Brief Reports: Hopelessness as a Predictor of Work Functioning Among Patients With Schizophrenia

Abstract

Although many persons with schizophrenia report significant levels of hopelessness, less is understood about the impact of hopelessness on functioning. This study examined the relationship between initial ratings of hopelessness and work functioning in the third week of a vocational rehabilitation program for 34 veterans with a diagnosis of a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder. Pearson correlations revealed that poorer task performance was associated with perhaps unrealistic expectations of success, whereas poorer interpersonal functioning at work was associated with poorer motivation. The findings suggest that specific domains of hopelessness are associated with different aspects of work functioning.

As with many medical conditions, dysfunctional beliefs and associated painful affects are commonly found among persons with schizophrenia. These beliefs include perceptions of oneself as disempowered, expectations of future disappointment, and a belief that the future cannot be influenced by any amount of present effort (1). Beyond being a potent source of distress, such hopelessness may result in ineffectual coping, demoralization, and a poor quality of life (2,3).

Although hopelessness associated with schizophrenia has been linked to psychosocial dysfunction in general and to work outcomes in particular (4), it is less clear what specific aspects of interpersonal and instrumental functioning at work are linked to hopelessness. Accordingly, we tested two competing hypotheses about the relationship of hopelessness to task performance and interpersonal functioning in a vocational rehabilitation program. The first hypothesis was that, in the absence of hope, persons with schizophrenia would withdraw from others at work, respond to problems on the job with a defeatist attitude, and, accordingly, manifest poorer work performance. The alternative hypothesis was that persons with the highest levels of hope might be ill prepared to face setbacks, resulting in poorer responses to problems and, consequently, poorer work performance. In other words, consistent with literature on "depressive realism" (5), it is possible that persons with the lowest levels of hope are the most realistic and are more likely to succeed.

To test these two hypotheses, we examined whether the three domains of hopelessness measured by the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) (6) were prospectively related to work functioning in the third week of vocational rehabilitation. Because research has indicated that poorer neurocognition as measured by the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) (7) may predict higher levels of hope among persons with schizophrenia (3), we included WCST score as a covariate to rule out the possibility of its accounting for the observed relationships.

Methods

Thirty-four participants were recruited from a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center outpatient service for an ongoing study of the effects of work rehabilitation among persons with schizophrenia. The study was conducted from November 2001 through April 2003. The participants were in a postacute phase of disorder, defined as having experienced no hospitalizations or changes in housing or psychiatric medications in the previous month. Exclusion criteria were evidence of organic brain syndrome or mental retardation.

After approval had been received from the medical center's institutional review board and informed consent had been obtained, a clinical psychologist administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (8) to establish whether participants met the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Next, participants completed the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS) (6), a questionnaire asking participants to indicate whether statements about the future applied to them. Individual items were summed to provide scores for three factors representing semi-independent domains of hopelessness: feelings about the future, loss of motivation, and future expectations. Finally, participants completed the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (7), a neuropsychological test that is sensitive to impairments in executive functioning. The test requires participants to sort cards that vary according to shape, color, and number of objects depicted. Participants are told to match cards to "key" cards but are not told the matching principle, which changes periodically. This study used the age- and education-corrected t score for percent perseverative responses, which is hypothesized to indicate inflexibility of abstract reasoning. Perseverative responses are responses in which participants fail to shift set.

Participants then entered a work therapy program that included an entry-level job placement at the medical center consistent with their interests for $3.50 an hour, up to 20 hours a week. Participants worked alongside regular hospital employees in areas such as laundry, customer service, and grounds maintenance. During the third week of work, a trained rater measured the participant's work behaviors by using the Work Behavior Inventory (WBI) (9) after direct observation and an interview with the person's work supervisor. This inventory produces five indexes of work behavior: two indexes of task performance (work quality and work habits) and three indexes of interpersonal functioning (social skills, cooperativeness, and personal presentation). Interrater reliability was assessed, and intraclass correlations were found to range from good to excellent (.79 to .96). We chose to assess work behaviors during the third week on the basis of previous research indicating that by the third week more enduring patterns of work behavior have emerged (10).

Results

The sample was primarily male (33 participants, or 97 percent). Nineteen participants (56 percent) were Caucasian, and 15 (44 percent) were African American. The average age of the participants was 46±7 years, and the average level of education was 12±1 years. The participants had an average of 10±9 previous psychiatric hospitalizations, the first occurring at an average age of 25±8 years. Nineteen participants (56 percent) met the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, and 15 (44 percent) met the criteria for schizoaffective disorder.

Mean±SD baseline scores on the three factors of the BHS were 3.7±1.7 for feelings about the future (possible scores range from 0 to 5), 5.9±2.7 for loss of motivation (possible scores range from 0 to 8), and 2.5±1.6 for future expectations (possible scores range from 0 to 5). Higher scores indicate more hope. Mean baseline scores on the five indexes of the WBI were 3.2±.46 for work quality, 3.3±.52 for work habits, 3.2±.49 for social skills, 3.3±.35 for cooperativeness, and 3.2±.39 for personal presentation. Each of the 35 WBI items is rated on a scale ranging from 1, a persistent problem area, to 5, a frequent area of strength.

Pearson correlations revealed that BHS scores were significantly related to one another, with r values ranging from .79 to .82. WBI scores were also positively intercorrelated, with r values ranging from .38 to .83. Age, education, and diagnosis were unrelated to BHS and WBI scores. Participants worked a mean of 17.1±3.88 hours during week 3.

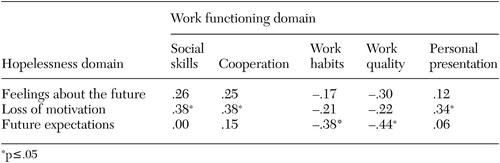

To examine the associations between hopelessness and work functioning, we examined correlations between the BHS scores and the five WBI indexes. As can be seen from Table 1, greater expectations of success were significantly related to poorer task performance. Loss of motivation was related to poorer interpersonal functioning at work. When we repeated the correlation analysis with the percent perseverative responses t score from the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test as a covariate, the correlations were still significant. This finding indicates that the results are independent of an aspect of cognitive functioning that was correlated with hopelessness in previous research.

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study suggest that some forms of hopelessness are, paradoxically, related to better work functioning, whereas other forms are related to poorer functioning. In particular, despite positive intercorrelations among the BHS scales, persons with higher expectations of success—that is, those who reported that they were more hopeful about finding satisfaction in the future—tended to have poorer work habits and to produce work of lesser quality. Yet persons with lower motivational hope—that is, those who reported that they were more likely to give up than to persist—tended to have poorer social skills and to cooperate less with others at work.

One possible explanation for this paradox is that different levels of different domains of hopefulness are related to optimal functioning. Consistent with literature on anticipatory anxiety is the possibility that some expectations of failure—or low to moderate expectations of success—are necessary to mobilize effective coping, resulting in better task performance at work. However, a moderate to high expectation that one will persist despite adversity is necessary for persons to interact effectively and work comfortably alongside others.

Of note, the generalizability of the findings of this study is limited by the fact that the sample was small and was composed primarily of middle-aged male veterans. Further research is needed if we are to understand how levels and domains of hopelessness may operate on a continuum from supporting to interfering with optimal work functioning among persons with schizophrenia and to determine whether there is a differential pattern of association between hope and different aspects of work functioning. Nevertheless, the findings of this study provide some evidence linking cognitions to work outcome among persons with schizophrenia. If our data are replicated in larger and more diverse samples, they may provide a basis for interventions directed at assisting persons with schizophrenia who enter work with differing hopelessness profiles to perform successfully at work.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Rehabilitation, Research, and Development Service of the Department of Veteran Affairs.

All authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of Roudebush Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Indianapolis. Dr. Lysaker is also with the School of Medicine at Indiana University in Indianapolis. Send correspondence to Dr. Davis at Psychiatry Research 116A, Roudebush VA Medical Center, 1481 West Tenth Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Pearson correlations between hopelessness domains and work functioning domains among 34 veterans with schizophrenia who participated in a vocational rehabilitation program

1. Lecomte T, Mireille C, Lesage AD, et al: Efficacy of a self-esteem module in the empowerment of individuals with schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187:406–413, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Brekke JS, Long JD: Community-based psychosocial rehabilitation and prospective change in functional, clinical, and subjective experience variables in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:667–680, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Lysaker PH, Clements CA, Wright DE, et al: Neurocognitive correlates of helplessness, hopelessness, and well being in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 189:457–462, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hoffman H, Kupper Z, Kunz B: Hopelessness and its impact on rehabilitation outcome in schizophrenia: an exploratory study. Schizophrenia Research 43:147–158, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Alloy LB, Abramson LY: Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: sadder but wiser? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 108:441–485, 1979Google Scholar

6. Beck AT, Weissman A, Lester D, et al: The measurement of pessimism: the Hopelessness Scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 42:861–865, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, et al: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual. Odessa, Fla, Psychological Assessment Resources, 1993Google Scholar

8. Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R. New York, Biometrics Research, 1994Google Scholar

9. Bryson G, Bell MD, Lysaker P, et al: The Work Behavior Inventory: a scale for the assessment of work behavior for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 20:48–54, 1997Google Scholar

10. Lysaker P, Bell M, Milstein, et al: Work capacity in schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:278–281, 1993Medline, Google Scholar