Psychotic-Spectrum Symptoms, Trauma, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Suicidal Inner-City Women

Abstract

This study explored psychotic-spectrum symptoms, trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and suicidal intent among low-income inner-city women who were admitted to a community hospital after a suicide attempt. Measures included the Brief Symptom Inventory, the Traumatic Stress Schedule, the National Women's Study PTSD module, and the Suicide Intent Scale. Psychotic-spectrum symptoms, trauma, and PTSD were significantly correlated. Trauma and psychotic- spectrum symptoms, but not PTSD, were associated with suicidal intent, although the effect sizes were small. Psychotic symptoms mediated the relationship between PTSD and suicidal intent. These results emphasize the need for attention to all of these variables in assessing clinical complications and comorbid conditions.

A growing body of literature explores the interface between psychotic-spectrum symptoms, psychological trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These factors can produce complex clinical presentations that are often misdiagnosed and undertreated, leading to greater severity of symptoms and significant clinical complications, such as suicidality.

Most research has explored psychosis and related diagnoses either as a primary disorder complicated by trauma and PTSD (1) or as a complication and potential subtype of PTSD (2). In either case, disease burden has been demonstrated to increase significantly, with diminished adaptive coping, greater chronicity of illness, poorer response to treatment, poorer long-term outcomes, and higher levels of suicidality (1,2,3,4).

In this retrospective study we examined associations among psychotic-spectrum symptoms, traumatic events, PTSD, and suicidal intent. We hypothesized that significant relationships would be found among all these variables. Specifically, consistent with literature postulating psychoticism as a severe subtype of PTSD (2), the analysis aimed to examine the effects of trauma and PTSD on psychotic symptoms.

Methods

Procedures

The study data, collected from November 1995 through March 1997, were drawn from a larger study of suicidality and interpersonal violence (5). The study participants, recruited from a level 1 public hospital serving an urban, low-income population, had presented for emergency treatment after a suicide attempt. Exclusion criteria were presence of a life-threatening medical condition, significant cognitive impairment as assessed by the Mini-Mental State Exam (6), or acute psychosis or delirium so severe as to preclude meaningful informed consent or study participation. Four potential participants were excluded, and 11 refused to participate.

When the participants were medically stable, they signed informed consent forms, approved by the institutional review boards of Emory University and Grady Health System, and completed oral administration of self-report questionnaires. The participants were compensated $25 and provided with a community resource list.

Measures

Brief Symptom Inventory. The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (7), a 53-item self-report instrument, assesses overall psychological distress and specific symptom domains. This study used two five-item subscales that together capture elements of psychotic continuum dysfunction. The psychoticism subscale measures symptoms ranging from schizoid withdrawal to positive symptoms of schizophrenia. The paranoid ideation subscale assesses paranoid behavior as it manifests in thought disorder. The subscale scores are item means. Possible scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores reflecting a greater number of symptoms.

Traumatic Stress Schedule. The Traumatic Stress Schedule (TSS) (8), a structured interview, asks about the occurrence of 16 traumatic life events during three stages of life: childhood (before the age of 18 years), adulthood (after the age of 18) excluding the past year, and adulthood within the past year. From the TSS, an index of lifetime trauma frequency was calculated by summing the number of positive responses for the 16 types of trauma over the three life stages, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 48.

National Women's Study PTSD module. The National Women's Study PTSD module (NWSPTSD) (9), a structured clinical interview based on DSM-III-R criteria for PTSD, assesses current and lifetime PTSD symptoms. Possible scores range from 0 to 17, with higher scores indicating more symptoms.

Suicide Intent Scale. The Suicide Intent Scale (SIS) (10), a clinician-rated scale, measures the seriousness of the desire to die in a suicide attempt. The first 15 items (of a total of 20) are summed for a total intent score ranging from 0 to 30.

Results

The study participants were 200 women with a mean±SD age of 30.82±9.2 years (range, 18 to 62 years). The ethnic breakdown was 176 (88 percent) African American, 16 (8 percent) Caucasian, five (2.5 percent) Latina, two (1 percent) Asian, and one (.5 percent) of unknown ethnicity. A majority (119 participants, or 60 percent) had completed at least 12 years of education, and 56 (28 percent) were employed.

The sample means for key variables were BSI psychoticism subscale, 1.7±1.04; BSI paranoid ideation subscale, 2.07±1.08; TSS trauma frequency index, 6.85±3.15; NWSPTSD current PTSD score, 7.21±4.86; and SIS score, 10.48±5.89.

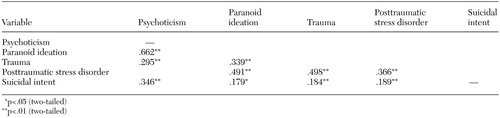

In initial data analysis, bivariate correlations among key variables were significant, as can be seen in Table 1. The combined effects of trauma frequency and PTSD on the psychotic-spectrum variables were then examined in two hierarchical multiple regression analyses with psychoticism and paranoid ideation as dependent variables in respective equations. The independent variables were trauma and PTSD, entered in that order. In both equations, the model was significant (psychoticism, F=34, df=2, 197, p<.001, R2=.26; paranoid ideation, F=37.56, df=2, 197, p<.001, R2=.28). In both equations, although significant main effects were found for both trauma and PTSD, the effect sizes for PTSD (R2=.17 for psychoticism and .15 for paranoid ideation) as well as the final betas (psychoticism, .44 for PTSD and .13 for trauma; paranoid ideation, .43 for PTSD and .18 for trauma) suggest the relative importance of the association between PTSD and psychotic-spectrum symptoms.

To examine these variables relative to suicidal intent, a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was conducted, with suicidal intent as the dependent variable and with independent variables in the following order: trauma frequency, PTSD, and—combined in a single step—psychotic-spectrum symptom variables (psychoticism and paranoid ideation). The model was statistically significant (F=7.58, df=4, 195, p<.001, R2=.14), with main effects for trauma (F change=6.93, df=1, 198, p<.01, R2 change=.03) and for combined psychotic-spectrum symptoms (psychoticism and paranoid ideation) (F change=9.42, df=2, 195, p<.001, R2 change=.08), although the effect sizes were small for both. PTSD was not significantly associated with suicidal intent. Given previous results showing significant association between PTSD and psychotic-spectrum symptoms, post hoc mediation analyses were conducted, revealing that both psychotic-spectrum symptoms (psychoticism and paranoid ideation) mediated the relationship between PTSD and suicidal intent.

Discussion and conclusions

This study demonstrated significant relationships among trauma, PTSD, psychotic-spectrum symptoms, and suicidal intent in a sample of low-income inner-city women. PTSD was more heavily weighted than trauma in its association with psychotic-spectrum symptoms. Because this study was correlational, causality could not be discerned. Psychotic-spectrum symptoms may predispose a person to traumatic events and the development of PTSD. However, trauma and PTSD may precipitate the expression of psychotic-spectrum symptoms.

The findings of this study suggest that trauma, PTSD, and psychotic-spectrum symptoms may be risk factors for suicidality, with PTSD influencing suicidal intent through its relationship to psychotic symptoms. However, although these results were statistically significant, the practical clinical significance is less clear given the small effect sizes. Caution may be needed in interpretation of these data. Nonetheless, given the convergence of this finding with those of other studies and the gravity of suicide as a potential complication of PTSD and trauma, a conservative stance would be to call clinical attention to the potential for suicidality in the assessment and treatment of trauma and PTSD accompanied by psychotic symptoms.

The limitations of this study include lack of diagnostic data; restricted income range, which limits generalizability; exclusion of persons whose psychosis was so acute that meaningful informed consent and participation were precluded, which created an artificial ceiling for a key variable; and use of retrospective, cross-sectional, self-reported data, which opened the possibility of response bias and limited exploration of causality. Future research should address these limitations, use prospective designs, and examine more fully the complex relationships among these variables and other key variables—for example, depression—in predicting suicidality.

This study contributes to a growing body of literature addressing the links between psychotic-spectrum symptoms, trauma, PTSD, and suicidality. Clinically, these results alert clinicians to potential comorbid conditions and the need for careful assessment and differential diagnosis to inform appropriate and targeted treatment protocols.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant 5-29240 from the Association of Schools of Public Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry to Dr. Kaslow.

Dr. Reviere, Dr. Farber, and Dr. Kaslow are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. Dr. Battle is with the department of psychology at Brenau University in Gainesville, Georgia. Send correspondence to Dr. Reviere at 1151 Sheridan Road, Atlanta, Georgia 30324 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Matrix showing significant correlations of major variables in a clinical sample of suicidal low-income inner-city women

1. Mueser KT, Goodman L, Trumbetta SL, et al: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:493–499, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hamner MB, Frueh BC, Ulmer HG, et al: Psychotic features in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder and schizophrenia: comparative severity. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 188:217–221, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Farber E, Herbert S, Reviere S: Childhood abuse and suicidality in obstetrics patients in a hospital-based urban prenatal clinic. General Hospital Psychiatry 18:56–60, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Radomsky ED, Haas GL, Mann JJ, et al: Suicidal behavior in patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1590–1595, 1999Link, Google Scholar

5. Kaslow NJ, Thompson MP, Meadows LA, et al: Factors that mediate and moderate the link between partner abuse and suicidal behavior in African American women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:533–540, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: Mini-Mental State: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 12:189–198, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Derogatis LR: The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring, and Procedures. Manual II, 2nd ed, Baltimore, Clinical Psychometric Research, 1992Google Scholar

8. Norris F: Screening for traumatic stress: a scale for use in the general population. Journal of Psychiatric Research 20:1704–1718, 1990Google Scholar

9. Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, et al: Rape, other violence against women, and post traumatic stress disorder, in Adversity, Stress, and Psychopathology. Edited by Dohrenwend BP. New York, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

10. Beck AT, Schuyler D, Herman I: The development of suicide intent scales, in Prediction of Suicide. Edited by Beck AT, Resnick HL, Littiere DJ. Bowie, Md, Charles Press, 1974Google Scholar