one on symptom management (3).

The occupational therapy phase comprised a variety of work experiences, ranging from simple to more complex tasks: cleaning, sewing, packaging, welding, machine-based cutting of plastics and other materials, electrothermal sealing of packages, and caring for domesticated animals. Patients received social reinforcement and material rewards contingent on their showing progress in completing work tasks during this phase. The purpose of the social integration phase was for patients to learn and demonstrate use of disease management skills, leading to medication self-administration and a relapse-prevention plan.

The control group participated in standard inpatient services and activities: individualized medication linked to clinical response, encouragement to complete activities of daily living, milieu therapy, music therapy, occupational therapy involving arts and crafts, exercise classes, and discharge planning with the aid of a social worker. Patient-staff contact was considerably less for the patients in the control group than for those in the rehabilitation group.

Evaluation

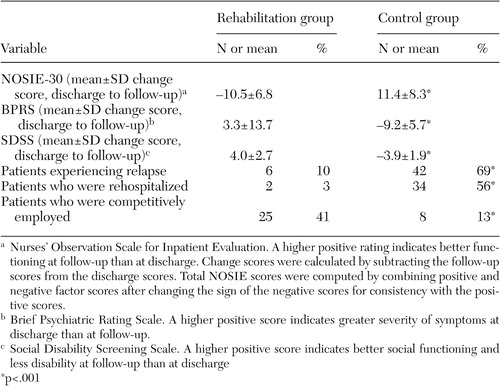

Double-blind assessments of patients in the two treatment conditions were carried out by a team of three psychiatrists and two senior nurses whose interrater agreement ranged from a kappa of .88 to a kappa of .97. Assessments were multidimensional and were conducted every two weeks during the hospital phase and monthly after discharge to the community. The results are shown in Table 1 for symptoms (measured with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale), social functioning (measured with the 30-item Nurses' Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation and the Social Disability Screening Scale), employment, psychotic relapse, and rehospitalization. The definition of employment was six months or more of work in the open marketplace in a factory, an office, or a store or public service work. In all six assessment domains, the patients in the rehabilitation group improved significantly more than their counterparts in the control group from baseline to discharge and from discharge to follow-up in the community (p<.001).

Conclusions

Because this study was carried out with ordinary clinical staff in a typical Chinese psychiatric hospital, it can be viewed as a study of effectiveness rather than efficacy. Although the social skills training methods that were used in the rehabilitation program were borrowed from those developed in the United States, they were adapted for acceptability and relevance in Chinese culture. For example, because of the importance of family cohesion and joint decision making in China, the key family members of patients were involved in some of the training sessions with patients when the topics were use of medication and an emergency plan for relapse prevention.

Relaxation for stress management was taught in the context of "passive" music therapy, wherein patients listen to music with headphones while rhythmic lights are projected onto the walls of the room.

Unlike in the United States, the number of psychiatric beds per capita is on the increase in China, and community-based services are extremely limited. It is our belief that active promotion of psychiatric rehabilitation in Chinese psychiatric hospitals at the present time will pave the way for large-scale implementation of community-based rehabilitation in the future.

Afterword by the column editor: Cross-cultural replication of psychiatric rehabilitation modalities represents a form of discriminant validity in which similar results are obtained in different countries. For example, favorable results with the medication management module have been replicated in a previous study in China (7). Although two months of inpatient treatment for acute schizophrenia is far more than that available in almost all American facilities, this variation also illustrates how local policies, conditions, staffing, and resources dictate the specific qualities of an intervention in effectiveness studies. It is notable that the results of this study in Beijing mirror those obtained with similar rehabilitation programs in other countries (4,5). The high rate of discharged patients with schizophrenia who secured employment in regular jobs parallels the benefits achieved by supported employment programs in the United States. This finding suggests that the mode and focus of rehabilitation are as important as the locus in regard to favorable outcomes for patients (6).

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by grant 2002-1021 from the Capital Foundation for Development of Medical Science in Beijing.

Dr. Weng and Dr. Xiang are affiliated with An-Ding Hospital and Capital University of Medical Sciences in Beijing. Dr. Liberman, who is editor of this column, is professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles, Neuropsychiatric Institute, 760 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, California 90095 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Results from a controlled clinical trial of a psychiatric rehabilitation program compared with customary treatment for Chinese inpatients with schizophrenia

1. Liberman RP: Treatment and rehabilitation of the seriously mentally ill in China: impressions of a society in transition. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 64:68–77, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Liberman RP, DeRisi WJ, Mueser K: Social Skills Training for Psychiatric Patients. Norwood, Mass, Allyn & Bacon, 1989Google Scholar

3. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Silverstein S: Psychiatric rehabilitation, in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 8th ed. Edited by Sadock BJ, Sadock V. Baltimore, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2004Google Scholar

4. Schaub A, Behrendt B, Brenner HD: A multi-hospital evaluation of the medication and symptom management modules in Germany and Switzerland. International Review of Psychiatry 10:42–46, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Anzai N, Yoneda S, Kumagai N, et al: Training persons with schizophrenia in illness self-management: a randomized controlled trial in Japan. Psychiatric Services 53:545–548, 2002Link, Google Scholar

6. Paul GL, Lentz R: Psychosocial Treatment of the Chronic Mental Patient. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1977Google Scholar

7. Xu Z, Weng Y, Hou Y: Efficacy and follow-up of medication management module training for schizophrenic patients in Beijing. Chinese Journal of Psychiatry 32:96–99, 1999Google Scholar