Unmet Need for Mental Health and Addictions Care in Urban Community Health Clinics: Frontline Provider Accounts

There are an estimated 890 community health clinics in the United States ( 1 ). These clinics deliver a disproportionate share of medical care to the uninsured, Medicaid enrollees, and vulnerable populations, many of whom are disadvantaged by low income, undereducation, racial-ethnic minority status, and language barriers ( 2 , 3 ). Consistent with the growing use of the medical care sector for treatment of mental and substance use disorders over the past decade ( 4 ), the burden of mental illness and addictions care in these clinics is substantial and often not accommodated by the parallel publicly funded mental health care system ( 5 ). Visits for mental illness and substance abuse in community health centers have tripled over the past five years ( 1 ), and systematic studies suggest that the rate of anxiety, depression, and substance abuse in these settings is in the range of 30%–40% ( 6 ). These figures are consistent with epidemiologic studies documenting an increased prevalence and persistence (that is, chronicity) of co-occurring mental and substance use disorders among patients who have low incomes and low education levels and who are members of racial and ethnic minority groups ( 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ).

Community health clinics face the daunting task of providing for these unmet needs in the absence of adequate funding and resources, creating significant frustration and tensions among clinic care providers and staff. Planning to improve care delivery for these unmet psychiatric needs in these clinics requires an in-depth understanding of the important social, cultural, and organizational factors that create the context for treatment delivery ( 11 , 12 ). One of the best ways to gather this important information is with qualitative interviews that elicit the viewpoint of frontline health care providers and other clinic personnel (collectively referred to here as "providers"). Such interviews can facilitate the identification of complex interactions and processes among patients, providers, and systems of care ( 13 ). The viewpoints of providers in community health centers rarely have been studied as a resource for program and policy development. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to capture this understudied and neglected perspective by describing frontline providers' attitudes, experiences, and concerns about the mental health and substance abuse problems of their patients, barriers to obtaining needed treatment, and proposed solutions to providing for this unmet need.

Methods

Participants

Purposive sampling was used to identify two community health centers in the urban core of Seattle with a rich mix of ethnic and racial diversity and socioeconomic disadvantage. We invited all providers at several of the centers' clinics, regardless of roles (for example, physician, nurse, or administrator), to participate in interviews so that we could account for various perspectives that contribute to clinic culture and health care context. The research was approved by the University of Washington's institutional review board (IRB).

Interviewees were recruited by distributing flyers that described the study to all clinic staff mailboxes and announcing the study at weekly staff meetings. Interested parties contacted the study interviewer to learn more and, if interested, to arrange their interview. After receiving a detailed description of the study, participants gave written informed consent before the interview. No one declined participation. A total of 17 study interviews were conducted, with two physicians, seven ancillary medical providers, five patient services staff, and three administrators. This sample covered a range of clinic roles. In agreement with the IRB, we did not seek in-depth demographic information from each participant.

Procedures

Interviews occurred between June 2003 and October 2004 and were conducted by a research assistant trained in semistructured interviewing techniques. Fourteen interviews were held in private clinic offices, one was held in the interviewee's home, and two interviews were done by telephone. For telephone interviews, the respondent was informed that privacy was guaranteed from the research assistant's secure telephone line but that they needed to take privacy precautions concerning their telephone connection and surroundings. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim with written consent from those interviewed.

The interviewer oriented the participant to the topics under investigation through the process of informed consent. Participants were told that we were interested in learning their thoughts about serving primary care patients with mental health needs in the clinic, about these patients' most significant needs, the barriers to meeting these needs, and strategies that may help overcome the referenced obstacles. The participants were informed that the interviewer would ask a few formal questions but that the tone of the interview would be similar to a conversation and that the direction the interview would take would be guided by the information shared.

During the interview, questions or discussion topics were used to ensure that key areas of interest were addressed. The direction of the interview could be controlled by the interviewees, who were encouraged to talk freely and expand, if desired, on each point made in response to the probe. Additional points that were raised were explored in a similar manner. Through this iterative process, all issues raised by the interviewees were touched upon several times by the interviewer in order to ensure comprehensive data collection. The interviews ranged from 45 to 90 minutes in length and were organized around six probe questions: "We are interested in your thoughts about patients you see in this setting who have psychiatric and substance use problems." "What concerns you most about working with patients with psychiatric problems in this setting?" "Given what you've said previously, what do you see as these patients' greatest needs?" "What do you see as the roadblocks or barriers that make it hard for patients to get their needs met?" "What do you see as the roadblocks or barriers for your clinic and its providers to provide for these needs?" "What do you think would help overcome these roadblocks and barriers?" Interviewees received $45 to compensate for their time without undue inducement to participate.

Data analysis

We used a descriptive, conventional content-analysis approach ( 14 , 15 ) and chose an inductive approach to derive the themes directly from the semistructured interview data as previously described ( 14 ). Content analysis allowed us to describe the research participants' accounts of their experiences as well as the contributions of their ideas to the broader social context issues that shaped their accounts as providers in a complex community health system. Descriptive content analysis is a useful approach when there is limited research on the phenomenon of interest ( 15 ). Two members of the research team independently coded major themes and subthemes from the raw verbatim interview texts. Both independently carefully read each interview several times line by line, extracting specific topics until both independently identified themes within and across interviews. These themes were then categorized by each coder into major and minor themes (or subthemes). Major themes were broad areas of interview text that were often voiced by the participants, with subthemes viewed as subsets of those broader areas.

Major and minor content areas were chosen inductively and semantically on the basis of the research purpose. Verbatim interview transcripts were read and reread in an iterative process to assess similarities and differences among the accounts. Preliminary themes were coded in accordance with an interview guide.

After they independently developed themes, both coders met for three hours and presented the major themes they had extracted from the interview texts. Coders then compared the specific passages of text they each had used to identify these common major themes to provide evidence for their thematic selections. Coders included major themes in the final analysis only if they collaboratively agreed on the precision of at least three or more examples of textual evidence. The reliance on textual evidence focused the discussion and minimized interpretive inconsistencies.

When disagreements about the inclusion of a major theme arose because of the textual evidence available, both coders presented the textual passage and their reasoning. The coders discussed the matter until they came to a consensus to include, discard, or rename the major content theme. Most disagreements were handled by renaming or reconceptualizing themes. Only one content theme had to be discarded. Having two coders who could agree with, refute, or expand the research interpretations promoted credibility of the analysis of these qualitative findings.

After major themes were established, the same procedure was followed to identify subthemes. Agreement about choice of broad theme and subordinate "subthemes" was reached by further discussion and consensus between the two raters. Because of the nature of the ongoing analytic discussions, a whiteboard was used along with poster paper and interview texts instead of a software package. In addition, digital photographs were taken to provide an electronic documentation of the changing and rewording of themes.

Results

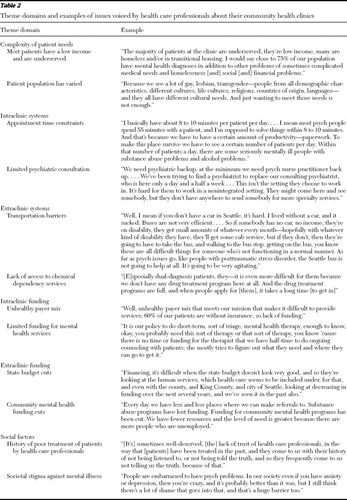

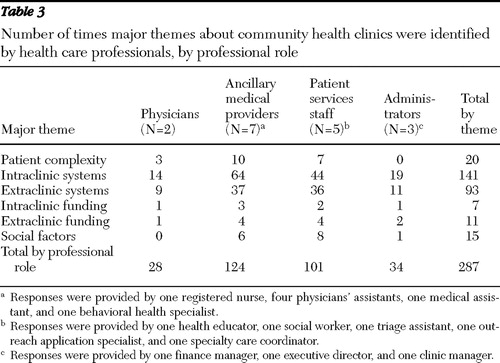

Demographic information for the clinics is provided in Table 1 . The final five major themes are presented below with textual examples of each in Table 2 and endorsements by specific groups of providers in Table 3 . [A table that lists the subthemes in order of their endorsement is available as an online supplement to this article at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

|

|

|

Complexity of patients' needs

Interviewees emphasized economic disadvantage and the exceptionally wide array of mental illnesses among their patients. They described mental illnesses that ranged from mild depression and anxiety to severe chronic mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, and noted that the extraordinary sociocultural diversity (a broad range of racial and ethnic diversity, religion, preferred language, and sexual orientation) created unique cultural health care needs for these patients.

Intraclinic systems

Interviewees mentioned three main systems issues with the clinics: the inadequate appointment time to deal with complex problems and the operational barriers to care within clinics, the absence of key professional supports (such as mental health case managers, regular psychiatric consultation, chemical dependency specialists and treatment, and language translators), and the need for a more expansive pharmacy formulary (because many patients cannot afford their medications) and services uniquely needed by many patients with mental illness. Services such as mailing medications to patients, visiting patients' homes, social work assistance, and expanded hours beyond the standard eight-hour work day were mentioned. Interviewees often viewed staffing patterns as insufficient to provide continuity of care with proactive seamless follow-up. They felt that variable staff expertise in cultural sensitivity and mental illness limited effective patient education, especially because opportunities for staff training to improve were not readily available. Finally, interviewees mentioned physical facility issues, such as archaic phone systems, overcrowded waiting rooms, and lack of offices for assessments and examinations.

Extraclinic systems

Interviewees most often mentioned problems patients faced in getting to medical appointments, such as navigating the public transportation system, which is the only transportation option for many clinic patients. They highlighted operational barriers to obtaining mental health care and substance abuse treatment outside the clinic, mentioning the lack of affordable mental health care and chemical dependency providers in the community, because many clinic patients do not have insurance and because of a dearth of dual-disorders programs to accommodate persons with co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders. Those interviewed felt that collaboration between clinics and outside agencies was poor, citing difficulty contacting providers in extramural mental health organizations, poor follow-up and communication when contact is made, and an erroneous assumption on the part of outside agencies that clinics have more capacity to deal with serious mental illness than they actually do.

Participants also noted a problem in relationships with pharmaceutical companies, pointing out that although the companies donate vital psychiatric medication to the clinics, they create problems by demanding excessive paperwork of clinic pharmacists, robbing them of time to perform their job duties, and often precipitously changing the charity formulary, which leaves patients vulnerable to losing access to needed medications.

Finally, they felt that the structure of the state mental health system itself created overwhelming barriers by requiring a year of persistent disability before qualifying for services, thereby requiring many Medicaid-eligible patients to have their mental health needs served by community health clinics. They noted that even when one's illness has become chronic, the challenging bureaucracy, paperwork, and waiting periods required to attain eligibility for services are overwhelming impediments to patients who have severe mental illness.

Intraclinic funding

Interviewees explained that the uneven insurance coverage, minimal coverage, or lack of coverage of patients made it difficult for clinics to budget for mental health services. They felt that these services tended to be devalued by payers in comparison with medical services. Participants also noted difficulties in recruiting and retaining mental health staff, because clinic providers are typically paid below-market salaries.

Extraclinic funding

Interviewees reported that the Washington State mental health system itself is extremely underfunded. Recent state budget cuts and shifts in funding were reported to increase the number of patients with mental illness without insurance coverage. They also mentioned lack of mental health parity as a factor that inhibits patients from getting adequate mental health care.

Social factors

Social issues mentioned by interview participants relate to the stigma of mental illness and poverty. A perceived judgmental attitude, lack of respect, and absence of listening and telling the truth to patients were thought to create a general mistrust of health care professionals. For example, they expressed a concern that some patients had developed a general mistrust of health care professionals because of past experiences with providers perceived as having a judgmental attitude, lack of respect, poor listening skills, and lack of truthfulness. In addition it was felt that persons with mental illness get negative feedback from society and frequently lose social standing and social support because of this, creating complications in the ability to receive sufficient mental health care.

Discarded theme

The only discarded theme involved benefits of providing mental health care in primary care settings. Only one coder thought this was a legitimate theme, and she identified only two endorsements by participants in the text of all 17 interviews.

Perspective by professional role

Table 3 shows the major themes that individuals endorsed according to their role in the clinic. Systems issues were by far the most frequently endorsed, dwarfing the other categories. Particular themes were not consistently associated with specific roles, although administrators with little direct patient contact understandably endorsed patient complexity and social factors themes less or not at all. The professional groups with more participants (that is, ancillary medical providers and patient services staff) contributed greater percentages of the total theme identifications than the smaller groups for every major theme. The number of theme identifications by each professional group tended to follow the same rank order as the total number of identifications across all groups in every case. The frequency with which different themes were identified by each professional group was similar to that in the overall group.

Discussion and conclusions

Because there is no current standardized approach for providing both mental health and substance abuse care in the community health clinic setting, the objective of this study was to identify the major content themes emerging from the understudied and neglected perspective of providers, in order to elucidate key contextual issues required for policy and program planning in this area.

Providers voiced several previously described systems barriers to adequate mental health treatment within the clinics, outside the clinics, and between the clinics and extramural providers ( 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ). In addition, participants cited unique patient characteristics in the community health center population that posed special difficulties for the adequate provision of effective treatment. This is consistent both with the overarching sociocultural context of these clinics and with findings from a previous study in publicly funded social and health service agencies describing complex challenges, such as competing demands, heavy caseloads, limited resources, and inadequate training ( 21 ). It does not appear that specific themes were differentially associated with clinic role, suggesting that the overall clinic context and patient characteristics were more powerful determinants of participant perspective.

Currently, the most widely studied and utilized approach to improve mental health care in primary care settings is the collaborative care model, which is closely patterned on the chronic disease model ( 22 ). In the collaborative care model ( 23 ), the patient's primary care provider is assisted by a care manager, usually a master's-level clinician (nurse or social worker, for example), working in consultation with a psychiatrist, who applies techniques to help patients manage their condition (patient education, psychotherapy, motivational enhancement, and approaches to identify and reduce treatment barriers) and assists in ongoing clinical monitoring of outcomes. Although these elements address some of the structural intraclinic systems issues voiced in this study, many other issues were raised in these interviews that neither the collaborative care model nor other models address.

Few collaborative care studies have focused on disadvantaged populations similar to those served by these clinics ( 24 , 25 ). These studies and other studies ( 26 , 27 ) have used special interventions designed to address sociocultural diversity and cultural health care needs identified in these interviews (specifically, the stigma of mental illness and poverty, manifested in the clinic as a perceived judgmental attitude and lack of respect for patients by providers). The studies found that this cultural "tailoring," along with special techniques designed to overcome the unique structural barriers to care faced by these patients (such as the transportation problems with the bus system mentioned by interviewees), benefited disadvantaged patients of racial and ethnic minority groups even more than white patients, probably because previous "usual care" received by patients from minority groups was of poorer quality ( 28 ). Although these studies suggest that this model might address other sociocultural issues, there are contextual issues, outlined below, that may not be easily addressed by the collaborative care model without considerable modifications.

Community health clinics often operate with an "unhealthy payer mix," whereby Medicaid covers most clients and other clients either have no insurance or low-paying private insurance. With most patients lacking insurance, the addition of clinic staff, such as care managers and psychiatrists, is economically unrealistic, particularly because, as interviewees pointed out, mental health treatment is devalued in comparison with general medical care. Even for those who have insurance, it is not clear how adding mental health providers in the form of care managers and consulting psychiatrists would affect insurance reimbursement in the absence of mental health parity. In addition, the lack of physical space in clinics to adequately meet treatment demand or expand services is something unique to this setting, as are problems with the continuity of psychiatric medications provided by pharmaceutical company charity programs. Finally, the heterogeneity of disorders with heavy comorbidity has not been addressed by any collaborative care programs thus far, which are mostly disorder specific. Although an ongoing program simultaneously addressing multiple anxiety disorders and depression is one step in this direction ( 29 ), many patients have additional problems with impulsivity, substance abuse, psychosis, bipolar illness, and personality disorder, creating clinical complexity that is quite daunting.

There are several study limitations. Limiting participation to interested individuals creates a bias. We did not link the demographic characteristics of the providers to the concerns they expressed. Thus it is difficult to determine whether provider background, classification, or years of experience influenced the information provided. This study was not designed for hypothesis testing, and the interview results are not as reproducible as results from standardized questionnaires. Also, we did not sample randomly as has been suggested by some qualitative experts ( 30 ) and studies ( 31 , 32 ), and so, given the small number of persons interviewed, we cannot be absolutely certain that our results accurately represent the context of community health care for mental illness. However, the results elucidate the challenges and contextual barriers to mental health care in this setting and were solicited directly from an untapped group—those closest to the quotidian process and systems, the frontline providers. This information can be used to more specifically investigate barriers and to begin to address real contextual barriers that any model of care delivery in this setting must incorporate if it is to be successful.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported in part by grant 1-K24-MH065324 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Dr. Roy-Byrne. The authors thank the staff and leadership from Country Doctor Community Health Clinics and Puget Sound Neighborhood Health Clinics who participated in these interviews and continue to provide high-quality care to their patients in the face of diminishing resources and increasing economic challenges.

Dr. Roy-Byrne has consulted for and served on the advisory board of Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Solvay. He has received honoraria as a continuing medical education speaker from Forest Laboratories, Inc. The other authors report no competing interests.

1. Druss BG, Bornemann T, Fry-Johnson YW, et al: Trends in mental health and substance abuse services at the nation's community health centers: 1998–2003. American Journal of Public Health 96:1779–1784, 2006Google Scholar

2. Institute of Medicine: America's Health Care Safety Net: Intact but Endangered. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2000Google Scholar

3. Meyer JA: Safety Net Hospitals: A Vital Resource for the US. Washington, DC, Economic and Social Research Institute, 2004Google Scholar

4. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629–640, 2005Google Scholar

5. Cunningham P, McKenzie K, Taylor E: The struggle to provide community-based care to low-income people with serious mental illnesses. Health Affairs 25:694–705, 2006Google Scholar

6. Olfson M, Shea S, Feder A, et al: Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders in an urban general medicine practice. Archives of Family Medicine 9:876–883, 2000Google Scholar

7. Breslau J, Kendler KS, Su M, et al: Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychological Medicine 35:317–327, 2005Google Scholar

8. Gilman SE: Review: there is marked socioeconomic inequality in persistent depression [comment]. Evidence-Based Mental Health 6:75, 2003Google Scholar

9. Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Kendler KS, et al: Specifying race-ethnic differences in risk for psychiatric disorder in a USA national sample. Psychological Medicine 36:57–68, 2006Google Scholar

10. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:617–627, 2005Google Scholar

11. Hohmann AA, Shear MK: Community-based intervention research: coping with the "noise" of real life in study design. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:201–207, 2002Google Scholar

12. Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC: Why don't we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. American Journal of Public Health 93:1261–1267, 2003Google Scholar

13. Miller CL, Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM: Using qualitative methods to distill the active ingredients of a multifaceted intervention. Psychiatric Services 54:568–571, 2003Google Scholar

14. Elo S, Kyngas H: The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing 62:107–115, 2008Google Scholar

15. Hsieh H, Shannon S: Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15:1277–1288, 2005Google Scholar

16. Schoenwald SK, Hoagwood K: Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: what matters when? Psychiatric Services 52:1190–1197, 2001Google Scholar

17. Goldman HH, Ganju V, Drake RE, et al: Policy implications for implementing evidence-based practices. Psychiatric Services 52:1591–1597, 2001Google Scholar

18. Hanson KW, Huskamp HA: State health care reform: behavioral health services under Medicaid managed care: the uncertain implications of state variation. Psychiatric Services 52:447–450, 2001Google Scholar

19. Pincus HA, Pechura C, Keyser D, et al: Depression in primary care: learning lessons in a national quality improvement program. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 33:2–15, 2006Google Scholar

20. Pincus HA, Pechura CM, Elinson L, et al: Depression in primary care: linking clinical and systems strategies. General Hospital Psychiatry 23:311–318, 2001Google Scholar

21. Munson M, Proctor E, Morrow-Howell N, et al: Case managers speak out: responding to depression in community long-term care. Psychiatric Services 58:1124–1127, 2007Google Scholar

22. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al: Rethinking practitioner roles in chronic illness: the specialist, primary care physician, and the practice nurse. General Hospital Psychiatry 23:138–144, 2001Google Scholar

23. Gilbody S, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, et al: Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care: a systematic review. JAMA 289:3145–3151, 2003Google Scholar

24. Miranda J, Schoenbaum M, Sherbourne C, et al: Effects of primary care depression treatment on minority patients' clinical status and employment. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:827–834, 2004Google Scholar

25. Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, et al: Improving care for minorities: can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities? Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Services Research 38:613–630, 2003Google Scholar

26. Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, et al: Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290:57–65, 2003Google Scholar

27. Miranda J, Azocar F, Organista K, et al: Treatment of depression among impoverished primary care patients from ethnic minority groups. Psychiatric Services 54:219–225, 2003Google Scholar

28. Miranda J, Bernal G, Lau A, et al: State of the science on psychosocial interventions for ethnic minorities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 1:113–142, 2005Google Scholar

29. Sullivan G, Craske MG, Sherbourne C, et al: Design of the Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management (CALM) study: innovations in collaborative care for anxiety disorders. General Hospital Psychiatry 29:379–387, 2007Google Scholar

30. Waitzkin H: On studying the discourse of medical encounters: a critique of quantitative and qualitative methods and a proposal for reasonable compromise. Medical Care 28:473–488, 1990Google Scholar

31. Zatzick DF, Kang SM, Hinton WL, et al: Posttraumatic concerns: a patient-centered approach to outcome assessment after traumatic physical injury. Medical Care 39:327–339, 2001Google Scholar

32. Zatzick DF, Russo J, Rajotte E, et al: Strengthening the patient-provider relationship in the aftermath of physical trauma through an understanding of the nature and severity of posttraumatic concerns. Psychiatry 70:260–273, 2007Google Scholar