Impact of the Medicare Modernization Act on Dually Eligible Persons With Psychiatric Diagnoses: A New York State Case Study

The Medicare Part D program of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 resulted in improved medication access and lowered out-of-pocket expenditures for millions of elderly persons without adequate drug coverage ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). Private prescription drug plans, or plans within Medicare managed care programs, provide coverage for Medicare enrollees in exchange for subsidized premiums and other payments from the federal government. Persons who are dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare are exempt from plans' monthly premium payments, annual deductibles, and the coverage gaps faced by other Part D beneficiaries. Dually eligible individuals had extensive financial protection against their prescription costs from Medicaid, but under the Medicare Modernization Act they must shift their medication coverage to Medicare. The jury is still out on the impact this has had on access to psychiatric drugs for dually eligible persons with psychiatric disorders. Definitive studies have been hampered by a lack of data on prescription drug use after the Medicare Modernization Act.

In New York State in 2002 there were nearly 530,000 dually eligible individuals, 210,000 of whom were disabled. Twenty-one percent of their total medication bill (nearly $800 million) covered antipsychotics, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants. Under Medicaid, dually eligible persons' copayments ranged from $.50 to $1.00 per prescription, and copayments were eliminated when in aggregate they exceeded $200. Most dually eligible persons in New York were (and still are) categorically excluded from Medicaid managed care demonstrations, especially for their mental health services, but before the Medicare Modernization Act they faced prescription drug limits (for example, limits of five to six refills per month and no more than 43 different medications over a year). Medicaid also required prior approval for brand-name medication if a generic existed, although a physician could override a negative decision. In 2002 virtually no prior approval request was denied for any medication for any Medicaid group ( 4 , 5 ). Under the Medicare Modernization Act, dually eligible persons' copayments increased to $1.00 to $3.00, depending on income and the tier classification of a medication, a more than doubling of that under Medicaid. If a consumer does not have the money for a copayment, pharmacists are not obligated to fill the prescription. If they do fill the prescription, they need to apply for tax credits for these unobligated amounts. The extent to which pharmacists will pursue this largesse is unknown.

Formularies must include at least two chemically distinct medications in each therapeutic class and, at the behest of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, they have included "all or substantially all" psychiatric medications, although generic versions are allowed. During the first year after the Medicare Modernization Act was implemented, plans were required to reimburse for previously written prescriptions ( 6 ). Nevertheless, there is a wide variation in offerings among the plans, so plan choice can matter to the dually eligible individual. Prescription drug plans develop their own formularies and set copayment tiers and drug restrictions. The selection of specific drugs by plans will in part depend on what they pay for medications to pharmaceutical drug companies. National for-profit corporations ran all but one of the 15 prescription drug plans offered in New York State, and 67% of plans developed their formularies by using in-house pharmacy benefit managers.

Dually eligible persons in prescription drug plans face problems. Generic medications have been shown to differ from brand-name drugs in efficacy and tolerability ( 7 , 8 , 9 ). Previously written prescriptions with refill limits eventually may not be filled by a particular prescription drug plan ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ). Higher copayments raise the concern of affordability for consumers. To mitigate these problems, federal legislation allows dually eligible individuals to change plans monthly. But information on which plan is optimal for a particular dually eligible person remains difficult to assess, and actuating a plan change may be challenging for many. In 2006 New York State offered a safety net for its dually eligible population, paying for all their noncovered psychiatric medications and requiring from consumers only the Medicaid copayment amounts.

States have costs additional to safety net costs. The Medicare Part D benefit for dually eligible persons is partially financed through the savings the federal government experiences from no longer having to remit to states a portion of the cost associated with the Medicaid medication provision. But the Medicare Modernization Act requires a phase-down state contribution ("claw-back" payment), designed to approximate the states' savings from the financing shift. For 2006 the claw-back payment from New York State was set at 90% of New York State's share of the 2002 average medication payment made on behalf of dually eligible persons. This contribution is to be reduced each year, capping at 75% by 2015 ( 14 ).

Several authors have forecasted negative consumer outcomes for the Medicare Modernization Act ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ). One group of authors, in a survey of a nationwide sample of psychiatrists, reported that more than one-half of psychiatrists' dually eligible clients had some type of service access issue and that one-third of these had some type of adverse clinical event ( 16 ). On the other hand, Donohue and Frank ( 17 ) reported that on average clients will fare well under the Medicare Modernization Act, with only a few experiencing significant problems accessing medications. Their simulation study combined data from a national Medicare beneficiary survey, formulary data from prescription drug plans, and data on usage behavior of Medicaid enrollees before the Medicare Modernization Act. Larger impact studies using other study approaches are still required to substantiate findings. There also are no studies on changes in costs to consumers and other payers. The simulation study presented here used a large Medicaid claims data set to examine access of dually eligible individuals with psychiatric disabilities to psychiatric and concomitant medications and consumers' and state's cost contributions before and after the implementation of the Medicare Modernization Act under the 2006 New York State Office of Mental Health's safety net policy. Costs for both the consumer and the state are considered jointly, because a redistribution of costs among these contributing payers can have an impact on consumer access.

Methods

In our study psychiatric drug claims for dually eligible persons under Medicaid in 2002 (the most recent available data set at the time of the study) were taken to represent drug usage under full access. How accessible these drugs were after the Medicare Modernization Act in the New York State prescription drug plans provided the basis of an access and costs analysis. Usage after the Medicare Modernization Act was simulated under random assignment of persons to plans, mimicking the initial enrollment procedure actually used in New York State, and under the best-fit enrollment scenario, which assumes a consumer with full knowledge chooses the plan providing the lowest "treatment gap" score (defined below), with respect to his or her full-access drug utilization profile.

Data sets

Data were from the personal summary and claims data from the New York State 2002 Medicaid Analytical Extract file. To ensure confidentiality and security, each unique MIS identification number was replaced with a randomly generated identification number that was used to identify clients for the study analyses. The study received expedited review approval from the Nathan Kline Institute Institutional Review Board.

The 15 prescription drug plans that offered New York State residents a standard benefit package on July 1, 2006, are included and described with data from public use files from the Formulary and Pharmacy Network Information ( 16 ). Data included each drug's tier placement and restrictions that include quantity limits, prior authorization, and step therapy.

Population

The study population was the 36,842 persons between the ages of 18 and 64 with at least one prescription claim in the Medicaid Analytical Extract data set, who had been disabled for the entire year (2002), and who had been identified as dually eligible beneficiaries with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, major depression, schizophrenia, or other psychoses, including delusional and paranoid disorders and other nonorganic psychosis. A person's diagnosis was taken from his or her inpatient claims, long-term-care claims, and outpatient claims. In cases of multiple diagnoses, the first diagnosis listed in the order of the following list was chosen: schizophrenia, bipolar, major depression, and other psychoses diagnoses.

A total of 719,139 medication claims were classified into four categories: drugs prescribed for psychosis, depression, or anxiety and concomitant drugs. The latter group represents the nonpsychiatric drugs that are frequently prescribed for psychiatric reasons or for common side effects and includes anticonvulsants, drugs for extrapyramidal or movement symptoms, sedatives or hypnotics, miscellaneous central nervous system medications, anorexiants or central nervous system stimulants, and lithium. If a drug was listed in more than one class, the first one among the classes was chosen in the following order: antipsychotics, antidepressants, antianxiety medications, and concomitant medications.

Outcome measures

Consumer medication access measures. Two measures were created. The "generosity" of a plan is a measure independent of actual consumer usage. It separately tallies the number of generic and brand-name drugs that are offered within tiers and weights these numbers by the number of restrictions placed on the drug. The number of restrictions was dichotomized into one or more than one. The scoring of the generosity measure is based on the following five premises. The more drugs covered, the more generous the plan. The more brand-name drugs covered, the more generous the plan. Placement of a drug in tier 1 (lower copayment) is more generous than placement in tier 2. Generosity is diminished by the number of restrictions placed on a drug. Having fewer restrictions on brand-name drugs is more generous than having fewer restrictions on generic drugs.

The generosity score was calculated for each drug class within a plan, and it was averaged over drug classes. Because the score has an arbitrary range, the score obtained under the restrictions of Medicaid was converted to a percentage. Possible scores range from 0% to 100%, with higher scores indicating greater generosity.

The treatment gap score measures how drug availability would change when consumers transfer from Medicaid to a prescription drug plan, assuming that they had received the same set of prescriptions. The score is a weighted sum of the percentage of all claims that could not be filled by a plan (that is, not filled as-is, with generic substitution, or with doctor's approval), the percentage of all claims requiring the doctor's approval for change in formulation, and the percentage of filled claims that were filled with generic substitutions and the percentage of filled claims that were filled with restrictions.

The scoring of the treatment gap measure makes the following three assumptions. First, not filling a drug prescription is worse than requiring a doctor's approval for the change of formulation. Second, filling a drug prescription requiring a doctor's approval is worse than filling a prescription with any restriction or with generic substitution. And third, for claims that were filled, filling with restrictions or generic substitution further increases the gap with lesser but equal consequence. The weights are chosen so that possible treatment gap scores range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating a greater treatment gap. [An appendix with more detailed information on the generosity score and treatment gap score is available as an online supplement at ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

Sensitivity analysis. Because both measures involve arbitrary weights, sensitivity analyses were performed. For the generosity score, the impact of weight variation on the ranking of plans was the main concern. When study-chosen weights were changed but remained in accordance with the underlying ordering premises of the weights, rank orderings of the generosity scores among plans virtually did not change, as indicated by rank order correlations of .99. Changes of the values of the measure remained within a narrow band.

For the treatment gap score the impact of weight variation on the difference in scores between random enrollment and the best-fit enrollment scenario was the concern. Weights used in the study placed a 1.5 times greater weight on categories related to filling prescriptions than on restrictions. We considered the extreme case in which the score would be based only on the proportion of prescriptions that could not be filled as-is, with generic substitution, or with doctor's approval—that is, placing a weight of 1.0 on unfilled prescriptions and .0 for all other categories. In this second case, both random enrollment and best-fit scores increased from study values. The difference in these scores from study weighted scores decreased by one-third, reflecting the fact that when a penalty is placed on restrictions, best-fit enrollment provides a greater gain. The score is thus sensitive to the weighting on restrictions. Input from stakeholders could lead to alternative weight choices.

Consumer costs. The consumer out-of-pocket cost measure is the sum of Medicaid copayments, copayments required under the safety net policy, and payments made for any residual medications not covered by a plan or by New York State. Consumer retail costs were estimated from New York State's medication reimbursement formula for Medicaid payments, average wholesale price, average manufacturers' price, and average retail price ( 18 ) expressed in 2002 dollars.

New York State costs. Because New York State shared 50% of Medicaid costs with the federal government ( 19 ), costs to New York State for the period before the Medicare Modernization Act were estimated as 50% of the amounts in the Medicaid Analytical Extract data file less consumer copayments. After the Medicare Modernization Act, Medicare assumes all medication costs for filled prescriptions for dually eligible beneficiaries. New York State estimated costs are then, under a full safety net for psychiatric medications, the sum of amounts paid by New York State to pharmacies on behalf of consumers for uncovered plan prescriptions covered by New York State's safety net plus New York State's claw-back payment to the federal government.

Study groups

Data analyses were conducted for the period before the Medicare Modernization Act, and the random and the best-fit enrollment scenarios were used for data in the period after the Medicare Modernization Act was implemented.

Analysis

A treatment gap score was calculated for the ith consumer in the jth plan. The average of these scores over consumers in a plan is the random allocation treatment gap score of the plan. For the best-fit enrollment scenario, a consumer was assigned to the plan for which his or her treatment gap score would be the lowest. The average treatment gap under best-fit enrollment for the plan is the average of the score over these assigned consumers. For each enrollment scenario, treatment gap score averages and univariate measures of the percentage of prescriptions covered as-is or with generic substitution, the percentage covered as-is (without generic substitution), and the percentage assigned to tier 1 status (low copayments) were calculated for the entire population and for each diagnostic group. Cost measures for enrollment scenarios were similarly created.

Because the data were composed of a total population (not a sample) and all 15 prescription drug plans available to consumers in 2006, study parameters are actual values and not estimates. Therefore, we report, without confidence limits, population means and standard deviations of the access and cost measures for the study groups.

Results

Sample description

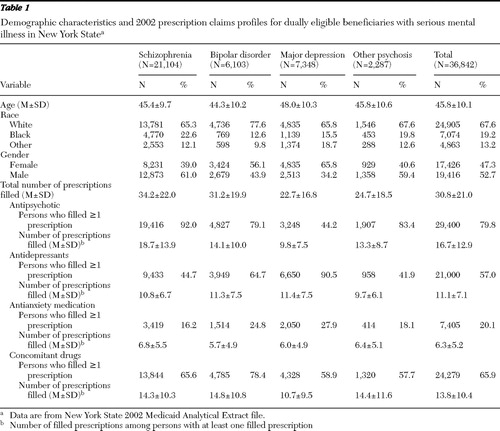

Table 1 displays the demographic characteristics and prescription drug profiles in total and by diagnostic groups for the 2002 Medicaid group under study. Schizophrenia was the most prevalent diagnosis (57%), followed by major depression (20%) and bipolar disorder (17%). Sixty-eight percent were white, and 47% were women. The average age was 46 years.

|

The mean±SD number of Medicaid prescription claims filled per person in 2002 was 30.8±21.0. People with schizophrenia had the largest number of prescriptions filled (mean of 34.2), and those with major depression had the fewest (mean of 22.7). Among persons with schizophrenia, nearly all (92%) had antipsychotic medication claims filled, nearly half (45%) had antidepressant claims, two-thirds (66%) had concomitant drug claims, and 16% had antianxiety medication claims. Among persons with bipolar disorder, nearly 80% had prescriptions filled for antipsychotic medications, nearly 80% for concomitant medications, 65% for antidepressants, and 25% for antianxiety medications. For those with major depression, 91% had antidepressant claims, 59% had concomitant medications claims, 44% had antipsychotic claims, and 28% had antianxiety claims.

Consumer medication access

Plans.Figure 1 depicts a stacked bar chart of the generosity scores for each medication class within all 15 prescription drug plans and also shows the overall average generosity score of each plan. Each segment of the stacked bar represents the generosity score for a medication category. Plans had the highest generosity scores with respect to antipsychotic medications and the lowest scores with respect to antianxiety medications. Plans that had higher generosity scores than other plans for a given medication class had higher generosity scores in almost all cases for all classes of drugs. Overall generosity scores for prescription drug plans ranged from 29% to 83% (mean=51%±19%). The total number of drugs offered over all classes ranged from 93 to 258 (mean=168±56). This compares to the 358 drugs found in the Medicaid claims data over all classes in 2002, or on average a 53% reduction.

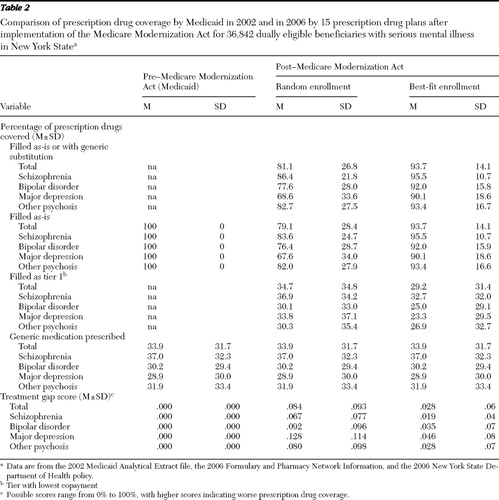

Consumers.Table 2 presents the access measures for the three enrollment scenarios, in total and by diagnostic group, for a one-year period under the prescription drug plans. Under the two Medicare Modernization Act enrollment scenarios (random and best-fit enrollment scenarios), persons with major depression had the highest treatment gap scores and those with schizophrenia had the lowest. For random enrollment, on average, plans covered for the year 81% of a person's psychiatric and concomitant prescriptions as written or with generic substitution. Only 2% of claims were filled with a generic substitution. Approximately 35% of claims were in tier 1. On average, persons with schizophrenia had the most complete coverage of claims, and those with major depression had the least complete coverage (86% versus 69%). The pattern is the same for the percentage of prescriptions filled as prescribed (84% versus 68%) and for the percentage of medications found in the lower-copayment tier 1 (37% versus 34%). Large standard deviations were noted and correspond to nonnormal peaked distributions with long tails.

|

Compared with random assignment, for the best-fit enrollment scenario, persons with major depression experienced the greatest improvement in the percentage of claims covered and those with schizophrenia experienced the smallest improvement (31% versus 11%). This was accompanied by a corresponding decrease in the proportion of medications in tier 1 for both types of disorders (31% versus 11%). treatment gap scores decreased for all groups by at least two-thirds.

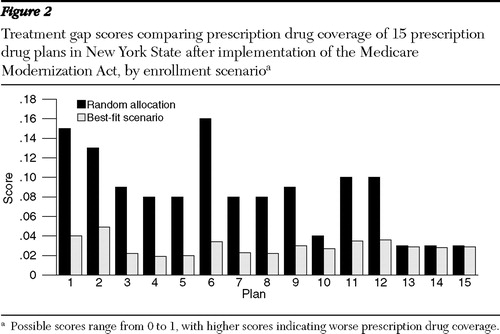

Figure 2 displays the treatment gap scores under random enrollment and the best-fit scenario. The treatment gap score under random enrollment varied from .03 to .16 (mean=.08±.04), and under the best-fit scenario it varied from .02 to .05, (mean=.03±.01). The correlation between the generosity measure and the treatment gap score under random enrollment was -.76, (p<.01), and under the best-fit scenario it was -.02 (not significant).

Costs

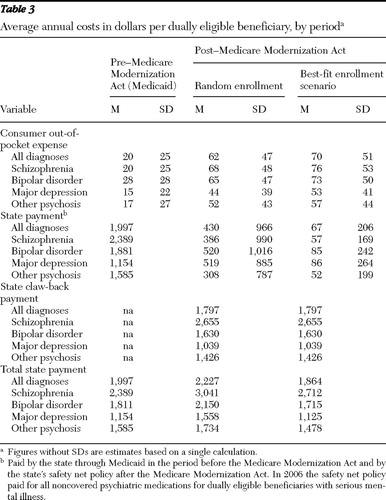

Table 3 displays average costs per year per dually eligible person for New York State and for consumers by enrollment scenario.

|

New York State costs. Under random enrollment, state costs increased by 12%, and under the best-fit scenario, state costs decreased by 7%, a 16.3% change. In the random enrollment scenario, the state's Medicaid authority experienced a savings of $1,567 per person per year, offset by the $1,797 claw-back payment. In the best-fit scenario, the claw-back payment was the same, but the state's Medicaid authority saved $1,930 per person per year, an 84% reduction in its safety net costs.

Consumer costs. To purchase the same bundle of medications in 2006 as in 2002 a dually eligible individual under the random-enrollment scenario would on average spend $62 annually out of pocket, more than a 210% cost increase. For persons with schizophrenia, the increase would be 240%, and for major depression, the increase would be 193%. Compared with random enrollment, under the best-fit enrollment scenario, there would be in total, over all diagnostic groups, a 250% increase in consumer costs.

Discussion

This study suggests that dually eligible beneficiaries with psychiatric disorders, particularly those with depression, would have experienced sizeable treatment gaps without New York State's generous safety net policy. Without it, on average only 81% of their medications would have been filled as-is or with a generic substitution. New York State's safety net policy ensured access at an estimated additional annual cost of only $3.5 million. If the state went one step further by adopting a best-fit enrollment policy, prescription coverage would increase 12.6%, and its safety net costs would be reduced substantially. This, however, would result in consumer copayments increasing from $42 to $62 per person, mostly because of the higher copayments required for brand-name prescriptions that became available under the prescription drug plans. For some consumers, these increases in copayments would be substantially larger. In the study data set, one person under random enrollment experienced an annual out-of-pocket cost of $960 (almost a fivefold increase over the Medicaid $200 stop-loss protection). Future studies should examine the extent to which these amounts in addition to increased out-of-pocket costs for nonpsychiatric medications may influence medication compliance and standard of living. Persons on Supplemental Security Income have incomes below the poverty line, and even small increases in their expenditures may be excessive.

Best-fit plan selection algorithms similar to those used in this study combined with ways to mitigate higher copayments could be developed, something that Donohue and Frank ( 17 ) commented might be beneficial. Generosity scores cannot be used alone, even though under random enrollment the generosity score and treatment gap score are highly correlated, because persons may still experience treatment gaps in generous plans depending on their particular treatment regimen. Although a Kaiser study ( 20 ) found that 10% of persons switched plans during 2006 and 2007, such an algorithm could provide incentives to consumers to switch between prescription drug plans as dictated by their medication demands. However, the feasibility of switching plans by using the algorithm, including decisions on when to switch, is problematic, particularly for this population. Furthermore, plans would have higher administrative costs as a result of switching plans. In addition, plans might vary highly in enrollment numbers. The simulation for best-fit enrollment resulted in six plans having less than 500 enrollees and three plans having more than 7,000. This uneven distribution of consumers would have marketplace implications, including the incentive for a reduction of the generosity of coverage of a plan.

Limitations of the study include the inability to incorporate consumer behavioral responses. Thus, for example, the extent to which a copayment increase might have provided incentives to reduce medication purchases by consumers was not modeled, and it may have resulted in an overestimate of consumers' out-of-pocket costs. Another limitation is that access to psychiatric medications was not considered in terms of access to all prescriptions. Furthermore, we had no way of incorporating a mechanism detecting possible corresponding increases in psychiatric and general-medical-related adverse events as predicted by West and colleagues ( 16 ) or in detecting changes in consumer health outcomes. The pre-post design, albeit a simulation, also failed to take into account temporal effects that could have an impact on patterns of use. The fact that this is a case study of New York also limits its generalizability. New York State is one of 37 states that have provided varying levels of temporary coverage during the transition to Part D to ensure dually eligible beneficiaries receive their prescription medications. New York State has a very generous safety net policy, so one might expect more extreme situations in other states and similar findings in states with equal generosity.

Finally, our work reports on the period soon after the implementation of the Medicare Modernization Act, a period characterized by great flux. From January 2006 to August 2006 New York State prescription drug plans changed the formularies of the psychiatric medications offered, some plans withdrew from participation, and plans from the same parent company that had at first offered distinct formularies switched to using the same formulary. Nationally, there has been some reduction in state claw-back obligations beyond those of the initial legislation. Also, starting January 2007 the New York State safety net contracted to include coverage of only second-generation antipsychotics, antidepressants, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines. Without further analysis, the net effect of these changes on out-of-pocket expenses or more medication disruptions is difficult to predict. The scene when things settle down needs to be studied. Further study could also include other medications and nonprescription claims.

Conclusions

This large state case study of the early impact of the Medicare Modernization Act on dually eligible persons with severe mental illness suggests that they, particularly those with major depressive illness, encountered a porous medication delivery system and experienced increases in out-of-pocket payments. Plans vary in their offerings, and consumers could benefit from selecting plans that minimize their treatment gaps. But the trade-off is that consumers will have higher copayments because plans that offer more options do so by adding brand-name drugs to the higher-copayment tier. State costs under best-fit enrollment are virtually budget neutral when compared with the period before the Medicare Modernization Act, and costs will be reduced further with reductions in claw-back payments. State contributions to help consumers offset higher copayments under best-fit enrollment might be a feasible option and further act to enhance consumer access.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by personal service contract 263-MI-60421, 2006–2007, from the National Institute of Mental Health. New York State Office of Mental Health provided partial salary support. The authors thank Eugene Laska, Ph.D., for invaluable input into the simulation design and selection of study measures. Joseph Wanderling, M.S., provided statistical input and support in the design of the generosity scores. Jerry Levine, M.D., Les Citrome, M.D., and William Greenberg, M.D., provided pharamacotherapy scenarios for initial tests of the methodology.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Catlin A, Cowan C, Hartman M, et al: National health spending in 2006: a year of change for prescription drugs. Health Affairs 27:14–39, 2008Google Scholar

2. Flemming C: Study Finds That Medicare's Drug Benefit Greatly Increases Seniors' Coverage: Some Continue to be Vulnerable to High Costs. Press Release, Health Affairs, 2007Google Scholar

3. Bach PB, McCllellan MB: A prescription for a modern Medicare program. New England Journal of Medicine 353:2733–2735, 2005Google Scholar

4. Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Fact Sheet, 2005. Menlo Park, Calif, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2006. Available at www.kff.org Google Scholar

5. State Medicaid Outpatient Prescription Drug Policies: Findings From a National Survey, 2005 Update. Menlo Park, Calif, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2005. Available at www.kff.org/medicaid/7381.cfm Google Scholar

6. Rules and Regulation. Federal Register 70: 4291, 2005Google Scholar

7. Kumet R, Gelenberg AJ: The effectiveness of generic agents in psychopharmacologic treatment. Essential Psychopharmacology 6:104–111, 2005Google Scholar

8. Nuss P, Taylor D, DeHert M, et al: The generic alternative in schizophrenia: opportunity or threat? CNS Drugs 18:769–775, 2004Google Scholar

9. Borgheini G: The bioequivalence and therapeutic efficacy of generic versus brand-name psychoactive drugs. Clinical Therapeutics 25:1578–1592, 2003Google Scholar

10. Morden NE, Garrison LP: Implications of Part D for mentally ill dual-eligibles: a challenge for Medicare. Health Affairs 25:491–500, 2006Google Scholar

11. Gellad WF, Huskamp HA, Phillips KA, et al: How the new Medicare drug benefit could affect vulnerable populations. Health Affairs 25:248–255, 2006Google Scholar

12. Elliott RA, Majumdar SR, Gillick MR, et al: Benefits and consequences for the poor and disabled. New England Journal of Medicine 353:2739–2741, 2005Google Scholar

13. Verdier JM, Kim M: Medicaid Drug Use Data Show High Cost and Wide Variation for Dual-Eligibles. Issue brief no 5. Princeton, NJ, Mathematica Policy Research Inc, 2005Google Scholar

14. Guyer J, Schneider A: Implications of the New Medicare Law for Dual-Eligibles: Ten Key Questions and Answers. Menlo Park, Calif, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2004Google Scholar

15. The New Medicare Prescription Drug Law: Issues for Dual-Eligibles With Disabilities and Serious Conditions. Menlo Park, Calif, Kaiser Family Foundation, June 2004. Available at www.kff.org Google Scholar

16. West JC, Wilk JE, Muszynski IL, et al: Medication access and continuity: the experiences of dual-eligible psychiatric patients during the first 4 months of the Medicare prescription drug benefit. American Journal of Psychiatry 165:789–796, 2007Google Scholar

17. Donohue J, Frank RG: Estimating Medicare Part D's impact on medication access among dually eligible beneficiaries with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 58: 1285–1291, 2007Google Scholar

18. Gencarelli DM: One Pill, Many Prices: Variation in Prescription Drug Prices in Selected Government Programs. Issue brief no 807. Washington, DC, National Health Policy Forum, 2005Google Scholar

19. Smith V, Gifford K, Kramer S, et al: The Transition of Dual-Eligibles to Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Coverage: State Actions During Implementation. Menlo Park, Calif, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, Feb 2006Google Scholar

20. Kaiser "spotlights" Medicare part D trends, 2006–2008. Psychiatric Services 59:124–125, 2008Google Scholar