Measuring Client Satisfaction With Assertive Community Treatment

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: A mailed survey was used to measure satisfaction of seriously mentally ill clients with services provided by an assertive community treatment team. METHODS: A detailed 35-item questionnaire was mailed in 1995 to all 174 clients of the Brockville (Ontario) Psychiatric Hospital's assertive community rehabilitation program. RESULTS: The rate of return was 51 percent. Compared with clients who did not return the survey, the respondent group had significantly fewer males and fewer clients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia; respondents had been associated with the program for less time. Factor analysis of the survey responses revealed three principal components accounting for 46 percent of the total variance in responses. The factors were interpersonal aspects of care, client involvement in treatment, and medication and treatment issues. Respondents were generally satisfied with service from the program, but they were dissatisfied with side effects of medication and the amount of medication they were taking. CONCLUSIONS: A mailed survey appears to be an efficient and nonintrusive way to collect satisfaction data anonymously from persons with serious mental illness who are clients of an assertive community treatment team. The results highlight areas of need that the team can address.

Assertive community treatment for persons with serious mental illness has developed over the past 25 years (1,2,3). This model for service delivery has been shown to be successful in many parts of the world, and in some jurisdictions it has largely replaced institutional care (4,5). Some of the early empirical studies of assertive community treatment included interviews with clients to assess their satisfaction with services (3), but very few subsequent reports have included data on satisfaction.

Most reports of client satisfaction with assertive community treatment have not used recognized instruments to measure satisfaction (3,6,7). Other studies (8,9,10,11,12) have used ad hoc surveys or the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (13), which provide only general measures of satisfaction and may not capture areas of dissatisfaction (14). Ruggeri (15) also found domain-specific measures to be more sensitive to dissatisfaction than general questions. Moreover, from the perspective of program evaluation, general satisfaction questionnaires are considered to yield overly positive results that might contribute to efforts to "whitewash" a particular program or service (16).

Because the assertive community treatment model increasingly represents a standard for treating persons with serious mental illness, soliciting clients' opinions about the services this model provides is critical. Consistent with increasing accountability to consumers, efforts to obtain input from clients that is both meaningful and reliable are equally essential.

This report describes our attempt to use a mailed survey to evaluate satisfaction with assertive community treatment services provided to a seriously mentally ill population. The goal was to obtain information from clients that would be useful for optimizing services provided by the program.

Methods

Subjects

In 1995, when the survey was conducted, 174 clients were affiliated with the Brockville Psychiatric Hospital's assertive community rehabilitation program. Clients in the program are heavy users of psychiatric services (17), with long histories of psychiatric care. At the time of the survey 90 men and 84 women were participating in the program. They ranged in age from 19 to 74 years, with a median age of 42 years. Of the 174 clients 108 (62 percent) were single, 17 (10 percent) were married, 44 (25 percent) were separated or divorced, and the remainder (five clients, or 3 percent) were widowed.

Of the 174 clients, 103 (59 percent) did not finish high school, 59 (34 percent) had high school diplomas, and 12 (7 percent) had undergraduate degrees. Psychiatric diagnoses included schizophrenia (101 clients, or 58 percent), affective disorders (37 clients, or 21 percent), personality disorders (11 clients, or 6 percent), substance abuse disorders (six clients, or 3 percent), other psychotic disorders (three clients, or 2 percent), and nonpsychotic disorders (16 clients, or 9 percent). Clients lived in community settings, except for brief periods of hospitalization.

Services provided

The assertive community rehabilitation program was established in 1990 to serve heavy users of psychiatric care in eastern Ontario. The program is based on the principles of assertive community treatment (2,18). Two teams provide services, and each team includes a psychiatrist, nurses, social workers, a vocational counselor, and a recreation counselor. Although each client has a primary worker, all team members provide services to clients. The staff-to-client ratio is approximately one to ten. Staff are available seven days a week, 24 hours a day, through an after-hours call system. Individualized treatment plans are developed based on functional assessments. Frequency of client contacts ranges from several times daily to once a week, and contacts occur in shopping malls, restaurants, and clients' homes and places of work.

In addition to addressing clinical symptoms, the teams support clients in activities of daily living such as shopping, housing, personal hygiene, cooking, budgeting, and transportation. Team members help clients use their time constructively in leisure, vocational, and social pursuits. Families and community agencies with which clients are involved receive active team support. Funds are available to help the team prevent unnecessary admissions to the hospital. For example, funds are used for emergency housing, groceries, and clothing. The program has been described previously (19).

The program manager and team psychiatrist completed the Fidelity Measure for Assertive Community Treatment (20), which showed that the program adheres very closely to the model originally proposed by Stein and Test (2). Out of a possible score of 14, the program received a score of 13.6.

Survey instrument

An instrument developed by Hansson (21) to assess satisfaction with outpatient psychiatric care in Sweden was chosen for this project as it addresses a wide range of relevant service issues. The questionnaire has the advantage of being suitable for use as a mailed survey in contrast to other instruments designed for use in interview formats (22,23). The questionnaire was translated into English and modified to reflect aspects of the assertive community treatment program.

The modified Hansson survey has 35 questions covering the location of services, services clients expect, delays in obtaining services, clients' input into treatment, information received about drug treatment, satisfaction with treatment, access to clinical files, satisfaction with the therapist, family involvement in treatment, the treatment process, and overall satisfaction. Members of the team were consulted about the wording of the survey items. Possible responses to most items ranged from 1, most negative, to 7, most positive. A rating of 0 on certain items enabled the respondent to indicate that the question was not relevant to his or her situation.

Six items included at the end of the survey, also on a 7-point scale, formed a general satisfaction questionnaire adapted from the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (13).

Procedure

In May 1995 the survey was mailed to each of the 174 clients in the program. A covering letter from the first author, who is not a member of the team, explained the purpose of the survey and that responses were anonymous and confidential. A postage-paid return envelope was included with each survey. If a client did not respond to the survey after one month, a second package was sent to the client, as suggested by Hansson (21).

Team members were informed when the survey was sent to clients. Team members were instructed to discuss the survey with clients only if clients asked about it.

Results

Completed questionnaires were returned by 88 clients, for a 51 percent response rate. No differences were found in age or the lifetime number of days hospitalized between clients who returned the survey and those who did not. Compared with nonresponders, the respondent group had smaller proportions of males (χ2= 3.91, df=1, p<.05) and of persons with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (χ2=3.91, df=1, p<.05). The respondents had been associated with the program for a shorter time than those who did not return the survey (t=2.38, df=170, p<.05).

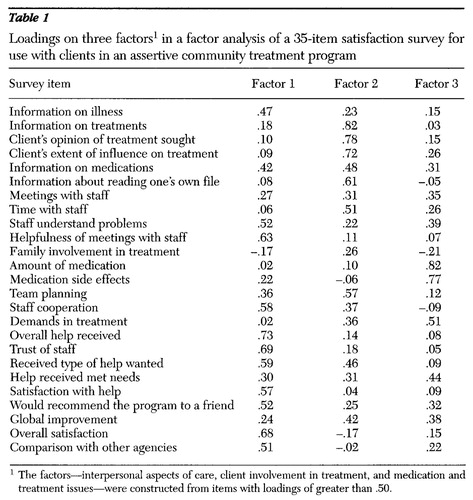

Responses to the questionnaire were factor analyzed. A univariate principal components solution indicated a relatively weak general factor—that is, the factor involved virtually all items—and a series of bipolar factors that were difficult to interpret. A varimax rotation was used, which is a method of model transformation that seeks a simple factor structure consisting of group factors and tends to eliminate bipolar factors of the first three principal components. The rotation produced three group factors accounting for 46 percent of the total variance in client satisfaction.

Based on item loadings above .50, shown in Table 1, the three group factors were identified as interpersonal aspects of care (18 percent of variance), client involvement in treatment (17 percent of variance), and medication and treatment issues (11 percent of variance). Reliability analysis of the three factors produced alphas of .86, .79, and .70, respectively. Oblique rotation did not change the structure significantly. Thus the varimax solution appeared to furnish the most parsimonious and useful structure for describing variation in client satisfaction.

No significant correlations were found between satisfaction and age, previous hospitalization, and length of time in the program. T tests for independent samples revealed no gender differences in satisfaction on any of the three factors. A one-way analysis of variance indicated differences between diagnostic groups on the medication and treatment issues factor, but they did not achieve statistical significance (p=.055).

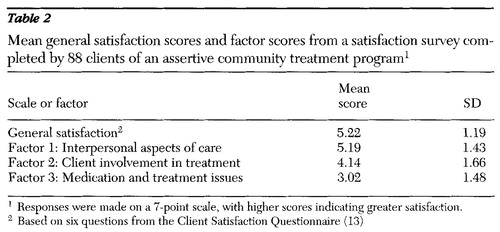

As Table 2 shows, responses to the six questions from the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire measuring general satisfaction indicated that respondents were moderately satisfied with services provided by the program. Table 2 also presents means and standard deviations for the three factors.

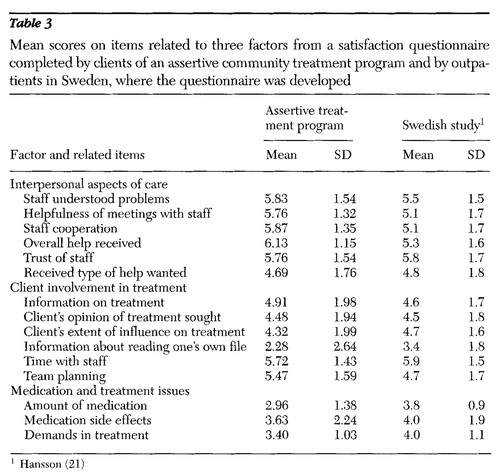

Mean ratings for individual items contributing to the three factors are shown in Table 3, along with the scores for psychiatry outpatients attending a hospital clinic in Sweden where the original questionnaire was used (21). In general, the scores from both studies are similar.

Although the six overall satisfaction questions yielded generally favorable results, inspection of responses to more specific survey questions revealed areas in which clients were dissatisfied. Most notably, our results support previous findings among inpatients that indicate less satisfaction on items related to information and influence over treatment (24). In several areas, more than 10 percent of respondents to our survey were dissatisfied. The areas included medication side effects (38 percent), amount of medication (36 percent), demands in treatment (31 percent), the extent of clients' influence over treatment (30 percent), whether their opinion was considered in planning treatment (23 percent), receipt of information about treatment options (20 percent), receipt of information about reading their own file (18 percent), type of help received (17 percent), and amount of help received (12 percent).

Most clients had favorable opinions of the services they received from the program teams. Results showed that the majority of respondents felt that they spent enough time with their primary worker (81 percent), that their worker understood their problems (86 percent), and that conversations with their worker were helpful (86 percent). Most respondents felt satisfied with treatment planning (75 percent), cooperation among staff (86 percent), and the overall help they received (88 percent), and most felt they could trust the team workers (78 percent). The majority of respondents also felt their needs were met by the team (86 percent), were satisfied with the overall service (80 percent), and felt they received more help from the program than from other agencies (69 percent).

Discussion

Client satisfaction surveys have been conducted with clients of assertive community treatment programs in the past, but have either used the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (13), which is based on general measures, or ad hoc questionnaires devised as parts of larger studies. Previous satisfaction surveys have not provided detailed information about clients' views of services.

The mailed survey appears to be an efficient and nonintrusive way to collect satisfaction data anonymously from seriously ill clients of assertive community treatment teams, as well as from more traditional psychiatry outpatients attending a hospital clinic (21). Rates of return of the mail survey were similar to those reported previously (21,25). Reviews by Lebow (26,27) indicated that the average rate of completion of mailed questionnaires is between 38 percent and 46 percent, suggesting that our 51 percent return rate is better than average. Our results suggest that clients with significant psychiatric impairments are capable of responding to a mailed survey.

Analysis of the characteristics of those who returned the survey and those who did not revealed some differences, including a smaller proportion of males in the respondent group and a smaller proportion of respondents with a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Also, respondents had a shorter affiliation with the program. Although additional variables, such as personality and acquiescence (24), were not explored, the findings indicate that the group who responded to the survey may have been a representative sample of the clients served.

The modified version of Hansson's questionnaire (21) has provided our program's teams with satisfaction data about several aspects of their operation. Although the program focuses on meeting basic needs, clients appeared primarily to value interpersonal factors. For example, many clients would have liked to spend more time with their worker. This finding supports the idea that the worker-client connection is as important in assertive treatment as it is in other, more traditional interventions, such as casework models (7) and crisis intervention (28).

Our findings support other satisfaction surveys of clients of assertive community treatment programs in randomized studies. General satisfaction as measured using the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (13) has been found to be moderately high in several studies (10,11,12,19). Some comparisons have found satisfaction to be higher among clients in assertive community treatment than among those in control groups (8,9,12).

Although all the clients in our program were surveyed, the results may be limited because 49 percent of clients did not respond, and fewer male than female clients returned the survey. It is also possible that only the more satisfied and higher-functioning clients completed the questionnaire. Nevertheless, demographic characteristics of those who did and did not respond were comparable. Perhaps more important, respondents identified areas of dissatisfaction as well as satisfaction with the program's services, which suggests that results of this survey can be considered in a meaningful way.

In particular, the survey has highlighted specific client needs to members of the treatment teams. Some needs have already been addressed. For example, clients of one team are now given a written summary of their treatment plan and asked to sign a statement specifying their participation in the development of that treatment plan. The team is also revising its medication policy to reinforce information given to clients about benefits and side effects of medications. This approach includes printed cards listing the medications that each client receives, the purpose and dosage of each drug, and adverse effects that need to be monitored, as well as pamphlets that remain in the client's home. The team has also discussed forming a consumer advisory board to provide an avenue for clients to have direct input into the operation of the team.

Conclusions

Our study found that use of the modified Hansson survey instrument is feasible in a mailed survey and that it is capable of providing meaningful information to assertive community treatment teams. Future studies of satisfaction among clients of assertive community teams might focus on examining additional aspects of service that are unique to these programs. Other areas that need to be explored are clients' views about receiving services in their residence instead of at a clinic, receiving services from multiple team members rather than a single clinician, and receiving comprehensive care instead of specialized care from several sources.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ronald L. Cohen, Ph.D., for translating the Hansson questionnaire; J. Stuart Lawson, Ph.D., for assistance with data analysis; and Andrea Catellier for coordinating the survey.

Dr. Gerber is director of research and Ms. Prince is research coordinator at Brockville Psychiatric Hospital, P.O. Box 1050, Brockville, Ontario, Canada K6V 5W7 (e-mail, [email protected] [Attn: Gary Gerber]). Dr. Gerber is also clinical assistant professor in the departments of psychiatry and psychology at the University of Ottawa, and Ms. Prince is a doctoral candidate at Carleton University in Ottawa.

|

Table 1. Loadings on three factors1 in a factor analysis of a 35-item satisfaction survey for use with clients in an assertive community treatment program

1 The factors—interpersonal aspects of care, client involvement in treatment, and medication and treatment issues—were constructed from items with loadings of greater than .50.

|

Table 2. Mean general satisfaction scores and factor scores from a satisfaction survey completed by 88 clients of an assertive community treatment program1

1 Responses were made on a 7-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

2 Based on six questions from the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (13)

|

Table 3. Mean scores on items related to three factors from a satisfaction questionnaire completed by clients of an assertive community treatment program and by outpatients in Sweden, where the questionnaire was developed

1 Hansson (21)

1. Marx AJ, Test MA, Stein LI: Extrohospital management of severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 29:505-511, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to mental hospital treatment, I: conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392-397, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hoult JR, Reynolds I, Charbonneau-Powis M, et al: Psychiatric hospital treatment versus community treatment: the results of a randomised trial. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 17:160-167, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Burns BJ, Santos AB: Assertive community treatment: an update of randomized trials. Psychiatric Services 46:669-675, 1995Link, Google Scholar

5. Drake RE: Brief history, current status, and future place of assertive community treatment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:172-175, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Wright RG, Heiman JR, Shupe J, et al: Defining and measuring stabilization of patients during four years of intensive community support. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:1293-1298, 1989Link, Google Scholar

7. Solomon P, Draine J: Satisfaction with mental health treatment in a randomized trial of consumer case management. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:179-184, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bond GR, Witheridge TF, Dincin J, et al: Assertive community treatment for frequent users of psychiatric hospitals in a large city: a controlled study. American Journal of Community Psychology 18:865-891, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Muijen M, Marks I, Connolly J, et al: Home based care and standard hospital care for patients with severe mental illness: a randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal 304:749-754, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Marks IM, Connolly J, Muijen M, et al: Home-based versus hospital care for people with serious mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 165:179-194, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Audini B, Marks IM, Lawrence RE, et al: Home-based versus out-patient/in-patient care for people with serious mental illness: phase II of a controlled study. British Journal of Psychiatry 165:204-210, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Wolff N, Helminiak TW, Morse GA, et al: Cost-effectiveness evaluation of three approaches to case management for homeless mentally ill clients. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:341-348, 1997Link, Google Scholar

13. Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al: Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning 2:197-207, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Lovell K: User satisfaction with in-patient mental health services. Journal of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing 2:143-150, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Ruggeri M: Patients' and relatives' satisfaction with psychiatric services: the state of the art and its measurement. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 29:212-227, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Rutman L, Mowbry G: Understanding Program Evaluation. London, Sage, 1983Google Scholar

17. Surles RC, McGurrin MC: Increased use of psychiatric emergency services by young chronic mentally ill patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:401-405, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Olfson M: Assertive community treatment: an evaluation of the experimental evidence. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:634-641, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

19. Lafave HG, de Souza H, Gerber GJ: Assertive community treatment of severe mental illness: a Canadian experience. Psychiatric Services 47:757-759, 1996Link, Google Scholar

20. McGrew JH, Bond GR, Dietzen L, et al: Measuring the fidelity of implementation of a mental health program model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62:670-678, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Hansson L: The quality of outpatient psychiatric care: a survey of patient satisfaction in a sectorized care organization. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science 3:71-81, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Tanner B: A multidimensional client satisfaction instrument. Evaluation and Program Planning 5:161-167, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Perreault M, Leichner P, Sabourin S, et al: Patient satisfaction with outpatient psychiatric services: qualitative and quantitative assessments. Evaluation and Program Planning 16:109-118, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Svensson B, Hansson L: Patient satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric care: the influence of personality traits, diagnosis, and perceived coercion. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 90:379-384, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Kelstrup A, Lund K, Lauritsen B, et al: Satisfaction with care reported by psychiatric inpatients: relationship to diagnosis and medical treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 87:374-379, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Lebow JL: Consumer satisfaction with mental health treatment. Psychological Bulletin 91:244-259, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Lebow JL: Client satisfaction with mental health treatment: methodological considerations in assessment. Evaluation Review 7:729-752, 1983Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Baronet AM, Gerber GJ: Client satisfaction in a community crisis centre. Evaluation and Program Planning 20:443-453, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar