Voting Preferences of Outpatients With Chronic Mental Illness in Germany

Abstract

Outpatients with chronic mental illness living in therapeutic residential facilities in Mannheim, Germany (N=110) responded to an opinion poll to determine their voting preferences for the 2002 federal election to the Bundestag. The poll found that the outpatients were significantly more likely than the general population in Mannheim to prefer left-wing parties (78 percent compared with 56 percent). This finding is in contrast to earlier reports; however, it seems to better reflect common beliefs about the political preferences of this population. In conclusion, persons with chronic mental illness seem to prefer political parties that they believe will best serve their perceived specific interests.

There are only a small number of studies of the voting behavior of psychiatric patients (1,2,3). Most of these studies were conducted to enhance patients' voting rights by demonstrating that persons with mental illness do not differ from the general population in their party preferences. None of these studies have found any significant differences between persons with mental illness and the general population; however, some studies have found that persons with mental illness tend to prefer political parties that are concerned with improving social conditions (for example, in the United States, the Democratic Party, in Europe, left-wing parties—the Social Democrats, the Green Party, and the Democratic Socialists). In addition, a statistically nonsignificant bias in favor of left-wing parties was found in a U.S. study of outpatients with chronic mental illness (4). It is commonly believed that this socioeconomically disadvantaged study population would have such a preference. Studies have also demonstrated that dissatisfaction with health leads to voting for left-wing parties (5).

Patients with chronic mental illness are the main target for empowerment, which has become a major concern of psychiatric patients during the past decade (6). Besides increasing patients' self-esteem and responsibilities, empowerment also focuses on enhancing patients' rights, mainly in terms of medical treatment but also in the area of civil rights. We investigated the hypothesis that an increase in empowerment raises political awareness among outpatients with mental illness and that an increase in political awareness increases empowerment. Increased patient empowerment should lead to voting behavior that is more oriented toward patients' interests, which would probably favor left-wing parties. Thus the main object of our study was to explore the current voting behavior of psychiatric patients in light of earlier findings of a nonsignificant trend toward left-wing preference.

Methods

Within one week after the federal elections to the German Bundestag in September 2002, all outpatients living in therapeutic residential facilities for persons with mental illness in Mannheim, Germany, were asked to indicate their voting preference, regardless of whether they were eligible to vote or whether they participated in the election. A short questionnaire was used to record party preferences and actual turnout at the election. Participation in the study was strictly voluntary; therefore, institutional review board approval was not required. Data on the voting behavior of the general population were obtained from the Federal Statistical Office of Germany. To control for possible regional differences in party preferences across Germany, only data for the general population in Mannheim were examined. Data processing and statistical analysis were done with SPSS 12.0.1 for personal computers.

Results

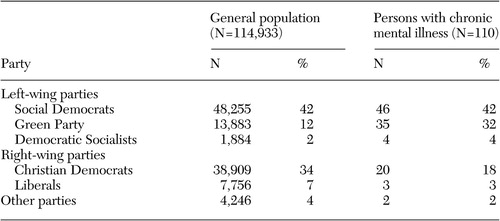

Of the approximately 215 outpatients with mental illness living in therapeutic residential facilities in Mannheim, 130 participated in our study. Twenty persons did not indicate their party choice and were excluded from further analysis. The resulting total of 110 respondents is 51 percent of the population of outpatients living in therapeutic residential facilities in Mannheim. Of these 110 patients, 54 percent voted in the elections, compared with 72 percent of persons in the general population in Mannheim. Table 1 shows preferences for party choice, regardless of whether patients actually voted.

Overall, 21 percent of the study population demonstrated that they preferred conservative parties (the Christian Democrats and the Liberals), whereas 41 percent of the general population in Mannheim voted for these parties (χ2=20.75, df=1, p<.001). Parties from the left wing (the Social Democrats, the Green Party, and the Democratic Socialists) were selected by 78 percent of the patients, but only 56 percent of the general population in Mannheim voted for these parties (χ2=20.75, df=1, p<.001).

Discussion

Our study had a number of limitations, especially concerning the question of whether the study population is a representative sample of outpatients with chronic mental illness. Given that only 51 percent of all outpatients with chronic mental illness living in therapeutic residential facilities in Mannheim answered the questionnaire, one might hypothesize that only patients who were more interested in politics and elections responded. On the other hand, this response rate could be considered fairly high considering that the overall study population has severe functional psychosis with a mean duration of illness of more than 15 years.

Regardless of representativeness, our findings on overall party preferences in 2002 seem to be fairly stable, because polls in the same facilities in 1994 and 1998 showed similar results, which were also statistically significant (7). However, the survey results of the 2002 elections were somewhat different than those of the 1994 and 1998 elections; in 2002 a shift was seen in which patients tended to vote for the Green Party instead of for the Social Democrats. This trend could be explained by the fact that the government in Germany has been formed mainly by the Social Democrats since 1998, in contrast to the 16 years of domination of conservative parties before this period. Special interests of psychiatric patients may not have been addressed during the time that the Social Democrats held power in Germany, resulting in a withdrawal of voters from this party in the 2002 election.

Although our data are probably not representative of all persons with chronic mental illness, we found that our study population showed a strong preference for left-wing parties. These findings are intuitively reasonable, because the study population is socioeconomically disadvantaged in some way, which can lead to a preference for parties that traditionally claim to represent the interests of this population. Previous studies have not demonstrated that persons with mental illness are significantly more likely than the general population to prefer left-wing parties. In fact, a study of outpatients from a community mental health center in the United States (4)—which surveyed a population comparable to ours in terms of diagnosis and duration of illness—showed only a nonsignificant trend toward left-wing preference. However, in the United States study (4), both the study population and the general population from the same geographic region tended to prefer more socially active parties. This finding may be explained by the fact that voters in the United States generally demonstrate much more stable voting behavior with pronounced regional preferences than do voters in Western Europe. Therefore, because all the studies in the United States (1,2,4) were conducted in regions with a well-established voting preference for the Democratic Party, the differences between psychiatric patients and the general population may have been masked by a strong traditional voting behavior of the respective control population.

Conclusions

The outpatients with chronic mental illness living in therapeutic residential facilities in Germany showed a significant preference for left-wing parties. We conclude that psychiatric patients are well aware of being socioeconomically disadvantaged and are voting for the parties that they believe to represent their interests best. Because the results of our study are different from earlier reports, it is also possible that recent activities to enhance empowerment among psychiatric patients led to these results.

There is no reason to exclude psychiatric patients from federal elections, which is still the case in a number of countries and U.S. states (8). There is also no reason to believe that patients' voting decisions are substantially influenced by their illness; the reasoning behind their voting decisions is similar to that of the general population, although patients do tend to prefer political parties that support the specific interests that result from being a psychiatric client (7). Participating in federal elections is an important opportunity for taking part in community activities as a whole (9). We encourage patients and patients' groups to use elections as another means for empowerment. Efforts to train persons with psychiatric disabilities for internships on boards and action groups can also be helpful (10). Further studies are necessary to determine whether specific interventions to enhance the participation of psychiatric patients in federal elections will result in increased empowerment and whether the converse is also true.

The authors are affiliated with the department of community psychiatry at the Central Institute of Mental Health, J5, Mannheim, GermanyD-68159 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Voting preferences for the 2002 federal election to the German Bundestag in the general population of Mannheim, Germany, and among outpatients with chronic mental illness who live in therapeutic residential facilities in Mannheim

1. Klein MM, Grossman SA: Voting competence and mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 127:1562–1565, 1971Link, Google Scholar

2. Howard G, Anthony R: The right to vote and voting patterns of hospitalized psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Quarterly 49:124–132, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Jaychuk G, Manchanda R: Psychiatric patients and the federal election. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 36:124–125, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Duckworth K, Kingsbury SJ, Kass N, et al: Voting behavior and attitudes of chronic mentally ill outpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:608–609, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Kelleher C, Timoney A, Friel S, et al: Indicators of deprivation, voting patterns, and health status at area level in the Republic of Ireland. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 56:36–44, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Geller JL: The last half-century of psychiatric services as reflected in psychiatric services. Psychiatric Services 51:41–67, 2000Link, Google Scholar

7. Bullenkamp J, Voges B: Wahlverhalten chronisch psychisch kranker [Voting behavior of the chronic mentally ill]. Psychiatrische Praxis 30:444–449, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Hemmens C, Miller M, Burton VS Jr, et al: The consequences of official labels: an examination of the rights lost by the mentally ill and mentally incompetent ten years later. Community Mental Health Journal 38:129–140, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Nash M: Voting as a means of social inclusion for people with a mental illness. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 9:697–703, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rowe M, Benedict P, Falzer P: Representation of the governed: leadership building for people with behavioral health disorders who are homeless or were formerly homeless. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 26:240–248, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar