Patient- and Facility-Level Factors Associated With Diffusion of a New Antipsychotic in the VA Health System

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: When new medications are introduced, a period of diffusion, evaluation, and adoption follows. This study evaluated the influence of patient- and facility-level characteristics on the early use of a new antipsychotic, ziprasidone, among Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) patients with schizophrenia. METHODS: Data on demographic characteristics, diagnoses, and outpatient pharmacy dispensings were obtained from the VA National Psychosis Registry for VA patients who received both a diagnosis of schizophrenia and oral antipsychotic medications during the fiscal years (FYs) 2001 (N=77,397), 2002 (N=74,724), and 2003 (N=74,399). Generalized estimating equations were used to examine associations between patient- and facility-level factors and ziprasidone use for each fiscal year. RESULTS: In FY2001, 1.2 percent of patients used ziprasidone. Ziprasidone use more than tripled to 4.0 percent by FY2002 and more than quadrupled to 5.9 percent by FY2003. In all study years, patients who were white, younger, and female were more likely to receive ziprasidone. Patients who had previous psychiatric hospitalizations or who had diabetes were also more likely to receive ziprasidone. Differences by race diminished over time. Facility academic affiliation and region were only minimally associated with use. CONCLUSIONS: Ziprasidone use increased rapidly among patients with schizophrenia after FDA approval, which suggests that both patients and providers remain eager to try new antipsychotic medications. Earlier dissemination was associated with clinical factors, such as comorbid diabetes, and with nonclinical factors, such as race or ethnicity. Differences by race diminished over time. The underlying processes and implications for affected patient groups are unclear.

When new health technologies are introduced, a period of evaluation and adoption follows (1). Adoption of a new technology depends on its acceptance by health care administrators, clinicians, and patients, who are likely to consider a number of factors, including the new treatments' effectiveness, risks, and costs compared with existing treatment options. Ideally, access to new treatments would be equitable, with risks and benefits being distributed fairly across patient groups (2,3).

The newer antidepressant and antipsychotic medications represent important but costly new technologies. When making decisions about prescribing these new agents, physicians are likely to consider a number of clinical factors (4). However, the use of new medications may also be influenced by nonclinical factors. Cross-sectional studies that have examined the adoption of the newer psychotropic agents several years after their introduction generally have shown that patients who are white and who are younger are more likely to receive these agents (5,6,7,8).

In 1997 Owen and associates (6) reported that among 599 patients who were discharged from Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) psychiatry units, white patients were more likely to receive second-generation antipsychotic agents than patients from other racial or ethnic groups (6). Between 1997 and 1999, Mark and colleagues (8) examined the use of antipsychotic medications among 752 patients and found that younger patients and those who were not African American had a greater likelihood of receiving second-generation antipsychotics. Using 1995 Medicaid claims data, Kuno and Rothbard (7) reported similar findings for a sample of 2,515 patients. Finally, Copeland and associates (9) examined antipsychotic use in 1999 among 69,787 VA patients with schizophrenia and found that African-American and Hispanic patients were slightly less likely than white patients to use the entire class of second-generation agents and were much less likely to use clozapine.

Fewer studies have examined the use of the newer antipsychotic medications over time. Using data from 5,032 patient visits in the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, Daumit and colleagues (10) reported that from 1992 to 1994, African-American and Hispanic patients with a variety of psychiatric diagnoses had odds ratios (ORs) of .50 and .43, respectively, for receipt of second-generation antipsychotics compared with whites. Although the ORs for receipt of new antipsychotic medications increased during subsequent time intervals (1995 to 1997 and 1998 to 2000), significant racial and ethnic differences remained (10).

Data such as these have led to a growing awareness and increasing concerns about potential racial or ethnic disparities in the use of newer medications. In this context, we examined whether a new antipsychotic medication is still used differentially across patient groups.

Ziprasidone, a second-generation antipsychotic agent, received approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of schizophrenia in February 2001. Ziprasidone was available to VA patients on a nonformulary basis until May 2002, when it was added to the VA's national formulary. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project panel endorsed ziprasidone as a first-line agent for schizophrenia in 2002, but VA strategic groups recommended that trials of risperidone or quetiapine be completed before trials of ziprasidone or olanzapine because of the latter drugs' greater costs (11,12).

At the time of ziprasidone's introduction, four other second-generation agents were available; three of these (olanzapine, risperidone, and quetiapine) were first-line agents. Ziprasidone appeared to be as effective as these agents in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia (11,13). However, ziprasidone did not appear to be uniquely effective among patients with treatment-refractory disorders. Although it appeared less likely to produce weight gain and metabolic changes than olanzapine and less likely to produce extrapyramidal symptoms than risperidone, there were early concerns about its potential for slowing cardiac conduction (11). However, after review, the FDA did not require special cardiac monitoring for patients receiving ziprasidone.

In the study reported here we examined the prevalence of ziprasidone use among VA patients with schizophrenia in the first years after this agent was introduced. We also examined whether patients' race or ethnicity and several other patient- and facility-level factors were associated with ziprasidone use. Finally, we evaluated whether the predictors of use changed over time.

Methods

The study was approved by the Ann Arbor VA's institutional review board. Data were obtained from the VA National Psychosis Registry (NPR), which is maintained by the Serious Mental Illness Treatment Research and Evaluation Center (SMITREC). The NPR includes data for all patients with diagnoses indicating psychotic disorders in VA inpatient settings from 1988 forward and in VA outpatient settings from 1997 forward. The NPR incorporates annual extracts from several VA administrative databases, including the VA National Patient Care Database and the VA Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) Strategic Healthcare Group database.

High levels of concordance have been reported between VA administrative data and medical record data in terms of patients' demographic characteristics, inpatient stays, and several diagnoses, including the diagnosis of schizophrenia at the time of inpatient discharge (14,15). PBM data are based on extracts of facility-level pharmacy data, which are part of the VA's electronic medical chart. Thus these data are sufficiently accurate to support daily clinical operations, such as medication ordering and dispensing. Measures of antipsychotic adherence, constructed from pharmacy data, are strongly associated with psychiatric hospitalization among patients with schizophrenia, which demonstrates the construct validity of these data (16).

Study population

We identified all patients who received a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and oral antipsychotic medications in each of the fiscal years during the observation period (N=77,397 in fiscal year [FY] 2001, N=74,724 in FY2002, and N=74,739 in FY2003). Over the three-year period, 104,082 individual patients met these criteria.

Measures

Demographic characteristics. Patients' race or ethnicity was categorized as African American, white, Hispanic, Asian or Native American, or unknown. Patients were also categorized by age group: younger than 45 years, 45 to 64 years, and older than 65 years; age was calculated at the midpoint of each fiscal year (April 1).

Antipsychotic use. Exposure to oral preparations of ziprasidone or other antipsychotics was determined by using national VA pharmacy data. Patients were considered to have received ziprasidone if they filled any prescription for this medication during the specified fiscal year, regardless of the duration of use.

Medical comorbidity. A modified version of the Charlson Co-morbidity Index was used as our measure of medical comorbidity. This index was based on the presence or absence of 19 medical conditions in administrative data in the previous fiscal year (17). Dummy variables were constructed for three categories of Charlson scores: 0; 1 or 2; and greater than 3. Patients were considered to have a comorbid diagnosis of diabetes if they had ICD-9 codes of 250 during the study year and were considered to have a concurrent cardiovascular diagnosis if they were assigned the ICD-9 codes of 391, 394-398, 402, 404-405, 410-413, 416, or 422-429 during the study year.

Illness severity. To measure the severity of preexisting psychiatric illness, we used a dichotomous indicator of whether patients had had a psychiatric hospitalization in the previous fiscal year.

Antipsychotic dosage. We categorized patients' antipsychotic medication dosages as being in the low, recommended, or high ranges on the basis of the dosages of patients' last antipsychotic prescription of the study year. We used dosage ranges suggested by the Texas Implementation of Medication Algorithms (TIMA) schizophrenia module (18). Ziprasidone dosages were considered to be in the recommended range if they were between 80 and 160 mg per day.

Facility-level variables. We assigned VA facilities to regions of the country (Eastern, Central, Southern, or Western) on the basis of a VA Health Services Research and Development regional designation (19). Facilities' levels of academic affiliation were based on information collected by the Association of American Medical Colleges as part of the 1999-2000 Annual Medical School Questionnaire of the association's liaison committee on medical education. A major affiliation indicated that the institution was a major site for clinical clerkships, a limited affiliation indicated that the institution offered only brief or unique rotations of students, and a graduate affiliation indicated that the institution offered only graduate training.

Data analyses

For each fiscal year, we described the cross-sectional prevalence of ziprasidone use for the entire sample and for important patient subgroups. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to examine multivariate relationships between the dependent variable, ziprasidone use, and patient- and facility-level factors, including age, race, sex, Charlson score, concurrent diabetes, concurrent cardiovascular condition, previous psychiatric hospitalization, facility region, and facility academic affiliation. In supplemental analyses, we included interaction terms for race and diabetes and race and psychiatric hospitalization in the model.

GEE methodology was introduced by Zeger and Liang (20) to properly estimate regression coefficients and variance when correlated data are used in the analyses. We used a GEE approach in this study because of the clustered nature of our data—patient observations were nested within VA facilities. All study analyses were completed with the use of SAS, version 8.02.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Reflecting the VA patient population, the 104,082 individual patients in the study were predominantly male (95 percent) and older (mean±SD age of 52.7±11.7 years). Approximately 53 percent were white, 28 percent were African American, and 11 percent were of unknown race. Twenty-two percent had a concurrent diagnosis of diabetes, and 17 percent had a concurrent cardiovascular diagnosis during one of the study years; 22 percent had had a psychiatric hospitalization in the year before their first study visit.

Ziprasidone use

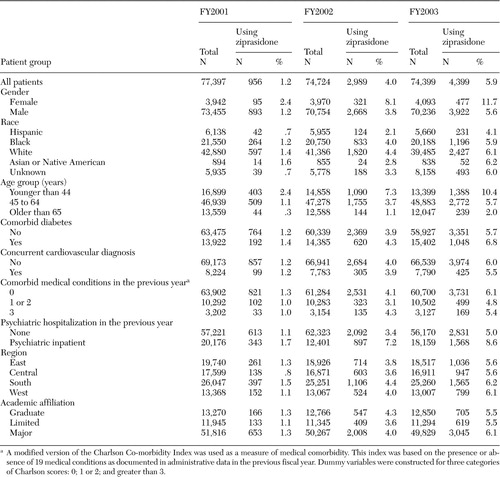

In FY2001, ziprasidone was received by 956 (1.2 percent) of the 77,397 veterans with schizophrenia who used oral antipsychotic medications. Ziprasidone use had tripled by FY2002, with 2,989 (4.0 percent) of 74,724 veterans receiving the medication, and it had more than quadrupled by FY2003, with 4,399 (5.9 percent) of 74,329 veterans receiving ziprasidone.

Despite its recent introduction, ziprasidone was as likely to be used at recommended dosages as other second-generation antipsychotics. In FY2001, dosages within the recommended range were prescribed for 70 percent of patients who received ziprasidone. These rates were comparable to the percentages of patients receiving recommended dosages of olanzapine (63 percent in FY2001) and risperidone (75 percent in FY2001).

Patient characteristics associated with ziprasidone use

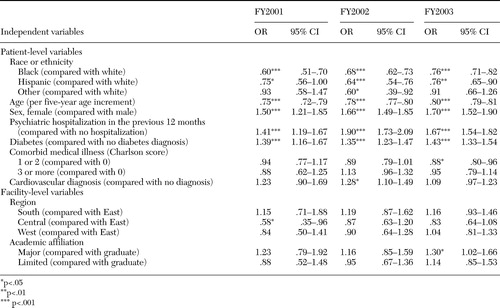

The frequencies of ziprasidone use by patient subgroup for each fiscal year are presented in Table 1. The ORs of ziprasidone use by patient subgroup for each fiscal year, adjusted for other patient and facility characteristics, are presented in Table 2. In each year (FY2001, FY2002, and FY2003), African-American and Hispanic patients were less likely to receive ziprasidone than were white patients. The OR for African Americans was lowest in FY2001, with higher ORs in each of the subsequent years (.60 in FY2001, .68 in FY2002, and .76 in FY2003).

Across study years, older patients were less likely to receive ziprasidone than were younger patients. In FY2001, for every five-year increase in age, the OR for patients' receipt of ziprasidone was .75 (95 percent CI=.72 to .79). Age-associated differences diminished only slightly in subsequent years. Women were more likely than men to receive ziprasidone in each of the study years, with these differences increasing over time. The OR for women receiving ziprasidone compared with men was 1.7 (95 percent CI=1.52 to 1.90) in FY2003. Patients who had a previous psychiatric hospitalization and patients with diabetes were also more likely to receive ziprasidone than other patients. Comorbid cardiovascular conditions were only minimally and inconsistently related to ziprasidone use. In analyses that treated individual patients who were seen between FY2001 and FY2003 as a cross-sectional sample, similar results were found.

In supplemental models of ziprasidone use that included interaction terms between race and diabetes and race and psychiatric hospitalization, we found significant associations only in FY2003. In FY2003, comorbid diabetes was associated with a greater increase in ziprasidone use among white patients than among Asian or Native-American patients (OR=2.4, CI=1.3 to 4.3). However, diabetes did not appear to differentially affect ziprasidone use among African-American or Hispanic patients compared with white patients. In FY2003, a previous psychiatric hospitalization was associated with a greater increase in ziprasidone use among whites than among African Americans (OR=1.2, CI=1.1 to 1.4).

Facility academic affiliation and geographic location did not have substantial or consistent associations with ziprasidone use.

Discussion

After ziprasidone was introduced, its use increased rapidly among VA patients with schizophrenia, more than quadrupling between FY2001 and FY2003 from 1.2 percent to 5.9 percent. Many patients with schizophrenia continue to experience symptoms despite treatment, and physicians and patients may be eager to try new antipsychotic medications.

In the first years after ziprasidone was introduced, its use was associated with several patient-level characteristics. Disparities in prescribing by some of these characteristics, such as patients' age, comorbid diabetes, and previous psychiatric hospitalization, may reflect physicians' considerations of clinical factors that affected the desirability of using ziprasidone or, more generally, the desirability of using a new agent. Differential prescribing by other factors, such as race or ethnicity, are less easily explained by such considerations.

Our finding of a lower rate of ziprasidone use among older patients is consistent with other studies that showed less use of new psychotropic agents among older patients (10). Studies that lead to FDA approvals often include limited numbers of older patients, and providers may delay prescribing new medications for older patients because of less certainty about dosing or because of greater concerns about side effects and safety.

Providers appeared to be more likely to prescribe ziprasidone to patients who had had a previous psychiatric hospitalization, perhaps because these patients had more severe psychiatric disorders or because many other treatment options had been tried. Providers were also more likely to prescribe ziprasidone to patients with diabetes, probably because of fewer concerns about weight gain with this medication than with several other antipsychotics. Surprisingly, given the early concerns about ziprasidone's effects on cardiac conduction, we did not observe different rates of prescribing for patients with a concurrent cardiovascular diagnosis.

Previous studies have had mixed findings with regard to gender and the use of newer medications (5,10). In this study, women were more likely to receive ziprasidone, perhaps because of greater concerns about weight gain or concerns about menstrual abnormalities or lactation. Ziprasidone is associated with less weight gain than olanzapine and produces less-sustained elevation in prolactin levels than risperidone (21,22). However, weight gain has important health implications for both men and women.

Our finding of racial and ethnic differences in the early use of ziprasidone is less easily explained by potential clinical considerations, although it is consistent with previous studies (8,10). There is little evidence that antipsychotics in general—or ziprasidone specifically—are less effective or more problematic among African-American or Hispanic persons with schizophrenia than among whites. Yet ziprasidone was prescribed less often for these groups. Coupled with earlier reports of disparities in prescribing of new psychotropic agents by race, this finding suggests that differential use may be a recurring pattern.

It is possible that patients' treatment preferences play a role in the differences in use of new psychotropic agents by race. In surveys, African-American patients are less likely to indicate that antidepressant treatment is an acceptable treatment option, and they may be less likely to accept antidepressant medications when these medications are recommended by their providers (21,23). Although limited data are available about the relative acceptability of antipsychotic medications, studies indicate that African-American patients are less adherent to antipsychotic regimens when they are prescribed, which suggests that such differences may exist (24).

Communication difficulties between patients and providers may also play a role in health care disparities and disparities in the use of new psychotropic agents. Communication difficulties are often exacerbated when the optimal treatment approach is uncertain (25,26). Racial and ethnic differences in ziprasidone use diminished over time in our study, possibly because physicians grew more experienced with using the medication and more certain about its potential risks and benefits, resulting in clearer recommendations to their patients.

Although our finding of disparities in the early use of a new antipsychotic medication raises concerns about unequal access to new medications, new medications can have unforeseen risks in addition to benefits. A recent study estimated that the probability of a new medication's being withdrawn from the market or acquiring a "black box" warning—one of the most stringent FDA cautions—was 20 percent over 25 years. Half these changes occurred within seven years of market introduction (27).

Important side effects have become apparent only after marketing for several newer psychotropic agents. The second-generation antipsychotics received new warnings of their potential to cause hyperglycemia and diabetes. Nefazodone, an antidepressant, acquired a black box warning because of its potential to cause liver failure; and all antidepressants recently received black box warnings because of their potential to increase suicidality among children and adolescents (28). Given the importance of postmarketing data and physicians' experience with new drugs, patient groups who experience short delays in receiving new agents may face more quantifiable risk-benefit ratios and, potentially, reduced risks.

Future studies are needed that explore decision making by physicians and patients about the use of new psychotropic agents.

One limitation of this study is the fact that we addressed the dissemination of just one new antipsychotic, focusing on "any use" of this medication. New medications may evidence a variety of dissemination patterns, particularly if they have advantages in terms of specific clinical symptoms or comorbid medical conditions—for example, diabetes. They also may be more or less likely to be used as adjunctive medications or included in complicated polypharmacy regimens. However, differential rates of use of or exposure to new psychotropic medications by sociodemographic groups has been a repeated finding in studies, even when there are no known differences in the potential effectiveness or liabilities of the new drugs among these groups.

This study was also conducted in only one health system, the VA. Patients from ethnic minority groups are more likely to seek mental health care in the VA (29), and VA pharmacy benefits are generous. These factors may contribute to less differential use of new agents by race or ethnicity in the VA than in other systems. However, it is also possible that the VA's early efforts to control ziprasidone use, first through nonformulary procedures and later through treatment recommendations, heightened the barriers already posed by different patient treatment preferences or by patient-provider communication difficulties.

Conclusions

Ziprasidone use increased rapidly among VA patients with schizophrenia after it was approved by the FDA. In the early diffusion period, white patients and younger patients were more likely to receive this medication than were patients who had previous psychiatric hospitalizations and diabetes. Exploratory results suggest that differences in medication use by race may diminish during the first years of availability, whereas differences by age may be more persistent. These findings raise concerns about the equitable distribution of new treatments. However, when other equally effective treatment options are available, patient groups who experience short delays in receiving new agents may face more quantifiable and, potentially, reduced risks.

Dr. Valenstein, Dr. McCarthy, Dr. Dalack, and Dr. Blow are affiliated with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Ann Arbor Center of Excellence, Serious Mental Illness Treatment, Research, and Evaluation Center (SMITREC) and with the department of psychiatry of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. Ms. Ignacio is with the SMITREC in Ann Arbor. Mr. Stavenger is with the VA VISN 11 headquarters in Ann Arbor. Send correspondence to Dr. Valenstein at SMITREC/VA Ann Arbor Center for Excellence, P.O. Box 130170, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48113-0170 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Use of ziprasidone by patients with schizophrenia being treated in the Department of Veterans Affairs, by fiscal year (FY) and patient group

|

Table 2. Odds of ziprasidone use, by patient- and facility-level characteristics, in multivariate generalized estimating equation (GEE) analyses

1. Rogers EM: Diffusion of Innovations. New York, Free Press, 1995Google Scholar

2. McKinlay JB: From promising report to standard procedure: seven stages in the career of a medical innovation. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 59:374–411,1981Crossref, Google Scholar

3. National Commission: The Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1979Google Scholar

4. Garrison GD, Levin GM: Factors affecting prescribing of the newer antidepressants. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 34:10–14,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Sclar DA, Robison LM, Skaer TL, et al: What factors influence the prescribing of antidepressant pharmacotherapy? An assessment of national office-based encounters. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 28:407–419,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Owen RR, Feng W, Thrush CR, et al: Variations in prescribing practices for novel antipsychotic medications among Veterans Affairs hospitals. Psychiatric Services 52:1523–1525,2001Link, Google Scholar

7. Kuno E, Rothbard AB: Racial disparities in antipsychotic prescription patterns for patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:567–572,2002Link, Google Scholar

8. Mark TL, Dirani R, Slade E, et al: Access to new medications to treat schizophrenia. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 29:15–29,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Valenstein M, et al: Racial disparity in the use of atypical antipsychotic medications among veterans. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1817–1822,2003Link, Google Scholar

10. Daumit GL, Crum RM, Guallar E, et al: Outpatient prescriptions for atypical antipsychotics for African Americans, Hispanics, and whites in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:121–128,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Miller AL, Hall CS, Buchanan RW, et al: The Texas Medication Algorithm Project antipsychotic algorithm for schizophrenia:2003 update. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65:500-508,2004Google Scholar

12. VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Strategic Healthcare Group: Recommendations for Atypical Antipsychotic Use in Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Disorders. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, June 2002, last updated May 2004Google Scholar

13. Schooler NR: Maintaining symptom control: review of ziprasidone long-term efficacy data. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64(suppl 19):26–32,2003Medline, Google Scholar

14. Kashner TM: Agreement between administrative files and written medical records: a case of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Medical Care 36:1324–1336,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Szeto HC, Coleman RK, Gholami P, et al: Accuracy of computerized outpatient diagnoses in a Veterans Affairs general medicine clinic. American Journal of Managed Care 8:37–43,2002Medline, Google Scholar

16. Valenstein M, Copeland LA, Blow FC, et al: Pharmacy data identify poorly adherent patients with schizophrenia at increased risk for admission. Medical Care 40:630–639,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al: A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Disease 40:373–383,1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Miller AL: TIMA Procedural Manual: Schizophrenia Module, 2003Google Scholar

19. United States, by Region: Eastern, Central, Southern, Western. Washington, DC, Veterans Health Services and Research Administration, 1991Google Scholar

20. Zeger SL, Liang KY: Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics 42:121–130,1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Bobes J, Rejas J, Garcia-Garcia M, et al: Weight gain in patients with schizophrenia treated with risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, or haloperidol: results of the EIRE study. Schizophrenia Research 62:77–88,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Homel P, Casey D, Allison DB: Changes in body mass index for individuals with and without schizophrenia, 1987-1996. Schizophrenia Research 55:277–284,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al: The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Medical Care 41:479–489,2003Medline, Google Scholar

24. Valenstein M, Blow FC, Copeland L, et al: Poor adherence with antipsychotic medication among patients with schizophrenia: patient and medication factors. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:255–264,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Ashton CM, Haidet P, Paterniti DA, et al: Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of health services: bias, preferences, or poor communication? Journal of General Internal Medicine 18:146–152,2003Google Scholar

26. Balsa AI, Seiler N, McGuire TG, et al: Clinical uncertainty and healthcare disparities. American Journal of Law and Medicine 29:203–219,2003Medline, Google Scholar

27. Lasser KE, Allen PD, Woolhandler SJ, et al: Timing of new black box warnings and withdrawals for prescription medications. JAMA 287:2215–2220,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. MedWatch: The FDA Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program, 2004. Washington, DC, US Food and Drug Administration, 2004Google Scholar

29. Rosenheck R, Fontana A: Utilization of mental health services by minority veterans of the Vietnam era. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:685–691,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar