Service Use by Elderly Patients After Psychiatric Hospitalization

Abstract

The extent and source of services used by older adults discharged to a community setting after a psychiatric hospitalization were examined in a prospective follow-up study. Patients were asked about service use in structured telephone interviews one month after hospital discharge. Subjects had comorbid medical conditions and high levels of functional impairment. Service use was low, highly skewed, and spread across three sectors of care—mental health specialty care (38 percent of the services), general medical care (35 percent), and social services and formal aging services (27 percent). Most service episodes were related to mental disorder.

The cost and rising incidence of geropsychiatric hospital treatment is a major concern (1,2,3,4,5). Yet as inpatient stays for elderly persons on psychiatric units have shortened and older adults are discharged with increased dependency, the availability and sufficiency of posthospital services becomes a pressing issue. Elderly patients return to community care after psychiatric hospitalization with multiple needs, including those stemming from mental disorder, comorbid medical conditions, and problems with daily functioning. Discharge from acute hospitalization is a critical transition for elderly patients, and inadequate postdischarge service may undermine the effectiveness of inpatient care (6). However, virtually no studies have followed older psychiatric patients into community care to examine their service utilization.

The underutilization of specialty mental health services among elderly persons is well documented (7). The general health sector has served as their de facto mental health system (8). The functional limitations experienced by many elderly persons suggest the need for social services and formal aging services. However, the few available studies of this issue suggest that elderly persons with mental disorders underutilize social services (9).

The objectives of the study reported here were to identify the extent of formal service utilization by older adults discharged home after acute psychiatric care and to identify the types and sectors of care used.

The study uses a conceptualization of care in three sectors: specialty mental health service, general health service, and social and formal aging services. Consistent with the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study (8), specialty mental health service is defined as care provided by psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric social workers, counselors, or mental health specialists. General health service is defined as care provided by nonpsychiatric physicians, nurses, medical social workers, physical therapists, occupational therapists, recreational therapists, nurse aides, and pharmacists. Social services and formal aging services are defined as care provided by nonpsychiatric gerontological social workers, social agency staff, personal care aides, and agency-sanctioned volunteers.

Methods

The sample was made up of 60 older adults discharged from the geropsychiatric unit of a large urban teaching hospital to a community setting such as their own home, another person's home, a supported living facility, or other non-nursing-home setting. The participants in the study were recruited from October 1994 through January 1995. Ninety-two percent of those approached to participate in the study consented. For patients with cognitive impairment, consent was also obtained from a collateral, the family member designated by the hospital social worker as the person most involved with the patient. Data were collected during hospitalization and through a structured telephone interview with patients or collaterals one month after the patient's discharge.

Data on patients' age, race, marital status, and insurance status were abstracted from medical records. Medical records were also the source of information on patients' DSM-III-R axis I psychiatric diagnosis and comorbid axis III medical conditions. Patients' physical functioning was assessed during the one-month follow-up interview using questions about the 13 activities of daily living from the Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire of the Older Americans Research and Service Center (10).

In the postdischarge telephone interview, we asked study participants if during the month since discharge they had seen a particular provider, such as a psychiatrist, other physician, or psychiatric in-home nurse, or if they had used a particular type of service, such as a doctor's visit for a medical condition, day care, or outpatient electroconvulsive therapy. Study participants were read a list of types of providers and services and asked if they had used each one. They were also asked if they used a given service for help with a mental health problem, a medical condition, or limitations in physical functioning or activities of daily living.

Patients' responses reflected the number of service episodes but not the intensity or number of hours of service received. The research team assigned the types of providers and services mentioned by the patients to one of the three sectors of specialty mental health, general health, or social and aging services.

Results

Like the elderly population in general, 75 percent of the sample were female, and half were widowed. African Americans, who made up 20 percent of the sample, and Medicaid recipients, 12 percent of the sample, were overrepresented due to the demographic characteristics of the population served by the study hospital.

Before being hospitalized, 37 percent of the study patients lived alone, and 28 percent did so after discharge. Seventy-six percent of the patients had a diagnosis of an affective disorder, 8 percent had dementia, 8 percent had psychotic disorders, and 8 percent had other disorders such as adjustment disorder and alcohol-related disorders. The mean± SD number of comorbid medical conditions was 3.1±1.9, with a range from none to eight. The mean level of functional dependence was 4.9± 3.6 on a possible scale from 0, total independence, to 12, total dependence. Only 13 percent of the study participants were fully functional one month after discharge.

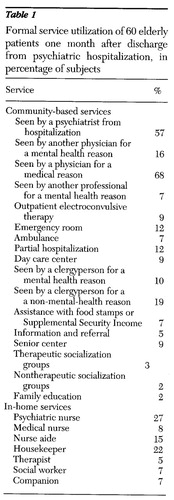

Table 1 shows the types of services received by study participants. Postdischarge service use was low and highly skewed, with a small minority of patients using a large number of services. The median number of services used was one, the mode was two, and the mean was 4.2.

Mental disorder was the reason for 44 percent of the service episodes, physical health conditions for 32 percent, and functional impairment for 23 percent of services.

Thirty-eight percent of the services received by the study participants were from the mental health specialty sector, 35 percent were from the general health sector, and 27 percent were from the social and aging services sector. The median numbers of service contacts with the mental health sector, the general health sector, and the social and aging services sector were very low—one, one, and none, respectively. Wide variance in use elevated the mean numbers of contacts, which were 4.2±5.3 for the mental health sector, 3.6±7 for the general health sector, and 4±7 for the social and aging services sector. Two-thirds of the patients used two or three of the three sectors of care.

Discussion and conclusions

The study participants' high levels of medical comorbidity and functional impairment suggest that despite gains made during psychiatric hospitalization, elderly patients return to the community needing substantial care. Although mental disorder was the reason for most service use, the general medical sector played a large role in the study participants' posthospital care. The percentage of services received from the specialty mental health sector (38 percent) was lower than the percentage of services received because of a mental disorder (44 percent). Moreover, while 32 percent of services were related to medical need, 35 percent of services received by participants were from a medical provider. These findings reflect elderly patients' reliance on providers in the general medical sector for mental health care, even among those with a severe mental disorder.

Although most study participants had at least one service contact during the one-month study period, the skewed distribution of service use indicates that a few individuals consumed a disproportionate amount of services. This finding raises concerns about whether elderly patients discharged from psychiatric hospitalization receive enough services. The period of transition from acute hospital care to community care should be a time of intense service use. Patients who have just been discharged have the potential to be well connected with service systems because hospital staff can arrange home health care, follow-up care, and services for functional dependency. Patients who have required hospitalization for a mental disorder are probably among the most severely ill patients and therefore have the most critical needs.

Given shorter psychiatric hospital stays, optimizing community care is of increasing importance. Outcomes achieved from expensive inpatient treatment may be undermined by inadequate postdischarge service. Future studies should identify factors that enhance and impede service use of elderly patients discharged from psychiatric hospitalization. The findings of this study showing elderly patients' need for services from multiple sources of care highlight the importance of coordination of care for individual patients.

Dr. Proctor is Frank J. Bruno professor of social work research and director of the Center for Mental Health Services Research in the George Warren Brown School of Social Work at Washington University, 1 Brookings Drive, St. Louis, Missouri 63130 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Morrow-Howell is associate professor and Mr. Ringenberg is a doctoral student in the School of Social Work. Dr. Rubin is professor of psychiatry at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

|

Table 1. Formal service utilization of 60 elderly patients one month after discharge from psychiatric hospitalization, in percentage of subjects

1. Atay JE, Witkin MJ, Manderscheid RW: Data Highlights of Utilization of Mental Health Organizations by Elderly Persons. DHHS Pub SMA 95-3032. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1995Google Scholar

2. Goldsmith HF, Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ, et al: Projections of inpatient admissions to specialty mental health organizations:1990 to 2010. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:478-483, 1993Google Scholar

3. Lyons JS, Pressman P, Pavkov T, et al: Psychiatric hospitalization of older adults: comparison of a specialty geropsychiatric unit to general psychiatric units. Clinical Gerontologist 12(2):3-17, 1992Google Scholar

4. Redick R, Taube CA: Demography and mental health care of the aged, in Handbook of Mental Health and Aging. Edited by Birren JE, Sloane RB. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1980Google Scholar

5. Essock SM: The influence of medical comorbidities and other patient characteristics on resource consumption on psychiatric wards. Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research 8:133-142, 1987Medline, Google Scholar

6. Morrow-Howell N, Proctor EK, Mul AC: Adequacy of discharge plans for elderly patients. Social Work Research and Abstracts 27:6-13, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Burns BJ, Taube CA: Mental health services in general medical care and nursing homes, in Protecting Minds at Risk. Edited by Fogel B, Furino A, Gottlieb G. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

8. Regier DA, Goldberg ID, Taube CA: The de facto US mental health services system: a public health perspective. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:685-693, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Slivinske L, Fitch V, Mosca J: Predicting health and social service utilization of older adults. Journal of Science and Research 20(1-2):21-40, 1994Google Scholar

10. Multidimensional Functional Assessment: The OARS Methodology: A Manual. Durham, NC, Duke University Medical Center, Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, 1978Google Scholar