Therapeutic Alliance and Psychiatric Severity as Predictors of Completion of Treatment for Opioid Dependence

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The role of patient characteristics and the strength of the therapeutic alliance in predicting completion of treatment by opioid-dependent patients was examined. METHODS: Information about patient characteristics and scores on subscales of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) were obtained for 114 patients at intake to a buprenorphine treatment program lasting three to four months. The strength of the therapeutic alliance was assessed by the Helping Alliance Questionnaire (HAQ). Patients were classified as treatment completers or noncompleters, and logistical regression examined predictors of treatment completion. RESULTS: Only two variables significantly predicted treatment completion: severity of psychiatric symptoms and interaction between HAQ scores and psychiatric severity. Patients with fewer psychiatric symptoms were more likely to complete treatment. The strength of the therapeutic alliance was not related to treatment completion among patients with few psychiatric symptoms, and 62 percent of these patients completed treatment. In contrast, among patients with moderate to severe psychiatric problems, less than 25 percent with weak therapeutic alliances completed treatment, while more than 75 percent with strong therapeutic alliances completed treatment. CONCLUSIONS: The results underscore the importance of early identification of opioid-dependent patients with moderate to severe levels of psychopathology. In this patient subgroup, a strong therapeutic alliance may be an essential condition for successful treatment.

Outpatient treatment for opioid dependence typically involves the administration of methadone or other opioid agonists such as buprenorphine or LAAM (L-alpha-acetyl-methadol). These opioid substitution agents ameliorate opioid withdrawal symptoms (1,2,3) and block the effects of other opioids (4,5), thereby reducing illicit opioid use (6,7). This reduction in illicit drug use results in concomitant decreases in drug-seeking and criminal behaviors (8,9), less HIV risk-taking behavior (10,11), and improvements in psychosocial functioning (6,12-15).

However, these beneficial effects of pharmacotherapy are achieved only when patients remain in treatment. Unfortunately, methadone and other treatment programs for opioid dependence are plagued by high rates of attrition. Estimates indicate that more than 50 percent of patients drop out or are discharged prematurely, often within the first three weeks of treatment (16,17,18,19).

The importance of retaining opioid-dependent patients in treatment programs has prompted a number of studies examining factors that may be associated with length of stay. Many of them are patient characteristics. Some variables that have been related to longer stays in treatment are less severe drug and alcohol use problems (19,20,21,22,23), better social supports (24), employment (25,26), fewer psychiatric problems (16,18,22,27), and no history of antisocial personality disorder (28,29,30,31). Although an understanding of patient characteristics may be useful in identifying patients who are likely to remain in treatment, these factors cannot be easily modified to improve retention.

One factor that can be altered to improve retention is the type or intensity of therapy provided in conjunction with the pharmacotherapy. Some evidence suggests that professional psychotherapy is more efficacious than drug abuse counseling in retaining opioid-dependent patients in treatment programs. Bickel and colleagues (32) showed that more than 50 percent of opioid-dependent patients assigned to multimodal behavioral therapy remained in treatment for the entire 26 weeks of outpatient detoxification with buprenorphine, compared with less than 25 percent of patients who received standard drug abuse counseling with detoxification.

McLellan and colleagues (33) found that 69 percent of patients assigned to receive only minimal counseling were prematurely discharged from methadone treatment. In contrast, no patients assigned to receive enhanced services consisting of counseling with on-site medical, psychiatric, employment, and family services were terminated early from treatment. Thus enhanced services provided in conjunction with pharmacotherapy may improve retention.

Some research suggests that patient characteristics may interact with psychotherapeutic variables to enhance retention and improve outcomes. Woody and colleagues (34) randomly assigned 110 opioid-dependent patients to one of three groups: drug counseling, drug counseling plus supportive-expressive therapy, or drug counseling plus cognitive-behavioral therapy. The two enhanced-therapy conditions were more efficacious than drug counseling alone (34), and pretreatment severity of psychiatric problems was related to outcomes across the treatment groups (35). Patients with few psychiatric symptoms made equivalent gains in treatment, regardless of their treatment condition. Patients with many psychiatric symptoms showed little improvement when assigned to drug counseling alone, but these patients made significant gains if they were assigned to one of the two psychotherapeutic conditions.

Woody and colleagues (36) confirmed these results in a subsequent study, treating only patients with more severe psychiatric problems. In a retrospective analysis of data from 741 drug- and alcohol-dependent patients, McLellan and colleagues (37) also showed that psychiatric severity was related to retention and outcome. Patients with few psychiatric problems were likely to remain in treatment and improve regardless of the type of treatment provided. However, patients with moderate psychiatric problems had different outcomes across treatments, and they tended to do better with specific patient-program matches.

To the extent that psychotherapy can enhance retention and improve outcomes, the patient and therapist must develop a meaningful rapport or a positive therapeutic alliance (38,39). Strong therapeutic alliances are associated with better response to treatment in a variety of psychiatric populations (38,39,40,41). Only two studies have examined the role of the therapeutic alliance in treating patients with opioid dependence. Luborsky and associates (39) found that a measure of the patient-therapist relationship taken early in treatment significantly correlated with treatment outcomes of methadone maintenance patients. Gerstley and colleagues (42) showed that the ability to form a strong alliance with a therapist was significantly and positively related to treatment success among methadone maintenance patients with antisocial personality disorder. Thus a strong therapeutic alliance may enhance retention and improve outcomes of difficult-to-treat patients.

The purpose of this study was to examine predictors of treatment completion, a proxy for retention, in an outpatient program for opioid dependence. We studied all patients who entered treatment over a two-year period and examined the role of demographic variables and the therapeutic alliance in predicting treatment completion among patients receiving an effective pharmacotherapy in conjunction with an intensive behavioral therapy. We hypothesized that certain pretreatment variables, including fewer psychiatric symptoms, would be associated with treatment completion. We also hypothesized that patients with a stronger therapeutic alliance would be more likely to complete treatment, and that this therapist-patient relationship would be particularly important for treatment completion among patients with more psychiatric problems.

Methods

Patients

The patients were 114 individuals, each enrolled in one of five buprenorphine studies—three studies of dosing and two of detoxification—conducted over a two-year period (1994 to 1996) at the University of Vermont Substance Abuse Treatment Center. Criteria for entry into the studies included being over 18 years old and meeting DSM-III-R criteria for opioid dependence and the Food and Drug Administration's qualification criteria for methadone treatment.

Psychiatric and medical status was determined by history, physical examination, and laboratory evaluation. Evidence of active untreated psychosis or serious medical illness (for example, cardiovascular or liver disease) and pregnancy were exclusion criteria. Codependence on other drugs did not exclude individuals from participation. In all studies, daily buprenorphine maintenance doses ranged from 2 to 8 mg per 70 kg of body weight, based on the level of opioid dependence (43). Subjects provided written informed consent after receiving a full explanation of the procedures.

Demographic and severity data

At patients' intake to the clinic, trained research assistants collected demographic information such as age, education, and gender and administered the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (44) to all patients. ASI severity scores, ranging from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicative of more severe problems, were derived for the subscales of alcohol, drug, medical, social, legal, employment, and psychiatric problems. In these subscales, severity is defined as the number, duration, frequency, and intensity of symptoms. Previous research indicates that interrater reliability coefficients are high, ranging from .84 to .95 across the seven subscales, and test-retest correlation coefficients are .92 or above (44). Discriminant validity is also adequate, with severity ratings on each of the subscales significantly correlating (p>.05) with other indexes of problems in that area (44).

Therapists

Three master's-level staff clinicians with degrees in counseling psychology or social work and seven to ten years of experience as therapists provided the therapy. They had been employed by the clinic for one and a half to two years, and each provided therapy to between 32 and 43 patients. Assignment was based on current clinical caseloads, so that new patients entering treatment were assigned to the therapist with the lightest clinical load. Therapists received two hours a week of group supervision and one hour a week of individual supervision. Therapists were blind to the purposes of this study.

Therapeutic alliance

The Helping Alliance Questionnaire—Therapist Version (HAQ-T) is a 19-item inventory that measures the alliance between therapists and their patients, or the degree of a positive, helping relationship (45). The items require responses from 1, strongly disagree, to 6, strongly agree. Five questions are negatively worded or related to negative interactions, and these items were reverse-coded. A total alliance score is computed by summing the responses, and scores can range from 19 to 114, with higher scores indicative of a more positive alliance.

This scale has adequate internal consistency, with correlations ranging from .90 to .93 (p>.001), and adequate test-retest reliability, with correlations ranging from .55 to .79 (p>) (45). It also has covergent validity with the California Psychotherapy Alliance Scale, with correlations ranging from .59 to .80 (p>001) (45).

The therapists completed the HAQ-T for each patient they saw for a minimum of three sessions. Only five patients were treated for less than three sessions, and they were not included in further analyses. For 46 of the 114 patients, the questionnaire was completed after the third therapy session. For the remainder of the patients, the questionnaire was completed retrospectively, after treatment termination. No statistically significant differences in HAQ-T ratings were noted between patients rated prospectively or retrospectively. The main analysis included the entire sample, and subsequent analyses were conducted including only patients for whom HAQ-T ratings were obtained after the third therapy session.

The Helping Alliance Questionnaire—Patient Version (HAQ-P) (45) asks the same questions as the HAQ-T, but from the patient's perspective. All but three of the 46 patients who were followed prospectively completed the HAQ-P after the third therapy session. Patients completed the questionnaire in the dispensary, which was in a separate location from therapists' offices so that therapists could not see their responses. Directions on the questionnaire indicated that responses would not be shared with therapists. Patients did not know that their therapists were rating the alliance.

Treatment completion

The two detoxification studies consisted of a four-month study period during which patients were given and then tapered off buprenorphine, followed by naltrexone. These studies required patients to attend the clinic a minimum of three times a week, receive medication, and attend one to two hours a week of individual behavioral therapy. Therapy focused on triggers of drug use, functional analyses of drug use, relapse prevention, coping strategies for cravings, drug refusal skills, HIV education, and social and recreational training. Specifically, patients were taught to monitor their triggers and cravings for drugs and to develop alternatives to drug use. Patients also chose from optional training modules. Among the choices were modules on employment, education, parenting, anxiety, depression, pain management, and insomnia. Patients were discharged for failure to receive buprenorphine on three consecutive days or failure to initiate naltrexone therapy after the buprenorphine taper.

The other three studies were buprenorphine pharmacology studies, ranging from three to four months (46,47,48). These studies examined different alternate-day dosing schedules of buprenorphine. Subjects were required to attend the clinic for all scheduled doses (between two and seven days a week), to remain abstinent from all opioids as assessed by urine specimens required two or three times a week, and to attend one to two hours a week of individual behavioral therapy, as described above. Subjects were discharged for failure to attend the clinic for a scheduled dose of buprenorphine or for submission of more than one opioid-positive urine sample.

Assignment to a detoxification or a pharmacology study was determined at intake to treatment by the clinic director, and it was based on the subject's preference and on the degree of opioid dependence. Patients with minimal levels of dependence were ineligible for pharmacology studies. Subjects were classified as study completers or noncompleters. No significant differences were noted between completion rates for detoxification and pharmacology studies; 62 percent completed detoxification and 53 percent completed pharmacology studies.

Data analysis

Differences between study completion rates, patient demographic characteristics, and baseline ASI scores were examined among the three therapists' caseloads using analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi square tests for nominal variables. Differences in HAQ-T and HAQ-P scores were also examined among the three therapists. To determine interrater reliability of ratings of alliances, correlations between patients' and therapists' alliance ratings were examined.

Univariate analyses were used to test differences between study completers and noncompleters in demographic characteristics, ASI severity ratings, and HAQ scores. These analyses were conducted using t tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for nominal variables.

Logistic regression was performed to examine unique contributions of these variables to whether subjects completed treatment. Demographic characteristics, ASI severity scores, clinic variables (study type, buprenorphine dose, and therapist), and HAQ-T scores and interactions of these variables were entered as independent variables. Treatment completion was the dependent variable.

Results

Comparison of therapists

The three therapists' caseloads did not differ in terms of any patient demographic characteristics or baseline ASI ratings. Study completion rates did not differ among the three therapists. Completion rates were 64 percent, 56 percent, and 47 percent for patients of therapists A, B, and C, respectively.

However, the therapists' ratings of their alliances with their patients differed significantly between therapists (F=4.01, df=2,113, p>.05). Therapist A had a mean±SD rating of 79±12 on the HAQ-T, which was significantly higher (p>.05) than those of the other two therapists. The mean±SD ratings were 74±10 and 69±23 for therapists B and C, respectively.

The strength of the therapeutic alliance as rated by the patients using the HAQ-P differed among the three therapists' patients, but the difference did not reach significance (p= .08). The highest mean±SD rating on the HAQ-P, of 96±14, was for therapist B, and the lowest, of 81±20, was for therapist A; the mean rating for therapist C, of 88±,17, was in between. Although patients tended to give higher ratings to the alliances than the therapists did, the therapists' and patients' ratings were related, with correlations between HAQ-P and HAQ-T scores ranging from .64 to .73 (p>.05).

Comparison of completers and noncompleters

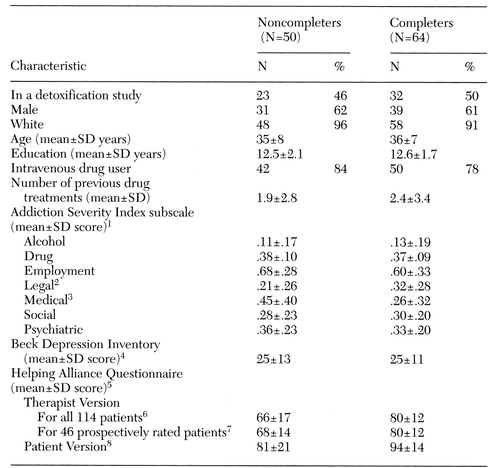

Table 1 presents characteristics of the study completers and noncompleters. The groups did not differ significantly in basic demographic characteristics, including gender, race, age, and education. A similar proportion of each group were intravenous drug users. The completers and noncompleters differed significantly on only two of 15 variables tested, ASI scores for legal and medical problems. Those who completed the studies had more severe legal problems and less severe medical problems.

Completers and noncompleters also differed significantly in the strength of the therapeutic alliance as rated by both the therapists and the patients. Compared with noncompleters, patients who completed treatment rated alliances higher, as did their therapists.

Logistic regression

Table 2 shows the initial and final models testing the association of treatment completion status and certain variables, including ASI scores. The general procedure used in the development of the logistic regression model incorporated several steps to determine variables for inclusion in the final model. The first step was to enter basic characteristics and ASI severity ratings as one block into the logistic regression equation. For variables that were highly correlated with one another, such as employment and severity of legal problems, only one was included. The second step was to enter program variables into the equation, after controlling for the demographic characteristics. In the third step, the therapists' alliance ratings and the interaction between psychiatric severity and therapeutic alliance were entered.

Several iterations of model trimming were done to develop the most parsimonious model. Parameters not approaching statistical significance were dropped. After variables that best explained the variance were identified, variables that had been excluded from the original analysis due to multicollinearity (such as ASI ratings on employment and legal problems, and the ASI rating on drug problems and intravenous drug use) were substituted into the equation, and analyses were rerun.

Model 1 included age, education, gender, and intravenous drug use and only three ASI ratings—alcohol, legal, and psychiatric severity scores. The three subscales were chosen because they have been associated with treatment retention in previous studies (19,20,21,37) and because they did not correlate with one another. Gender and intravenous drug use were coded as dummy variables. The likelihood ratio test indicated that this model did not predict study completion.

Model 2 addressed whether program-specific variables (therapist assignment, type of study protocol, and buprenorphine dose) predicted completion status, after controlling for the previously described variables. The likelihood ratio test indicated that this model also failed to predict study completion.

Model 3 examined whether therapists' ratings of the alliance (HAQ-T scores) and the interaction between the therapeutic alliance and psychiatric severity were significantly associated with treatment completion, after controlling for the other variables. Inclusion of this step resulted in an equation that significantly predicted treatment completion (χ2=37.5, df= 13, p>.001 for the model, and χ2= 27.3, df=2, p>.001 for the block). More than 75 percent of the cases were correctly identified by this model as completers or noncompleters.

After other variables were adjusted, ASI scores on psychiatric severity were significantly related to treatment completion (Wald statistic= 4.80, p>.05), and patients with fewer psychiatric symptoms were more likely to complete treatment. When the analysis adjusted for other variables, therapeutic alliance was not associated with completion status, but the interaction between psychiatric severity and therapeutic alliance was associated (Wald statistic=4.25, p>.05). Patients with more severe psychiatric symptoms were more likely to complete treatment if they had a strong alliance, but alliance was not related to completion among patients with less severe psychiatric symptoms.

These models were repeated removing terms that were not significantly associated with treatment completion. Both the initial and the final models are shown in Table 2. The final model was robust, in that key variables of interest did not vary appreciably with inclusion or exclusion of other variables, such as adding ASI scores on the drug or social subscales; substitution of other highly correlated variables, such as legal ASI score for employment ASI score; or removal of nonsignificant variables, such as gender, education, intravenous drug use, and buprenorphine dose. Although other possible interactions between alliance measures and other variables were examined, none were significant.

Interaction between psychiatric severity and alliance

Patients were grouped into one of three categories based on psychiatric severity, with 38 patients in each group: those with ASI scores in the lowest third of the sample (scores of 0 to .21), in the middle third (scores of .22 to .48), or in the highest third (scores of .49 to 1). The alliance between the therapists and each of their patients was ranked as either above or below the median of the alliances for that therapist.

Figure 1 shows that therapeutic alliance did not affect study completion among patients with few psychiatric symptoms. However, the therapeutic alliance was related to treatment completion among patients who had psychiatric problems that were moderate or severe. Only 23 percent of patients with moderate to severe psychiatric symptoms and a below-average alliance completed treatment. In contrast, more than 75 percent of patients with moderate to severe psychiatric problems but an above-average alliance completed treatment. This trend was similar for all three therapists (data not shown).

The interaction effect was maintained when the analysis included only the 46 patients who were followed prospectively. HAQ-T scores were not related to study completion of patients with relatively few psychiatric symptoms. However, among patients with moderate to severe psychiatric problems, 30 percent with low-rated alliances completed treatment versus 80 percent with high-rated alliances. Chi square analyses revealed that alliance was significantly associated with treatment completion among patients with moderate to severe psychiatric problems (χ2=8, df= 1, p<.01).

Among the 46 patients followed prospectively, 43 completed the HAQ-P. Analysis of their ratings of the therapeutic alliance provided further support for these findings. HAQ-P scores were not associated with treatment completion among patients with few psychiatric problems. Seventy-five percent of those with alliances below the median completed treatment, and 67 percent of those with alliances above the median completed treatment. Among those with moderate and severe psychiatric problems, the relationship between study completion and therapeutic alliance approached but did not reach statistical significance (p=.06). Fifty percent of patients who reported relatively weak alliances completed treatment versus 85 percent of those who reported relatively strong alliances.

Discussion and conclusions

This study examined the relationship between patient variables, ASI severity ratings, program-specific variables, and the therapeutic alliance in predicting treatment completion among opioid-dependent individuals in an outpatient research and treatment clinic. The data indicate that only psychiatric severity and the interaction between psychiatric severity and therapeutic alliance predicted treatment completion. These findings, and several issues that may bear on the interpretation of the findings, are discussed.

The three therapists' caseloads did not differ in any demographic characteristics or ASI severity ratings. This lack of difference was expected, because new patients were arbitrarily assigned to therapists. In addition, treatment completion rates did not differ among the three therapists' caseloads, suggesting that the three therapists were equally efficacious in retaining patients in the studies.

However, significant differences in HAQ-T scores were noted among the three therapists. These differences suggest either that the three therapists had differential response biases in filling out the questionnaire (for example, therapist A was most likely to strongly endorse positive items) or that the alliances between patients and therapists differed among the three therapists. Patients' ratings indicated that therapist B tended to have the strongest relationships with patients and therapist A the weakest. Because of these differences in HAQ ratings among the therapists, subsequent analyses controlled for a therapist effect.

To examine the unique variance that therapeutic alliance, patient characteristics, and symptom severity may explain in predicting treatment completion, logistic regression analysis was conducted. After the analysis controlled for other variables, only psychiatric severity and the interaction between psychiatric severity and therapeutic alliance significantly predicted treatment completion. Specifically, patients with moderate to severe psychiatric symptoms were less likely to complete treatment. The interaction term indicated that patients with few psychiatric problems were equally likely to complete treatment, regardless of whether they had strong or weak alliances with their therapists. In contrast, a strong alliance was associated with a completion rate three times higher among patients who presented with moderate to severe psychiatric symptoms.

These results both confirm and extend previous findings of the roles of psychiatric severity and therapeutic alliance in treatment retention. Several studies of substance abusers have found better retention rates among those with fewer baseline psychiatric problems (35,36,37). In terms of the role of the therapeutic alliance, Luborsky and colleagues (39,41) have shown repeatedly the predictive validity of the HAQ in the treatment responsiveness of substance abusers as well as other psychiatric populations. The data from the study reported here integrate these findings and suggest that the therapeutic alliance is particularly important in predicting treatment retention among opioid-dependent individuals with moderate to severe psychiatric problems.

These results are consistent with those recently reported by Carroll and colleagues (49). They found that a strong alliance was important in treatment outcome among cocaine-dependent patients assigned to "control" therapies, but alliance did not predict outcome among patients assigned to enhanced therapies. To the extent that receiving enhanced therapies, like having few psychiatric problems, leads to improved outcomes, a strong alliance seems to exert influence on outcome among patients who are less likely to succeed on their own. Whether these results hold for other substance-abusing and psychiatric populations remains to be determined.

Although these conclusions have intuitive appeal and are consistent with past research, the findings may be affected by several factors. One potential criticism of these findings is that the ASI psychiatric composite score, rather than structured clinical diagnoses, was used to assess psychiatric status. However, this scale score is highly correlated with scores on the Beck Depression Inventory, the Maudsley neuroticism scale, and the Symptom Checklist-90 (37). In the study reported here, pretreatment Global Severity Index scores from the Symptom Checklist-90 were available for 77 patients and correlated (r2=.46, p<.001) with ASI psychiatric scores. Thus in both this sample and previous samples of opioid-dependent patients, ASI psychiatric scores are indicative of global psychiatric status. However, patients with the most severe psychiatric problems, such as active psychosis, were screened out before admission to treatment or may have been discharged before receiving three therapy sessions. Thus these findings are representative only of patients who remained in treatment at least two weeks.

One weakness of the study was that the therapeutic alliance was retrospectively rated for the majority of the patients and thus may have been influenced by therapists' knowledge of whether the patient completed treatment. Similarly, patients who were retained in treatment longer may have been more likely to develop a stronger relationship with their therapist. However, post hoc analyses including only patients who were followed prospectively confirmed the main finding of a stronger alliance being important for successful treatment completion among patients with moderate to severe psychiatric problems. Other prospective research using the HAQ also indicates that both therapists and patients have an early mutual sense of the therapeutic alliance and that does not change appreciably over time (45).

Another potential limitation of the findings is that the dependent variable of interest was defined as a dichotomous variable: completion or noncompletion of a three- to four-month research study. Other studies have used pre- and posttreatment evaluations of drug use and psychosocial functioning as outcome measures (16,18,22,2735,36,44), and these measures may better assess efficacy of treatment across a range of domains. In the study reported here, such data were not collected for all subjects across all trials, and thus treatment completion was used as the dependent variable. Nevertheless, completion of a three- to four-month treatment program such as the protocols in which these subjects participated may be considered a clinically important outcome measure. In previous studies, Simpson and colleagues (50,51,52) found that drug abusers who spent less than three months in treatment programs had the least favorable outcomes.

In the study reported here, subjects were required to attend the clinic regularly and provide opioid-negative urine samples to be permitted to continue in these trials for three to four months. The bulk of evidence suggests that treatment retention in opioid substitution programs is associated with a variety of positive outcomes, including reductions in opioid and other illicit drug use (6), decreases in criminal activity (9), improvements in psychosocial functioning (12), and reductions in HIV risk-taking behaviors (10). Further research may more clearly delineate the effects of the therapeutic alliance and psychiatric symptoms in improving these variables during substance abuse treatment.

Other limitations of this study include the small sample size of therapists and the research nature of the clinic in which the study was conducted. Only three therapists were studied, but similar trends were found for all three. In other words, all three equally retained patients with few psychiatric symptoms in the research protocols, regardless of the alliance.

In addition, for patients with moderate and high levels of psychopathology, increases in study completion rates were found for all three therapists only when a strong relationship was formed. These similar results across therapists may have resulted from the highly structured therapy that was provided in conjunction with buprenorphine, an efficacious opioid agonist. Future research should examine whether these results can be replicated with a larger sample of less experienced therapists and when other psychotherapies are provided, both with and without pharmacotherapy.

In summary, these data indicate that psychiatric severity and the interaction between psychiatric severity and therapeutic alliance are associated with treatment completion among opioid-dependent individuals. If the results are replicated in prospective studies using a larger sample of therapists and a greater variety of outcome measures, they may have important implications for treating opioid-dependent individuals.

Specifically, the results suggest that patients with few psychiatric problems tend to stay in treatment, regardless of their relationship with their therapist. However, perhaps greater efforts should be expended on developing a positive helping alliance with patients who have moderate and severe psychiatric problems. The data indicate that these patients are not likely to remain in treatment unless they develop a strong therapeutic relationship with their therapist.

Because the helping alliance is established by the third therapy session (45), patients with psychiatric problems should be closely monitored. Perhaps patients who do not develop a positive relationship early in treatment could be transferred to a new therapist, with whom they may be more likely to develop a positive rapport. Prospective clinical trials are needed to assess this strategy in improving retention in substance abuse treatment programs.

Although this study did not have an adequate sample of therapists and patients to investigate demographic and other personal qualities of both that may be relevant to a strong alliance, other studies have begun to address this issue. These factors may include demographic similarities between patient and therapist (53), the patient's degree of involvement in therapy (54), and mutual patient-therapist understanding (55).

A better understanding of the characteristics and processes that result in the development of a positive therapeutic alliance may help improve treatment retention of opioid-dependent patients, especially those with greater psychiatric problems, who are among the most difficult to treat. Given the high prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders and early treatment termination among substance abusers (17), the drug abuse treatment and public health communities may benefit from expanded efforts to understand and maximize the effectiveness of dynamic patient-therapist variables that are associated with retention in treatment programs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bruce Brown, M.S.W., Marne Moegelin, M.A., and Tyler Wood, M.A., for providing therapy, Melissa Foster, Elizabeth Kubik, Bonnie Martin, Richard Taylor, and Evan Tzanis for collecting data, and Alan Budney, Ph.D., Joe Burelson, Ph.D., Henry Kranzler, M.D., and Howard Tennen, Ph.D., for providing helpful comments. This research was supported by grants T32DA07242, R01DA06969, 2R01DA06969-Supp, and R29DA12056 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and grant 5P50-AA03510-19 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

When this work was done, Dr. Petry and Dr. Bickel were affiliated with the Substance Abuse Treatment Center and the departments of psychology and psychiatry at the University of Vermont in Burlington. Dr. Petry is now affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Connecticut Health Center, 263 Farmington Avenue, Farmington, Connecticut 06030-2103 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Percentage of opioid-dependent patients completing treatment as a function of psychiatric severity and therapeutic alliance

|

Table 1. Characteristics of opioid-dependent patients who did not complete and completed buprenorphine treatment

1Possible scores range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating more severe problems.

2t=2.25, df=112, p<.05 for the difference between completers and noncompleters

3t=3.01, df=112, p<.01 for the difference between completers and noncompleters

4Possible scores range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating more severe problems.

5Possible scores range from 19 to 114, with higher scores indicating a strong alliance.

6t=5.05, df=112, p<.001 for the difference between completers and noncompleters

7t=2.94, df=112, p<.01 for the difference between completers and noncompleters

8Forty-three patients completed the questionnaire; t=2.26, df=41, p<.05, for the difference between completers and noncompleters

|

Table 2. Initial and final models of logistic regression analyses predicting buprenorphine treatment completion among opioid-dependent patients

1OR=.17,95% CI=.03 to .83, p<.05

2OR=1.02,95% CI=1 to 1.04, p<.05

3OR=.20,95% CI=.05 to .83, p<.05

1. Bickel WK, Amass L: Buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence: a review. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 3:477-489, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Bickel WK, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE, et al: A clinical trial of buprenorphine: comparison with methadone in the detoxification of heroin addicts. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapy 43:72-78, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Ling W, Charuvastra VC, Kaim SC, et al: Methadyl acetate and methadone as maintenance treatments for heroin addicts. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:709-720, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Bickel WK, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE, et al: Buprenorphine: dose-related blockade of opioid challenge effects in opioid dependent humans. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapy 247:47-53, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

5. Rosen MI, Wallace EA, McMahon TJ, et al: Buprenorphine: duration of blockade of effects of intramuscular hydromorphone. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 35:141-149, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Ball JC, Ross A: The Effectiveness of Methadone Maintenance Treatment. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1991Google Scholar

7. Strain EC, Stitzer ML, Liebson IA, et al: Comparison of buprenorphine and methadone in the treatment of opioid dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1025-1030, 1994Link, Google Scholar

8. Ball JC, Rosen L, Flueck J, et al: The criminality of heroin addicts when addicted and when off opiates, in The Drug-Crime Connection. Edited by Inciardi JA. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage, 1981Google Scholar

9. Nurco DN, Shaffer JW, Ball JC, et al: Trends in the commission of crime among narcotic addicts over successive periods of addiction and nonaddiction. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 10:481-489, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Metzger DS, Woody GE, McLellan AT, et al: Human immunodeficiency virus seroconversion among intravenous drug users in and out of treatment: an 18-month prospective follow-up. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 6:1049-1056, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

11. Saxon AJ, Calsyn DA, Jackson TR: Longitudinal changes in injection behaviors in a cohort of injection drug users. Addiction 89:191-202, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, O'Brien CP, et al: Is treatment for substance abuse effective? JAMA 247:1423-1427, 1982Google Scholar

13. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, O'Brien CP, et al: Alcohol and drug abuse treatment in three difference populations: is there improvement and is it predictable? American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 12:101-120, 1986Google Scholar

14. Simpson DD: The relation of time spent in drug abuse treatment to posttreatment outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry 136:1449-1453, 1979Link, Google Scholar

15. Rounsaville BJ, Kosten TR, Kleber HD: The antecedents and benefits of achieving abstinence in opioid addicts: a 2.5-year follow-up study. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 13:213-229, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Baekland F, Lundwall L: Dropping out of treatment: a critical review. Psychology Bulletin 82:738-783, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Hubbard RL, Marsden ME, Rachal JV: Drug Abuse Treatment: A National Study of Effectiveness. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Press, 1989Google Scholar

18. Stark MJ: Dropping out of substance abuse treatment: a clinically oriented review. Clinical Psychology Review 12:93-116, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Stark MJ, Campbell BK: Personality, drug use, and early attrition from substance abuse treatment. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 14:475-485, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Aron WS, Daily DW: Graduates and splitees from therapeutic community drug treatment programs: a comparison. International Journal of Addiction 11:1-18, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Beck NC: Prediction of discharges against medical advice from an alcohol and drug misuse treatment program. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 44:171-180, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Beckman LJ, Bardsley PE: Individual characteristics, gender differences and drop-out from alcoholism treatment. Alcohol and Alcoholism 21:213-224, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

23. Noel NE, McCrady BS, Stout RL, et al: Predictors of attrition from an outpatient alcoholism treatment program for couples. Journal of Studies on Alcoholism 3:229-235, 1987Google Scholar

24. Havassy BE, Hall SM, Wasserman DA: Social support and relapse: commonalities among alcoholics, opiate users, and cigarette smokers. Addictive Behavior 16:235-246, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

25. McLellan AT: Patient characteristics associated with outcome, in Research on the Treatment of Narcotic Addiction: State of the Art. Edited by Cooper JR, Altman F, Brown BS, et al. NIDA Treatment Research Monograph Series, no ADM 83-1281. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1983Google Scholar

26. Joe GW, Simpson DD: Retention in treatment of drug users:1971-1972 DARP admissions. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 2:63-71, 1975Google Scholar

27. Robinson KD, Little GL: One-day dropout from correctional drug treatment. Psychological Reports 51:409-410, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Alterman AI, Cacciola JS: The antisocial personality disorder diagnosis in substance abusers: problems and issues. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 179:401-409, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Kranzler HR, Del Boca FK, Rounsaville BJ: Comorbid psychiatric diagnosis predicts three-year outcomes in alcoholics: a posttreatment natural history study. Journal of Studies on Alcoholism 57:619-626, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Hesselbrock V, Meyer R, Keener J: Psychopathology in hospitalized alcoholics. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:1050-1055, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Schuckit MA: The clinical implications of primary diagnostic groups among alcoholics. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:1043-1049, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

32. Bickel WK, Amass L, Higgins ST, et al: Effects of behavioral treatment during opioid detoxification with buprenorphine. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65:803-810, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. McLellan AT, Arndt IO, Metzger DS, et al: The effects of psychosocial services in substance abuse treatment. JAMA 269:1953-1959, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Woody GE, Luborsky L, McLellan AT, et al: Psychotherapy for opiate addicts: does it help? Archives of General Psychiatry 40:639-645, 1983Google Scholar

35. Woody GE, McLellan AT, Luborsky L, et al: Severity of psychiatric symptoms as a predictor of benefits from psychotherapy: the Veterans Administration-Penn study. American Journal of Psychiatry 141:1172-1177, 1984Link, Google Scholar

36. Woody GE, McLellan AT, Luborsky L, et al: Psychotherapy in community methadone programs: a validation study. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1302-1308, 1995Link, Google Scholar

37. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al: Predicting response to alcohol and drug abuse treatments: role of psychiatric severity. Archives of General Psychiatry 40:620-625, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Horvath AO, Symonds BD: Relation between working alliance and outcome in psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology 38:139-149, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Luborsky L, McLellan AT, Woody GE, et al: Therapist success and its determinants. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:602-611, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Luborsky L, Auerbach AH: The therapeutic relationship in psychodynamic psychotherapy: the research evidence and its meaning for practice, in Psychiatry Update: American Psychiatric Association Annual Review, vol 4. Edited by Hales RE, Frances AJ. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1985Google Scholar

41. Horvath AO, Luborsky L: The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 4:561-573, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

42. Gerstley K, McLellan T, Alterman AI, et al: Ability to form an alliance with the therapist: a possible marker of prognosis for patients with antisocial personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:508-512, 1989Link, Google Scholar

43. Amass L, Bickel WK, Higgins ST, et al: Alternate-day dosing during buprenorphine treatment of opioid dependence. Life Sciences 54:1215-1228, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, et al: New data from the Addiction Severity Index: reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 173:412-423, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

45. Luborsky L, Barber JP, Siqueland L, et al: The revised Helping Alliance Questionnaire (HAQ-II): psychometric properties. Journal of Psychotherapeutic Practice and Research 5:260-271, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

46. Bickel W, Petry NM, Tzanis E: The limits of alternate day buprenorphine dosing, in Problems of Drug Dependence, 1996. Edited by Harris LS. NIDA Research Monograph no 174. DHHS pub (NIH) 97-4236. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1997Google Scholar

47. Petry NM, Bickel WK: Buprenorphine self-administration in opioid-dependent outpatients: effects of an alternative reinforcer, behavioral economic analysis of demand, and comparison of subjective and reinforcing drug effects. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, in pressGoogle Scholar

48. Petry NM, Bickel WK, Tzanis E: Quadruple buprenorphine doses maintain opioid-dependent outpatients for 96 hours with minimal withdrawal, in Problems of Drug Dependence, 1996. Edited by Harris LS. NIDA Research Monograph no 174. DHHS pub (NIH) 97-4236. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1997Google Scholar

49. Carroll KM, Nich C, Rounsaville BJ: Contribution of the therapeutic alliance to outcome in active versus control psychotherapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 65:510-514, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Simpson DD, Savage LJ, Flody MR: Follow-up evaluation of treatment of drug abuse during 1969-1972. Archives of General Psychiatry 36:772-780, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Simpson DD: Treatment for drug abuse: follow-up outcomes and length of time spent. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:875-880, 1981Crossref, Google Scholar

52. Simpson DD, Sells SB: Effectiveness of treatment for drug abuse: an overview of the DARP research program. Advances in Alcohol and Substance Abuse 2:7-29, 1982Crossref, Google Scholar

53. Alexander L, Luborsky L: Research on the helping alliance, in The Psychotherapeutic Process: A Research Handbook. Edited by Greenberg L, Pinsof W. New York, Guilford, 1984Google Scholar

54. Gomes-Schwartz B: Effective ingredients in psychotherapy: predictions of outcome from process variables. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 46:123-135, 1978Google Scholar

55. Saltzman C, Luetgert M, Roth C, et al: Formation of a therapeutic relationship: experiences during the initial phase of psychotherapy as predictors of treatment duration and outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 44:546-555, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar