Coping Resources of African-American and White Patients Hospitalized for Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

Forty-two African-American and 80 white patients hospitalized for bipolar disorder completed the Coping Resources Inventory. Total resource scores of the African Americans were significantly higher than scores of the whites, although differences in background variables between the two groups were not evident. The African-American group also scored significantly higher than the whites on the three scales indicating internal resources—cognitive, emotional, and spiritual-philosophical. No statistically significant differences were found for the two groups on the social and physical scales. Cultural orientations influencing personal life philosophies may explain the differences between the African-American and white patients on perceptions of their coping resources.

Understanding of the psychosocial aspects of bipolar disorder has advanced significantly in the past ten years through attention to issues that affect the disorder and treatment compliance (1) and stressors that may precipitate episodes (2). Several factors have been identified as psychosocial predictors of major affective recurrences, including inadequate social support, maladjustment in leisure and social activities, and inferior quality of relationships with extended family (3).

However, studies on perceived coping and major mental illness have focused primarily on patients' families (4,5) and on schizophrenia (6) rather than on patients with bipolar disorder. More information is needed on how patients of various ethnic and racial groups may differ in their perceptions of the coping resources available to them. Better understanding of these perceptions would be useful in developing culturally sensitive interventions that strengthen areas of psychosocial impairment and possibly decrease the likelihood of recurrence of affective instability.

The purpose of the study reported here was to compare the perceived coping resources of hospitalized African-American and white patients with bipolar disorder. To our knowledge, it is the first comparative study of its kind.

Methods

Participants

Participants took part in a larger study that compared two types of group therapy for inpatients with bipolar disorder. The data described in this report were collected at the first time point of that study, from February 1996 to March 1997. The participants, all between the ages of 18 and 65, were being treated for bipolar disorder in a university-managed, state- and county-funded psychiatric hospital. They were receiving medication, were aware of their diagnosis, and showed no mental retardation or organic impairment.

Selection of participants was based on their meeting the study criteria and expressing a willingness to participate.

The study instrument

The Coping Resources Inventory (CRI) is a 60-item self-report questionnaire that asks respondents to indicate how frequently they have engaged in the described behavior during the past six months (7). Scale scores are the sum of item responses for each of five scales; six items are reverse scored.

The cognitive scale measures the degree to which a person maintains a positive sense of self-worth, a positive outlook toward other people, and general optimism about life. The social scale measures the extent to which a person is involved in social networks that are capable of giving support during stressful times. The emotional scale measures the extent to which a person is able to express and accept a range of affect. The spiritual-philosophical scale measures the extent to which an individual's behaviors are guided by consistent values from personal philosophy or familial, religious, or cultural tradition. The physical scale measures the extent to which an individual engages in health-promoting behaviors thought to contribute to enhanced physical well-being.

The total resource score is obtained by summing the five scale scores. The higher the scale score, the greater the resource. Reliability and validity measures have been reported for the CRI (7): Cronbach's alpha ranged from .77 to .91 for the six dimensions and test-retest correlation coefficients from .60 to .73. Predictive, concurrent, and discriminant validity have been established. Although the scale had not previously been used with a population of individuals with bipolar disorder, results from a pilot test indicated that it was easily administered and provided useful information.

A 94-item form was used to collect demographic and diagnostic data from the participants' medical records. Religion was categorized by affiliation: Protestant, Catholic, Jewish, other, none, or not available. Social position was determined using Hollingshead's Two-Factor Index of Social Position (8). Primary financial support was categorized by source of support: self; the immediate support system, such as spouse, family, and friends; an agency or program, such as Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, Medicare, food stamps and welfare, Aid to Families With Dependent Children; or no visible means of support. Living arrangements after discharge were similarly categorized as whether the participant would be living alone; with immediate family; with a significant other, a friend, or extended family; or in a boarding home, structured living program, or halfway house.

Statistical analyses

The retrospective design used Student's t tests to examine the continuous data to determine whether statistically significant differences existed between the African-American and white participants for the total coping resources scores and the five scale scores. Chi square tests of independence were used to analyze the categorical variables to determine whether the two groups differed on background characteristics. The Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for the number of tests performed.

Results

A total of 122 patients—42 African-American and 80 white patients—completed the CRI. Participants were predominantly female (77 patients, or 63 percent), were admitted to the hospital voluntarily (72 patients, or 59 percent), were in the lower socioeconomic classes (100 patients, or 82 percent), and were without a partner (103 patients, or 84 percent). The mean±SD age was 35.4±9.5 years.

There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups for any of the demographic variables examined: gender, age, living arrangements when discharged, religious affiliation, employment before admission, social position, financial support, or marital status. There were also no significant differences between the two groups for any of the psychiatric variables examined: admission legal status, psychotic symptoms on admission, number of psychiatric hospitalizations, axis II diagnosis, or documented medication noncompliance before admission. Differences for three variables were significant when initial comparisons were made, but were not when adjustments were made for multiple tests: education (p=.018, adjusted p=.288), past or current involvement with the criminal justice system (p=.004; adjusted p=.064), and a secondary diagnosis of a substance use disorder (p=.016; adjusted p=.256). Cronbach's alphas for the CRI ranged from .76 to .92.

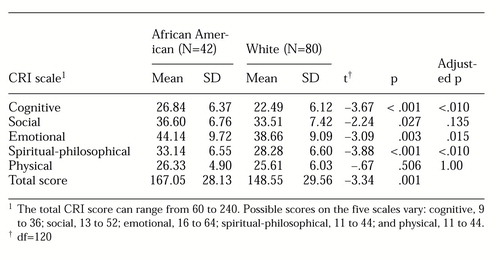

Total CRI scores of the African-American participants were significantly higher than those of the white participants (see Table 1). The African-American group also scored significantly higher than the white group on three of the five scales—cognitive, emotional, and spiritual-philosophical. No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups on the social and physical scales.

Discussion

The lack of statistically significant differences between the African-American and white patients on any of the background or psychiatric characteristics examined suggests that characteristics related to race account for the several significant differences between the two groups in their coping resources scores. These findings provide some support for those of Guarnaccia and Parra (5), although we sampled a different population. Those authors reported differential patterns based on ethnic group differences in their study of family members' experiences of caring for a mentally ill relative.

The African-American patients scored significantly higher than the whites on the total coping resource score and the three scales that indicate resources considered to be more internal than external, that is, factors embodied within the individual rather than accessed from others (9). This finding suggests that cultural orientations influencing personal life philosophies may explain the differences between the African Americans and the whites on perceptions of their coping resources.

Perhaps because of having overcome many obstacles in life in the past, the African Americans perceived themselves more as having an internal strength, a positive outlook, and more resources with which to cope than did the white participants. The strong spiritual foundation that is part of the upbringing of many African Americans (10) may instill powerful internal resources that persist into adulthood. Working with a sample of family members of patients with mental illness, Axelrod and colleagues (4) found that attitudes about self and a family's belief in its ability to care for a patient influenced the way family members thought about coping with the crisis of chronic mental illness.

We considered the question of whether the African Americans' significantly higher scores might have resulted from more frequent use of denial as a coping mechanism. We were unable to evaluate this possibility, but if denial was used more frequently by the African Americans, it was not pervasive enough to influence responses on all five scales. Differences in use of denial thus do not appear to account for the higher scores of the African-American patients.

Conclusions

Coping resources were perceived to be significantly higher by African-American than by white inpatients with bipolar disorder. The findings provide a foundation on which to base interventions that identify, support, and strengthen existing coping resources and to plan future studies with larger sample sizes.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant 1-R15-NR-03766-01A1 from the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health; by grant T15-SP-07775 from the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services faculty development program for 1995-1998; and by the Center for Nursing Research of the School of Nursing at the University of Texas-Houston Health Science Center.

Dr. Pollack is affiliated with the School of Nursing of the University of Texas-Houston (UT-H) Health Science Center, 1100 Holcombe Boulevard, Office 5.540, Houston, Texas 77030. Ms. Harvin is with the Prairie View A&M University College of Nursing in Houston; at the time of the study she was at the UT-H Harris County Psychiatric Center in Houston. Ms. Cramer is with the department of statistics at Rice University.

|

Table 1. Comparison of scores on the Coping Resources Inventory (CRI) of 122 hospitalized African-American and white patients with bipolar disorder

1. Hilty DM, Brady KT, Hales RE: A review of bipolar disorder among adults. Psychiatric Services 50:201-213, 1999Link, Google Scholar

2. Hammen C, Gitlin M: Stress reactivity in bipolar patients and its relation to prior history of disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:856-857, 1997Link, Google Scholar

3. Stefos G, Bauwens F, Staner L, et al: Psychosocial predictors of major affective recurrences in bipolar disorder: a 4-year longitudinal study of patients on prophylactic treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 93:420-426, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Axelrod J, Geismar L, Ross R: Families of chronically mentally ill patients: their structure, coping resources, and tolerance for deviant behavior. Health and Social Work 19:271-278, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Guarnaccia PJ, Parra P: Ethnicity, social status, and families' experiences of caring for a mentally ill family member. Community Mental Health Journal 32:243-260, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Mueser KT, Valentiner DP, Agresta J: Coping with negative symptoms of schizophrenia: patient and family perspectives. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:329-339, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Hammer AL: Manual for the Coping Resources Inventory: Research Edition. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1988Google Scholar

8. Miller, DC: Handbook of Research Design and Social Measurement, 5th ed. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1991Google Scholar

9. Rowe MA: The impact of internal and external resources on functional outcomes in chronic illness. Research in Nursing and Health 19:485-497, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Billingsley A: Climbing Jacob's Ladder: The Enduring Legacy of African American Families. New York, Touchstone Books, 1994Google Scholar