Rearrest and Linkage to Mental Health Services Among Clients of the Clark County Mental Health Court Program

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined rearrest and linkage to mental health services among 368 misdemeanants with severe and persistent mental illness who were served by the Clark County Mental Health Court (MHC). This court, established in April 2000, is based on the concepts of therapeutic jurisprudence. This study addressed the following questions about the effectiveness of the Clark County MHC: Did MHC clients receive more comprehensive mental health services? Did the MHC successfully reduce recidivism? Were there any client or program characteristics associated with recidivism? METHODS: A secondary analysis of use of mental health services and jail data for the MHC clients enrolled from April 2000 through April 2003 was conducted. The authors used a 12-month pre-post comparison design to determine whether MHC participants experienced reduced rearrest rates for new offenses, reduced probation violations, and increased mental health services 12 months postenrollment in the MHC compared with 12 months preenrollment. RESULTS: The overall crime rate for MHC participants was reduced 4.0 times one year postenrollment in the MHC compared with one year preenrollment. One year postenrollment, 54 percent of participants had no arrests, and probation violations were reduced by 62 percent. The most significant factor in determining the success of MHC participants was graduation status from the MHC, with graduates 3.7 times less likely to reoffend compared with nongraduates. CONCLUSIONS: The Clark County MHC successfully reduced rearrest rates for new criminal offenses and probation violations and provided the mental health support services to stabilize mental health consumers in the community.

After the creation of the first mental health court (MHC) in Broward County, Florida, in 1997, numerous mental health courts have sprung up across the nation. Although there is hope that MHCs meet the mental health treatment needs of clients while simultaneously reducing their involvement with the criminal justice system (1), empirical reports on the outcomes of MHCs are lacking (2).

A recently published evaluation of the Broward County MHC (3) addressed use of mental health services. The authors found that use of behavioral health services by misdemeanants in the MHC was increased significantly, whereas the likelihood of using services among defendants in a comparison court was virtually unchanged. Although the Broward County study found that the MHC enhances treatment access and involvement for its clients, it did not address whether MHC clients had lower involvement with the criminal justice system.

Preliminary findings of the MHC in King County indicated that MHC clients had decreased recidivism rates after participation in the MHC compared with before (4). For the Seattle MHC, the duration of the jail stay decreased after participation in the MHC, compared with increased duration for clients who opted out of the MHC. The results of that study suggest that the MHC was successful in reducing the recidivism rate of participants. However, the study did not empirically address whether MHC clients received more mental health services.

The goal of the study reported here was to address both the question of recidivism and mental health service linkage for the Clark County MHC. Specifically, the study addressed the following questions about the effectiveness of the MHC: Did MHC clients receive more comprehensive mental health services 12 months postenrollment in the MHC compared with 12 months preenrollment? Was recidivism reduced for MHC participants 12 months postenrollment compared with 12 months preenrollment? Were any client or program characteristics associated with recidivism?

To address these questions, a secondary analysis of use of mental health services and jail data for all MHC clients who were enrolled in the program since its inception in April 2000 through April 2003 was conducted. We used a 12-month pre-post comparison design to determine whether MHC participants experienced reduced rearrest rates for new offenses 12 months postenrollment in the MHC compared with 12 months preenrollment. We also examined whether MHC clients experienced fewer rearrests for probation violations postenrollment.

Methods

The Clark County Mental Health Court

The MHC in Clark County has been in operation since April 2000. In October 2001, a grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration funded a comprehensive study of the MHC program. The Clark County MHC shares a number of common attributes with other MHCs around the country as cited by Goldkamp and Irons-Gyunn (1): Participation in the MHC is voluntary. There is a requirement that the defendant consent to participation. Screening and referral of defendants are completed within the first 24 hours after arrest to expedite release from jail and link to appropriate treatment. The MHC operates as a problem-solving court under the philosophy of therapeutic jurisprudence. All MHC cases are handled on a single court docket in which clients appear at regularly scheduled hearings before the MHC judge. Finally, all cases are judicially supervised to ensure compliance with structured community-based mental health treatment. A detailed description of the specific operational procedures of the Clark County MHC has been provided by Judge Randal Fritzler, the presiding judge over the MHC in Vancouver, Washington (5).

Participants

The Clark County MHC enrolled 368 mentally ill offenders between April 2000 and April 2003. The sampling frame consisted of all misdemeanants arrested and residing in Clark County, Washington. Those who met the following eligibility criteria were enrolled in the MHC: were 18 years of age or older; had been charged with a misdemeanor or a gross misdemeanor (or a felony charge that was successfully pled down to a misdemeanor); had a DSM-IV axis I diagnosis of major mental illness (schizophrenia, major affective disorder, or other diagnoses with psychotic symptoms); were able and willing to make a voluntary choice to have the case disposed in the Clark County MHC; did not have a developmental disability (for example, an IQ below 70); and did not have only an axis II personality disorder. All study procedures were approved by Portland State University's human subjects research review board.

Enrollment procedures

Mentally ill offenders entered the MHC either through a jail triage process or through a referral from the criminal justice system. In both cases, three Clark County MHC coordinators were responsible for verifying the eligibility of potential clients on the basis of the criteria detailed above. The MHC coordinators were master's-level qualified mental health professionals who had been trained to conduct mental health and drug and alcohol assessments. After the MHC assessment, MHC coordinators provided a description of the MHC program to eligible offenders and explained the post-plea nature of the court (clients must plead guilty to their charges, which are expunged upon graduation from the MHC). The MHC was initially offered on a pre-plea basis (clients could enroll in the MHC in lieu of sentencing). The program became a post-plea program in October 2001.

The client was then left to make his or her decision about enrollment before being arraigned. After enrollment, each client was referred to appropriate mental health services by his or her court coordinator, usually within 24 hours. Both the court coordinators and mental health service providers supervised clients on an ongoing basis throughout their participation in the MHC program.

Data collection

Arrest data. Booking data were provided by the Clark County Department of Community Services and Corrections for all individuals enrolled in the MHC. The corrections management information system (MIS) tracks all charges brought against an offender on the date that he or she is booked, the court case number, and the status of the offense. From these data, the number of arrests, the type of crime, the class of crime (felony versus misdemeanor), and probation variables were created.

Mental health service utilization data. Mental health services data were provided by the Clark County Regional Services Network (RSN) for all MHC clients. Variables included DSM-IV diagnosis, drug and alcohol assessment information, and mental health service use. Service use data were tracked by the RSN through daily activity logs in which service providers recorded the type of service activity, units (in 15-minute increments), and location of services provided for all clients each workday. The type of activities tracked included assessment, case management, medication management, crisis-related services, intake, employment, other outpatient services, inpatient services, and day step-down diversion from the hospital. RSN data were acquired for all MHC clients for 12 months before enrollment in the MHC and 12 months postenrollment.

For clients to be included in this study, at least 365 days since enrollment in the MHC must have accrued, so that recidivism could be measured for each participant 365 days postenrollment in the MHC compared with 365 days preenrollment. Of the 368 clients who participated in this study, 69 had successfully graduated, 222 had terminated from the project without graduation, and 77 were still enrolled in the MHC program. However, all 368 had at least 365 days past initial enrollment in the MHC. Of the 222 terminated clients, 116 (32 percent) were terminated from the MHC for noncompliance with requirements, 75 (20 percent) opted out of the program, 24 (7 percent) were transferred to another court (either a substance abuse court or a domestic violence court) because of the prevalence of domestic violence or substance abuse issues, and seven (2 percent) moved out of the district. The average number of days enrolled in the MHC for the 222 terminated clients was 161, compared with 382 days for the graduates. For the 77 enrolled clients, the average number of days in the program was 409. All clients had 365 "follow-up" days postenrollment.

Data analysis. For the purpose of our analysis, variables were conceptualized in terms of five blocks: demographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, use of mental health services, criminal history, and MHC participation. The demographic variables were age, gender, and ethnicity (white versus not white). Clinical characteristics were dummy coded into diagnosis of schizophrenia or affective disorders and were compared with other mental health disorders. Previous psychiatric inpatient treatment and alcohol or drug treatment were used as dichotomous variables. Mental health service use variables were hours of mental health service use in the 12 months before enrollment in the MHC and in the first 12 months postenrollment. Criminal history variables were the number of times booked one year preenrollment in the MHC and the highest class of crime (misdemeanor or felony) for any arrest in the past 12 months.

One-sample t tests were used to examine changes in the number of arrests and hours of mental health services used 12 months preenrollment in the MHC and 12 months postenrollment. Multivariate prediction models were fitted by using logistic regression to examine predictors of rearrest for new offenses at 12 months. Effect size was assessed with odds ratios. Statistical significance of the affect was assessed with the Wald chi square statistic. SAS was used for the statistical analyses.

Results

Sample description

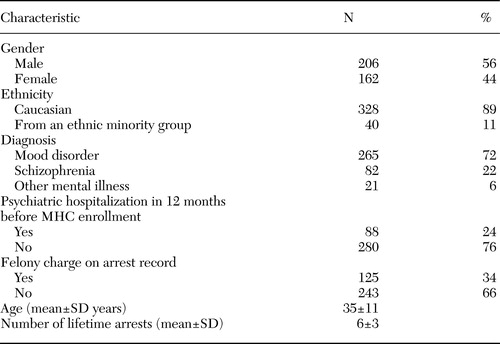

This sample of 368 MHC clients had slightly more men (56 percent) than women (44 percent). A majority of clients were Caucasian (89 percent), compared with 11 percent from ethnic minority groups. The average age of the sample was 35.1 years (range, 18 to 61). Most clients had a mood disorder (72 percent), followed by schizophrenia (23 percent) or other axis I mental illness (6 percent). On average, individuals had 6.3 previous lifetime bookings, and almost one-quarter had received inpatient psychiatric care in the past 12 months (Table 1).

Linkage to mental health services

Newly enrolled MHC clients were linked to mental health services within three to ten days of enrollment. The assigned mental health care provider appeared with the newly enrolled client before the judge either at the time of arraignment (which occurred on the day after the arrest) or on the next court date, which was scheduled within one week after arraignment.

Mental health service use data were recorded in the Clark County RSN for 320 MHC participants served from April 2000 through June 2003. It is unclear why data for 48 MHC participants were missing from the administrative database.

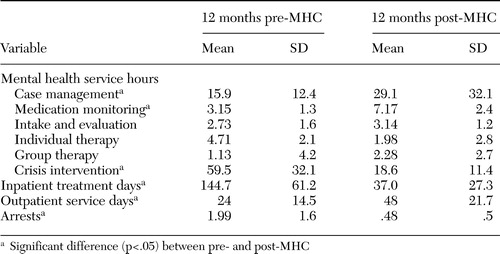

Seven categories of services were compared for MHC clients 12 months preenrollment in the MHC and 12 months postenrollment and are presented in Table 2. MHC clients received more hours of case management and medication management and more days of outpatient service after enrollment. MHC clients also received fewer hours of crisis services and fewer days of inpatient treatment after enrollment in the MHC.

Rearrest

Next we addressed whether MHC participants had fewer arrests on new charges 12 months postenrollment compared with the 12 months preenrollment. In the 12 months preenrollment, these 368 mentally ill offenders were arrested a total of 713 times. Preenrollment, approximately one-quarter of the sample (26 percent) could be characterized as "frequent offenders," with at least three arrests in the 12 months before enrollment. In the 12 months postenrollment, 199 participants (54 percent) had no arrests. The remaining 169 participants were rearrested on new charges and booked a total of 178 times. Postenrollment only 2.8 percent were "frequent offenders" with at least three arrests. The average number of arrests for all participants was significantly reduced from 1.99 preenrollment to .48 postenrollment (paired t test=17.73, df=367, p<.001).

Probation violations

In the 12 months before enrollment in the MHC, 46 percent of the MHC participants had at least one probation violation. These 169 offenders committed a total of 194 probation violations before enrollment. In the 12 months postenrollment, there was a significant 62 percent reduction in the number of probation violations, with 68 participants committing 74 violations.

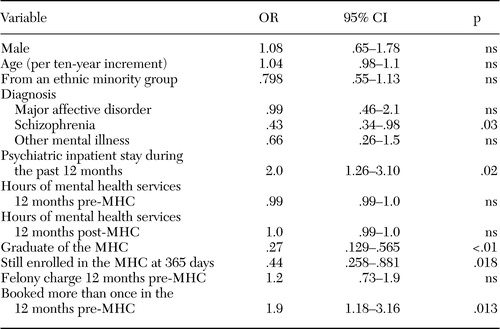

Finally, we tested a multivariate model of predictors of arrest status for new crimes postenrollment. As shown in Table 3, logistic regression analysis found that participants who graduated from the MHC were 3.7 times less likely to be rearrested compared with those who were terminated from the MHC for other reasons (odds ratio=.27). In addition, those who were still enrolled after the 365-day observation window were 2.3 times less likely to be rearrested than those who terminated (odds ratio=.44). MHC participants who were hospitalized in a psychiatric facility in the previous 12 months were almost twice as likely to be rearrested. Participants who had been booked more than once in the previous 12 months were also significantly more likely to be rearrested. However, those with schizophrenia were half as likely to be rearrested compared with those with other diagnoses. Factors found not significant as predictors of rearrest included being male or from an ethnic minority group, age, hours of mental health service use, and prior felony charge.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that the MHC helps break the cycle of the repeat offender. The overall crime rate for MHC participants was reduced 400 percent one year after enrollment in the MHC compared with one year before. In addition, MHC participation was associated with a 62 percent reduction in rearrest for probation violations.

The most significant factor in determining the success of MHC participants was graduation status. MHC clients who did not graduate were 3.7 times as likely to reoffend compared with those who did graduate. It is noteworthy that the link between graduation status and rearrest remained significant after we controlled for diagnosis, prior arrest history, mental health treatment, and clients' demographic characteristics and suggests that MHC participation significantly affects the rearrest behavior of mentally ill offenders.

However, an unexpected finding was that increased intensity of mental health services measured by hours of service was not significantly associated with rearrest. A limitation of this study is that we did not have measures of key qualitative aspects of the court. However, exploratory qualitative data were collected from a subsample of 55 consumers that suggested that relationships developed between the MHC coordinator, the judge, and the consumer were critical to clients' success. In addition, at the system level, the MHC represents extensive interagency service coordination between the mental health, adult corrections, and the local consumer advocacy agency. With this cooperation, the agencies were able to reach a common consensus of how therapeutic jurisprudence would best serve mentally ill offenders in Clark County. It is likely that these qualitative aspects of the MHC contributed to reduced rearrest among MHC clients. In a future paper we intend to explore qualitative components of the MHC (client relationships and interagency collaboration). As in previous research (6), clinical characteristics did not play a role in increasing rearrest for new criminal charges.

In another study that examined recidivism among persons with mental illness, Solomon and colleagues (7) found that increased incarceration rates were associated with increased intensive case management. They argued that increased monitoring of behavior associated with intensive case management resulted in mental health care providers' contacting probation and parole officers about noncompliance that may in fact have initiated incarceration. However, in the study by Solomon and colleagues, there was not an MHC in operation with the explicit goal of working together to keep mentally ill offenders out of jail.

Another limitation is that it is unclear what aspect of graduation status led to reduced rearrest. It is likely that clients who opted in to the MHC and stayed for the 12 to 14 months required to graduate were more motivated to make life changes and were thus more open to high levels of supervision and intensity of services provided than those who refused participation, did not comply with MHC requirements, or opted out. Motivation to change as well as other explanatory variables that remained uncontrolled in our analysis may account for some of the association between rearrest and graduation status.

To determine whether graduation status was simply a proxy measure for time in the MHC, a separate model (not presented here) was run, in which number of days in the MHC was substituted for the two MHC status variables (graduated and still in the MHC at 365 days compared with terminated clients). However, number of days in the MHC was not found to be a significant predictor of rearrest.

We chose to include the index arrest (the conviction that brought offenders before the MHC) in the total number of arrests during the 12-month preenrollment period. We believed that, given the history of involvement with the criminal justice system in this sample, it would be arbitrary to exclude the index arrest. The average number of lifetime arrests for this sample was six (as recorded in the Clark County Department of Corrections MIS database), the number of arrests 12 months before the MHC was 1.99, and the number 24 months before the MHC was 2.4, including the index arrest. However, it could be argued that including the index arrest created an artificially inflated pre-mean in that the prearrest number must be at least one to be eligible for the MHC. A more conservative estimate would result by excluding the index arrest, which would result in a pre-mean of .99, which, compared with the post-mean of .48, still demonstrates a significant reduction in arrests (paired t=5.9, df=367, p<.001).

The past two years has seen a great deal of debate among Clark County MHC stakeholders about whether to expand the MHC to include persons with felony charges. Although the index offense for this population of 368 mentally ill offenders had to be a misdemeanor for the person to qualify for the MHC, 34 percent had prior felony charges on their records. Those with prior felony arrests were not more likely to reoffend than misdemeanants, indicating that the MHC may have a positive impact on recidivism rates if it is expanded to include those with felony offenses.

More outcome studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of MHCs. To truly assess the effectiveness of MHCs, randomized trials comparing clients served by an MHC with a control group are needed. Future research could also examine the relative effectiveness of the features of existing MHCs, such as the degree of interaction and service coordination between mental health services and the court processes, pre-plea versus post-plea enrollment criteria, felony versus misdemeanor courts, use of sanctions and threat of sanctions on client outcomes, and the role and relationship between the judge and clients.

Steadman and colleagues (8) have stated that, in addition to future outcomes research, there is a need for a common structured model or set of operational criteria for defining an MHC. Two presiding judges of MHCs, Judge Ginger Lerner-Wren of Broward County and Judge Fritzler of Clark County, are working on documenting the key components and innovative features of MHCs (9).

Conclusions

The Clark County Mental Health Court program served mentally ill offenders, many of whom not only were repeat offenders but also consumed the time and resources of the criminal justice system by not following through with court processes, repeatedly violating probation and community supervision, and failing to appear in court. The MHC program was successful in reducing both the number of individuals who committed crimes and the total number of crimes committed by MHC clients. The criminal justice system benefited from working closely with the mental health system to provide comprehensive services for mentally ill offenders.

Ms. Herinckx, Ms. Swart, and Mr. Ama are affiliated with the Regional Research Institute for Human Services at Portland State University, P.O. Box 751, Portland, Oregon 97207 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Dolezal and Mr. King are with the Clark County Department of Community Services and Corrections in Vancouver, Washington.

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of 368 participants in a mental health court (MHC) program

|

Table 2. Mental health service use and arrests before and after enrollment in a mental health court (MHC) program in a sample of 320 clients

|

Table 3. Results of a logistic regression analysis of rearrest in a sample of 368 clients of a mental health court (MHC) program

1. Goldkamp JS, Irons-Guynn C: Emerging judicial strategies for the mentally ill in the criminal caseload: mental health courts in Fort Lauderdale, Seattle, San Bernardino and Anchorage. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2000Google Scholar

2. McGaha A, Boothroyd RA, Poythress NG, et al: Lessons from the Broward County mental health court evaluation. Program Planning and Evaluation 25:125–135,2002Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Boothroyd RA, Poythress NG, McGaha A, et al: The Broward mental health court: process, outcomes, and services utilization. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 26:55–71,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Trupin E, Richards H: Seattle's mental health courts: early indicators of effectiveness. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 26:33–53,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Fritzler RB: How one misdemeanor mental health court incorporates therapeutic jurisprudence, preventive law, restorative justice, in Management and Administration of Correctional Health Care. Edited by Moore JM. Kingston, NJ, Civic Research Institute, 2003Google Scholar

6. Feder L: A profile of mentally ill offenders and their adjustment in the community. Journal of Psychiatry and the Law 19:79–98,1991Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Solomon P, Draine J, Marcus C: Predicting incarceration of clients of a psychiatric probation and parole service. Psychiatric Services 53:50–56,2002Link, Google Scholar

8. Steadman HJ, Davidson S, Brown C: Mental health courts: their promise and unanswered questions. Psychiatric Services 52:457–458,2001Link, Google Scholar

9. Lerner-Wren G: Broward County mental health court: an innovative approach to the mentally disabled in the criminal justice system. Presented at the Symposium on Mental Health, New Jersey's Institute of Law and Mental Health, Seton Hall Law School, Newark, New Jersey, 2003Google Scholar