One-Year Housing Arrangements Among Homeless Adults With Serious Mental Illness in the ACCESS Program

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the various living arrangements among formerly homeless adults with mental illness 12 months after they entered case management. METHODS: The study surveyed 5,325 clients who received intensive case management services in the Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program. Living arrangements 12 months after program entry were classified into six types on the basis of residential setting, the presence of others in the home, and stability (living in the same place for 60 days). Differences in perceived housing quality, unmet housing needs, and overall satisfaction were compared across living arrangements by using analysis of covariance. RESULTS: One year after entering case management, 37 percent of clients had been independently housed during the previous 60 days (29 percent lived alone in their own place and 8 percent lived with others in their own place), 52 percent had been dependently housed during the previous 60 days (11 percent lived in someone else's place, 10 percent lived in an institution, and 31 percent lived in multiple places), and 11 percent had literally been homeless during the previous 60 days. Clients with less severe mental health and addiction problems at baseline and those in communities that had higher social capital and more affordable housing were more likely to become independently housed, to show greater clinical improvement, and to have greater access to housing services. After the analysis adjusted for potentially confounding factors, independently housed clients were more satisfied with life overall. However, no significant association was found between specific living arrangements and either perceived housing quality or perceived unmet needs for housing. CONCLUSIONS: Living independently was positively associated with satisfaction of life overall, but it was not associated with the perception that the quality of housing was better or that there was less of a need for permanent housing.

A major goal of services for homeless persons with mental illness is to provide an exit from homelessness. Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of a variety of interventions in facilitating an exit from homelessness, including community outreach (1,2,3,4,5,6), assertive community treatment (7,8,9,10,11), and various types of supported housing or residential treatment (12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23).

However, there has been relatively little study of the various types and characteristics of living arrangements that result from these services. Several questions have yet to be addressed: What types of housing arrangements do clients obtain on exiting homelessness? With whom do they live? Which client and community characteristics are associated with which kind of residence? What percentage are independently housed? Is independent housing associated with greater life satisfaction?

The concept of independent housing, although highly valued, has not been well defined in view of the wide variety of living arrangements obtained by formerly homeless individuals. Apart from the most widely used definition of living in one's own apartment, room, or house, few systems for classifying living arrangements have been presented in the published literature. Two exceptions are the detailed typology of nine longitudinal housing patterns that was developed by Hough and colleagues (14) and the more recent conceptual framework that was developed by Rog and Randolph (24), which identifies key dimensions of supported housing for persons with serious mental illness. Unfortunately, such detailed descriptive data on living arrangements are unavailable from most studies.

Our study characterized living arrangements during a 60-day period more simply as living alone in one's own apartment, room, or house; living in one's own place with others; living in someone else's place; living in an institution (health care or penal); living in multiple settings; and being homeless.

In a recent review of studies of housing among seriously mentally ill persons, Newman (20) identified three ways in which researchers have treated various housing attributes: housing as an input (an independent variable predicting outcomes), housing as an output (a dependent variable predicted by patient and community characteristics), and housing as both an input and an output (sociodemographic and client characteristics treated as independent variables, with housing quality and satisfaction treated as dependent variables). In this study we used the third approach, first examining the attributes of the client's living arrangement at the 12-month follow-up as an output or outcome of client and community characteristics and service use and then examining living arrangement as an input or predictor of measures of housing quality, perceived unmet needs for housing, and perceived overall quality of life at the 12-month follow-up.

We hypothesized that clients who were living independently at the 12-month follow-up would show more favorable housing outcomes than those in other housing categories and those who were homeless. More specifically, we expected that independently housed clients would be less likely to perceive a need for permanent housing, would be more likely to report that their housing was of higher quality, and would be more likely to report higher overall satisfaction than other clients.

Methods

Overview of the ACCESS program

The Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program provided funding and technical support from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to 18 programs in 15 cities to promote systems integration and provide intensive case management to 100 clients per site per year (25). Entry criteria for the ACCESS program included being homeless (that is, living in an emergency shelter, outdoors, or in a public or abandoned building for seven of the previous 14 days), having severe mental illness, and having limited involvement in ongoing community treatment (26). Eligible participants who provided written informed consent were recruited from 1994 to 1998. Data were obtained at program entry, three months later, and 12 months later.

Sample

Our study examined the living arrangements of ACCESS clients who were interviewed 12 months after entering the program and for whom living arrangement data were available (N=5,325, or 74 percent of the total number of participants in the ACCESS program).

Measures

Living arrangements. Clients' living arrangements were classified into six categories on the basis of clients' responses to two questions. The first question documented the number of nights spent in 12 different residential settings during the past 60 days, including living in one's "own apartment, room, or house." The second question, which asked how often clients saw persons whom they felt close to during the past 60 days, included a response option "live with the person," indicating the presence of others in the home or residence.

From these data we created six mutually exclusive living arrangement categories, including two independently housed categories (living in one's own place alone or in one's own place with others), three dependently housed categories (living in someone else's place, in an institution, or in multiple places), and a literally homeless category (living in shelters, outdoors, in abandoned buildings, and so forth).

We classified living in someone else's place as dependently housed because of the subordinate position of an adult living in someone else's house. Clients who were married, cohabitating, or sharing rent on an equal basis with others in the home were presumed to live in their own homes with others and were considered to be independently housed.

Individual characteristics. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics included age, gender, race and ethnicity, years of education, and monthly income. Psychiatric problems, alcohol use, and drug use were assessed with the composite problem scores from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (27). Diagnoses were based on the working clinical diagnoses of the admitting clinicians.

A mental health problems index was created by averaging standardized z scores on three mental health outcome measures (Cronbach's alpha=.75): the ASI psychiatric composite problem index, a depression scale derived from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (28), and the psychotic symptom scale derived from the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview (PERI) (29). Higher scores represented more severe psychiatric symptoms.

Interviewers also rated manifest psychotic behavior by using a 13-item measure that was developed from the PERI. This measure documented unusual speech, affect, agitation, responses to internal stimuli, and delusions (Cronbach's alpha=.76).

Community adjustment was assessed with measures of involvement with the criminal justice system, family instability, and social support. Family instability was assessed as the sum of a 12-item scale that addressed experiences before the age of 18, such as parental separation, divorce, death and poverty; Cronbach's alpha=.69 (30). Social support was assessed as the average number of persons who would help the client with a loan or transport or in an emotional crisis; Cronbach's alpha=.74 (31).

Clinical change. Three clinical change measures were calculated by subtracting baseline values from follow-up values of the ASI alcohol and drug use subscales and of the mental health composite index. Clinical improvement was denoted by declining or negative scores over time.

Change in supportive services. Use of outpatient psychiatric services was measured dichotomously as the proportion of clients who received any outpatient psychiatric or substance abuse treatment services during the past 60 days. Four dichotomous housing-related service variables measured the percentage of clients who received Section 8 vouchers, public housing, housing case management, and any services from a public housing authority.

Measures of change in the availability of supportive services—related to both psychiatric and housing services—were calculated by subtracting baseline values from follow-up values—the same method that was used in computing clinical change. Here, unlike the clinical change measure, a positive change in the score was desirable and reflected an increase in the use of services.

Housing outcomes. Housing quality was assessed by using a housing problem checklist (32). Clients who were housed were asked to what extent they experienced problems (from 0, no problem, to 2, big problem) on 12 items, for example, the amount of space or privacy or the proper functioning of plumbing. A housing problem index score was then created by using the mean problem response across the 12 items (Cronbach's alpha=.81). The housing problem index score was then subtracted from 2 (the maximum problem value) to compute a positive housing quality score.

Perceived housing needs were documented with respect to three types of housing: immediate shelter, transitional housing, and permanent housing. These needs were assessed through questions that asked whether or not clients needed each of 19 types of services, the three most important of these services, and the extent to which they were receiving each of these three services. Housing needs were considered unmet if they were among clients' top three needs and if they were either not met at all or were only partially met.

Quality of life. Quality of life was assessed by using four subscales from the Lehman Quality of Life Interview (33), which were composed of items that were assessed on a 7-point scale of delighted to terrible. The four subscales included satisfaction with safety in the neighborhood (five items, Cronbach's alpha=.82), satisfaction with clients' relationship with family (three items, Cronbach's alpha=.83), satisfaction with the amount of friendship that they had (six items, Cronbach's alpha=.87), and satisfaction with life in general (one item).

Environmental characteristics. Measures were also available for the community's housing affordability, service systems integration, and social capital. Housing affordability data were obtained from the 1990 census and were defined as the proportion of households that paid less than 30 percent of their income for housing.

Service systems integration was assessed in each city by using in-person surveys that were developed to measure the number and strength of interorganizational ties between agencies that provide services to homeless persons with mental illness. The methods that were used to assess service systems integration are described in detail elsewhere (34).

Social capital—or level of civic involvement or social trust—was measured at the county level by following the concepts and methods developed by Putnam (35,36). Higher social capital scores indicated greater participation among residents of a given community in various civic activities, including attending club meetings, working on community projects, volunteering, and voting. A previous analysis of data from the ACCESS program defined these measures in greater detail and showed that social capital was associated with a greater likelihood that clients would exit homelessness (37).

Analyses

First, client and community characteristics were compared at baseline across the six types of living arrangements by using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was then used to compare 12-month changes in clinical status and use of supportive services across living arrangements while adjusting for baseline characteristics. A final set of ANCOVAs were used to compare the housing experience across living arrangement categories while adjusting for potentially confounding factors.

ANCOVAs were conducted by using SPSS 10.0 statistical analysis software (38). The six-level living situation variable was included as the independent class variable of principal interest in all models, with significant baseline and change variables included as covariates in respective models. The mean values reported in Tables 3 and 4 are ordinary least-squares means that adjusted for significant baseline and change covariates, respectively. Linearly independent pairwise comparisons were also evaluated.

Results

Living arrangements

One year after entering case management, 37 percent of clients had been independently housed during the past 60 days; 29 percent had been living in their own place alone, and 8 percent had been living in their own place with others (Tables 1 and 2). Nearly all of those living in their own place with others lived with a family member, either a spouse or a child. More than half of the clients (52 percent) had been dependently housed during the past 60 days; 11 percent lived in someone else's place, 10 percent lived in an institution, and nearly one-third (31 percent) had lived in multiple places during the past 60 days. The remaining 11 percent of clients reported being literally homeless throughout the past 60 days.

Among the 26 percent of all the ACCESS clients for whom housing outcome data were not available—that is, those who were unable to be located and interviewed at the 12-month follow-up—and were excluded from this study, it is likely that most were either dependently housed or literally homeless.

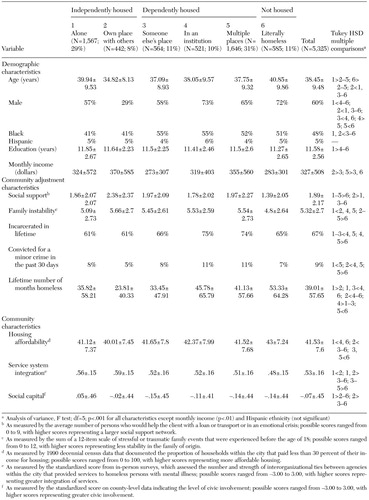

Baseline characteristics

Clients who lived alone tended to be older, to be more educated, to have fewer psychiatric and substance use problems at baseline, and to live in communities with higher social capital and more affordable housing (Tables 1 and 2).

Clients who lived in their own place with others were more likely to be younger, to be female, to have higher incomes and more extensive social support networks, and to have spent less time homeless during their lifetimes than other clients. They were the most likely to have a diagnosis of major depression, were the least likely to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and had the fewest psychiatric problems overall.

Clients who lived independently in their own place—either alone or with others—were less likely to be black, had fewer problems with drugs and alcohol, had spent less time homeless during their lifetimes, and lived in communities with more integrated service systems than other clients.

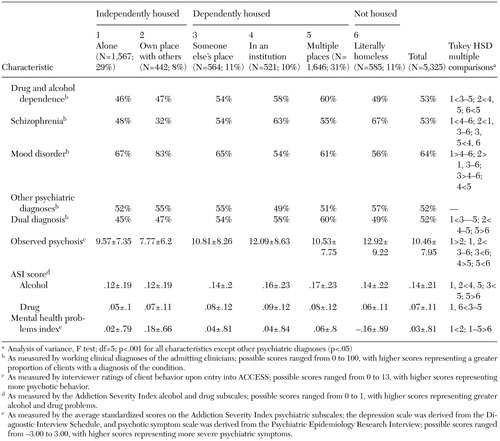

Few differences were found between clients who lived in a dependent housing situation—those who lived in someone else's place, an institution, and in multiple places. Compared with independently housed clients, dependently housed clients were more likely to be black, to have less education, to have more problems with drugs and alcohol, to have more extensive criminal histories, to have been homeless longer, and to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

Clients who were homeless at the 12-month follow-up had the lowest incomes at baseline, had the most psychiatric problems, had the smallest social support networks, had been homeless longer during their lifetimes, and had lived in communities with the least affordable housing and the least integrated service systems.

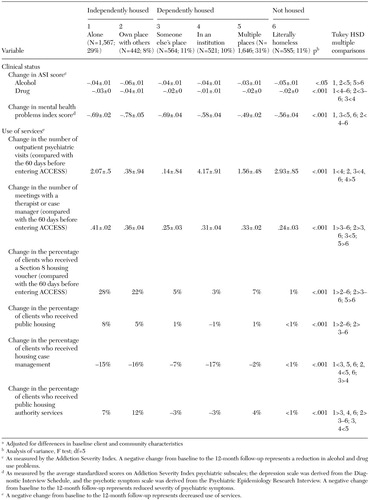

Changes in clinical status and use of services

Each of the groups showed clinical improvement in clinical status, use of psychiatric services, and use of housing services 12 months after entering case management (Table 3). Independently housed clients showed greater decreases in alcohol use compared with clients who were unstably housed and greater decreases in drug use compared with clients in all other living arrangement categories. Independently housed clients and those living in someone else's place showed greater improvement in mental health problems than clients in other groups.

The overall increase in use of total outpatient psychiatric services during the past two months was greatest among institutionalized clients and homeless clients. This increase may be due to the provision of day treatment, case management, and other mental health services by shelters and drop-in centers. Independently housed clients were more likely to report having a primary case manager.

Independently housed clients were also more likely to receive Section 8 housing vouchers, public housing, and public housing authority services, but they reported the greatest decline in use of housing case management services. These clients possibly received more housing case management services initially, but their use of housing case management declined after they were housed.

Housing outcomes

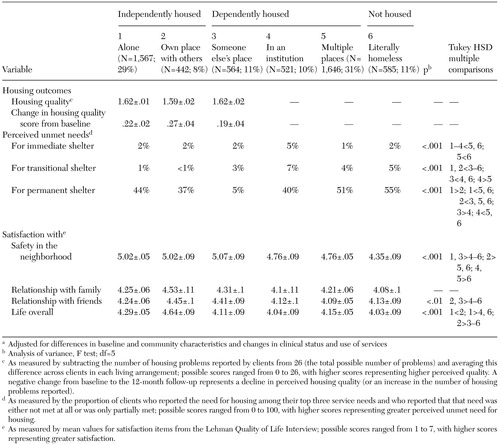

Perceived housing quality. No significant differences in perceived housing quality were found between clients who lived independently and those who lived in someone else's place (Table 4). The change in housing quality (follow-up minus baseline) did not differ across groups.

Unmet housing needs. As expected, clients who were independently housed in the community reported fewer unmet needs for immediate shelter (40 clients, or 2 percent) than clients who were institutionalized (26 clients, or 5 percent), clients who lived in multiple places (165 clients, or 10 percent), or clients who were homeless (117 clients, or 20 percent). The relatively small proportion of homeless clients who reported a need for immediate shelter is surprising, but it may reflect a sufficient number of available shelter beds, the presence of more pressing needs and concerns, or a preference for more permanent housing.

Perceived need for transitional housing was small among all groups, ranging from less than 1 percent (two clients) among those living in someone else's place to 7 percent (36 clients) among those living in institutional settings.

Perceived need for permanent housing was relatively high, even among clients who were living alone—the group of clients that was seen as the most independent. The proportion of clients who reported having unmet needs for permanent housing ranged from 37 percent (164 clients) among those who lived independently with others to 55 percent (322 clients) among those who were homeless.

Quality of life. Independently housed clients and those living in someone else's place were more satisfied with the safety in their neighborhoods than other clients. Not surprisingly, clients who were homeless felt the least safe.

Surprisingly, no significant differences were found across living arrangements in satisfaction with family relationships, even though most clients who lived in their own place with others lived with members of their family.

Clients who lived with others, either in their own place or in someone else's place, were more satisfied both with the amount of friendship in their lives and with their lives in general than clients who lived alone, who were institutionalized, who were unstably housed, or who were homeless.

Clients who were independently housed were more satisfied with their lives overall than homeless clients, who reported the lowest satisfaction with their quality of life.

Discussion and conclusions

One year after entering intensive case management, 37 percent of formerly homeless persons with serious mental illness were stably and independently housed. Clients who had less severe mental health and addiction problems when they entered the ACCESS program were the most likely to become independently housed, showed the greatest clinical improvement, and had more access to housing services. Those living in communities with higher social capital and lower housing costs were also more likely to become independently housed.

After the analysis adjusted for potentially confounding sociodemographic and clinical factors, independently housed clients were found to be more satisfied with their life overall. However, clients who lived independently did not report greater perceived housing quality or fewer unmet housing needs than others, as hypothesized.

One possible explanation for the lack of significant differences in the area of housing quality is that the global housing quality measure included items that gauged both the housing unit and the neighborhood and that addressed several dimensions, which may vary independently across living situations. For example, persons living on their own may like the amount of privacy they have, but they may dislike the physical conditions of the subsidized buildings in which they live.

Consistently high rates of perceived unmet needs for permanent housing across living arrangements, even among clients who were independently housed, suggests that permanent housing remains among the top three concerns of formerly homeless persons with serious mental illness. Persons who are independently housed may be concerned about being able to keep their current housing or their Section 8 rental subsidies, which make their rents relatively affordable. Those who live in institutions or other settings may not be able to afford permanent housing because of a lack of income or limited availability of long-term rental subsidies.

Our findings should be considered in light of several methodologic limitations: the measurement of housing outcomes was based on client reports, not objective measures of housing quality; detailed data on housing stability—that is, the total number of moves during the first ten months in case management—were not available; and unmeasured differences in client characteristics may have confounded our analyses.

Limitations notwithstanding, the data reported here may be useful to policy makers, program administrators, and program evaluators as benchmarks, or comparisons, of housing outcomes for intensive case management programs that serve homeless individuals who are seriously mentally ill.

The authors are affiliated with the VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 950 Cambell Avenue, West Haven, Connecticut 06516 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Mares is also with the department of psychiatry at the School of Medicine at Yale University. Dr. Rosenheck is also with the department of psychiatry at the School of Medicine and the School of Epidemiology and Public Health at Yale University.

|

Table 1. Baseline demographic and community characteristics (mean±SD) of clients in the Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program, by living arrangement for the past 60 days at 12-month follow-up

|

Table 2. Baseline clinical characteristics (mean±SD) of clients in the Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program, by living arrangement for the past 60 days at 12-month follow-up

|

Table 3. Changes in clinical status and use of services from baseline to 12-month follow-up for clients in the Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program, by living arrangement for the past 60 daysa

a Adjusted for differences in baseline client and community characteristics

|

Table 4. Scores on housing and satisfaction outcome measures among clients in the Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program, by living arrangement for the past 60 days at 12-month follow-upa

a Adjusted for differences in baseline and community characteristics and changes in clinical status and use of services

1. Rosenheck RA, Gallup PA, Frisman LK: Health care utilization and costs after entry into an outreach program for homeless mentally ill veterans. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:1166–1171, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Bybee D, Mowbray CT, Cohen E: Short versus longer term effectiveness of an outreach program for the homeless mentally ill. American Journal of Community Psychology 22:181–209, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Shern DL, Felton CJ, Hough RL, et al: Housing outcomes for homeless adults with mental illness: results from the second-round McKinney program. Psychiatric Services 48:239–241, 1997Link, Google Scholar

4. Lam JA, Rosenheck RA: Street outreach for homeless persons with serious mental illness: is it effective? Medical Care 37:894–907, 1999Google Scholar

5. Rosenheck RA: Cost-effectiveness of services for mentally ill homeless people: the application of research to policy and practice. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1563–1570, 2000Link, Google Scholar

6. Shern D, Tsemberis S, Anthony W, et al: Serving street-dwelling individuals with psychiatric disabilities: outcomes of a psychiatric rehabilitation clinical trial. American Journal of Public Health 90:1873–1878, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S, et al: Preventing recurrent homelessness among mentally ill men: a "critical time" intervention after discharge from a shelter. American Journal of Public Health 87:256–262, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wolfe N, Helminiak TW, Morse GA, et al: Cost-effectiveness evaluation of three approaches to case management for homeless mentally ill clients. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:341–348, 1997Link, Google Scholar

9. Morse G: A review of case management for people who are homeless: implications for practice, policy, and research, in Practical Lessons: The 1998 National Symposium on Homelessness Research. Washington, DC, US Department of Housing and Urban Development, 1999Google Scholar

10. Lehman AF, Dixon LB, Kernan E, et al: A randomized trial of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 174:346–352, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Rosenheck RA, Frisman LK, Kasprow W: Improving access to disability benefits among homeless persons with mental illness: an agency-specific approach to services integration. American Journal of Public Health 89:524–528, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Barrow SM, Hellman F, Lovell AM, et al: Effectiveness of Programs for the Mentally Ill Homeless: Final report. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1989Google Scholar

13. Hurlburt MS, Wood PA, Hough RL: Providing independent housing for the homeless mentally ill: a novel approach to evaluating long-term longitudinal housing patters. Journal of Community Psychology 24:291–310, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Hough RL, Harmon S, Tarke H, et al: Supported independent housing: implementation issues and solutions in the San Diego Project, in Mentally Ill and Homeless: Special Programs for Special Needs. Edited by Breakey WR, Thompson JW. Reading, United Kingdom, Harwood Academic Publishers, 1997Google Scholar

15. Ogilvie RJ: The state of supported housing for mental health consumers: a literature review. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 21:122–131, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Ridgway P, Rapp CA: The Active Ingredients of Effective Supported Housing: A Research Synthesis. Lawrence, Kans, University of Kansas, 1997Google Scholar

17. Schutt RK, Goldfinger SM, Penk WE: Satisfaction with residence and with life: when homeless mentally ill persons are housed. Evaluation and Program Planning 20:185–194, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Shern DL, Felton CJ, Hough RL, et al: Housing outcomes for homeless adults with mental illness: results from the second-round McKinney program. Psychiatric Services 48:239–241, 1997Link, Google Scholar

19. Tsemberis S, Eisenberg RF: Pathways to housing: supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 51:487–493, 2000Link, Google Scholar

20. Newman SJ: Housing attributes and serious mental illness: implications for research and practice. Psychiatric Services 52:1309–1317, 2001Link, Google Scholar

21. Wolf J, Burnam A, Koegel P, et al: Changes in subjective quality of life among homeless adults who obtain housing: a prospective examination. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 36:391–398, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Fakhoury W, Murray A, Shepherd G, et al: Research in supported housing. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 37:301–315, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Rosenheck RA, Kasprow W, Frisman, et al: Cost-effectiveness of supported housing for homeless persons with mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:940–951, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Rog DJ, Randolph FL: A multisite evaluation of supported housing: lessons learned from cross-site collaboration. New Directions for Evaluation 94:61–72, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

25. Randolph F, Blasinsky M, Morrissey JP, et al: Overview of the ACCESS program. Psychiatric Services 53:945–948, 2002Link, Google Scholar

26. Rosenheck Robert, Lam JA: Homeless mentally ill clients' and providers' perceptions of service needs and clients' use of services. Psychiatric Services 48:381–386, 1997Link, Google Scholar

27. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26–33, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan TR: The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Archives of General Psychiatry 38:381–389, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Dohrenwend BP: Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview (PERI). New York, Columbia University, Social Psychiatry Research Unit, 1982Google Scholar

30. Kadushin C, Boulanger G, Martin I: Long term reactions: some causes, consequences, and naturally occurring social support systems, in Legacies of Vietnam IV. House Committee, print no 14, 1981Google Scholar

31. Vaux A, Athanassopulou M: Social support appraisals and network resources. Journal of Community Psychology 15:537–556, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Newman SJ, Reschovsky JD, Kaneda K, et al: The effects of independent living on persons with chronic mental illness: an assessment of the Section 8 Certificate program. Milbank Quarterly 72:171–198, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51–52, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Morrisey J, Calloway M, Johnsen M, et al: Service system performance and integration: a baseline profile of the ACCESS demonstration sites. Psychiatric Services 48:374–380, 1997Link, Google Scholar

35. Putnam RD: Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1993Google Scholar

36. Putnam R: Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York, Simon and Schuster, 2000Google Scholar

37. Rosenheck RA, Morrissey J, Lam J, et al: Service delivery and community: social capital, service systems integration, and outcomes among homeless persons with severe mental illness. Health Services Research 36:691–710, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

38. SPSS Incorporated. SPSS 10.0 for Windows. Chicago, 1999Google Scholar