Medicaid, Health Care Financing Trends, and the Future of State-Based Public Mental Health Services

Abstract

Medicaid now funds more than half of public mental health services administered by states and could account for two-thirds of such spending by 2017. This trend and others represent a major shift in the predominant model by which public mental health services are funded, organized, and delivered. One model is associated with programs administered by state mental health authorities and is characterized by direct funding of designated community providers. This model is being displaced by one associated with state Medicaid programs, which are based on organization and financing methods characteristic of health insurance plans. This shift in models encompasses issues such as administrative authority, funding source, data collection, population served, services provided, and attitudes toward providers and consumers. Failure to understand these changes and their implications will probably have negative consequences.

The latest available national estimates show that $73 billion was spent on mental health services in the United States in 1997 (1). Of this amount, 55 percent, or $40.5 billion, came from public sources. Nearly three-quarters of this public spending was for programs and services administered by state and local governments (2).

Over the past ten to 15 years, changes in the ways in which this state and local component is financed are having important effects on the organization and delivery of public mental health services. The most visible aspect of these changes has been the widespread adoption of managed care programs by states to control growing expenditures. However, other financing and system trends are also having a major effect on the public mental health services system. This article identifies these trends and examines their current and potential effects on the administration and delivery of care.

The community model of state mental health services

To a considerable degree, issues of state mental health services continue to be conceptualized within a model of organization and financing that reasonably characterized the services system 15 or 20 years ago, referred to here as the community model. This model has several major features. One is that the planning and administration of public mental health services are centered in a state (sometimes county) mental health authority. It is generally assumed to be an autonomous agency in state government, with independence in setting policies and exercising oversight.

The community model also views state mental health authorities as being the primary funders of public mental health services. One way this funding is accomplished is through direct provision of services, chiefly in public psychiatric institutions. Equally important, however, are expenditures for the support of community-based specialty providers. These providers most often are nonprofit agencies that serve indigent populations or clients of publicly supported programs, particularly persons with serious disorders. Often these providers do not specialize in one type of treatment but offer services across the continuum of care.

State mental health authorities have most often used a system of grants or contracts to support this specialty provider network. Generally, this funding is available only to providers designated as principal providers of publicly funded mental health services in their communities. In exchange, these providers are expected to identify and address the mental health needs of persons in their community or catchment area who have limited income or no insurance and who have the most serious disorders. Within parameters set by the state mental health authority, the community model views these providers as having some discretion in designing programs, choosing clinical staff, and setting treatment guidelines.

The actions of officials concerned with state-based public mental health services are directed by the assumptions underlying the community model. Federal programs aimed at expanding or improving public mental health services most often target either state mental health authorities or "communities" as the chief agents for the design and funding of public mental health services. For example, the stated goal of the federal Community Action Grant Program is to "assist communities in building consensus around planning for the adoption of exemplary practices" (3).

Another example concerns efforts to improve the quality and accountability of the public mental health services system. For the past several years, state mental health authorities and the federal government have worked to develop a uniform set of performance measures for state mental health systems. These measures have generally targeted services directly provided or funded by the state mental health authority.

For example, directions for one measure, "penetration/utilization rates," specify that the numerator should be composed of the unduplicated number of people served by state hospitals plus those served by community mental health programs that are "operated or funded by the state mental health authority" (4). Further evidence of this orientation comes from a document providing operational definitions for this and other measures, which describes them as "State Mental Health Agency Performance Measures" (5).

Medicaid and financing trends

The community model still characterizes a significant part of the state-based public mental health services system. However, this proportion is shrinking and already probably characterizes less than half of the total system, chiefly because of the growing dominance of Medicaid.

Although Medicaid has always played a role in public mental health services, only recently have studies detailed the size of this role and how it is changing. Chiefly, an ongoing project of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration that estimates national spending for mental health services is providing information on funding trends that was missing from previous efforts (1). This work shows that more than 70 percent of public spending for mental health services occurs in programs administered at the state and local levels (2). This state and local component consists mostly of Medicaid and other programs funded directly by state or local governments. More recently, another joint federal-state program, the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP), was added to this component.

The growth of Medicaid

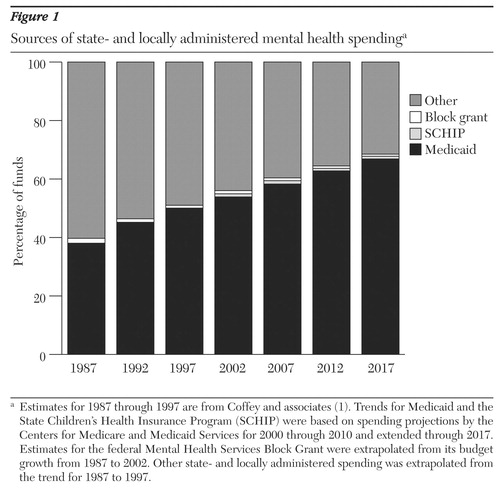

Figure 1 shows changes in the relative size of the sources of payment for state- and locally administered mental health services. Estimates for 1987 through 1997 are from the study by Coffey and associates (1). For the remaining years, figures for other state- and locally administered spending were extrapolated from the trend for 1987 to 1997.

Trends for Medicaid were based on spending projections for 2000 through 2010 provided by the office of the actuary in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and extended through 2017. Little information is available by which to estimate mental health services spending in SCHIP. Therefore, for these estimates, it was assumed that the ratio of mental health services spending in that program to Medicaid mental health services spending was the same as the ratio of the total spending in the two programs. Estimates for the federal Mental Health Services Block Grant, called "block grant" in the legend, were extrapolated from its budget growth from 1987 to 2002.

These trends show a dramatic change in the role of Medicaid as a payer for state and local mental health services. Medicaid accounted for slightly more than a third of such funding in 1987 but had already assumed equal importance with other state- and locally funded programs by 1997. If this trend continues, Medicaid should account for two-thirds of state and local mental health services spending by 2017. On the other hand, although much attention has been given to the recent creation of SCHIP, Figure 1 shows that it will be only a very minor source of funds for the foreseeable future, as will the federal Mental Health Services Block Grant program.

Factors affecting Medicaid growth

Several factors have contributed to Medicaid's growth and will probably continue to do so. One is Medicaid's general character as an entitlement and insurance program. Spending for this type of program is more difficult to restrain than spending for services delivered directly by public agencies or funded through grants or contracts. Expansion in federally mandated eligibility has also contributed to Medicaid spending growth.

Not all factors contributing to Medicaid spending growth are outside states' control. Mental health services is one area in which states have actively contributed to this growth. One way in which they have done so is through their efforts to decrease the size of the populations of public psychiatric institutions (6). Services for individuals between the ages of 22 and 64 years in psychiatric institutions are generally ineligible for Medicaid support (7). Reducing the size of these populations has meant that persons who previously may have been supported entirely at the state's expense might now have some or all of their services paid for by Medicaid. From 1986 to 1998, more than 50,000 beds were closed in state and county mental hospitals (8).

Another way in which states have increased Medicaid mental health services spending is through disproportionate share payments to psychiatric hospitals. These payments are meant to reimburse hospitals for the uncompensated costs of care provided to low-income and Medicaid patients. Changes made in the program in the late 1980s resulted in large increases in disproportionate share payments, which rose from $1.4 billion in 1990 to $15.4 billion in 1997 (9,10). A substantial proportion of these funds are for psychiatric institutions, mostly state hospitals. In 1997, disproportionate share payments of $3 billion went to these facilities (9).

A more important factor contributing to the growth of Medicaid mental health services spending has been the refinancing of state and county mental health services. Also referred to as "Medicaid maximization," this process converts services previously funded entirely by state or local funds into those eligible for Medicaid support. This conversion allows states to expand services at no additional cost to them and to increase federal Medicaid revenues. Although states have taken such actions for a variety of public services, mental health services during the 1990s were the most common area of maximization efforts (11).

Some of these factors will not be as important over the next decade as they were during the 1990s. Reductions in the populations of psychiatric institutions will be smaller and thus will not contribute as greatly to increases in Medicaid mental health services spending. Similarly, changes in the law affecting disproportionate share payments mean that psychiatric hospital payments will decrease somewhat.

Nevertheless, other trends will probably ensure that Medicaid's share of state-based public mental health services spending will continue to increase. First, Medicaid spending in general is projected to increase at an annual rate exceeding 8 percent over the next decade (12). Even in fiscal year 2003, when many states are implementing Medicaid cuts as a result of adverse fiscal conditions, state budget officers still project that Medicaid spending will grow by 5 percent (13). Spending focused on mental health services within the program will probably reflect these trends. Second, efforts to qualify state-funded mental health services for Medicaid, and thereby to increase federal revenue for the states, almost certainly will continue. Smith and associates (11) showed that such efforts were partly prompted by the kind of adverse fiscal conditions that states are now experiencing.

A secondary way in which the proportion of Medicaid spending on mental health services will increase is through Medicaid's indirect effects on the budgets of state mental health authorities. The receipt of federal matching funds means that states have strong incentives to limit growth in other programs before limiting Medicaid. As a result, when revenues are limited, states are more likely to look to non-Medicaid mental health services spending for savings.

Most state mental health authorities administer some part of the mental health services funded by Medicaid. Maximization efforts that bring services administered by state mental health authorities into Medicaid, along with the higher general growth rate of Medicaid, means that Medicaid accounts for a larger and larger proportion of the budgets of state mental health authorities. From 1987 to 2001, the percentage of the budgets of state mental health authorities that was funded by Medicaid nearly tripled, from 13 to 36 percent (14). During the 1990s, Medicaid accounted for 61 percent of the overall growth in state mental health authority budgets (15).

These changes have been reflected in the revenues of community-based specialty providers. A national survey of such providers conducted periodically by the National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare (formerly the National Council of Community Mental Health Centers) (16) showed that Medicaid accounted for only 8 percent of revenues in 1985. In that year, state government, local government, and the federal block grant program were all more important sources of funding. By 2002, however, Medicaid had become the largest single source of revenue for community providers, accounting for 38 percent of their total funding (17).

Other financing trends

In addition to the effects discussed above, three larger trends in health care policy and spending are embodied in Medicaid. The first of these is the growing emphasis on programs or strategies to increase the number of Americans who have some form of health insurance. The second trend is the adoption by the public sector of models of coverage and administration generally developed and applied within private health plans. The third trend is the increasing proportion of all publicly financed mental health care paid for by federal, rather than state or local, dollars.

Although the Clinton administration failed to fundamentally reorganize the system of national health care, its efforts nevertheless confirmed a general shift in the approach to problems of health services delivery. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, federal policies supported the creation and expansion of health care entitlement programs, chiefly Medicare and Medicaid. These policies also promoted grant-supported public health services, such as the Community Mental Health Centers program. Beginning in the 1980s, however, support for the expansion of grant programs began to decline. Emphasis is now almost entirely on the expansion of public and private insurance as the preferred policy approach for addressing access to health services. For instance, the chief health policy initiative of the past decade has been the passage of SCHIP. Moreover, during the last presidential campaign, both candidates generally agreed on the need to expand health insurance coverage, although they disagreed on the best method of doing so. Neither candidate proposed new public health grant programs or significant expansion of existing ones.

As publicly funded health services have increasingly focused on insurance-based models, methods of organization and financing that were developed in the employer-based insurance market have been adopted by the public system. By far the most visible aspect of this adoption has been the group of methods referred to as managed care. Within Medicaid, enrollment in some form of managed care increased from 9.5 percent of the covered population in 1991 to 57.6 percent in 2002 (18,19). In 2000, some type of managed behavioral health care program was being operated by 39 states (20).

More recently, an area in which private insurance methods have been adopted by the public sector is that of benefit packages. Increasingly, proposals to expand coverage of uninsured persons are using standards of coverage commonly seen in the private sector. The predominant example of this approach is SCHIP, which offers states the option of covering uninsured low-income children through one of several "benchmark" plans based on prevalent private plans in the states. For mental health, requirements are only that a state SCHIP program provide 75 percent of the actuarial value of the benchmark mental health benefit. In addition, some demonstration waiver options in both Medicaid and SCHIP have allowed states to expand coverage for uninsured persons by providing plans that have no mental health coverage of any kind or by supporting the purchase of health insurance offered through individual private employers, which sometimes has few or no mental health benefits.

Another feature of private-sector health care concerns attitudes about providers. Although managed care and other health plans have often designated networks of providers, these providers are not primarily selected for their longevity in the community or even their history with a particular health plan. Rather, network participation is more strongly determined by considerations such as ability to meet credentialing standards and willingness to accept the payment rates offered. This approach promotes competition among providers. It also does not assume that the plan has any significant responsibility for maintaining the participation or the financial health of any particular provider.

Finally, although this article focuses chiefly on state-administered sources of funding, Medicare also is a major source of public funding for mental health services. In 1997 it accounted for 22 percent of such funding (1). The increase in this payment source, with the increase in Medicaid, means that the federal contribution to total public mental health services spending is growing faster than the state and local contribution. From 1987 to 1997, the inflation-adjusted rate of growth for the federal share was 6.3 percent, compared with 2.4 percent for the state and local share (1). This larger rate of growth meant that federal dollars accounted for a little more than half of all spending for public mental health services in 1997, up from about 40 percent in 1987. If these growth rates continue, the federal share of public mental health services spending should exceed 60 percent by 2007.

The health plan model of state mental health services

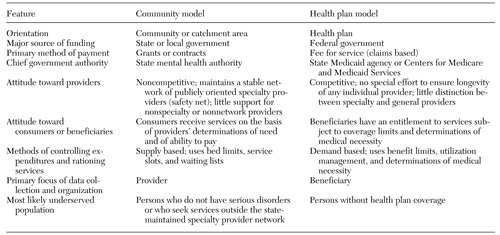

Because of the trends described earlier, a health plan model of organization and financing for public mental health services is gradually displacing the community model. Table 1 shows the major features of this model alongside those of the community model. One major feature of the health plan model is a method of services financing similar to those of private health plans but based primarily on Medicaid funding. Associated with this model is a greater reliance on federal spending to support the system as well as the dominance of Medicaid authorities, not state mental health authorities, in the determination of policies governing the administration and delivery of services. This domination also means that federal influence on state mental health services will increase through Medicaid and that the influence of local authorities and communities will decrease.

Because the health plan model is based on an insurance approach to services provision, it generally does not conceptualize service delivery in terms of a community or a catchment area. Rather, issues of utilization and quality are conceptualized in terms of a health plan and its covered population. This population is viewed as having an entitlement to services, subject to coverage limits and determinations of medical necessity. These forms of demand controls also are the chief means by which spending is managed and services are rationed. This contrasts with the supply-based methods that characterize the community model.

Funding for services under the health plan model most commonly takes the form of claims-based fee-for-service payment for covered services to enrolled beneficiaries. The change from the grant or contract form of reimbursement characteristic of the community model to the insurance-based reimbursement characteristic of the health plan model means that providers have considerably less discretion about the amount and nature of services and who may receive them. Instead, services are determined by the benefit coverage, network policies, and utilization management practices of the health plan, primarily Medicaid. Related to this change is a shift in the way in which publicly oriented specialty providers are viewed. Under the health plan model, few distinctions are made among providers delivering similar services, and less importance is attached to maintaining the continued operation of any provider.

Because of its emphasis on a specialty provider network, data collection in the community model focuses on documenting provider behavior related to program purposes. Thus data records often show a provider's contacts with a particular individual but are nonspecific about the type or quantity of services that may have been delivered as a result of that contact. In contrast, the fee-for-service payment method of the health plan model supports databases that maintain information at the individual level about specific types and quantities of services.

A final area of difference between the community model and the health plan model is related to which groups are most likely to be underserved in each model. In the community model, funding is targeted to groups with the most serious disorders who seek treatment from the state-supported specialty network. Therefore, those who have less serious disorders or who seek care outside the network are likely to meet the greatest barriers to service. This situation changes in the health plan model, in which the group most likely to be underserved is uninsured persons—those without private or public coverage.

Implications of the health plan model

A number of changes are likely to occur as administrators, policy makers, and interest groups increasingly understand the implications of the health plan model of state-based public mental health services. The areas likely to be affected by these changes are the organization of state government agencies, data systems and performance measurement, state mental health planning and reporting, characteristics and roles of specialty providers, federal grant programs, and the advocacy focus of mental health interest groups. Very few of these changes are completely new. In almost all of these areas, some evidence exists of the directions outlined below. However, examples of them will probably become broader and more frequent.

Changes in agency organization

State mental health authorities have already been affected and will continue to be affected by the growth of the health plan model of public mental health services. Because decisions about the design and role of these agencies involve historical, administrative, and political considerations, however, it is difficult to be very specific about their future makeup. Nevertheless, as Medicaid services administration becomes a larger part of the state mental health authority role, it seems likely that state decision makers will question the utility of an organizational structure and orientation based on the community model.

In this context, one major organizational choice would seem to be greater integration of the state mental health authority with the larger Medicaid-dominated system of health services administration. Such an arrangement could spread mental health-related functions across organizational areas. Alternatively, such an arrangement might delegate the administration of mental health specialty services to an identifiable mental health entity with responsibility for setting rates and standards and for monitoring services. State mental health authorities might also focus their concern on uninsured individuals and services that fall outside the Medicaid program. These outcomes are by no means certain or necessarily mutually exclusive. It is entirely possible that efforts will be made to limit such changes in many states. These efforts will have the goal of preserving organizational structures and relationships in line with the community model of services delivery.

Changes in data systems and performance measurement

Most state mental health data systems are limited to information about specialty services directly provided or funded by the state mental health authority. Not generally included in these systems is information about mental health services provided by nonspecialty providers or funded by Medicaid outside of state mental health authority administration. Continuation of these arrangements essentially means that program reporting on state mental health services expenditures will characterize a smaller and smaller part of all services supported by public funds. Performance measures oriented to the operations of state mental health authorities will be similarly limited.

For these reasons, states are already beginning to move toward reforming mental health data systems to make them more compatible with, and capable of being integrated with, their state Medicaid data systems. These changes will probably necessitate a movement away from a system that is oriented to describing provider behavior and toward one that can accurately provide individual-level information on services utilization and spending, regardless of payer or provider type. Performance measurement will probably move beyond a focus on services operated or funded by the state mental health authority to encompass critical information about key services, independent of payment source. These changes may be encouraged both by federal efforts to help support such reforms and by demands from interest groups for better information needed to assess issues in the health plan model.

Changes in planning and reporting

Under the health plan model of services delivery, planning and reporting of publicly financed services will increasingly move beyond the parameters dictated by state mental health authorities' budgets and responsibilities. This shift will require acknowledging that the publicly funded system is shared between the state mental health and Medicaid authorities. Such acknowledgment will mean state mental health authorities must accept that their control and direction of the system are limited. It will also mean Medicaid agencies must accept that they have a role in and responsibility for mental health services planning and administration that are independent of but cooperative with those of the state mental health authority.

Efforts to improve state mental health planning to encompass Medicaid services and information will require that state Medicaid authorities produce program reports with the same degree of specificity as those of state mental health authorities. Such efforts will require both types of agencies to reexamine the kinds of program statistics that are most effective for program planning and to modify their reporting systems to produce compatible reports.

Specialty providers

Shifts in the sources and character of financing for community-based providers will increasingly change their mission, characteristics, staffing, and services. First, the shift from grant- or contract-based funding that targets designated providers to an insurance-based funding model will mean that community providers will have less discretion in determining staffing, target populations, and services. Second, although state mental health authorities may still exercise oversight of such providers, Medicaid rules and managed care plan practices also will direct providers' makeup and behavior. Finally, increased competition will require changes in business areas such as records and data systems. In this context, services will be determined more by their ability to generate revenue than by any assessment of community need.

Federal grant programs

Some federal programs aimed at expanding or improving public mental health services may continue to target either state mental health authorities or communities. The increased importance of Medicaid, however, makes it seem likely that more federal effort will be directed to demonstrating and assessing the effects of mental health service innovations within that program. This change in turn suggests that there will be more joint initiatives involving the two federal agencies concerned with Medicaid and mental health services delivery, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Such initiatives are most likely to be directed to Medicaid authorities and to address policy areas such as eligibility, benefits, payment, and utilization management.

Mental health interest groups

The advocacy efforts of mental health interest groups still appear to be most concerned with budgets and programs administered by state mental health authorities. But as these groups understand better the growing role of Medicaid, it is likely that they will shift more of their resources to supporting efforts to influence the policies and spending of Medicaid programs. Nationally, the growing federal share of spending for public mental health services means that advocacy at the federal level will have a greater effect on state and local services than it has in the past.

Interest groups will probably change the content of their advocacy as well as its targets. For the past decade, one area of mental health advocacy has been the promotion of state and federal parity mandates. These mandates have been directed mostly at employer-sponsored health plans. However, the shift in public funding to a health plan model means that design issues traditionally associated with the private sector also become relevant to the public sector. As a consequence, advocates will find that the content of policy debates about public mental health services will increasingly resemble the content of debates about services provided in the private sector.

Conclusions

This article has documented that a change is under way in the organization and financing of state-based public mental health services. This change is not an all-or-nothing one, but rather a shift in the relative importance of two models of organization and financing that have coexisted for decades, the community model and the health plan model. States generally have administrative systems that include at least some features of both models and will probably continue to do so. However, this article has argued that features associated with the health plan model will become increasingly dominant.

To a large degree, the shift toward the health plan model is an unintended consequence of general trends in policy and financing. The shift does not result from any explicit judgment that that model is necessarily superior to the community model as a means of organizing and financing mental health services. Thus arguments about the relative merits of these models for mental health services will have little effect on actual system changes.

The growing dominance of the health plan model means that the community model will become increasingly limited as a basis for understanding and changing public mental health services systems. The failure to recognize this change and its implications will probably have negative consequences. Interest groups that continue to focus primarily on state mental health authority decisions will become progressively more frustrated in their efforts to influence public mental health policy. Measures that generally equate state mental health authority performance with system performance will provide less and less information about the true functioning of the system. System change initiatives that continue to assume that "communities" are the central change agents will decrease in effectiveness.

Efforts may persist that have the goal of preserving organizational structures, relationships, and practices more in line with the community model of services delivery. But the result could be a system that will be limited in its ability to identify and address important policy issues and that may defer major policy decisions to areas of government with limited expertise in mental health issues and services.

For these reasons, individuals and groups that concern themselves with public mental health services policy would best direct their efforts to understanding these changes and their implications. Such understanding will require reconceptualizing problems and proposed solutions as well as changing the perspective from which the public system is viewed. Such a shift will challenge habits of thought that have long shaped discussions of public mental health policy. Nevertheless, this shift in thinking is necessary if the complexities and problems of the new system of organization and financing are to be effectively addressed.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Terry Cline, Ph.D., Michael Fitzpatrick, M.S.W., Melvyn Haas, M.D., Trevor Hadley, Ph.D., Pamela Hyde, J.D., Ted Lutterman, Ph.D., Dave Nelson, M.P.P., and Steven Sharfstein, M.D., for helpful comments on the manuscript.

The author is associate director for organization and financing in the Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 5600 Fishers Lane, Rockville, Maryland 20857 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Sources of state- and locally administered mental health spendinga

a Estimates for 1987 through 1997 are from Coffey and associates (1). Trends for Medicaid and the State Children's Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) were based on spending projections by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for 2000 through 2010 and extended through 2017. Estimates for the federal Mental Health Services Block Grant were extrapolated from its budget growth from 1987 to 2002. Other state- and locally administered spending was extrapolated from the trend for 1987 to 1997.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of two models of organization and financing for state-based public mental health services

1. Coffey RM, Mark T, King E, et al: National Estimates of Expenditures for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment, 1997. SAMHSA pub no SMA-00–3499. Rockville, Md, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment and Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, July 2000Google Scholar

2. Buck JA: Spending for state mental health care. Psychiatric Services 52:1294, 2001Link, Google Scholar

3. Community Action Grants for Service Systems Change. Program announcement (PA) 00–003. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2001Google Scholar

4. Technical Workgroup to the NASMHPD President's Task Force on Performance Indicators: Recommended Operational Definitions and Measures to Implement the NASMHPD Framework of Mental Health Performance Indicators. Draft report. Alexandria, Va, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, December 2000Google Scholar

5. Sixteen State Pilot Study State Mental Health Agency Performance Measures. Alexandria, Va, NASMHPD Research Institute, February 27, 2001Google Scholar

6. Holahan J, Coughlin T, Ku L, et al: Understanding the recent growth in Medicaid spending, in Medicaid Financing Crisis: Balancing Responsibilities, Priorities, and Dollars. Edited by Rowland D, Feder J, Salganicoff A. Washington, DC, AAAS Press, 1993Google Scholar

7. Buck JA, Kiesler CA, Ashman TD, et al: Medicaid limits on support of institutional psychiatric care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 22:573–580, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Manderscheid RW, Atay JE, Hernandez-Cartagena R, et al: Highlights of organized mental health services in 1998 and major national and state trends, in Mental Health, United States, 2000. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ. DHHS pub no (SMA) 01–3537. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 2001Google Scholar

9. Coughlin TA, Ku L, Kim J: Reforming the Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital Program. Health Care Financing Review 22:137–157, 2000Medline, Google Scholar

10. Coughlin TA, Liska D: The Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital Payment Program: Background and Issues. Series A, A-14. Washington, DC, Urban Institute, 1997Google Scholar

11. Smith V, Ellis E, Hogan M: Effect of Medicaid Maximization and Managed Care on Cooperation, Collaboration, and Communication Within State Governments. Lawrenceville, NJ, Center for Health Care Strategies, July 1999Google Scholar

12. The Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2004–2013. Washington, DC, Congressional Budget Office, Jan 2003Google Scholar

13. The Fiscal Survey of States: November 2002. Washington, DC, National Governors Association and National Association of State Budget Officers, 2002Google Scholar

14. State Mental Health Agency Relationship to Medicaid for Funding and Organizing Mental Services. Pub no 02–09. Alexandria, Va, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute, Sept 2002Google Scholar

15. Funding Sources and Expenditures of State Mental Health Agencies, Fiscal Year 2001. Alexandria, Va, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute, May 2003Google Scholar

16. Membership Profile Report. Rockville, Md, National Council of Community Mental Health Centers, 1985Google Scholar

17. Provider Profile Report. Rockville, Md, National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare, 2002Google Scholar

18. Medicaid Managed Care Enrollment Report: Penetration Rates From 1991–1995. Baltimore, Md, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at www.cms.hhs.gov/medicaid/managedcare/mmcss95.aspGoogle Scholar

19. Medicaid Managed Care Enrollment Report: Summary Statistics as of June 30, 2002. Baltimore, Md, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Available at www.cms.hhs.gov/medicaid/managedcare/mmcss02.aspGoogle Scholar

20. State Profiles, 2000, on Public Sector Managed Behavioral Health Care. DHHS pub no (SMA) 00–3432. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2001Google Scholar