Blood-Borne Infections and Persons With Mental Illness: Regular Sources of Medical Care Among Persons With Severe Mental Illness at Risk of Hepatitis C Infection

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: An estimated 19.6 percent of persons with severe mental illness are infected with the hepatitis C virus. Given the pressing need to identify and treat persons with severe mental illness who are at risk of hepatitis C infection and transmission, the authors sought to estimate the proportion of hepatitis C-positive and -negative persons with severe mental illness who have a regular source of medical care. METHODS: Data for this study were obtained from 777 adults with severe mental illness at four diverse geographic sites at which respondents with severe mental illness participated in a structured interview and laboratory testing for HIV infection, AIDS, hepatitis B infection, and hepatitis C infection. RESULTS: In bivariate analyses, 54.2 percent of hepatitis C-positive and 62.5 percent of hepatitis C-negative study participants with severe mental illness had a regular source of medical care. In multivariate analyses in which potential confounders were statistically controlled for, hepatitis C-positive persons with severe mental illness were less than half as likely as hepatitis C-negative persons to have a regular source of care. Being older, married, insured, or employed or having self-reported health problems increased the likelihood of receiving care. Being black or male or living in a community with high exposure to community violence lowered those odds. CONCLUSION: There is an urgent need to improve access to medical care for persons with severe mental illness, especially those who may be at high risk of or are already infected with the hepatitis C virus.

The troubling findings that an estimated 20 percent of persons with severe mental illness show laboratory evidence of hepatitis C infection (1) raises important questions about the integration of psychiatric and medical care aimed at hepatitis C disease management, education, and risk behavior reduction for this population.

Little is known about access to medical care or the extent of screening for hepatitis C risk factors or infection among persons with severe mental illness. These patients may be slow to recognize developing illness or may not seek care when they become symptomatic (2,3,4). The historic division between medical and specialty mental health service sectors also means that patients with severe mental illness are most likely to receive care in specialty—often public-sector—mental health programs, where little general medical care is provided.

Few studies have examined receipt of medical care among persons with severe mental illness. One study in an urban health center found that women with severe mental illness were equally as likely as those without mental illness who were living in poverty to receive preventive health care (5). However, 13 percent of the women with severe mental illness had no primary health care provider. The study also found that among women both with and without mental illness, a history of physical or sexual abuse was associated with less frequent receipt of preventive services. Another study used data from the 1984 National Health Interview Survey (6) to examine barriers to receipt of medical services among persons reporting psychiatric disorders. Persons with a psychiatric disorder were no less likely than those without to be uninsured or to have a primary care provider. However, they were twice as likely to report delays in seeking care because of cost or inability to obtain needed care. Of those who reported a disorder, 14.8 percent reported lacking a regular medical provider. Numerous studies have demonstrated mortality rates that are at least twice as high among persons with severe mental illness, with a life expectancy ten years less than that of the general population. Some authors have attributed these poor health outcomes to clients' lack of regular medical care (7,8,9,10,11,12).

In a recent study, we reported alarming rates of hepatitis C infection—20 percent—in a large, multisite sample of persons with severe mental illness (1). Given the pressing need to identify and treat persons with severe mental illness who are at risk of hepatitis C infection and transmission, we used data from the same study to estimate the proportion of hepatitis C-positive and -negative persons with severe mental illness who have a regular source of medical care.

Methods

Data for this study were obtained from 777 adults with severe mental illness at four of the diverse geographic sites participating in the full five-site study and described in this issue of Psychiatric Services. As discussed by Rosenberg and colleagues (1,13), the patients from North Carolina could not be included in the analyses.

As in the full five-site study sample of 969 persons, most participants in this study were male (67.7 percent), with a mean±SD age of 42.3±10.2 years; 51.6 percent of respondents were white, 38.6 percent were African American, 3.2 percent were Hispanic, and 6.6 percent were of another race or ethnicity. A majority of the participants had never married (53.3 percent), 12.4 percent were married or cohabiting, and 34.3 percent were divorced, widowed, or separated. One-third of the participants (33.8 percent) reported having less than a high school education, 28.7 percent reported completing high school or obtaining a graduate equivalency diploma, and 37.4 percent reported some postsecondary education. Only 16.7 percent of the participants reported current employment. The mean monthly income of the participants was $929.62±779.20. Nearly half of the participants (47.3 percent) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, 18.5 percent had schizoaffective disorder, 14.5 percent had bipolar disorder, 12.8 percent had major depression, and 6.9 percent had other diagnoses. Substance abuse was identified among 45.8 percent of participants.

Measures

Demographic characteristics studied included age, gender, race, marital status, and residential status.

Psychiatric diagnoses were obtained from chart review and all available clinical data. For the analyses reported here, diagnoses were coded into two categories: schizophrenia-spectrum diagnoses and other diagnoses. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) was used to assess symptoms (14,15). The Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument (DALI), an instrument specifically designed to identify substance use disorders among persons with severe mental illness (16), was used to screen for substance abuse. Functional impairment was measured with the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (17). Medication noncompliance was self-reported.

Measures of health care resources and barriers included insurance coverage, employment, education level, and income from all sources by quartile. Respondents were also asked about financial and other barriers to obtaining health care. The number of reported barriers was summed to create a scale of barriers to physical health care.

The participants were asked whether a physician had ever given them a diagnosis of any of the major classes of physical health problems. Participants were also tested for certain sexually transmitted or blood-borne infectious diseases, including hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV. A scale was created by adding the number of medical problems the respondents reported, with "1" added if they tested positive for any infectious disease. The participants also provided their self-reported health status on a 4-point scale from poor to excellent. The serologic test for hepatitis C was also included as a separate variable.

Recent physical abuse and sexual abuse was assessed by asking participants a detailed series of questions about incidents that may have happened in the previous year. Sexual abuse was assessed with the Sexual Abuse Exposure Questionnaire (18). The respondent's exposure to a violent community environment was assessed with the Community Exposure to Violence Instrument (19). A community violence scale was created by adding the number of positive responses to these questions about violence. Sex- or drug-related risk behaviors were assessed by asking respondents a detailed series of questions about their behavior in these areas over their lifetime.

Having a regular source of medical care was defined as self-report of a physician or another health care professional usually seen for medical care.

Analyses

Logistic regression analyses were used to examine the relative effects of demographic factors, clinical characteristics, resources and barriers, health status, and community and personal violence on the likelihood of having a regular source of medical care. The logistic regression estimated the average change in the odds of having a regular source of medical care associated with each unit change in the predictor variables. Confidence intervals above 1 indicate a significant positive effect at p<.05, whereas confidence intervals below 1 indicate a significant negative effect at p<.05. The data for the analyses reported in this article are cross-sectional.

To obtain a sufficiently large sample for these analyses, samples were pooled from all four sites. However, these samples differed from each other and from national estimates of the distributions of some variables among persons with severe mental illness that could be associated with having a regular source of medical care—for example, age and co-occurring substance abuse.

To compensate for this potential bias, each sample was independently weighted to match the age and substance abuse distributions found in the National Institute of Mental Health National Comorbidity Study (NCS), a nationally representative probability sample, for respondents with psychotic or major mood disorders who reported a psychiatric hospitalization or use of specialty mental health services in the previous six months (20).

Because study participants were clustered by site, the observations in the pooled and weighted multisite data were not truly independent. Thus Stata 6.0 was used to provide robust variance estimates that account for the effects of clustering and weighting (21,22). Specifically, the population weight function of Stata regression models uses a sandwich estimator specified by the "robust" function. Thus all reports of statistical significance in the analysis presented in this article are based on weighted data and control for site-specific effects.

Results

Health problems

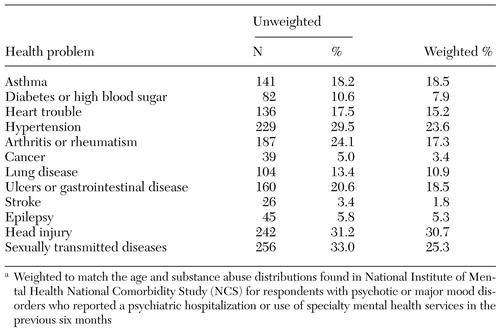

The health problems reported by the study participants are listed in Table 1, unweighted and weighted. Head injuries and sexually transmitted diseases were reported by more than a quarter of the participants.

Bivariate results

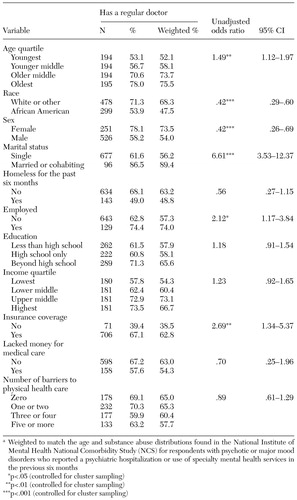

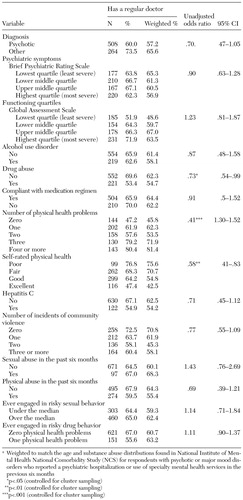

The bivariate associations between having a regular source of medical care and demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, clinical characteristics, resources and barriers, health status, and community and personal risk factors are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The proportion of participants in each category is presented for both unweighted and weighted distributions. Tests of significance for each bivariate association were conducted by using the weighted data with robust estimates of variance adjusted for clustering by site.

Only 54.2 percent of hepatitis C-positive compared with 62.5 percent of hepatitis C-negative persons with severe mental illness had a regular source of medical care. Being younger, African American, male, and single were all independently associated with a lower likelihood of having a regular source of medical care. The only clinical characteristic significantly associated with a lower likelihood of having a regular source of care was a positive screen for drug abuse on the DALI, although the screen for alcohol abuse was not a significant factor. Having employment and insurance coverage was associated with having a regular provider, although none of the barriers were significant predictors. A greater number of medical problems and poorer self-reported health were also associated with having a regular provider. None of the community and personal risk factors were significantly associated with having a regular source of care.

Although fewer hepatitis C-positive participants than other participants with severe mental illness had a regular source of care, this trend was not significant. Potential interactions with other demographic or need factors may have suppressed the significance of this relationship. Thus this relationship may be better examined in multivariate analyses with potential confounders controlled for.

Multivariate models

We performed stepwise logistic regression analyses using variables in each domain separately to predict the likelihood of having a regular source of care.

The full distributions on age, functioning, symptoms, and barriers were used in all multivariate models, even though these variables are presented in a categorical format in Tables 2 and 3. Income was divided into quartiles because of its skewed distribution.

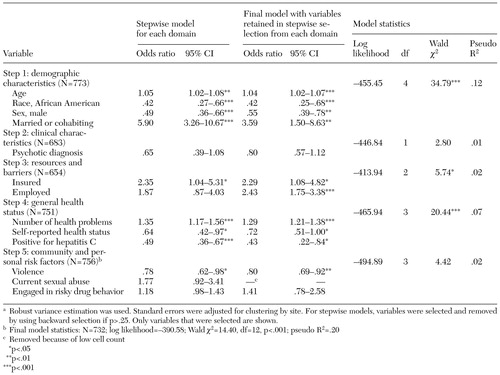

The results of these stepwise regressions and the final all-domain model are summarized in Table 4. Of the demographic characteristics, age, race, gender, and marital status were retained in the stepwise selection. Also retained were clinical variables (psychotic diagnosis), resources and barriers (insurance and employment), general health indicators (number of health problems, self-reported health status, and hepatitis C status), and personal and community risk factors (exposure to community violence and risky drug behaviors). Current sexual abuse met the initial significance criteria but had to be excluded because of insufficient cell sample size.

The final, all-domain regression model was highly significant (p<.001) and explained nearly 20 percent of the variance in the likelihood of having a regular source of care. Being older or married was associated with a greater likelihood of having a regular source of care, whereas being black or male lowered the likelihood. None of the clinical characteristics was significantly associated with having a regular source of care, whereas having insurance and being employed increased the odds of having a regular source of care. Respondents who had more health problems were more likely to report having a regular source of care, whereas those who lived in a community with more community violence were less likely to have a regular source of care. The full model showed that persons with severe mental illness with hepatitis C infection were less than half as likely as other persons with severe mental illness to have a regular source of care (odds ratio=.43; 95 percent confidence interval=.22 to .84).

Discussion and conclusions

Persons with severe mental illness who lack a regular source of medical care may often gain access to care through urgent or emergency care settings in which hepatitis C screening, disease management, and education about risk-behavior reduction are unlikely to occur. Our analyses showed that only 54.2 percent of persons with both severe mental illness and hepatitis C had a provider from whom they usually received care. Furthermore, when other potential predictors of source of care were controlled for, we found that persons with both severe mental illness and hepatitis C were less than half as likely as those with severe mental illness alone to have a regular source of care. These hepatitis C-infected individuals are in dire need of efforts to engage them in continuity of medical care, especially if they are to receive prolonged antiviral treatment and risk-reduction interventions.

Other predictors of having a usual source of care are also noteworthy. It is not surprising that older persons are more likely to have a regular source of care, because persons acquire multiple medical problems as they age. Disconcerting is the lower likelihood of care among African Americans and males, which suggests that special efforts are needed to engage these patient groups. The higher likelihood of care among persons who are married or cohabiting may suggest greater underlying personal stability and the presence of someone to encourage regular use of care.

Our analyses showed that living in a crime-ridden neighborhood decreased the odds of care. Although one explanation might be that fear of venturing out discourages care seeking, the finding also suggests that living in a chaotic environment impedes regular health practices. Interestingly, risky drug behavior was not associated with lack of a regular source of care. However, such behavior was infrequently reported, which limited statistical power to estimate associations with a regular source of care.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. The extent of screening for and identification of hepatitis C in mental health settings was not evaluated. Anecdotally, we have found little recognition of the need to screen for hepatitis C by mental health providers and limited resources to expand the scope of their work to include such screening. Integrating medical and psychiatric care by developing in-house primary care capacity in mental health centers or improving links between psychiatric and medical clinics is critical. Lehman (23) suggested that publicly funded managed care plans should provide integration of primary and mental health specialty care to ensure that patients receive appropriate medical care and to ensure early detection and intervention.

A second limitation of this study was the fact that it was cross-sectional. Identification of hepatitis C infection during the study may well have stimulated improved medical coordination for hepatitis C-positive individuals and raised awareness of the need for hepatitis C screening among mental health providers at the participating study sites. As a result, some of these hepatitis C-positive individuals might have been identified and referred for care while the study was under way, increasing the likelihood of care.

We have reported rates of care for persons with a previous diagnosis of hepatitis C infection as well as those without. These rates may be quite different, because we lack data on how many participants in this study already knew their hepatitis C status. If many of the participants who were infected with hepatitis C were already aware of their hepatitis C status and had been engaged in medical treatment, this would likely have attenuated our findings of a lower likelihood of regular care among the combined group of those with a previous diagnosis and those without. That is, the low likelihood of care may actually understate the problem among persons who have not yet received a diagnosis of hepatitis C infection.

Dr. Swartz, Dr. Swanson, and Mr. Hannon are affiliated with the services effectiveness research program in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of Duke University Medical Center, Box 3173, Durham, North Carolina 27710 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Bosworth is with the Department of Veterans Affairs and with the departments of psychiatry and medicine at Duke University Medical Center. Dr. Osher is with the Center of Behavioral Health, Justice, and Public Policy at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore. Dr. Essock is with the department of psychiatry of Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. Dr. Rosenberg is with New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center at Dartmouth Medical School in Hanover, New Hampshire. This article is part of a special section on blood-borne infections among persons with severe mental illness.

|

Table 1. Health problems reported by 777 persons with severe mental illness at risk of hepatitis C infectiona

a Weighted to match the age and substance abuse distributions found in National Institute of Mental Health National Comorbidity Study (NCS) for respondents with psychotic or major mood disorders who reported a psychiatric hospitalization or use of specialty mental health services in the previous six months

|

Table 2. Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of 777 persons with severe mental illness at risk of hepatitis C infection and bivariate associations with having a regular doctora

a Weighted to match the age and substance abuse distributions found in the National Institute of Mental Health National Comorbidity Study (NCS) for respondents with psychotic or major mood disorders who reported a psychiatric hospitalization or use of specialty mental health services in the previous six months

|

Table 3. Health-related characteristics of 777 persons with severe mental illness at risk of hepatitis C infection and bivariate associations with having a regular doctora

a Weighted to match the age and substance abuse distributions found in National Institute of Mental Health National Comorbidity Study (NCS) for respondents with psychotic or major mood disorders who reported a psychiatric hospitalization or use of specialty mental health services in the previous six months

|

Table 4. Predictors of having a regular doctor in a sample of persons with severe mental illness at risk of hepatitis C infectiona

a Robust variance estimation was used. Standard errors were adjusted for clustering by site. For stepwise models, variables were selected and removed by using backward selection if p>.25. Only variables that were selected are shown.

1. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al: Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 91:31-37, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hall RCW, Gardner ER, Stickney SK, et al: Physical illness manifesting as psychiatric disease. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:989-995, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hoffman RS, Koran LM: Detecting physical illness in patients with mental disorders. Psychosomatics 25:654-659, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Jeste DV, Gladsjo JA, Lindamer LA, et al: Medical comorbidity in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 22:413-430, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Steiner JL, Hoff RA, Moffett C, et al: Preventive health care for mentally ill women. Psychiatric Services 49:696-698, 1998Link, Google Scholar

6. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA: Mental disorders and access to medical care in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1775-1777, 1998Link, Google Scholar

7. Black DW: Iowa record-linkage study: death rates in psychiatric patients. Journal of Affective Disorders 50:277-282, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Dembling B: Mental disorder as a contributing cause of death in the U.S. in 1992. Psychiatric Services 48:45, 1997Link, Google Scholar

9. Dembling BP, Chen DT, Vachon L: Life expectancy and causes of death in a population treated for serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:1036-1042, 1999Link, Google Scholar

10. Felker B, Yazel JJ, Short D: Mortality and medical comorbidity among psychiatric patients: a review. Psychiatric Services 47:1356-1363, 1996Link, Google Scholar

11. Harris EC, Barrablough B: Excess mortality of mental disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 173:11-53, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Stroup TS, Gilmore JH, Jarskog LF: Management of medical illnesses in persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Annals 30:35-40, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Rosenberg SD, Swanson JW, Wolford GL, et al: The Five-Site Health and Risk Study of blood-borne infections among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:827-835, 2003Link, Google Scholar

14. Faustman WO, Overall JE: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, in The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and outcomes Assessment. Edited by Maruish MW. Mahwah, NJ, Erlbaum, 1999Google Scholar

15. Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-812, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Rosenberg SD, Drake RE, Wolford GL, et al: Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument (DALI): a substance use disorder screen for people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:232-238, 1998Abstract, Google Scholar

17. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al: The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766-771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Ryan SW: Psychometric analysis of the Sexual Abuse Exposure Questionnaire. Dissertation Abstracts International 54:2268, 1992Google Scholar

19. Gaba RJ: Psychometric properties of the survey of children's exposure to community violence: screening version. Dissertation Abstracts International 57:4774, 1997Google Scholar

20. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Stata Reference Manual, release 6. College Station, Tex, Stata Press, 1999Google Scholar

22. Stata User's Guide. College Station, Tex, Stata Press, 1999Google Scholar

23. Lehman AF: Quality of care in mental health: the case of schizophrenia. Health Affairs 18 (5):52-65, 1999Google Scholar