Psychiatric Illness and Comorbidity Among Adult Male Jail Detainees in Drug Treatment

Abstract

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders was examined in a sample of 204 pretrial jail detainees receiving standard drug treatment. More than half of the sample had at least one lifetime DSM-III-R axis I diagnosis, and the lifetime rates of serious mental illness were higher than reported prevalence rates for arrestees in general jail populations. Detainees with comorbid disorders were more likely than others to have more than one co-occurring psychiatric disorder, to have been arrested for property crimes, and to be dependent on alcohol, marijuana, or PCP. The findings argue for the expansion of integrated treatment services within criminal justice drug treatment settings.

Offenders addicted to alcohol and other drugs likely have high rates of comorbid psychiatric disorders. Even so, drug treatment programs in the criminal justice system have focused on treating drug dependence and have not addressed the issue of psychiatric comorbidity commensurate with the extent of the problem (1).

Drug treatment programs in the criminal justice system treat comorbid psychiatric disorders as additional problems to be addressed while attending to the main clinical task of dealing with addiction to alcohol or other drugs (2). However, research suggests that addicted persons with comorbid psychiatric disorders follow clinical courses distinct from those of persons with single disorders (3,4). In particular, those with comorbid severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia, manic-depression, and major depression are more difficult to treat, require more intensive services, are at increased risk for HIV infection, and have poorer outcomes (3,4,5).

Although some studies have looked at the prevalence of psychiatric illness in general prison or jail populations (6), few have examined the prevalence of psychiatric illness among offenders in drug treatment programs. Because offenders already in drug treatment likely have high rates of psychiatric comorbidity and because they can be engaged most expediently in specialized programming, this study attempted to determine the prevalence of undetected comorbid psychiatric disorders among addicted offenders in treatment. It also compared addicted offenders with and without comorbid disorders on patterns of drug use, criminal behavior, other psychiatric diagnoses, and treatment outcomes.

Methods

Convenience sampling was used to recruit 211 adult male arrestees receiving drug treatment at the day reporting center of the Cook County, Chicago, jail between February and May 1997. A detailed description of the treatment program has been published elsewhere (7). Briefly, day reporting center participants assessed as having a substance use problem are required to attend at least two hours of group therapy daily, up to the duration of their stay. The therapy is based on a modified therapeutic community model, heavily incorporating principles of Alcoholics Anonymous.

Interviews were completed with 204 participants (97 percent). Comparative analyses yielded only one significant demographic difference between the sample and others in the program during the same time period. The sample had a larger proportion of African Americans; 93 percent in the study sample compared with 83 percent in the program population.

Psychiatric diagnoses were obtained from the Quick Diagnostic Interview Schedule (QDIS). The QDIS is a computer-administered shortened version of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) developed to yield accurate lifetime and past-year DSM-III-R diagnoses for 27 psychiatric disorders (8). Additional variables included drug use measured by urinalysis at admission; arrest history data, which were available for 169 participants, or 83 percent of the sample; and treatment outcomes from program records.

Results

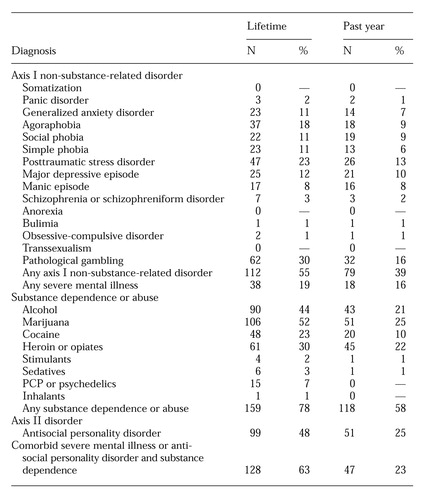

As Table 1 shows, 112 of the 204 participants (55 percent) had one or more DSM-III-R axis I lifetime diagnoses, while 38 (19 percent) met lifetime criteria for a severe mental illness. All lifetime and past-year rates of severe mental illness were significantly elevated compared with prevalence rates for adult males in the general population found in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study and the National Comorbidity Survey (6,9). Moreover, our sample's lifetime and past-year prevalence rates of a manic episode and a major depressive episode were also elevated compared with rates for these disorders in a general population of male jail detainees (10).

Among the 112 participants with a lifetime diagnosis of either a severe mental illness or antisocial personality disorder (55 percent of the sample), 100 participants (89 percent) had comorbid substance dependence or abuse. In comparison, of the 92 participants who did not have a lifetime diagnosis of severe mental illness or antisocial personality disorder, 59 (64 percent) had ever abused or been dependent on substances (χ2=18.6, df=1, p<.001). Alternatively, the rate of severe mental illness or antisocial personality disorder among those with a lifetime diagnosis of drug dependence or abuse was 63 percent, compared with a rate of only 23 percent among participants who had not abused or been dependent on drugs. Either perspective reveals a significant correlation between severe mental illness and antisocial personality disorder and drug abuse and dependence.

We next examined differences between three subgroups of participants. In one group—the group with no diagnoses—were 33 participants who had neither a current or lifetime diagnosis of substance dependence or abuse nor a current or lifetime diagnosis of severe mental illness or antisocial personality disorder. In the second group—the substance-dependent group—were 59 participants who had a lifetime diagnosis of substance dependence or abuse but no lifetime diagnosis of severe mental illness or antisocial personality disorder. In the third group—the group with comorbid disorders—were 100 participants with a lifetime diagnosis of substance dependence or abuse and a lifetime diagnosis of severe mental illness or antisocial personality disorder. (Twelve participants had a lifetime diagnosis of antisocial personality disorder but did not have a comorbid substance use disorder. This group was too small for analysis and was dropped.)

We examined differences between these groups in the number and type of previous arrests, lifetime DSM-III- R axis I psychiatric diagnoses that were not severe mental illnesses, lifetime DSM-III-R diagnoses of drug dependence and abuse (for the two groups that included individuals with substance use disorders), and current drug use. Analyses of covariance controlling for age revealed that the substance-dependent group and the group with comorbid disorders had a higher mean number of previous arrests than the group with no psychiatric or substance use diagnoses (F=3.5, df=2,154, p=.03).

The substance-dependent participants had been arrested more often for drug-related offenses than participants in the other two groups (F=3.8, df=2,154, p=.02). The group with comorbid disorders had a higher mean number of arrests for property offenses than the other two groups (F=3.4, df=2,154, p=.035).

The proportion of participants with a DSM-III-R axis I psychiatric diagnosis other than severe mental illness was highest in the group with comorbid disorders across the entire range of assessed disorders; 72 percent of this group had at least one additional axis I disorder. In comparison, 49 percent of the substance-dependent group and 30 percent of the group with no diagnoses had at least one additional axis I disorder (χ2=20.3, df=2, p<.001, N=192).

The same pattern of more severe pathology among participants with comorbid disorders extended to dependence on or abuse of alcohol (χ2=11, df=1, p=.001, N=159), marijuana (χ2=36.4, df=1, p<.001, N=159), and PCP (χ2=4, df=1, p<.05, N=159). The exceptions to this pattern were that the substance-dependent group had higher rates of heroin and opiate dependence (χ2=10, df=1, p=.002, N=159) and heroin use (χ2=17.2, df=2, p<.001, N=192) than the comorbid group at program admission. In addition, even though no lifetime diagnostic differences in cocaine dependence or abuse were found between the substance-dependent group and the comorbid group, participants in the substance-dependent group were significantly more likely to be using cocaine at admission (χ2=8.6, df=2, p=.01, N=192).

The three groups did not differ significantly in discharge outcomes. This finding could be attributed to the fact that many factors besides clinical differences can determine program outcome. For example, when cases were adjudicated or bond was posted, participants left the program.

Discussion and conclusions

Our results show that many offenders participating in nonspecialized drug treatment programs are likely to have a serious comorbid psychiatric disorder. As in studies of the general population (9), we also found that serious comorbid psychiatric disorders tend to cluster in individuals with other psychiatric disorders. Two distinct groups emerged in our analyses. The first comprised substance-dependent participants with no comorbid psychiatric disorders who would be most appropriate for traditional drug treatment programming. These individuals tended to be arrested for drug-related crimes, to be dependent on or abusing heroin and opiates, and to be using both heroin and cocaine at higher rates than those with a comorbid disorder.

A second group consisted of substance-dependent individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders who were more likely to have been arrested for property offenses and to be dependent on or abusing alcohol, marijuana, or PCP. These participants had multiple and more severe psychopathologies and were most in need of specialized programming.

Currently only a small number of programs exist in the criminal justice system for chemically dependent persons with mental illnesses. However, our data indicate that screening and treatment services specifically for addicted offenders with severe psychiatric comorbidities should be considerably expanded. Integrated treatment programs such as those as described by El-Mallakh (3) and Mueser and colleagues (4) are especially rare but especially needed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Scott Slomka, B.A., for managing data collection and preparation and Demetria Warren for conducting the interviews.

Dr. Swartz is director of research and information services at Illinois Treatment Alternatives for Safe Communities, Inc., 1500 North Halsted Street, Chicago, Illinois 60622 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Lurigio is professor and chair of the department of criminal justice at Loyola University in Chicago. This paper is part of a special section on mentally ill offenders.

|

Table 1. DSM-III-R lifetime and past-year diagnoses among 204 adult male jail detainees in drug treatment

1. Edens JF, Peters RH, Hills HA: Treating prison inmates with co-occurring disorders: an integrative review of existing programs. Behavioral Science and Law 15:439-457, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Peters R: Drug treatment in jails and detention settings, in Drug Treatment and Criminal Justice. Edited by Inciardi J. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage, 1993Google Scholar

3. El-Mallakh P: Treatment models for clients with co-occurring addictive and mental disorders. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 12:71-80, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mueser KT, Drake RE, Miles KM: The course and treatment of substance use disorders in persons with severe mental illness, in Treatment of Drug-Dependent Individuals With Comorbid Mental Disorders. NIH pub 97-4172. Edited by Onken LS, Blaine JD, Genser S, et al. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1997Google Scholar

5. Cournos F, McKinnon K: HIV seroprevalence among people with severe mental illness in the United States: a critical review. Clinical Psychology Review 17:259-269, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DA, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA 264:2511-2518, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Lurigio AJ, Olson DE, Swartz J: Chicago day-reporting center reduces pretrial detention, drug use, and absconding. Overcrowded Times, June 1998, pp 1, 6-9Google Scholar

8. Bucholz KK, Marion SL, Shayka JJ, et al: A short computer interview for obtaining psychiatric diagnoses. Psychiatric Services 47:293-297, 1996Link, Google Scholar

9. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Teplin LA: Psychiatric and substance abuse disorders among male urban jail detainees. American Journal of Public Health 84:290-293, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar