Palliative and Aggressive End-of-Life Care for Patients With Dementia

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: The goals of this study were to establish the frequency of palliative and aggressive treatment measures among patients with and without dementia during the last six months of life, to identify relationships between the severity of dementia and aggressive and palliative care, and to determine whether treatment patterns have changed over time. METHODS: Antemortem data for 279 patients with dementia and 24 control patients who were brought for autopsy in chronic care facilities between 1985 and 2000 were reviewed. The severity of dementia was defined by scores on the Clinical Dementia Rating scale. Data on use of systemic antibiotics (designated as an aggressive treatment measure) and on use of narcotic and nonnarcotic pain medications and nasal oxygen (defined as palliative measures) were collected from medical charts. RESULTS: Fifty-three percent of the patients with dementia and 46 percent of those without dementia had received systemic antibiotics. Fourteen percent of the patients with dementia and 38 percent of those without dementia had received narcotic pain medications. The prevalence of aggressive and palliative measures did not vary significantly with the severity of dementia. Eleven percent of the patients with dementia who died between 1991 and 1995 and 18 percent of those who died between 1996 and 2000 had received narcotic pain medications in the last six months of their lives. CONCLUSIONS: Use of systemic antibiotics is prevalent in the treatment of patients with end-stage dementia, despite the limited utility and discomfort associated with the use of these agents. That patients with severe dementia and those with milder cognitive impairment received similar treatment may be contrary to good clinical practice, given the poor prognosis of patients with severe dementia.

Alzheimer's disease is a progressive form of dementia (1). During the severe stage of the illness, patients lose the ability to communicate their needs and require significant assistance in activities of daily living. Physical consequences of the progression of dementia predispose persons with advanced Alzheimer's disease to infection and fever (2), especially aspiration pneumonia (3,4) and urinary tract infections (5,6). There is no accepted standard treatment for the medical consequences of advanced dementia. The use of aggressive treatment, such as antibiotics and enteral tube feeding, appears to be prevalent (7).

However, there is substantial evidence that an aggressive medical approach is of limited efficacy. End-stage dementia has been associated with a poor prognosis and a limited life expectancy, which are not improved by invasive procedures (8). Aggressive treatment of infection does not improve survival rates among persons with severe dementia (2) and has been associated with accelerated progression of the severity of dementia (9). Antibiotics and other aggressive measures, although they probably do not improve survival, are associated with numerous deleterious outcomes, including renal failure and ototoxicity, allergic or drug reactions, rash, diarrhea, blood dyscrasias, antibiotic resistance, use of intravenous lines and mechanical restraints, prolonged time to death, and increased costs (2,7,10,11,12).

It is well established that people who have Alzheimer's disease and related dementias receive analgesia less frequently than those who are cognitively intact, even when they have similar medical disease burdens (7,8,13,14,15,16). It has been suggested that the low use of pain medication for patients with dementia is attributable not to lower pain levels but to the deterioration of verbal and nonverbal communication, which means that pain goes unreported and unrecognized and thus undertreated (17,18,19,20). The frequency of pain reporting diminishes with the severity of dementia (21), and noncommunicative patients with dementia are at risk of having their pain identified much less frequently than communicative patients (22).

The futility and discomfort of aggressive treatments, combined with the underrecognition and undertreatment of pain among patients with severe dementia, support the use of palliative care for advanced dementia (23). Among patients with severe dementia, comfort care has been associated with lower levels of discomfort (12). Furthermore, limited use of antibiotics has not been associated with increased mortality (2,23), and aggressive treatment of infections has not been shown to alter underlying disease processes (9).

Most of the literature on the care of patients with Alzheimer's disease has not focused on end-of-life experiences. Furthermore, little is known about how the severity of dementia is correlated with the use of aggressive or palliative care measures. The goals of this study were to establish the prevalence of aggressive and palliative treatment measures in a well-characterized population of patients with dementia who were sent for autopsy, the relationships of aggressive and palliative care to the severity of dementia, and whether patterns of palliative and aggressive treatment of patients with dementia have changed over time.

Methods

All the patients in the study were living in chronic care facilities at the time of their death. Antemortem data for 279 patients with dementia and 24 control patients who were brought for clinical autopsy between 1985 and 2000 were reviewed. Although the staff of an Alzheimer's disease research center were responsible for conducting autopsies and postmortem chart reviews, all the patients had been receiving standard clinical care until the time of their death. The chronic care facilities were clinical rather than research settings, and all patients were approached equally about the possibility of autopsy. About 10 percent of the patients or a member of their family consented to an autopsy. Informed consent was obtained for all autopsies, and the study was approved by all relevant institutional review boards.

For all autopsies, semistructured chart reviews were conducted by either a physician or a research nurse. Data on the use of systemic antibiotics, narcotic and nonnarcotic pain medications, and nasal oxygen during the last six months of life were used to assess the frequency of aggressive and palliative treatment. Aggressive treatment was defined as use of antibiotics, and palliative care was defined as the use of narcotic or nonnarcotic pain medication or nasal oxygen.

The severity of dementia during the last six months of life was assessed with a chart review that yielded a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) score (24). Possible scores on the CDR range from 0 to 5, with higher scores representing more severe dementia. Ratings of dementia made during clinical interviews and chart-review-generated CDR scores are highly correlated (25). To assess the relationship between the severity of dementia and the prevalence of either aggressive or palliative interventions, the patients with dementia were divided into three groups on the basis of their CDR scores: .5 to 1, mild dementia (52 patients); 2, moderate dementia (42 patients); and 3 to 5, severe dementia (185 patients).

To determine whether patterns of palliative and aggressive care among patients with dementia have changed over time, the patients in our sample were divided into three cohorts based on date of death. Nineteen of the patients died between 1985 and 1990, inclusive; 124 between 1991 and 1995; and 136 between 1996 and 2000.

Data were analyzed with SPSS 10. Chi square tests were used to compare categorical variables, and t tests were used to compare continuous variables. Differences were considered to be significant if the p value was less than .05.

Editor's note: This paper is part of a series of papers by, about, and for residents edited by Avram H. Mack, M.D. Prospective authors—current residents, fellows, and faculty members—should contact Dr. Mack at the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Unit 74, New York, New York 10032; e-mail, [email protected].

Results

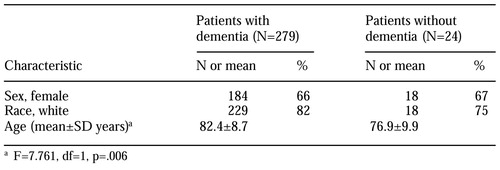

The study patients were residents of 30 different chronic care facilities before their death. A total of 218 patients (72 percent) lived in one facility. Basic demographic data on the study sample are presented in Table 1. Multiple physicians were involved in patient care at the largest facility. No significant differences were noted between the patients who were autopsied and those who were not in patterns of care across sites or in race, sex, age, educational level, occupation, or medical burden.

Medical burden of the sample

The mean±SD number of medical diagnoses per patient was 10.5±1.4. No significant differences were observed in the number or types of diagnoses between patients with and without dementia or across severity or death cohorts. The five most common medical diagnoses were coronary artery disease (143 patients, or 47 percent), pneumonia (128 patients, or 42 percent), urinary tract infections (90 patients, or 30 percent), hypertension (99 patients, or 33 percent), and congestive heart failure (89 patients, or 29 percent).

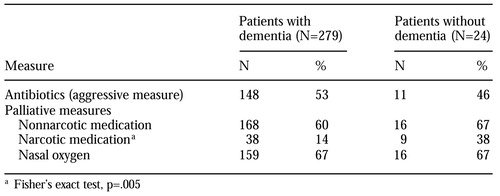

The prevalence of palliative and aggressive measures among the patients with dementia and the control patients is summarized in Table 2. Use of antibiotics was common in both groups. The patients with dementia were significantly less likely to have received narcotic pain medication.

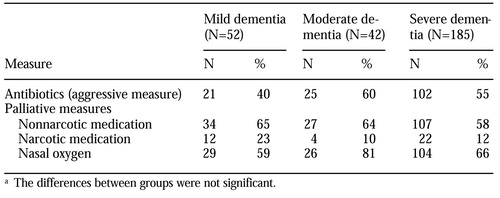

The prevalence of palliative and aggressive measures across severity groups of patients with dementia is summarized in Table 3. No significant differences were found in the use of any measure. Use of antibiotics was common among patients with dementia, whereas use of narcotic pain medication was relatively infrequent.

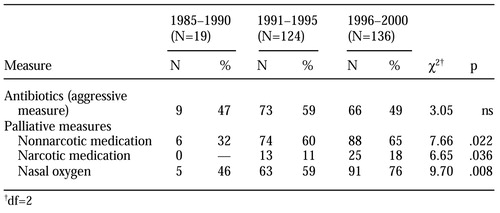

The prevalence of palliative and aggressive measures in the three death cohorts is summarized in Table 4. Use of nonnarcotic and narcotic pain medications as well as nasal oxygen was significantly more prevalent in the 1996-2000 cohort. Use of antibiotics did not vary significantly over time.

Discussion

We found a high prevalence of systemic antibiotic use (53 percent) and a relatively low rate of use of narcotic pain medications (14 percent) among patients with dementia who were living in chronic care facilities during the last six months of their lives. These findings confirm, in a large and well-characterized patient population, the aggressive nature of treatment of persons with dementia that has been reported in other studies (7). In particular, patients with severe dementia were as likely as patients without dementia to have received antibiotics. Although antibiotic treatment of intercurrent infections among patients with mild or moderate dementia may reduce mortality, such treatment may not improve survival among those who have more severe cognitive impairment (2).

Possible reasons for the high prevalence of antibiotic treatment include a lack of advance directives (8), inadequate training of physicians in discussing end-of-life decisions (26), and physicians' uncertainty about the course of dementia. Luchins and colleagues (27) have developed an algorithm that has excellent predictive validity for identifying patients with dementia who have a six-month prognosis. Their criteria include National Hospice Organization criteria and Functional Assessment Staging.

Although patients with dementia are treated aggressively in conventional hospital settings, hospice programs for this patient population are underutilized at the national level (28), despite the fact that 90 percent of family and professional caregivers view hospices as appropriate for patients with end-stage dementia (29). Hospice programs were originally developed for patients with cancer, and only a minority of hospice facilities have served persons with dementia. Over the past few years, these services have become more widely available for patients with dementia (30). However, Medicare reimbursement for hospice services for dementia is below that for hospice services for other conditions (31).

Patients who had dementia received significantly less narcotic medication than those who did not have dementia, both in the sample as a whole and when we controlled for the presence of potentially painful conditions. This finding confirms numerous reports that persons with cognitive impairment receive analgesia less frequently than those who are cognitively intact (7,8,13,14). Scales have been developed for assessing pain and discomfort among patients with Alzheimer's disease (32,33) in order to enhance the recognition and treatment of pain in this population.

Among patients with dementia, no significant differences were found in the use of pain medication across severity groups. The analgesic needs of patients with dementia have been described as stage independent (13), indicating that equivalent use of analgesia across severity cohorts is a reasonable approach. It has been suggested that patients who have dementia experience pain very differently from those who are cognitively intact. In studies of patients with dementia and poor cognition, patients with Alzheimer's disease were found to have a stronger tolerance for pain than patients who did not have dementia (34,35). Because cognitive difficulties exist along a broad continuum from mild cognitive impairment to severe dementia, the relationship between the experience and the presentation of pain by patients with dementia may be complex.

The administration of nonnarcotic and narcotic pain medications and nasal oxygen has increased over the past 15 years. This trend may be attributable to numerous reports that have called attention to the undertreatment of pain among persons with cognitive impairment (36) and the need for palliative care for patients with dementia (12). Although the use of narcotic pain medication among patients with dementia has increased significantly, the use of analgesics is still significantly below that observed among patients who do not have dementia. A broader inquiry into the full range of decisions surrounding end-of-life care—such as the use of intravenous fluids, parenteral feeding, and advance directives—is needed.

The use of antibiotics did not change significantly over the three time cohorts we examined. Thus, although information about pain management may have affected clinical practice during that time, it seems that data on the judicious use of antibiotics has not had a similar impact. Research during the past five years has similarly shown a high prevalence of antibiotic use (7) and of burdensome procedures in general (8) among patients with dementia.

Greater use of hospices by patients with dementia may constitute good patient care and good public policy. Facilities may consider education programs for family and staff that focus on the hospice options available to patients. Staff may also be encouraged to actively revisit advance-directive discussions with patients and their families throughout the course of illness. A more favorable Medicare reimbursement policy for hospice services may also be warranted.

The use of selected variables as proxies for palliative and aggressive care does not capture all aspects of the larger domains of clinical decision making. Because participation in this study required that the patient or caregiver provide consent to autopsy, selection bias may have limited the generalizability of the results to the general population.

Conclusions

Administration of antibiotics to patients with dementia who were living in chronic care facilities during the last six months of their lives was prevalent, despite the limited utility and discomfort associated with these measures. That patients with severe dementia received similar treatment to those with milder impairment and elderly patients without dementia, given the poor prognosis of end-stage dementia, may be contrary to good clinical practice. Although pain management may be improving, the practice of using antibiotics does not appear to have changed. An ongoing discussion of the medical and ethical implications of end-of-life care of persons with dementia is needed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant AG-02219 from the National Institute on Aging. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Sean Morrison, M.D., and Pervaiz Q. Qureshi, M.D.

The authors are affiliated with the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. Send correspondence to Mr. Evers at 3 Karen Court, Newburgh, New York 12550 (e-mail, [email protected]). Part of this research was presented as a poster at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association held May 5-10, 2001, in New Orleans.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of patients with and without dementia who were living in chronic care facilities during the last six months of life

|

Table 2. Prevalence of palliative and aggressive treatment measures among patients with and without dementia who were living in chronic care facilities during the last six months of life

|

Table 3. Prevalence of palliative and aggressive treatment measures among 279 patients with dementia who were living in chronic care facilities during the last six months of life, by severity cohorta

a The differences between groups were not significant

|

Table 4. Prevalence of palliative and aggressive treatment measures among 279 persons with dementia who were living in chronic care facilities during the last six months of life, by death cohort

1. Tariot PN: Alzheimer disease: an overview. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 8(suppl 2):S4-S11, 1994Google Scholar

2. Fabiszewski KJ, Volicer BJ, Volicer L: Effect of antibiotic treatment on outcome of fevers in institutionalized Alzheimer patients. JAMA 263:3168-3172, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Campbell-Taylor I, Fisher RH: The clinical case against tube feeding in palliative care of the elderly. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 35:1100-1104, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Volicer L, Seltzer B, Rheaume Y, et al: Eating difficulties in patients with probable dementia of the Alzheimer type. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 2:169-176, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Parulkar BJ, Barrett DM: Urinary incontinence in adults. Surgical Clinics of North America 68:945-963, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lipsky BA: Urinary tract infections in men: epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Annals of Internal Medicine 110:138-150, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Ahronheim JC, Morrison RS, Baskin SA, et al: Treatment of the dying in the acute care hospital. Archives of Internal Medicine 156:2094-2100, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Morrison RS, Siu AL: Survival in end-stage dementia following acute illness. JAMA 284:47-52, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Hurley AC, Volicer BJ, Volicer L: Effect of fever-management strategy on the progression of dementia of the Alzheimer type. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 10:5-10, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hurley AC, Volicer BJ, Mahoney MA, et al: Palliative fever management in Alzheimer patients: quality plus fiscal responsibility. Advances in Nursing Science 16(1):21-32, 1993Google Scholar

11. Hurley AC, Mahoney MA, Volicer L: Comfort care in end-stage dementia: what to do after deciding to do no more, in Controversies in Ethics in Long-Term Care. Edited by Olson E, Chichin ER, Libow L. New York, Springer, 1995Google Scholar

12. Volicer L, Collard A, Hurley A, et al: Impact of special care unit for patients with advanced Alzheimer's disease on patients' discomfort and cost. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 42:597-603, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Scherder EJ, Bouma A: Is decreased use of analgesics in Alzheimer disease due to a change in the affective component of pain? Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 11:171-174, 1997Google Scholar

14. Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, et al: Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. JAMA 279:1877-1882, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Marzinski LR: The tragedy of dementia: clinically assessing pain in the confused nonverbal elderly. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 17:25-28, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Horgas AL, Tsai P: Analgesic drug prescription and use in cognitively impaired nursing home residents. Nursing Research 47:235-242, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Ferrell BA, Ferrell BR, Rivera L: Pain in cognitively impaired nursing home patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 10:591-598, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Lucca U, Tettamanti M, Forloni G, et al: Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug use in Alzheimer's disease. Biological Psychiatry 36:854-856, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kempler D: Lexical and pantomime abilities in Alzheimer's disease. Aphasiology 2:147-159, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Asplund K, Jansson L, Norberg A: Facial expressions of patients with dementia: a comparison of two methods of interpretation. International Psychogeriatrics 7:527-534, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Parmelee PA, Smith B, Katz IR: Pain complaints and cognitive status among elderly institution residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 41:517-522, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Sengstaken EA, King SA: The problem of pain and its detection among geriatric nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 41:541-544, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Volicer L, Rheaume Y, Brown J, et al: Hospice approach to the treatment of patients with advanced dementia of the Alzheimer type. JAMA 256:2210-2213, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, et al: A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. British Journal of Psychiatry 140:566-572, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Haroutunian V, Purohit DP, Perl DP, et al: Neurofibrillary tangles in nondemented elderly subjects and mild Alzheimer disease. Archives of Neurology 56:713-718, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Meier DE, Morrison RS, Cassel CK: Improving palliative care. Annals of Internal Medicine 127:225-230, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P, Murphy K: Criteria for enrolling dementia patients in hospice. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 45:1054-1059, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Hanrahan P, Luchins DJ: Access to hospice care for end-stage dementia patients: a national survey of hospice programs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 43:56-59, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P: What is the appropriate level of health care for end-stage dementia patients? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 41:25-30, 1993Google Scholar

30. Stuart B: The NHO Medical Guidelines for Non-Cancer Disease and local medical review policy: hospice access for patients with diseases other than cancer. Hospice Journal 14:139-154, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Buchanan RJ: Medicaid policies for the hospice care needed by people with Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration 20:348-388, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

32. Morrison RS, Ahronheim JC, Morrison GR, et al: Pain and discomfort associated with common hospital procedures and experiences. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 15:91-101, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Kovach CR, Weissman DE, Griffie J, et al: Assessment and treatment of discomfort for people with late-stage dementia. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 18:412-419, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Benedetti F, Vighetti S, Ricco C, et al: Pain threshold and tolerance in Alzheimer's disease. Pain 80:377-382, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Porter FL, Malhotra KM, Wolf CM, et al: Dementia and response to pain in the elderly. Pain 68:413-421, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Cook AK, Niven CA, Downs MG: Assessing the pain of people with cognitive impairment. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 14:421-425, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar