Stigma as a Barrier to Recovery: The Extent to Which Caregivers Believe Most People Devalue Consumers and Their Families

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The extent to which 461 caregivers of persons with serious mental disorders believed that most people devalue consumers and their families was assessed, and the magnitude of the relationships between these beliefs and the diagnostic status of consumers was estimated. METHODS: Caregivers of 180 consumers with schizophrenia, major depression, or bipolar disorder and caregivers of 281 consumers with bipolar disorder or schizoaffective disorder, manic type, completed a 15-item instrument comprising two scales: eight of the 15 items operationally defined the devaluation of individual consumers, and seven items operationally defined the devaluation of consumers' families. RESULTS: No significant differences were observed between the two samples on the two devaluation scales or on 14 of the 15 items that constituted the scales. About 70 percent of all caregivers indicated a belief that most people devalue consumers, and 43 percent expressed a belief that most people also devalue the families of consumers. CONCLUSIONS: Strong evidence from previous research indicates that the caregiving role is very demanding, is frequently distressing, and may be harmful to health and injurious to one's quality of life. The addition of a community that is perceived to be rejecting makes life even more difficult for the caregivers and families of people with serious mental disorders. The development and implementation of effective interventions to create more supportive and understanding communities would be a challenging and worthwhile endeavor.

It has been extensively documented that caregivers of persons who have serious and persistent mental disorders— "consumers"—must successfully cope with many challenging problems in order to provide good care. The demands of the caregiving role may result in periods of severe stress for the caregiver, which, under certain conditions, develops into symptoms of demoralization, depression, anxiety, grief, or some form of physical disorder (1,2,3,4,5,6). Informed, understanding, and supportive communities are needed in which caregivers and consumers can develop rewarding interpersonal relationships with members of the community. These relationships would enhance the quality of the lives of caregivers, consumers, and involved community residents.

However, there are impediments to the development of such ideally conceived communities, rooted in the negative perceptions of many people in this country. Several recent studies have shown that the general public associates violent behavior with people who have a serious mental illness alone or in combination with a substance use disorder. For example, in a representative sample of 1,507 adults who were living in noninstitutional housing in the United States, 60 percent agreed with the statement, "You cannot tell what people who have been mentally ill will do from one minute to the next," 60 percent believed that it was "only natural to be afraid of a person who is mentally ill," and 70 percent believed that "although some people who have been patients in mental hospitals may seem all right, it is important to remember they may be dangerous" (7).

In a recent survey of a representative sample of 1,444 adults who were living in noninstitutional housing in the United States, 61 percent of the respondents indicated that a person who was described in an accompanying vignette as having symptoms of schizophrenia would be "likely" or "very likely" to do something violent toward other people (8). For a person described as having symptoms of depression, the percentage was 33 percent; for a person with alcohol dependence, 71 percent; for a person with cocaine dependence, 87 percent; and for a "troubled person," 17 percent.

Because there was no mention of violence in the vignettes, the marked difference in the likelihood of violence attributed to the troubled person and the individuals described in the other four vignettes was most likely due to the reactions of the respondents to the clinical diagnostic aspects of the vignettes. It seems that the terms "alcohol abuse," "schizophrenia," and "cocaine abuse" are powerful negative stimuli to most survey participants. Link and colleagues (8) concluded that "public fears were out of proportion with reality." They continued: "While empirical studies show a modest elevation in violence among people with mental illnesses, the difference is never so dramatic as the differences in public response to the troubled person and the other vignettes. Moreover, empirical studies of violence uniformly show that only a minority of people with mental illnesses are violent."

Thus evidence indicates that a large proportion of the public devalues consumers by attributing to them a much higher potential for violence than is reasonable or than is supported by studies of violent behavior. Other studies (9,10,11) have demonstrated devaluation in other areas that reflect on the consumer's ability to function in society.

The aims of this study were to estimate caregivers' perceptions of the extent of society's devaluation of consumers and their families, to determine the constructs that are relevant to understanding devaluation, and to estimate the magnitude of the relationship between the devaluation of consumers and the devaluation of their families as measured by the Devaluation of Consumers scale and the Devaluation of Consumer Families scale (10).

We had three hypotheses. Our first hypothesis was that caregivers, because of the experiences they have acquired in caring for consumers in somewhat rejecting communities, would attribute to most people higher levels of devaluation than that found in representative samples of the U.S. population (12). Second, because schizophrenia is generally considered a more severe and more devastating psychiatric disorder than bipolar disorder, we hypothesized that caregivers who cared for consumers with schizophrenia would be more likely than caregivers who cared for consumers with bipolar disorder to believe that most people devalue consumers and their families. Third, we hypothesized that devaluation of consumers as measured by the Devaluation of Consumers scale would be strongly associated with the devaluation of families as measured by the Devaluation of Consumers' Families scale.

Methods

Samples

Caregivers who participated in two major studies of family burden and consumer outcome were compared on measures of devaluation. The two samples differed primarily in the diagnoses of the consumers for whom the study participants provided care. Sample A comprised 180 caregivers who provided care for consumers who lived primarily in New York City but also in suburbs north of the city (2). The predominant diagnoses of these consumers were schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders (137 consumers, or 76 percent); the remainder had diagnoses of major depression (23 consumers, or 13 percent) or bipolar disorder (20 consumers, or 11 percent). Of the 180 caregivers, 92 (51 percent) were the consumers' mothers. Forty-five (25 percent) of the caregivers were African American, 45 (25 percent) were Hispanic, and 90 (50 percent) were white.

The 281 caregivers in sample B provided care for consumers living in New York City and the suburbs north of New York City (1). The diagnoses of the 281 consumers whose caregivers were in sample B, based on the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, Lifetime Version (SADS-L) interview (13), were bipolar I disorder (152 consumers, or 54 percent), bipolar II disorder (28 consumers, or 10 percent), and schizoaffective disorder, manic type (101 consumers, or 36 percent). The mean±SD age of the 281 caregivers was 50±14.3 years. A total of 185 (66 percent) were women; 239 (85 percent) were white, 17 (6 percent) were African American, 22 (8 percent) were Hispanic, and 3 (1 percent) were Asian. A total of 152 consumers whose caregivers were in sample B (54 percent) and 68 consumers whose caregivers were in sample A (38 percent) lived with their caregivers.

Measures

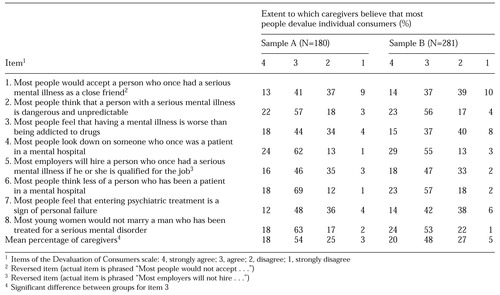

Devaluation of Consumers scale. The eight items of the Devaluation of Consumers scale, listed in Table 1, provide the basis for operationally defining the devaluation of consumers who have serious mental illness (10). Exploratory factor analysis of the responses of the 180 caregivers in sample A to the eight items yielded three related themes, or factors, in the content of the eight devaluation items. The percentage of total variance explained, after varimax rotation, was 28.7 for factor 1, 23.5 for factor 2, and 16.4 for factor 3.

Factor 1 is made up of the following five items: "looking down on" (item 4), "thinking less of" (item 6), describing persons with mental illness as "dangerous and unpredictable" (item 2), conceiving of psychiatric treatment as "a sign of personal failure" (item 7), and conceiving of mental illness as "worse than being addicted to drugs" (item 3). The content of these five statements focuses on the erosion of the consumer's status in society. All five statements describe consumers from a negative perspective, each in its own way placing the consumer in a lower status position. The five defining items of this factor indicate variation in status change and facilitate understanding of the relationships between reduction in status and other types of devaluation. We called this factor "status reduction."

The content of factor 2 conveys the pessimistic view that most employers would not hire a mental health consumer, regardless of whether he or she was qualified for the job (item 5), and that most women would not marry a man who had once been treated for a serious mental disorder (item 8). Although defined by only two statements, factor 2 identifies two important domains of life from which consumers are frequently excluded. The conception of consumers as poor risks for marriage or a steady job reduces their chances of participating in the roles of work, marriage, and the family. As a result, their roles in life are lessened, and their potential for achievement is constrained. We used the term "role restriction" to represent the theme of factor 2—the development of situations influenced by social values, employment policies, and discriminating attitudes that lead to the narrowing of opportunities for consumers and to their subsequent devaluation.

Factor 3, defined by item 1, is concerned with the belief that most people would not accept consumers as close friends. We called this factor "friendship refusal."

Although the three themes or factors are conceptually distinct and meaningful, the eight items were modestly to moderately correlated and, when treated as a unidimensional scale, had an internal consistency—or reliability—score of .82. For the 281 caregivers in sample B, the value of the reliability coefficient was also .82.

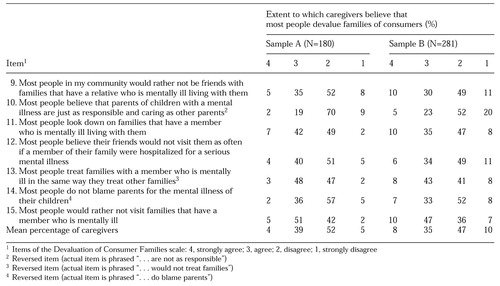

Devaluation of Consumer Families scale. The seven items of the Devaluation of Consumer Families scale, listed in Table 2, were developed to estimate the extent to which caregivers believe that most people devalue families that include one or more persons who have serious mental illness. Factor analysis of the responses of the caregivers in sample A to the seven items identified three related factors. The percentage of total variance explained, after varimax rotation, was 32.9 for factor 1, 20.9 for factor 2, and 17.2 for factor 3.

Factor 1, defined by items 9, 11, 12, and 15, places emphasis on looking down on families with mentally ill members—a status issue—and avoiding friendships and other forms of social contact with families that include a person with a mental illness. Because these negative statements are attributed to "most people," it seemed appropriate to label the behaviors described by the defining items of factor 1 as "community rejection."

Two related issues—treating families differently because a family member is mentally ill and blaming parents for the mental illnesses of their children—constitute factor 2, defined by items 13 and 14. The latter is a clear case of the attribution of cause, whereas the former is less specific and is more difficult to interpret, although it was moderately correlated with item 14. We assigned the label of "causal attribution" to factor 2 because of the dominance and specificity of item 14.

Factor 3, defined by item 10, is the perception that parents of children who have a mental illness are less responsible and caring than other parents. We called this factor "uncaring parents."

Although the relationships among the seven items also formed a distinct and meaningful three-dimensional structure, the dimensions were positively correlated. The result was a unidimensional scale with an internal consistency reliability coefficient of .71, indicating that 71 percent of the variability generated by the seven-item scale was reliable. The value of the reliability coefficient for sample B was .77; the relationship between the two scales was .58 for sample A and .62 for sample B.

A description of the procedures for scoring the Devaluation of Consumers scale and the Devaluation of Consumer Families scale can be obtained from the primary author.

Results

The extent to which caregivers believed that most people devalue consumers was measured by the percentage of caregivers who agreed or strongly agreed with "most people" statements that devalue consumers and disagreed or strongly disagreed with "most people" statements that reject devaluation. Table 1 presents the percentage of caregivers who endorsed each response category for each devaluation item. For example, 22 percent of the 180 caregivers of sample A strongly agreed and another 57 percent agreed with the statement "Most people think that a person with a serious mental illness is dangerous and unpredictable." Eighteen percent of the 180 caregivers disagreed and only 3 percent strongly disagreed that serious mental illness is perceived by the general public as an indication of dangerousness and unpredictability.

The profile of sample B was virtually identical to that of sample A, even though the consumers whose caregivers were in the two samples came from different diagnostic groups.

Having once been a patient in a mental hospital is a notable experience. It is a kind of unwelcome legacy that must be endured until it is somehow conquered. It is seldom forgotten, especially by potential landlords, employers, and friends. It is a stigma that lurks in the hearts, minds, and fears of many people. Caregivers understand the power and impact of this segment of the consumer's history. Eighty-four percent of the caregivers in sample B agreed or strongly agreed with item 4, "Most people look down on someone who once was a patient in a mental hospital." Only 1 percent of the caregivers in sample A strongly disagreed with this statement, and 13 percent disagreed. Caregivers in samples A and B, drawn from separate studies and caring for consumers with different diagnoses, had very similar profiles along the continuum from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree."

In the expression "think less of a person," as used in item 6, devaluation is clearly implied and seems to be closely associated with such descriptions as "less worthy" or "of less value." Items 4 and 6 indicate a judgmental reaction to consumers who have experienced hospitalization for mental illness, ascribing to them a lower status position. More directly, these responses are put-downs or expressions of rejection or criticism. An average of 83 percent of the caregivers agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, "Most people think less of a person who has been a patient in a mental hospital."

On average, 82 percent of the 461 caregivers in samples A and B agreed or strongly agreed with the content of items 2, 4, and 6. Of particular interest is the finding that 60 percent of the caregivers in sample A agreed or strongly agreed with item 7— "Most people feel that entering psychiatric treatment is a sign of personal failure." This result was replicated in sample B with a slightly lower—but not significantly—level of agreement. To associate psychiatric treatment with personal failure seems to be a drastic and unconsidered conclusion. However, the extreme perspectives embedded in the eight statements of Table 1, coupled with the extent to which caregivers agreed or strongly agreed with the statements about most peoples' perceptions of persons with mental illness and the results of studies of representative samples of the U.S. population, strongly suggest that we can expect disconcerting responses to these items.

As the bottom row of Table 1 indicates, about 70 percent of the 461 caregivers indicated agreement with the statements in the table, thus expressing a belief that most people would devalue consumers with serious mental illness. This percentage is higher than that for most individual items in the national surveys (7,8). For item 2—violence and unpredictability—79 percent of the caregivers either agreed or strongly agreed with the statements, whereas the corresponding percentages for national survey items were 61 percent and 60 percent (7). In another study (8), the proportion of responses that indicated a perceived tendency toward violence by persons with mental illnesses varied from 33 percent to 66 percent. Thus our first hypothesis was supported, although statistical significance could not be determined absolutely.

The differences between samples A and B on seven of the eight items, as well as on the total mean score, were not statistically significant on the basis of Student's t test. Thus the hypothesis that differences in the diagnoses of the consumers would have an effect on caregivers' beliefs was not supported.

If mental health care consumers are devalued by members of society, it seems likely that family members of these consumers will also be devalued. To test this hypothesis we correlated the Devaluation of Consumer Families scale with the Devaluation of Consumers scale for samples A and B. The product-moment correlation coefficients for the two scales were .58 (p<.001) and .62 (p<.001) for samples A and B, respectively, thus confirming hypothesis 3, that devaluation of consumers was correlated with devaluation of families.

The bottom row of Table 2 indicates that about 43 percent of the caregivers in both samples believed that most people devalue the families of consumers in the manner described by the seven items of the Devaluation of Consumer Families scale. Student's t tests were used to assess differences between the two samples in responses to each of the seven items as well as the difference between the two samples in total scale scores. The differences between samples A and B on each of the seven items and the difference between the total scale scores of the two samples were not statistically significant. Thus the specific diagnosis does not seem to affect the extent of the perceived devaluation of the families of consumers, just as in the case of individual consumers.

Conclusions

The dimensions of devaluation identified in the two limited sets of items we have described reveal some of the complexity of the devaluation domain and the need to explicate the dimensional structure of its content. The results of the two factor analyses described above identify clustered statements that suggest constructs that could serve as a basis for developing reliable and valid measures of devaluation. Constructs such as role, status, friendship ties, and community rejection already appear in the literature of the social and medical sciences and public mental health. By combining these constructs with the known and hypothetical effects of various types of devaluation, meaningful and useful measures of change, such as status reduction and role restriction, could be developed.

The use of other methods, procedures, and sources of information will contribute to the understanding of devaluation and its measurement. It is clearly important to know the size, content, and nature of the devaluation domain and the foundation of information and misinformation on which it is constructed. Focus group interviews of consumers and their families, mental health clinicians, caregivers, and researchers by well-trained and experienced interviewers will provide excellent information for discovering new ways of defining, expressing, and measuring the perception of devaluation.

Link and colleagues (10) and others have developed measures of devaluation and have published studies on relationships between devaluation and other constructs. An example is the study reported in this issue of Psychiatric Services, in which the relationships of devaluation and self-esteem were studied longitudinally with consumers as participants (14).

We conclude that the development of reliable and valid measures of devaluation will facilitate our ability to estimate and understand the impact of devaluation on the lives of consumers, their families, their caregivers, and those involved in the general welfare of consumers. In future work, it will be important to measure the relationships and the differences between devaluation as practiced by society and as perceived by various groups, such as consumers, caregivers, and mental health professionals. This information would provide one basis for designing programs for intervention in which consumers, their families, their caregivers, and those involved in the general welfare of consumers worked cooperatively to reduce the burden of devaluation.

Evidence for the devaluation of people who have serious mental illnesses can be found and comprehended in studies of representative samples of the U.S. population (7,8,9) and in more circumscribed studies of caregivers and consumers, as exemplified by this article. We believe that devaluation, when combined with the privatization of health care, results in a poor standard of treatment for many persons who have mental illnesses. However, some hope for improvement in the care and treatment of consumers can be found in programs that create environments in which the dignity and potential of consumers are recognized, respected, and developed. Such programs include multiple-family group therapy (15,16), pathways to housing (17), and many others (11).

It seems that the current prosperity of the United States offers a realistic fiscal basis for change and improvement in mental health services. However, public attitudes and beliefs and related behaviors that we have reviewed here also offer formidable impediments to change and progress. The important question remains: We have the resources, but do we have the will?

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants RO5-MH44690-04 and MH-51348 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Struening, Dr. Link, Mr. Hellman, and Dr. Herman are affiliated with the Mailman School of Public Health of Columbia University in New York City and with the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Dr. Perlick is with the Northeast Program Evaluation Center of the West Haven Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Connecticut and with the departments of psychiatry and epidemiology and public health of Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Dr. Sirey is with the department of psychiatry of New York Presbyterian Hospital, Westchester Division, and with Joan and Sanford I. Weill Medical College of Cornell University in White Plains, New York. Send correspondence to Dr. Struening at the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders Research Department, 100 Haven Avenue, Apartment 31D, New York, New York 10032 (e-mail, [email protected]). This paper is part of a special section on stigma as a barrier to recovery from mental illness.

|

Table 1. Distribution of caregivers' responses to eight statements that measure devaluation of consumers who have serious mental illness

|

Table 2. Distribution of caregivers' responses to seven statements that measure devaluation of families of consumers who have serious mental illness

1. Perlick D, Clarkin JF, Sirey J, et al: Burden experienced by caregivers of persons with bipolar affective disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 175:56-62, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Struening EL, Stueve A, Vine P, et al: Factors associated with grief and depressive symptoms in caregivers of people with serious mental illness. Research in Community and Mental Health 8:91-124, 1995Google Scholar

3. Lefley HP: Culture and chronic mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:277-286, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Lefley HP: Expressed emotion: conceptual, clinical, and social policy issues. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:591-598, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Solomon P, Draine J: Adaptive coping among family members of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:1156-1160, 1995Link, Google Scholar

6. Lefley HP, Hatfield AB: Helping parental caregivers and mental health consumers cope with parental aging and loss. Psychiatric Services 50:369-375, 1999Link, Google Scholar

7. Struening EL, Moore RE, Link BG, et al: Perceived Dangerousness of the Homeless Mentally Ill. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, Washington, DC, Nov 11, 1992Google Scholar

8. Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, et al: Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health 89:1328-1333, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Phelan J, Link BG, Moore RE, et al: The stigma of homelessness: the impact of the label "homeless" on attitudes toward poor persons. Social Psychology Quarterly 60:323-337, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening EL, et al: A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: an empirical assessment. American Sociological Review 54:400-423, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Neugeboren J: Transforming Madness: New Lives for People Living With Mental Illness. New York, William Morrow, 1999Google Scholar

12. Link BG, Schwartz S, Moore RE, et al: Public knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about homeless people: evidence for compassion fatigue. American Journal of Community Psychology 23:533-555, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research diagnostic criteria: rationale and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:773-782, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, et al: The consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 52:1621-1626, 2001Link, Google Scholar

15. McFarlane WR, Lukens E, Link BG, et al: Multiple-family groups and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:679-687, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Moltz DA: Bipolar disorder and the family: an integrative model. Family Process 32:409-423, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Tsembaris S, Eisenberg RF: Pathways to housing: supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 51:487-493, 2000Link, Google Scholar