Economic Grand Rounds: Access to Psychiatrists in the Public Sector and in Managed Health Plans

Although the demand for psychiatric treatment has increased dramatically over the past decade, with the proportion of the population receiving treatment for depression alone more than tripling (1), the number of psychiatrists in the United States has plateaued and is expected to lag notably behind population growth (2). Also, during the past decade, both public- and private-sector payers have sought to constrain the costs and the use of mental health services while ideally increasing the quality of care.

There is evidence that the costs and use of mental health services have been constrained (3), and there is concern that access to psychiatric treatment in public and managed systems of care has been significantly reduced. The effect of this reduction on the quality of care has been largely unmeasured. One of the major concerns that has been raised about access to mental health services is that increased administrative burden, decreased fees, and limited treatment options will result in significantly decreased participation by psychiatrists in these publicly financed and managed health care plans. The aim of this study was to assess the extent to which psychiatrists are accepting new patients with different types of insurance (Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance) and with different types of care plans (managed and nonmanaged). Additionally, we identified psychiatrist variables and geographic regions that were strongly associated with accepting patients with public sources of insurance or with managed care plans.

Data collection

Psychiatrists in our study were participants in the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education's (APIRE's) Practice Research Network 2002 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice. A national sample of 2,323 U.S. psychiatrists was randomly selected from the American Medical Association's Masterfile of physicians (N=49,000). Data collection occurred between February and September 2002. Psychiatrists answered either paper or Web-based surveys; four survey waves were implemented to achieve the final response rate of 52 percent (N=1,203).

Data were collected on the overall characteristics of the psychiatrist's practice and patient caseload. Our analyses used responses from a question that asked, "Are you currently accepting any new patients from the following health plans/payment options?" Response options for this question were private insurance provided through a managed care panel, private insurance not provided through a managed care plan, Medicare, Medicaid, and self-pay. Psychiatrists were also asked for the number of managed care networks or physician panels on which they currently serve. The SUDAAN statistical package was used to analyze the data and generate nationally representative estimates (4).

Findings

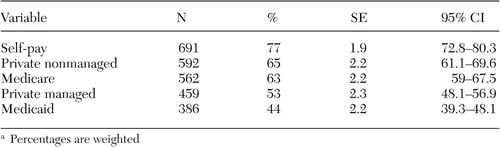

Overall, 85 percent of psychiatrists were willing to accept new patients. However, psychiatrists' willingness to accept new patients was significantly associated with the type of health plan to which the patient belonged or with the patient's payment option (Fisher exact test, p<.001). As Table 1 indicates, rates of acceptance of new patients varied significantly by health plan. Although most psychiatrists (77 percent) accepted patients who used self-pay, less than half (44 percent) accepted patients who used Medicaid. Sixty-five percent of psychiatrists surveyed accepted new patients who used unmanaged private insurance, whereas significantly fewer (53 percent) accepted new patients from managed private insurance plans. Only 48 percent of psychiatrists reported serving in any managed care network or on any physician panels; more than 25 percent of those who were in these networks or on these panels did not accept new patients from these networks or panels. Additionally, 63 percent of psychiatrists accepted new patients who used Medicare, a significantly higher percentage than those who accepted patients in either private managed insurance plans or Medicaid.

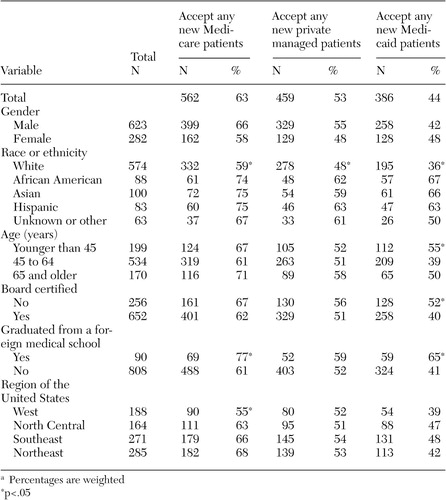

As shown in Table 2, several factors were significantly associated with accepting new patients with public sources of insurance or private managed insurance. Psychiatrists were significantly more likely to accept new patients with Medicaid if the psychiatrists were foreign medical school graduates, not board certified, nonwhite, and younger than 45 years. Psychiatrists were significantly more likely to accept new patients with Medicare if the psychiatrists were foreign medical school graduates, practiced in the western region of the United States, and were nonwhite. Psychiatrists were significantly more likely to accept new patients with private managed insurance plans if the psychiatrists were nonwhite.

Access to psychiatric care

The results of these analyses are troubling because they present evidence of limited access to psychiatrists, particularly among patients with Medicaid and with managed private insurance plans. This finding is particularly disconcerting because a majority of individuals with private insurance in the United States (70 percent) are enrolled in private managed plans (5) and because of trends in the psychiatry workforce. For example, as a whole, the psychiatry workforce is aging, working fewer hours, and spending less time in patient care (6). This finding suggests that the availability of psychiatric resources may continue to decline as the number of psychiatrists and the amount of their time spent in direct patient care continues to be restricted. Clearly, these trends suggest that access to psychiatric care may also decrease.

Additionally, lowered fees in the public mental health system and managed private insurance plans may be a major factor in the decreasing access to psychiatric treatment. For example, in 2002 the average discounted fee that psychiatrists received for 45 to 50 minutes of individual psychotherapy with medical evaluation and management (CPT code 90807) was $47.95 less than their average undiscounted fee of $155.59; differentials for Medicaid fees were even greater—for example, the Medi-Cal rate is currently $49.22 for CPT code 90807 (7,8). If state and federal budgets increasingly require the government to reduce funding for Medicaid and mental health benefits, as has been suggested (9), and private insurance further reduces coverage for mental health benefits, the problem of access to psychiatric care will be exacerbated.

In addition to these factors, preliminary findings from APIRE's 2000 Federal Employees Health Benefits Program Parity Evaluation indicate that psychiatrists and their staff face significant administrative burdens in health care plans that are privately managed, in Medicare, and in Medicaid (10). The study showed that psychiatrists and their staff in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area spent significantly more time performing administrative activities when they saw patients from private managed plans and Medicaid than when they saw patients from unmanaged plans. The study also found that the more time psychiatrists spent in administrative activities for a specific health plan, the less likely they were to recommend that plan to family members or colleagues. Consequently, it is likely that the number of psychiatrists willing to accept new patients is related to the level of management and fees associated with specific insurance programs. Alternatively, many managed care plans have a limited network of providers. Therefore, if psychiatrists do notaccept patientswith managed private insurance, it could be a reflection of their not being invited to join the managed care network, which may not be their choice.

Implications for mental health treatment

The limitations in access to psychiatrists among patients with managed private insurance and Medicaid have several implications for mental health treatment. Because psychiatrists are the primary providers of psychopharmacologic treatments in the mental health sector, access to psychopharmacologic treatments—which have become increasingly important in the treatment of mental disorders—is of particular concern. Reductions in the number of psychiatrists who accept new patients in an already declining workforce will likely be associated with delays in treatment and a potential decrease in quality of care. Delays in treatment are associated with substantial personal and economic costs related to increases in severity of mental illness and decreases in general health status (11,12).

An important question is whether other specialty mental health providers—for example, psychologists and social workers—are also constrained in their ability to accept new patients. Recent findings indicate that a significant proportion of patients with schizophrenia, major depression, and bipolar disorders who were seeing a psychiatrist were not receiving guideline-recommended psychosocial treatment from any provider, not just psychiatrists (13). This finding suggests that constrained access to specialty mental health providers could further exacerbate the problem of access to mental health treatment. Consequently, the current problem of gaining access to needed treatments does not appear to be limited to psychopharmacologic interventions alone. If patients do not have adequate access to psychiatrists and other mental health specialists, they are likely to get treatment, if they indeed receive treatment, from providers who do not work in the specialty mental health sector and who have less training in psychiatric interventions.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest a serious public health problem of access to psychiatric care in privately managed insurance plans and Medicaid, which are aggravated by other factors, such as declining fees, increasing administrative burden, and declining workforce numbers. These findings point toward a need for further research that will explore whether access to care is also limited among other mental health specialists. Although some factors that were associated with psychiatrists' accepting new patients are not modifiable, policy steps can be taken to address the problem of gaining access to care. Increased access may be achieved through increased federal support for clinical training in mental health professions and a decrease in the administrative and financial disincentives to participation in these health plans. If current trends in the psychiatric workforce and public and private reimbursement for mental health care are not reversed, the treatment access crisis will only worsen.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maritza Rubio-Stipec, Sc.D., for her helpful suggestions. Psychiatrists who participated in the APIRE 2002 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice contributed their time to participate in the study. Development and support of the PRN have been generously funded by the American Psychiatric Foundation, the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, the Center for Mental Health Services, and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

The authors are affiliated with the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education's Practice Research Network, 1000 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 1825, Arlington, Virginia 22209 (e-mail, [email protected]). Steven S. Sharfstein, M.D., and Haiden A. Huskamp, Ph.D., are editors of this column.

|

Table 1. Psychiatrists from the National Survey of Psychiatric Practice who accept new patients, by type of insurance and health plan (N=1,203)a

a Percentages are weighted

|

Table 2. Characteristics of 1,203 psychiatrists from the National Survey of Psychiatric Practice who accept new patientsa

a Percentages are weighted

1. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, et al: National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA 287:203–209, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Cooper RA: There's a shortage of specialists: is anyone listening? Academic Medicine 77:761–766, 2002Google Scholar

3. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R: Costs and use of mental health services before and after managed care. Health Affairs 17(2):40–52, 1998Google Scholar

4. Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Hunt PN, et al: SUDAAN user's manual, release 7.0. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1996Google Scholar

5. Scheffler RM: Managed behavioral health care and supply-side economics. 1998 Carl Taube Lecture. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 2:21–28, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Scully JA, Wilk JE: Selected characteristics and data of psychiatrists in the United States 2001–2002. Academic Psychiatry 27:247–251, 2004Crossref, Google Scholar

7. West JC, Wilk JE, Rae DS, et al: Financial disincentives for the provision of psychotherapy. Psychiatric Services 54:1582–1588, 2003Link, Google Scholar

8. Hunt S, Maerki S, Tompkins R: Comparing CPT Code Payments for Medi-Cal and Other California Payers. Oakland, Medi-Cal Policy Institute, 2001Google Scholar

9. Boyd DJ: The bursting state fiscal bubble and state Medicaid budgets. Health Affairs 22(1):46–61, 2003Google Scholar

10. Preliminary study findings from the 2000 parity evaluation study. PRN Update, spring, 2002Google Scholar

11. Katzelnick DJ, Simon GE, Pearson SD, et al: Randomized trial of a depression management program in high utilizers of medical care. Archives of Family Medicine 9:345–351, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Berndt ER, Koran LM, Finkelstein SN, et al: Lost human capital from early-onset chronic depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:940–947, 2000Link, Google Scholar

13. New Findings From the PRN Document Limited Access to Psychotherapy and Financing Barriers. PRN Update, spring 2003Google Scholar