Day Hospital Treatment for Mood Disorders

Abstract

An increasing proportion of psychiatric patients are treated in day hospital settings, which are an effective alternative to hospital admission. The aim of this study was to determine the effectiveness of an intensive day program for patients with mood disorders. A series of 185 patients (102 women and 83 men with an average age of 55 years) who were consecutively referred to the psychiatric day hospital at A. Gemelli Hospital in Rome, Italy, and who met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for mood disorders were evaluated at admission, at discharge, and after six months. The study participants reported a significant reduction in symptoms as well as improvements in social adaptation and overall functioning.

During the past several decades various types of partial hospitalization programs have been developed with the purpose of offering either an effective alternative to hospital admission or an intermediate step after an inpatient stay. Studies have shown that a combination of inpatient treatment and a transitional day hospital program is an appropriate therapeutic approach for psychiatric patients (1). Other researchers have demonstrated that intensive milieu treatment can be effectively offered only on a day treatment basis (2,3). The aim of the study reported here was to assess the effectiveness of an intensive day program for patients with mood disorders and to investigate the relationship between the initial assessment results and the outcome results.

The day hospital protocol we examined is an intensive biopsychosocial program for patients with mood disorders. A specifically trained team of health care professionals comprising psychiatrists, residents, professional nurses, and social workers is involved in this program. Patients who are admitted to the day hospital agree to attend the hospital for four to six hours a day, five days a week, for a maximum of three weeks.

At admission all patients complete the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID- IV), and their depression and anxiety symptoms are measured with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS), the Zung Self-Rating Scale for Anxiety (Z-SAS), and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) as a means of assessing any differences between observer- and self-reported symptoms. In addition, the Social Adaptation Self-Evaluation Scale (SASS) is administered at admission.

The acute intervention strategies applied are focused on reducing the impact of symptoms, providing emotional support, encouraging social connection, and restoring working capacity. All patients' mental disorders and more intrusive symptoms—for example, anguish, anxiety, pain, insomnia, anger, compulsivity, and impulsiveness—are pharmacologically treated. In addition, the treatment plan is extended to the patient's family members, who receive psychological support during the patient's acute day hospitalization and participate in self-help groups for families and patients.

Methods

The study was conducted between March 2002 and May 2003. A series of 417 patients who were consecutively referred to the psychiatric day hospital at A. Gemelli Hospital in Rome, Italy, were interviewed with use of the SCID-IV. The study sample consisted of 185 patients (44 percent), who met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for mood disorders (4). All patients selected for the study completed mental-state assessment and underwent the day hospital program within two weeks. Informed consent and institutional review board approval were obtained.

Of the 185 patients, 102 (55 percent) were women and 83 (45 percent) were men. The patients' mean±SD age was 54.8±13.7 years. A total of 124 (67 percent) were married or cohabiting, 33 (18 percent) had never married, 20 (11 percent) were separated or divorced, and 18 (10 percent) were widowed. A total of 109 (58 percent) were employed. Sixty-nine patients (37 percent) had a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, 15 (8 percent) had recurrent major depressive disorder, 61 (33 percent) had bipolar disorder, eight (4 percent) had bipolar disorder type I, and 32 (17 percent) had bipolar disorder type II. Four patients (2 percent) had comorbid cluster A personality disorders, seven (4 percent) had comorbid cluster B disorders, and 11 (6 percent) had comorbid cluster C disorders.

The 185 patients were reassessed—with the HDRS, the HARS, the Z-SAS, the BDI, and the SASS—at discharge from the day treatment program and every week during the first two months and then every month for the next six months.

Results

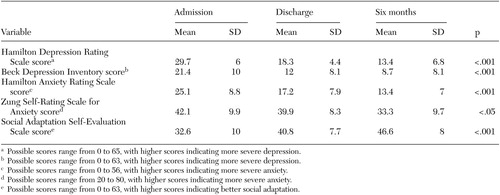

At discharge a significant improvement was observed among most of the treated patients. Mean scores on the depression scales decreased significantly (Table 1). The mean HDRS score improved from 29.7 at admission to 18.3 at discharge, and the mean BDI score improved from 21.4 to 12 (p<.001).

More rapid improvement in depressive symptoms was observed among depressed patients with comorbid dysthymic disorder, whereas those with comorbid personality disorder showed more moderate improvement. We observed a more rapid improvement in symptoms of depression among participants who were employed. Participants who cohabited with another person and those who lived alone showed more moderate improvement.

Most of the study participants are still in contact with us as outpatients. The changes observed after participation in day hospital treatment were either maintained or further improved at follow-up.

Discussion

There is no doubt that day hospital treatment is less costly than inpatient care. In the current environment of health care reform and rationing of services, greater emphasis is being placed on partial hospitalization programs (5). Nevertheless, literature reviews have indicated that these programs are still underused (6). Day hospital treatment has a dynamic structure: it can provide diagnostic and treatment services for acutely ill patients, it can offer treatment for patients experiencing some degree of remission from acute illness, and it can provide maintenance and rehabilitation for patients with chronic psychiatric illness (7).

Many studies have compared the relative efficacy of day treatment and inpatient care. A major limitation of these studies has been that, because of exclusionary criteria, many patients were not randomly assigned to inpatient or day hospital treatments (8). In many retrospective studies, day hospitalization appeared superior to inpatient treatment in measures of social and functional outcome and in prevention of readmission (9). On the other hand, the high rate of unplanned discharge from partial hospitalization programs suggests that this phenomenon could be a significant contributor to the underuse of this treatment modality (10).

Although several studies have supported the efficacy of day hospitalization for persons with acute disorders, few have determined which patients do well in day hospital settings. A lack of clarity in the definition of the appropriate clinical population, the purpose of the hospitalization, the length of stay, and the program elements as well as lack of standardization have contributed to the underuse of such programs.

In this study we explored the feasibility of introducing to a general hospital setting a day treatment program for a specific diagnostic subgroup of patients. We selected patients with acute affective symptoms for two main reasons. First, depressed patients accounted for almost half (44 percent) of acute admissions to the hospital. Second, previous studies have shown that this subgroup of patients has the highest success rate in partial hospitalization programs.

At six-month follow-up, 38 percent of the patients in our study continued to maintain improvements in symptoms and functioning, and 19 percent were in remittance. Most patients achieved a high level of clinical improvement within a three-week period. During the brief treatment period, depressed patients were helped to develop their own resources and instruments for coping with their mental pain in their social and family environments: both the patient and his or her family received therapeutic assistance, which enhanced the therapeutic benefits. We noticed that the supportive activities offered during day treatment were of great benefit to patients who did not have a primary support group, although these patients evidenced slower changes.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our data confirm the hypothesis that patients with serious mood disorders can be managed effectively in a short-term day hospital setting, particularly if their disorder is accompanied by acute stress or crisis and if they are employed and have a good primary support group. Day hospital treatment, which was once so popular, seems to be less visible in the literature today. Our study has contributed to the literature by demonstrating that short-term day programs are effective, and our findings support continuation and expansion of these programs with specific treatment targets.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry of Catholic University of Sacred Heart, Via Ugo De Carolis 48, 00136 Rome, Italy (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Symptom measures among 185 patients with mood disorders who participated in an evaluation of a day hospital program

1. Howes JI, Haworth H, Reynolds P, et al: Outcome evaluation of a short-term mental health day treatment program. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:502–508, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, et al: A randomized controlled trial of outpatient commitment in North Carolina. Psychiatric Services 52:325–329, 2001Link, Google Scholar

3. Sautter FJ, Heaney C, Hill, R, et al: The integration of inpatient treatment and a transitional day hospital: application of a problem-solving approach. Psychiatric Hospital 23:87–93, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

4. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

5. Bateman A, Fonagy P: Health service utilization costs for borderline personality disorder patients treated with psychoanalytically oriented partial hospitalization versus general psychiatric care. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:169–171, 2003Link, Google Scholar

6. Herz MI, Endicott J, Spitzer RL, et al: Day versus inpatient hospitalization: a controlled study. American Journal of Psychiatry 127:107–118, 1971Link, Google Scholar

7. Rosie JS, Azim HF, Piper WE, et al: Effective psychiatric day treatment: historical lessons. Psychiatric Services 47:876–877, 1995Google Scholar

8. Dick Ph, Sweeney ML, Cromie IK: Controlled comparison of day patient and outpatient treatment for persistent anxiety and depression. British Journal of Psychiatry 158:24–27, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Creed F, Black D, Anthony P, et al: Randomized controlled trial of day patient versus inpatient psychiatric treatment. British Medical Journal 300:1033–1037, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Gillis K, Russell VR, Busby K: Factors associated with unplanned discharge from psychiatric day treatment programs: a multicenter study. General Hospital Psychiatry 19:355–361, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar