Establishing a Function-Based Mental Health Service Line in a VA Medical Center

Abstract

From 1994 through 1996, a general Veterans Affairs (VA) medical center reorganized its mental health services from a traditional discipline-based structure to a unitary service line organized around patient care functions. A comparison of data from 1993 and 1997 indicated increased efficiency, substantial transfer of patients from inpatient to outpatient care, and growth in academic programs not explainable solely by temporal, regional, or national trends or by trends within the VA medical center. Although the results should be interpreted conservatively because of the observational nature of the study, the reorganization appeared to facilitate the positive changes that occurred over the study period.

Clearly, it is important "to base development of new clinical services on sound principles … driven by well-constructed models" (1). However, few data exist for use in evaluating models for health service delivery.

Traditionally in Veterans Affairs (VA) medical centers, as in many other medical centers, mental health services have been divided among several professional disciplines, each headed by a chief. Clinical activity is coordinated through a committee of chiefs and a matrix organizational structure. This discipline-based "stovepipe" organization is prone to several problems. The reporting structure can be complex. Reorganization, redeployment, and coordination of services can be difficult when multiple lines of authority exist. Workload expectations can be inconsistent.

An alternative organization is the health service line or product line (2,3), defined as "a comprehensive set of services to meet the needs of a particular segment of the market … or an integrated set of services … distinguished from other services by the technology or specialty employed"(4). A key characteristic of a health service line is organization around integrated services or patient care functions. For example, all disciplines and staff involved in cardiology or in mental health are brought together in a single structure.

Most reports about service lines are qualitative (5,6,7). One recent semiquanitative study of vertical integration of services for patients with schizophrenia—not a service line by the strict definition—resulted in a decrease in average inpatient length of stay from 90 to 30 days and a 15 percent increase in outpatient appointments (8). However, the observational study reported here is, to our knowledge, the first quantitative study of the impact of establishing a hospitalwide mental health service line for all diagnoses.

Methods

An extensive description of the setting, process of change, and results is available from the first author. Briefly, the Providence VA Medical Center is a medium-sized general medical center located in an urban, working-class area and serving a veteran population of 180,000 in Rhode Island, eastern Connecticut, and southeastern Massachusetts. The medical center served 14,800 veterans in fiscal year 1993 and 15,700 veterans in fiscal year 1997, the first and last years of data analysis in the study.

In fiscal year 1994 the director of the medical center requested a budget-neutral reorganization of mental health services to emphasize efficiency and continuity of care. The process included input from administrators, service chiefs, and frontline clinical and clerical staff. The process can be summarized conceptually in terms of three aspects.

First, clinical and clerical staff involved in direct delivery of mental health care were consolidated into a single mental health and behavioral sciences service. The consolidation included staff from the disciplines of psychiatry and psychology and relevant staff from social work, nursing, and rehabilitation medicine who were involved in providing mental health care. The sole exception was that inpatient nursing staff remained with the nursing service, for reasons of coverage and specialized competencies.

Second, line reporting relationships were reorganized so that staff in each of the six existing patient care programs reported to a coordinator or medical director, rather than to their discipline chief. These six programs were the inpatient unit; the outpatient programs, which included the substance abuse clinic, the posttraumatic stress disorder clinic, and general clinics; the community care day program; and the residential homeless program.

All possible combinations of reporting relationships among psychology, nursing, and social work staff resulted. Physicians reported to the medical director of their program, but coordinators directed day-to-day activities of all staff including physicians. Coordinators and medical directors reported directly to the chief of the mental health and behavioral sciences service, producing flat organizational structure of six clinical programs, each organized around their respective patient care functions.

Third, all patient care processes were reorganized by a series of multidisciplinary process action teams. For example, all new patients were funneled through a single assessment clinic to assign patients to specific programs on the basis of diagnosis, workload equity, and academic need. The reorganization was complete by the end of fiscal year 1996.

Data from before, during, and after the reorganization were derived from the administrative database. Quantitative variables were chosen on the basis of the medical center director's goals of maximizing "continuity, effectiveness, and efficiency of mental health care," echoing key parameters articulated by the VA undersecretary for health (3).

Results

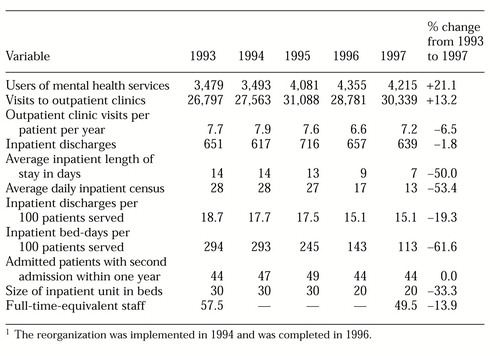

Table 1 summarizes changes in key service variables from 1993 to 1997. Over this period, the number of veterans served by the medical center increased by 21.1 percent, and use of inpatient services was reduced by 61.6 percent. Increased efficiency was evidenced by a concomitant decrease in mental health staff of 13.9 percent—.9 full-time equivalents (FTEs) for physicians; two FTEs for doctoral-level psychologists; one FTE each for master's-level social workers, registered nurses, and physicians assistants; and 2.1 FTEs for clerical staff. Staff reduction was achieved through attrition and consolidation of outpatient positions. No inpatient or outpatient clinical program was closed.

Without a formal controlled trial, the changes summarized in Table 1 cannot definitively be attributed to the establishment of the mental health service line rather than to other concurrent factors. Accordingly, we investigated several other potential contributing forces. First, it is not likely that the changes seen at this VA medical center were passively driven by temporal trends, although during the years of the study there were some clear trends away from inpatient care and toward outpatient care. For example, across VA medical centers nationwide, length of stay for mental health treatment decreased 11 percent (9), compared with 50 percent at our medical center. Inpatient mental health beds per 10,000 veterans decreased 31.2 percent nationwide, compared with 33 percent at our center. The percentage of resources dedicated to inpatient mental health care at VA centers nationwide as a percentage of total mental health resources decreased 11.2 percent. Finally, the number of veterans served by the VA New England regional network increased by 3.5 percent, compared with 21.1 percent at our mental health center.

Second, it is not likely that the patients seen after the reorganization were less severely ill, because several clinical severity indexes did not change on a regional network level (data available on request). Third, reductions nationwide in VA inpatient bed-days of 34 to 43 percent have been reported for major medical and psychiatric diagnoses between fiscal years 1992 and 1996 (10), compared with a 61.6 percent reduction at our mental health center. Fourth, no concurrent reorganizations were implemented at our medical center, and no other changes occurred that could explain these data. However, bed-days for medical-surgical care decreased by 41 percent over this interval.

Concern has sometimes been expressed that the formation of service lines can erode the academic mission of a health care organization by consolidating traditionally distinct professional disciplines. In fact, the number of psychology doctoral trainees remained stable at three FTEs, and psychiatry residents increased from nine to 10.5 FTEs, a 16.7 percent increase. Between 1993 and 1997, annual research funding for investigator-initiated grants to mental health clinical staff from federal agencies increased from $140,040 to $184,188, a 31.5 percent increase; in 1998 funds rose to $308,350, an increase of 120 percent over 1993 funding.

Discussion

The limitations in this observational study are clear. First, quality of care was not directly assessed, and thus we cannot exclude the possibility that patients deteriorated clinically during this time. Second, sicker patients may have dropped out of treatment. However, the comparative national and regional data presented above reduce the likelihood of these possibilities to some degree. Third, it is possible that the changes were due in part to the idiosyncratic features of the personnel or hospital. Such site-specific factors likely do play a role, and we suggest that the reorganization played a facilitative rather than a causative role in the effects seen.

Several mechanisms may be involved, principally reorganizing work units around patient care functions and especially realigning reporting structures to support this reorganization. We suggest that these changes facilitated development of a function-based culture that in turn stimulated and supported reworking of patient care processes.

Clearly, controlled investigations are needed, especially those including direct measurement of quality of care and patient outcome. The findings of this study suggest some of the key components and mechanisms to consider in reorganizing and evaluating the delivery of mental health services.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Martin Charns, Ph.D., for helpful comments on an early draft of this report. This report was partly supported by VA Health Services Research and Development grant DEV97-015.

The authors are affiliated with the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center (116A), Providence, Rhode Island 02908-4799 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Bauer is also affiliated with the department of psychiatry and human behavior at Brown University in Providence. Dr. Chirico-Post is with the office of the dean at Brown University.

|

Table 1. Changes in service-related variables between 1993 and 1997 at a Veterans Affairs medical center that established a unified mental health service line1

1 The reorganization was implemented in 1994 and was completed in 1996

1. Kiser L, King R, Lefkovitz P: A comparison of practice patterns and a model continuum of ambulatory behavioral health services. Psychiatric Services 50:605-606,618, 1999Link, Google Scholar

2. Charns M, Tewksbury C: Collaborative Management in Health Care: Implementing the Integrative Organization. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1993Google Scholar

3. Kizer K: Prescription for Change: The Guiding Principles and Strategic Objectives Underlying the Transformation of the Veterans Healthcare System. Washington, DC, Veterans Health Administration Headquarters, 1996Google Scholar

4. Charns M: If you are confused about the definition of service line management, you are not alone. Transition Watch (VA Management Decision Resource Center, Health Services Research and Development Service, Boston) Fall, 1997, pp 1-3Google Scholar

5. Campbell V: Product line management defined. Topics in Health Records Management 10:1-8, 1990Medline, Google Scholar

6. Janssen R, van Merode F: Hospital management by product line. Health Services Report 4:25-31, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

7. O'Malley J, Cummings S, Serpico D: Pragmatic strategies for product-line management. Nursing Administration Quarterly 15:9-15, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Smith T, Hull J, Hedayat-Harris A, et al: Development of a vertically integrated program of services for persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 50:931-935, 1999Link, Google Scholar

9. Rosenheck R, DiLella D: Department of Veterans Affairs National Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System, FY95-FY97 Reports. West Haven, Conn, VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 1996-1998Google Scholar

10. Ashton C, Petersen N, Sourchek J, et al: A Cohort-Based Analysis of Utilization and Survival Rates Across the VA Health Care System. Washington, DC, VA Health Services Research and Development Service, 1997Google Scholar