Use of the Balanced Scorecard to Improve the Quality of Behavioral Health Care

Abstract

As the debate over managed care continues, measuring quality has increasingly become a focus in health care. One approach to measuring quality is the use of a scorecard, which summarizes a critical set of indicators that measure the quality of care. The author describes the Balanced Scorecard (BSC), a tool developed for use in businesses to implement strategic plans for meeting an organization's objectives, and shows how the BSC can be adapted for use in behavioral health care. The scorecard addresses quality of care at five levels: financial, customer, outcomes, internal processes, and learning and growth. No more than four or five realistic objectives are chosen at each level, and an indicator for the achievement of each objective is designed. The BSC integrates indicators at the five levels to help organizations guide implementation of strategic planning, report on critical outcomes, and offer a report card for payers and consumers to make informed choices.

As a consequence of health care payers' revolt in the 1980s, providers of health care in the United States have been concerned with costs in the 1990s. Managed care has been perceived as mainly a cost containment strategy. A widespread perception exists that the quality of care has deteriorated under managed care; however, it is based on the assumption that we can measure quality with a reasonable degree of accuracy and reliability (1,2,3).

Measuring quality and its relationship to cost is slowly becoming a central issue in U.S. health care policy in general and in psychiatry in particular (4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12). Value, a function of quality, cost, and patient satisfaction, must be measured to help payers and insured populations make informed choices and to assess the potential consequences of the choices that are available (13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21). Private and public agencies have been charged with the tasks of defining and assessing quality. Organizations, groups of professionals, and individual clinicians will be held accountable for the value of the services delivered. Clinicians and administrators must define quality and demonstrate results in a way that can be easily understood by all parties.

The challenges are multiple, and I will attempt to address some of them in this paper. First and foremost is the need to identify indicators that measure quality. Second is the need to understand the design of quality indicators so that they assess the critical aspects of quality. The third need is to understand how these measurements are causally linked to each other, leading to the desired results. Fourth, and not necessarily last, is the need to decide what we will do with these measurements and how they will serve patients, health care providers, employers, insurers, and policy makers.

Quality measurement

Current efforts

Several efforts at the national level are focusing on defining and measuring quality (22). Initiatives to measure quality and cost of mental health and substance abuse services have been sponsored by the Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) (23), the American Managed Behavioral Healthcare Association, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through the U.S. Public Health Service.

In 1997 the American College of Mental Health Administrators held a summit meeting in Santa Fe, New Mexico, that was focused on drafting a scorecard for behavioral health services (22). The National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors is endorsing initiatives to measure quality in several states. A number of other agencies, such as the Utilization Review Accreditation Commission, the Council on Accreditation of Services for Families and Children, and the Rehabilitation Accreditation Commission, are all engaged in similar efforts to measure quality in their areas, including the quality of mental health services.

Definition of quality

An important issue to resolve is the definition of quality in health care (24,25). The Institute of Medicine has defined quality as "the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge" (26). Patients and practitioners sometimes offer competing definitions (24).

For the purposes of this paper, quality is defined along four axes: clinical outcomes, functional outcomes, patient satisfaction, and financial outcomes. All four dimensions are equally important, as described by the Clinical Value Compass developed by Nelson and associates (27).

Measurement

More than 30 years ago, Donabedian (28) conceptualized measurement of quality as focusing on three components: structure, process, and outcome. Structural measures examine credentials, rules, regulations, and accreditations. Process variables measure how providers accomplish their goals through prevention, screening, diagnosis, psychological and physical treatment, and rehabilitation. Outcomes measurement looks at short- and long-term results of the process interventions in the structural environment.

Quality can also be assessed by examining adherence to standards or by using scorecards. A discussion of the use of standards or treatment guidelines to measure and improve quality is beyond the scope of this paper. Besides the creation of guidelines, national efforts in the area of quality assessment have also focused on a search for a critical set of indicators for use in a scorecard that accurately and reliably measures the quality of care. Assuming that one of the primary objectives of a practitioner or organization is to meet patients' needs and expectations, quality indicators that reflect this objective and lead to the desired outcomes must be selected. A system cannot realistically track and use all the available indicators, nor is such a course useful or necessarily reflective of a chosen objective. In the final analysis, the selected indicators must allow for the evaluation of the system's or practitioner's ability to meet patients' needs and expectations (29,30).

The proper choice of indicators, especially the judicious choice of a few, is a major and daunting task. Organizations require very specific indicators that measure whether they achieve their objectives. The design of a quality measure, or indicator, is important to its effectiveness. Eddy (31) proposed five characteristics of a good indicator: purpose, target, dimension, type, and intended user.

Eddy also identified three potential purposes of an indicator—to determine the effect of an intervention on a group of individuals (outcome studies), to assess the impact of a change in a treatment or process, and to reveal differences in quality between two organizations such as hospitals or health plans.

The target—the entity being assessed, such as an outpatient clinic or the inpatient unit in a hospital—can also influence choices and design of indicators. All variables—for example, the insurance coverage or the support systems of the patient being treated—may not be under the control of a clinic or hospital. A measure must also identify the dimension being assessed, such as the extent of coverage of care or the extent of choices of providers.

The fourth characteristic of a good performance measure, or indicator, is the ability to reflect the different components, or variables, that led to a particular outcome. For example, medication-error rates reflect the quality of a nursing and pharmacy staff. On the other hand, rates of recovery from a depressive disorder reflect not only how good the pharmacy and nursing staff are but also the quality of the physicians, therapists, and any other aspect of the treatment process.

Quality indicators can be divided into six categories (32). Indicators related to patients' encounters with the system of care measure service quality, appropriateness of care, clinical outcomes, and functional status outcomes. Indicators that measure accessibility of care look at the system's capacity, the availability of clinicians, timely access, and geographic issues. The other four categories of indicators are prevention and screening, disease management, enrollee health status, and population health status. Ideally, the heath status of the population within the health care organization's service area reflects the long-term beneficial effect of the organization's preventive and acute-care interventions.

Finally, according to Eddy, it is important to identify the users of the performance measures. Patients, payers, employers, and policy makers have different needs and levels of sophistication. The performance indicators chosen must be of significant utility to these users to justify the cost of measuring these aspects of care.

To help in the task of choosing indicators and measuring performance, a solid and well-funded information system is critical (33). For systems that do not want to develop their own system of quality indicators and measurement tools, many are available for purchase.

Scorecards

In the past, quality indicators focused mainly on two aspects of care, clinical and financial. Clinically, the emphasis was, and still is in many instances, on perfecting the provider's performance so that errors and mistakes were reduced. The focus was on the outlier—the provider that fell outside of the norm—with little regard for the context or for adjustments for case mix and severity of illness. An organization's performance was measured against a standard set by a national organization such as the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, NCQA, and the Rehabilitation Accreditation Commission.

Financially, the quality measurement process reflected the performance of an independent entity, such as a psychiatric inpatient unit or an outpatient clinic, and used balance sheets and income statements.

Simply identifying, compiling, and tracking a set of indicators, however judiciously chosen, may not lead to desired objectives and may not result in a useful set of measurements. With the ever-expanding search to identify indicators of quality for health care in general (34), and of mental health services in particular (3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12), a fundamental question is raised: what will be the utility of indicators based on their purpose, acceptability, effectiveness, and impact? In other words, beyond identifying key characteristics and variables that indicate high-quality performance by a mental health system, how are they to be used effectively and toward what end?

A method to implement strategies for ensuring the provision of high-quality care is needed. An instrument is required to link the desired objectives to the indicators, at multiple levels and in a variety of areas. No method is currently available to understand how the choice of indicators influences the system of care and how the indicators measure the critical results.

Kaplan and Norton (35) have proposed the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) for business industries as a tool to implement a strategy as well as to measure its effectiveness. Use of the BSC requires the organization to identify and balance external measures of quality for customers and internal measures of the organization's critical delivery processes, innovation, and learning and growth. The BSC should combine measures of past performance with measures of what drives future performance.

Kaplan and Norton (35) consider four perspectives on quality, with corresponding indicators. Applied to behavioral health care, these perspectives are financial; customer, such as patient, family, payer, and employer; internal processes, such as clinical outcomes; and learning and growth, such as the capability and competency of individual clinicians, the adequacy of information systems, and the provider's ability to innovate. According to Kaplan and Norton, to be effective and yet manageable, a BSC must not exceed four or five indicators for each perspective, for a total of 20 to 25 indicators tracked closely.

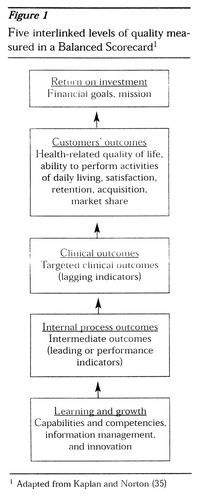

Each of the four sets or levels of indicators forms a chain of cause-and-effect relationships. For example, improvements in clinicians' skills, which are at the level of organizational learning and growth, result in higher-quality delivery of care, which is measured by intermediate or final clinical and functional outcome indicators. The result is a service provided to the patient, the patient's family, the payer, and the employer, who develop customer loyalty based on the perceived quality of the services and the product. Customer loyalty is measured by satisfaction, customer retention, and market share. Finally, customer loyalty is reflected in a desirable financial return, measured by financial indicators such as profit and loss.

The quality measures at each level must be understood as a function of the objectives at that level. Financial return indicators are a measure of the organization's financial objectives. However, understanding patients' objectives—their needs and expectations—may not be as easy as understanding financial objectives. Research on patient satisfaction, intuitively the measure closest to needs and expectations, has not yielded the expected information (34).

In this respect, it is important to distinguish between the quality of the service, which can be measured as the attentiveness of providers to patients' needs and expectations (for example, the quality of the "hotel" functions of a hospital) and the quality of the product—that is, whether the patient improved and was able to avoid death, disability, discomfort, and disease. The quality of such services as food, parking, and cleanliness are predominant in satisfaction surveys; however, patients do not equate the quality of these services with quality of care.

The notion of satisfaction is itself subject to interpretation. One can assert that an expectation has been met when a patient is satisfied, but what about need? Low-quality care may be acceptable to patients, while high-quality care may not. For example, a patient may be more satisfied when treated with an antidepressant medication rather than electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), even when the patient's profile clearly indicates ECT as the treatment of choice. Finally, being treated with respect and being permitted to maintain one's dignity, aspects of care that are not often addressed in satisfaction questionnaires, may be paramount in patients' definition of quality (24).

Clinical and functional outcomes can be understood by examining the difference between process measures, or what happened during the intervention, and outcome measures, or the patient's health-related quality of life before and after treatment. In the BSC, performance is measured by process indicators, also referred to as leading indicators. On the other hand, outcomes do not necessarily reflect performance but simply results. The latter are also referred to as lagging indicators. A patient's improvement, as measured by a lagging indicator, may occur as a result of or in spite of the process used by a clinician, which is measured by a leading indicator.

The challenge may lie in linking health-related quality of life to quality of care. In health care, several factors seem to be required for a link between a specific outcome and a particular process. It is important to identify a well-defined group of medical conditions or demographic characteristics, or both, and a well-accepted physiological, biochemical, or psychological mechanism linking the medical intervention with the outcomes targeted for the medical condition (24). For example, bipolar disorder can be considered a well-defined medical condition. The interventions that have been used to treat bipolar disorder have centered on several hypotheses. Currently, hypotheses that are based on the inhibition of neurotransmitters and neuroreceptor processes seem to have widely accepted support. Mood stabilizers, lithium, and anticonvulsants are the preferred medical interventions, reflecting the link between these hypotheses and medical outcomes.

To assess quality, it is necessary to use leading indicators, which are performance drivers such as relapse rate, side effects, and suicide rate, and lagging indicators, which are outcome measures such as recovery rates, functional levels, work productivity, and prevention of disease. Measuring performance drivers without measuring outcomes may prevent the assessment of an organization's or provider's success in the marketplace. One patient may not relapse to depression and another may stop making suicide attempts, but these outcomes do not indicate whether the patients were able to return to full employment and to the enjoyment of a fulfilling life. Knowing that a patient recovered from a psychotic episode tells us what happened, an outcome or lagging indicator, but not why or how it happened, a performance or leading indicator.

As developed for business organizations, the BSC was originally structured with four levels. However, I would propose adding a fifth level—clinical and financial outcomes—implicit in Kaplan and Norton's customer level (35), but useful as a separate and distinct category in health care. The four other levels are internal processes, clinical and financial outcomes, measures related to the customer, and financial measures.

• Learning and growth measures include professionals' competencies, capabilities, skills, and availability. They track the sophistication and accessibility of information systems and assess innovation initiatives.

• Internal process measures focus on intermediate functional, clinical, and financial outcomes such as length of stay, morbidity, complications, side effects, use of restraints, response time, and cost per unit of service.

• Examples of clinical and financial outcomes include recovery measures, mortality, and price per unit of service.

• Customer measures include those directly relevant to patients, families, payers, and employers. Examples are health-related quality of life, functional level, the ability to perform activities of daily living, satisfaction, and market retention, acquisition, and penetration.

• Financial measures include return on investment and economic value added (profitability or return on investment). In not-for-profit organizations, positive revenue over expenses is measured.

The cause-and-effect links between these five levels of indicators are represented in a sequential diagram in Figure 1.

Application of the BSC to behavioral health

In providing behavioral health care, clinicians and organizations are accountable for the value of the services delivered. To meet this responsibility, they must measure and report quality and financial outcomes. Behavioral health clinicians and administrators must manage their patients and the clinical environment so as to meet established objectives. The BSC is a tool to convey strategic intent by carefully choosing objectives and corresponding indicators and to report results. It adds to the panoply necessary to transform the current emphasis on managing cost to a more desirable objective of managing care.

How close are we to meeting the BSC standard of measurements and linkages in the area of mental health services? The efforts described in this paper, whether in health care in general or in mental health care in particular, are just a starting point and fall short of the types of measures and linkages needed for a BSC. We are still sifting through a collection of indicators and searching for a few measures of quality. We are still focusing on where the data are rather than where the data are needed. We analyze data that are collected rather than collecting the data that are needed. The current way that we choose, measure, and use quality indicators and establish links between them is less rigorous than the methods required to measure quality using the BSC.

In terms of measuring quality, health care information systems are still in an early stage. One reason is the relatively low funding levels for these systems in health care organizations. The ability of behavioral health care systems to measure quality is also in an early stage. Thus creating a technically perfect BSC, including a comprehensive set of indicators, may be unrealistic. It may be particularly unrealistic for health care organizations with several product lines, such as cardiovascular, oncological, behavioral, and obstetrical services. For an organization delivering a single product line such as behavioral health care, the task may be easier.

The BSC method requires the careful and realistic choice of no more than four or five indicators in each domain. Once a BSC is created, the links within the scorecard should allow for both assessment and prediction of the organization's performance. Each level must relate to the level above and below so that at the outset, a strategic objective from competency to financial viability is clear and logically developed, level by level.

If use of the quality indicators at any level does not obtain the expected results, then the causes for this failure should be able to be assessed from the results of the indicators at lower levels; the effects of the lower-level indicators on higher levels should be predictable. For example, a high readmission rate may be due to a shortage of trained staff, which may result in poor patient satisfaction, defection of payers, and a negative financial bottom line.

In one example of use of a BSC, a provider of mental health services would select the most important area to excel in, such as treatment of affective disorders, schizophrenia, or dementia. Second, the provider would identify quality indicators on each of the five BSC levels and ensure clear links between levels.

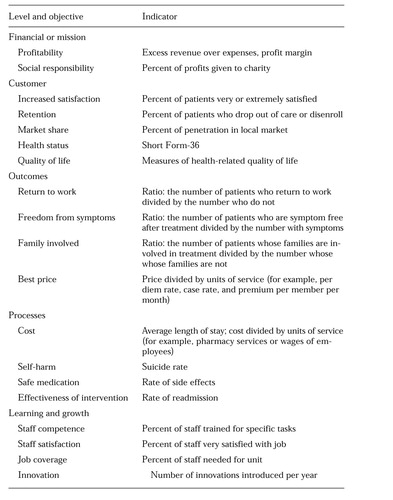

Table 1 lists objectives on five levels and related quality indicators. A typical BSC has two additional columns on the right, which are not shown on the table. One column is headed "Current, target, and benchmark." The current percentage of patients who are extremely or very satisfied may be 85 percent. The organizational target may be 95 percent, while the national benchmark may be 92 percent. The rightmost column is headed "action." It should contain brief descriptions of action plans undertaken by individual clinicians, teams of professionals, or the organization as a whole to achieve the objectives measured by the indicators. For example, the rate of medication errors in a psychiatric unit may be unacceptably high. The unit staff develop a plan to identify the sources of errors and to take corrective action to eliminate administration of medications that are not prescribed. By identifying specific objectives that are measured by each of these indicators with a specific benchmark, a set of action plans can be designed to guide the organization in a coordinated and integrated fashion. Any outcomes short of the target can be analyzed and modified based on an analysis of the preceding steps leading to the deficient outcome in the chain of events.

The scope of the measures in the BSC should be modest, achievable, and accessible and should reflect the highest priorities. The measures should also make sense to the user. Complex and unintelligible measures will be ignored or dismissed by scorecard users (29).

Finally, an objection might be that measuring outcomes requires a significant capital investment in personnel and in information systems. The latter is unquestionable; we can only manage what we measure, and both financial and technical difficulties abound in building useful information systems. The former, human resources, has been less of an issue in our efforts at developing a BSC for a health care network. Each product line—cardiovascular, orthopedics, rehabilitation, obstetrics, behavioral health, and so forth—developed their own BSC without incurring additional costs.

Upper and middle management should develop and use the BSC as the primary tool for implementing strategic planning and as a performance measurement instrument. Obtaining valid and useful information is a challenge. Developing profit-and-loss statements by product line is difficult but not impossible. Additional studies are needed to determine whether it is possible to implement the BSC without a major infusion of capital.

Conclusions

A BSC for behavioral health care can be useful for three reasons. First, its use may allow patients, employers, government agencies, and insurers to make informed decisions about the quality of the service delivered and the options available to purchase value (value is quality divided by cost). They will be able to request specific information about clinical outcomes, price, and satisfaction. Second, a BSC will permit organizations and practitioners to market their services by publishing their results, which permits informed patients, employers, and payers to make choices based on providers' capability and competency to meet their needs and expectations. Third, the BSC adapted to health care services from Kaplan and Norton's model (35) is a strategic planning implementation tool that combines sets of indicators, linking them in a chain of events and leading the organization in the desired direction. It also gives clinicians and administrators an effective tool to monitor their performance in the most important areas.

The current efforts in the field aimed at anticipating the need for health care quality measurements are commendable and impressive (36). They appear to concentrate on available measures and seem to be attempts to assess provider organizations cross-sectionally. However, these efforts may fall short of a method for integrating data fields. Use of a BSC can integrate indicators of quality in order to give rise to a plan of action. It may help reconcile the divided opinions on how to best achieve high-quality care. One school of thought proposes delivery of high-quality outcomes through internal efforts at continuous quality improvement (37). Another aims at developing scorecards that compel individual clinicians and large organizations to improve their results. The BSC can be used to satisfy both approaches in a synergetic fashion.

Our efforts to measure the quality of behavioral health care must be realistic and focus on the achievable, even to the detriment of the ideal. The number of indicators one can track is not important. Neither is it important to go only where data already exist or are easily accessible. It is better to concentrate on a modest attempt at measuring and linking data that leads to relief of patients' symptoms, pain, and disability and ultimately leads to a higher functioning level for patients.

Dr. Santiago is corporate medical officer at Carondelet Health Network, 1601 West St. Mary's Road, Tucson, Arizona 85745 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Five interlinked levels of quality measured in a Balanced Scorecard1

1 Adapted from Kaplan and Norton

|

Table 1. Quality objectives on five levels and related indicators that could be used in a Balanced Scorecard for behavioral health care

1. Kassirer JP: The quality of care and the quality of measuring it. New England Journal of Medicine 329:1263-1265, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Brook RH, McGlynn EA, Cleary PD: Quality of health care, part 2: measuring quality of care. New England Journal of Medicine 335:966-970, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Miller RH, Luft HS: Does managed care lead to better or worse quality of care? Health Affairs 16(5):7-25, 1997Google Scholar

4. White B: Restructuring mental health culture through client "commoditization." Psychiatric Services 48:1512-1514, 1997Link, Google Scholar

5. Mark H, Garet DE: Interpreting profiling data in behavioral health care for a continuous quality improvement cycle. Journal of Quality Improvement 23:521-528, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Dorwart RA: Outcomes management strategies in mental health: application and implications for clinical practice, in Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice. Edited by Sederer LI, Dickey B. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1996Google Scholar

7. Smith GR Jr, Manderscheid RW, Flynn LM, et al: Principles for assessment of patient outcomes in mental health care. Psychiatric Services 48:1033-1036, 1997Link, Google Scholar

8. Davis GE, Lowell WE, Davis GL: Measuring quality of care in a psychiatric hospital using artificial neural networks. American Journal of Medical Quality 12:33-43, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Commons M, McGuire TG, Riordan MH: Performance contracting for substance abuse treatment. Health Services Research 32:631-650, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

10. Buchanan JP, Dixon DR, Thyer BA: A preliminary evaluation of treatment outcomes at a veterans' hospital's inpatient psychiatry unit. Journal of Clinical Psychology 53:853-858, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Lanza ML, Binus GK, McMillian FJ: Quality plan for a product line. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 12(2):27-32, 1997Google Scholar

12. Shaw I: Assessing quality of health care services: lessons from mental health nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing 26:758-764, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Chassin MR: Assessing strategies for quality improvement. Health Affairs 16(3):151-161, 1997Google Scholar

14. Eddy DM: Balancing cost and quality in fee-for-service versus managed care. Health Affairs 16(3):162-173, 1997Google Scholar

15. Blumenthal D: Quality of health care, part 4: the origins of the quality of care debate. New England Journal of Medicine 335:1146-1149, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Morrissey J: Quality measures hit prime time. Modern Healthcare 27(18):66-76, 1997Google Scholar

17. Brailer DJ, Kim LH: From nicety to necessity: outcome measures come of age. Health Systems Review 29(5):20-23, 1996Google Scholar

18. Pauly MV, Brailer DJ, Kroch G, et al: Measuring hospital outcomes from a buyer's perspective. American Journal of Medical Quality 11:112-122, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Brailer DJ, Kroch E, Pauly MV, et al: Comorbidity-adjusted complication risk, a new outcome quality measure. Medical Care 34:490-505, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Brailer DJ, Kim LH, Paulus RA: Physician-led clinical performance improvement: quality management. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management 4:33-36, 1997Google Scholar

21. Brailer DJ: Report on the Wharton study group on clinical performance improvement. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management 4:37-43, 1997Google Scholar

22. Santa Fe Summit on Behavioral Health: Preserving Quality and Value in the Managed Care Equation, Final Report. Pittsburgh, American College of Mental Health Administration, 1997Google Scholar

23. National Committee for Quality Assurance: Health Employer Data Information Set (HEDIS 3.0). Washington, DC, National Committee for Quality Assurance, 1997Google Scholar

24. Cleary PD, Edgman-Levitan S: Health care quality: incorporating consumer perspectives. JAMA 278:1608-1612, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Blumenthal D: Quality of health care, part 1: quality of care—what is it? New England Journal of Medicine 335:891-894, 1996Google Scholar

26. Lohr KN (ed): Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1990Google Scholar

27. Nelson E, Mohr J, Batalden P, et al: Improving health care, part 1: the Clinical Value Compass. Journal of Quality Improvement 22:243-256, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Donabedian A: Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 44:166-206, 1966Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Hibbard JH, Jewett JJ: Will quality report cards help consumers? Health Affairs 16(3):218-228, 1997Google Scholar

30. Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL: What is accountability in health care? Annals of Internal Medicine 124:229-239, 1996Google Scholar

31. Eddy DM: Performance measurement problems and solutions. Health Affairs 17(4):7-25, 1998Google Scholar

32. Quality Measures: Next Generation of Outcomes Tracking: Implications for Health Plans and Systems, Vol 2. Washington, DC, Health Care Advisory Board, 1994Google Scholar

33. Brailer DJ, Goldfarb S, Horgan M, et al: Improving performance with clinical decision support. Journal of Quality Improvement 22:443-456, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Slovensky DJ, Fottler MD, Houser HW: Developing an outcomes report card for hospitals: a case study and implementation guidelines. Journal of Healthcare Management 43:15-34, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Kaplan RS, Norton DP: The Balanced Scorecard. Boston, Harvard Business School Press, 1996Google Scholar

36. Epstein AM: Rolling down the runway: the challenge ahead for quality report cards. JAMA 279:1691-1696, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Coaker M, Sharp J, Powell H, et al: Implementation of total quality management after reconfiguration of services on a general hospital unit. Psychiatric Services 48:231-236, 1997Link, Google Scholar