Feasibility of a Skills Training Approach to Reduce Substance Dependence Among Individuals With Schizophrenia

Abstract

A novel treatment for persons who have both schizophrenia and substance abuse was evaluated by incorporating cognitive-behavioral drug relapse prevention strategies into a skills training method originally developed to teach social and independent living skills to patients with schizophrenia. Thirty-four of 56 patients completed treatment and a three-month follow-up assessment. Participants learned substance abuse management skills and reported that they found the treatment relevant, useful, and satisfying, and their drug use decreased. Improvements were noted in medication adherence, psychiatric symptoms, and quality of life. This manual-driven therapy may play an important role in the treatment of substance abuse among patients with schizophrenia.

Substance abuse is common among persons with serious mental disorders. Standard substance abuse treatments are often fragmented and ineffective (1). Although integrated treatments may hold promise, it is less clear which substance abuse treatments to employ. Most treatments attempt to teach new concepts and skills, yet severe mental disorders often interfere with learning (2).

Behavioral skills training can overcome learning deficits among persons with mental illness. Skills training has improved psychosocial outcomes among patients with schizophrenia (3) and has been used to treat substance abuse among persons who do not have mental disorders. These approaches, based on a foundation of relapse prevention (4), identify high-risk situations and alternative coping strategies and use modeling, role playing, and feedback to improve coping skills.

Efforts are under way to adapt substance abuse treatments for persons with dual diagnoses. Bellack and colleagues (5) have developed a comprehensive program. However, this program may be difficult to replicate.

A component approach might make it easier to implement behavioral treatment, one component at a time, in a range of settings. Consequently, we focused on behavioral rehearsal of a small set of skills that might be crucial for drug avoidance—for example, refusing drugs. Here we report results of a feasibility study focused narrowly on behavioral rehearsal of a small set of skills that might be crucial for drug avoidance. The treatment includes some psychoeducation and relapse prevention concepts, but only to the minimum extent necessary to set the stage for behavioral rehearsal.

Methods

The substance abuse management module (SAMM) (6) is based on the relapse prevention and harm reduction concepts of Marlatt and Gordon (4) for persons with substance abuse who do not have mental illness. The training methods are based on the social and independent living skills modules of Liberman and colleagues (7).

SAMM was developed and tested in the dual diagnosis treatment program at the West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center. This program consists of an interdisciplinary team that provides pharmacologic interventions, intensive case management, psychoeducational groups, skills training, and regular urine toxicology analysis. A bachelor's-level therapist with no previous experience treating patients with a dual diagnosis provided SAMM training. Monthly fidelity checks using scales keyed to specific therapist behaviors indicated that the therapist strictly adhered to the SAMM protocol.

Study participants were recruited as they entered the dual diagnosis program's day hospital. We excluded patients whose psychiatric symptoms were determined to be solely drug induced. The medical center's institutional review board approved the study, and all participants gave informed consent. Participants were paid a small sum for completing three research assessments but not for participation in the treatment sessions or for travel. The study was conducted in 1996 and 1997.

These patients were severely mentally ill and chronically substance dependent. They had long histories of substance use and extensive recent use of cocaine, marijuana, or other substances. None were employed, and many (17 patients, or 30 percent) were homeless. Diagnoses were determined on the basis of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.

Measures of substance abuse management and skills taught in the module, satisfaction with treatment, drug and alcohol use, psychopathology, medication adherence, social functioning, and quality of life were administered before and after treatment and at a three-month follow up.

Drug use was measured by using the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (8) and twice-weekly urine tests. Missed tests were counted as positive for drug use. Psychiatric symptoms were measured with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (9), and medication compliance was assessed as the number of days on which the patient took antipsychotic medication in the previous 30. Quality of life was measured with the global rating subscale of a quality-of-life interview (10).

Acquisition of drug relapse prevention skills was measured by using the SAMM content mastery test for patients (SCMTP), a role-playing test of knowledge and skills designed for this study. The test revealed excellent item-total correlations and an alpha coefficient of .86. Patient satisfaction was measured at completion of skills training by using the SAMM Consumer Satisfaction Survey (SCSS), which assessed the degree, measured on 5-point Likert scales, to which patients anonymously expressed satisfaction with all components of the module, the performance of the group leader, and a comparison of SAMM training with other treatment programs previously attended.

The general linear mixed model was used in maximum-likelihood repeated-measures analyses of covariance (ANCOVA), permitting analysis of repeated measures with missing data and time-varying covariates and detailed analysis of trends, including linear and nonlinear components during the three phases of the study. Analysis of trends was conducted by computing linear slopes over time and using these as dependent variables in least-squares ANCOVA and multiple regression. Simple t tests for correlated means assessed changes from pretreatment to posttreatment and from posttreatment to follow-up. Categorical variables were assessed with the McNemar chi square statistic.

Results

Thirty-four of the 56 participants (61 percent) completed the study. In nearly all cases, patients who dropped out were those who had been recruited on the day of their first outpatient visit to the dual diagnosis program but who never returned for subsequent appointments. Aside from a slight difference in homelessness status, those who completed the study and those who did not complete it did not differ on any of over 30 demographic variables or on any of the pretreatment assessments of outcome variables.

SAMM sessions were offered five times weekly. The mean±SD time to complete the module was 15±5.1 weeks, during which participants attended a mean of 54±7.2 sessions. SCMT scores indicated that participants readily learned the skills taught. Satisfaction ratings were uniformly high on all items and subscales (above 4 on a scale ranging from 1, low satisfaction, to 5, high satisfaction). None of the participants made negative comments about the module.

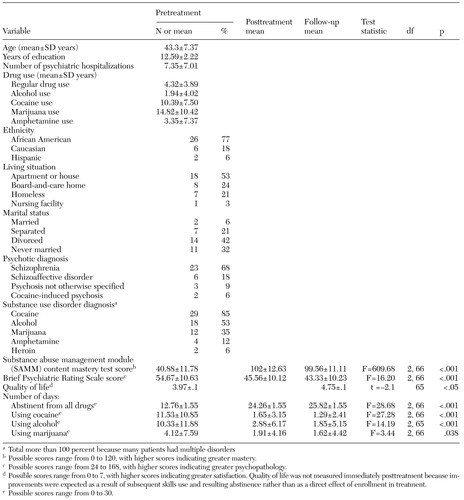

The number of days on which patients used drugs of abuse declined significantly over the study period, and the number of days of complete abstinence in the previous month showed a marked increase, as can be seen in Table 1. Medication adherence improved significantly and remained high at three months (McNemar χ2=13.23, df=1, p=.001). All patients were taking newer atypical antipsychotics. None were maintained on depot medications. Symptoms and quality of life improved significantly after treatment and remained improved at follow-up.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, chronically psychotic substance abusers attended treatment regularly and were able to learn and maintain a range of drug relapse prevention concepts and skills. They found SAMM to be highly relevant, useful, and satisfying, suggesting that it may be feasible to integrate the module into existing mental health programs. The study's retention rate—61 percent—was typical for persons with substance dependence and severe mental illness who are in comprehensive treatment programs.

The goal of this study was to test feasibility, not efficacy. However, large and significant improvements were noted in drug and alcohol abstinence, psychiatric symptoms, medication adherence, and quality of life. Moreover, these improvements were correlated with participation in SAMM. However, these changes could have resulted from at least three factors other than the use of the skills taught. All the participants entered the study immediately after acute hospitalization. The improvements might represent the natural course of recovery after a crisis. The participants were enrolled in a comprehensive dual diagnosis treatment program, and other components of this program may have been responsible for the improvements. Finally, even if SAMM was responsible, these improvements might be due to some feature of SAMM other than participants' use of the skills they learned. Consequently, any attempt to generalize these findings must be made cautiously. Future research should test the feasibility of SAMM in other clinical settings, use a randomized control group, and determine whether participants used the skills taught.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by grant R01-DA09436-NH49 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Dr. Shaner and Dr. Eckman are with the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. They are also with the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Medicine, with which Mr. Fuller is affiliated. Dr. Roberts is with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle and with the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center of the Department of Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Healthcare System in Seattle. Send correspondence to Dr. Shaner at Department of Psychiatry (116A), West Los Angeles VA Medical Center, 11301 Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90073 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics and outcomes at posttreatment and three-month follow-up among 34 patients with a dual diagnosis who completed a study to test a skills training module

1. Drake RE, Mueser KT: Managing comorbid schizophrenia and substance abuse. Current Psychiatry Reports 3:418–422, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Gold JM, Harvey PD: Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 16:295–312, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Dilk MN, Bond GR: Meta-analytic evaluation of skills training research for individuals with severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:1337–1346, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Marlatt GA, Gordon JR: Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York, Guilford, 1985Google Scholar

5. Bellack AS, Gearon JS: Substance abuse treatment for people with schizophrenia. Addictive Behaviors 23:749–766, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Roberts LJ, Shaner A, Eckman TA: Overcoming Addictions: Skills Training for People With Schizophrenia. New York, W. W. Norton, 1999Google Scholar

7. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Robertson MJ: Dissemination of skills training. Psychiatric Services 53:215, 2002Link, Google Scholar

8. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, et al.: New data from the Addiction Severity Index: Reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 173:412–423, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Ventura J, Lukoff D, Neuchterlein KH, et al: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) expanded version (4.0): scales, anchor points, and administration manual. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 3:227–243, 1993Google Scholar

10. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Programming 11:156–161, 1988Google Scholar