Use of Claims Data to Examine the Impact of Length of Inpatient Psychiatric Stay on Readmission Rate

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study analyzed the impact of length of stay for inpatient treatment of psychiatric disorders on readmission rates. METHODS: Hospitalization data were obtained from the MarketScan data set collected by Medstat. The instrumental variable method, an econometric technique, was used to estimate the impact of length of stay on the rate of readmission for 5,735 persons who had at least one discharge with a primary diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder during 1997 and 1998. RESULTS: Decreasing length of stay below ten days led to an increase in the readmission rate during the 30 days after discharge. Decreasing the length of stay from seven to six days increased the expected readmission rate from .04 to .047 (17.5 percent), whereas decreasing length of stay from four to three days increased the readmission rate from .09 to .136 (51.1 percent). CONCLUSION: Decreasing length of stay for inpatient psychiatric treatment increased the readmission rate. The use of instrumental variables could help better estimate the value of mental health services when using observational data.

Managed care has reduced the mean length of stay for psychiatric hospitalizations (1,2), which has resulted in decreased costs and has raised concerns about the quality of care (3,4,5,6,7,8). There are no commonly accepted length-of-stay guidelines for inpatient care of psychiatric conditions, as there are for some medical conditions, and the length of inpatient psychiatric treatment could be subject to substantial variation (9).

Psychiatric readmissions are frequently used as a measure of an adverse outcome (4,10). A psychiatric readmission is argued to be an adverse outcome because it is costly and occurs when the relapse to the illness is so severe that less restrictive treatments are insufficient (11,12). We theorized that inpatient psychiatric treatment would be beneficial for psychiatric disorders and that patients whose length of stay is shortened would have worse outcomes, which would be measured by a higher readmission rate.

Studies that have evaluated the relationship between length of stay and rate of readmission have reported contradictory results. Wickizer and colleagues (7) reported that children and adolescents whose length of stay was restricted by utilization management were more likely to be readmitted. More recently Heeren and colleagues (6) observed that in a psychogeriatric unit, when length of stay decreased the readmission rate increased. Another study found that patients with schizophrenia who were discharged before 30 days of admission had higher recidivism rates (13). On the other hand, some studies did not find a negative correlation between length of stay and readmissions (14,15)—that is, a shorter stay with a higher readmission rate—and some studies even found a positive correlation between length of stay and readmissions (16,17,18)—that is, a shorter stay with a lower readmission rate.

Because patients are not randomly assigned to groups with shorter or longer hospital stays, it is difficult to make causal inferences about length of stay and readmission rate. A potential selection bias exists, because patients who stay longer in the hospital are more likely to be sicker or homeless or to lack social supports. Patients who are hospitalized longer could also be more likely to be readmitted, not because of the longer length of stay but because of these other factors that are positively correlated with longer stays and higher rates of readmission. Because of this positive bias, the negative effect of length of stay on readmission rate could be underestimated, or if the positive bias is larger than the therapeutic impact of length of stay on readmission rate, the effect could be inverted and a positive effect of length of stay on readmission rate could be found.

In our study, we used administrative data on hospital discharges in the United States during 1997 and 1998 to characterize the impact of length of stay on the rate of readmission for inpatient treatment of psychiatric disorders. To address the problem of self-selection we used instrumental variables estimation, which permits causal inferences with observational data (19,20).

Methods

Data

We used the MarketScan data set collected by Medstat. Medstat is a health care information company that provides market intelligence and benchmark databases for managing the cost and quality of health care. The MarketScan data set included claims data on hospitalizations from 5,735 persons across the United States who had one or more discharges with a primary psychiatric diagnosis during 1997 and 1998. These data were not intended to be nationally representative. The data set included only information from employer-based private health insurance companies that share their data with Medstat. A disproportionately high percentage of the discharges analyzed occurred in Michigan (24 percent), Massachusetts (11 percent), Georgia (9 percent), and Florida (8 percent).

Inpatient hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder were identified by using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision clinical modification codes.

We created dummy variables for patient demographic characteristics; diagnostic categories, for example, psychotic disorders, adjustment disorders, major depression, and bipolar disorder; and the type of primary payer, that is, whether patients used a fee-for-service plan or a managed care plan. For patients who had more than one admission for a psychiatric disorder during this two-year period, we used information on these characteristics from the first admission. Also, for patients with multiple admissions, we calculated length of stay only for the first admission. We counted the subsequent number of readmissions that each patient had during the 30 days that followed the index hospitalization. Hospitalizations that ended during December 1998 were used to identify readmissions but were otherwise excluded from the analyses.

Patient characteristics

Patients were classified as living in an urban or a rural metropolitan statistical area, as defined by the Bureau of the Census and the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, and by the type of primary payer. Gender and age were also included as variables in the analyses.

Statistical analyses

Because ordinary least-squares analyses would give a biased estimate of the impact of length of stay on readmission rate, a two-stage regression that used instrumental variables was necessary. If length of stay was correlated with unobserved severity of the illness (that is, a higher suicide risk or poorer social supports, which are not accounted for in the diagnostic information available in administrative data and would influence the readmission rate), any estimated impact of length of stay on readmission could actually result from severity of illness, as opposed to length of stay. A standard method for correcting this problem is the instrumental variable method (20). With this method, instead of using length of stay as an explanatory variable in the regression, we used the predicted value of length of stay. In order to have a useful value of the predicted length of stay, it was necessary to use a variable that strongly predicted length of stay—that is, a variable that worked as a proxy for length of stay—but that did not have a direct impact on the readmission rate. This variable is called the instrumental variable. The two stages of the technique are two regressions. In the first one, the instrumental variable was used to predict length of stay. In the second regression, the predicted value of length of stay—from the first regression—was used as an explanatory variable for readmission rate. In both regressions, we also controlled for demographic characteristics and diagnostic information.

We used as the instrumental variable the mean length of stay for all psychiatric admissions in the zip code of the hospital where the hospitalization occurred. This mean length of stay is a good instrumental variable because the mean length of stay at the regional level has a direct and strong impact on the length of stay for a particular patient, and it does not directly affect the readmission rate.

Because admissions in the same region are not completely independent events, we corrected the standard errors for clustering by hospital zip code. Alternatively, we also ran an ordinary least-squares regression analysis, controlling for demographic characteristics and diagnostic information, to compare this estimation with the instrumental variable method model.

Because both length of stay and readmission rate had very skewed distributions, before running the ordinary least-squares regression or the two-stage instrumental variable method model, we transformed length of stay to its logarithm and transformed readmission rate by adding 1 and then taking its logarithm. Because of these logarithmic transformations, when we obtained the predicted values of readmission rate for each value of length of stay, we adjusted the estimations by multiplying by a smearing factor (21). Because we found heteroscedasticity of the residuals in the regression of readmission rate on length of stay, we obtained a different smearing estimate for each possible length of stay (22).

Results

Descriptive statistics

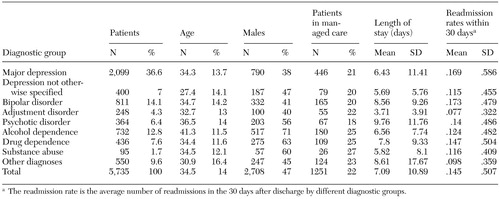

The main characteristics of psychiatric hospitalizations by diagnostic group for persons who had one or more discharges with a primary psychiatric diagnosis in 1997 and 1998 are shown in Table 1. Of the 5,735 patients who had at least one psychiatric hospitalization during the observation period, 5,123 (89.3 percent) were not readmitted during the 30 days of observation after discharge, 485 (8.5 percent) had one readmission, and 127 (2.2 percent) had two or more readmissions. The overall mean readmission rate was .145 and the mean length of stay for the first psychiatric hospitalization was 7.09 days. The diagnostic groups that were likely to include more severely ill patients had the highest mean length of stay and a relatively high readmission rate. Patients with a diagnosis of psychotic disorder or bipolar disorder had the two longest mean lengths of stay (9.76 and 8.56, respectively) and a relatively high readmission rate (.140 and .173, respectively). The group of patients with adjustment disorder had the lowest mean length of stay and the lowest mean readmission rate (3.71 and .077, respectively).

Predicting length of stay with first-stage regression

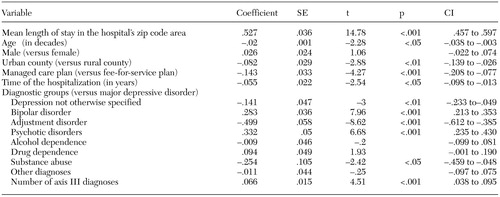

To conduct the two-stage regression for the instrumental variable method, we first ran a regression to obtain the predicted value of length of stay. The effects of the different explanatory variables on length of stay are shown in Table 2. Our instrumental variable—the mean length of stay for all psychiatric admissions in the zip code of the hospital where the hospitalization occurred—was a powerful predictor of length of stay (t=14.78, p<.001). The finding that local mean length of stay is a strong predictor of each individual's length of stay is consistent with our hypothesis and it is also necessary for the instrumental variable method to give consistent estimates, which are unbiased when the sample is large enough. Significant predictors of a shorter stay were age, living in an urban metropolitan statistical area, and having a managed care payer. Patients with indicators of higher severity of illness, such as psychotic disorders or major mood disorders, had longer stays. The timing of the hospitalization was significantly and negatively correlated with length of stay. That is, the later it was during the period of observation (closer to late 1998), the shorter the hospitalization.

Ordinary least-squares regression analyses

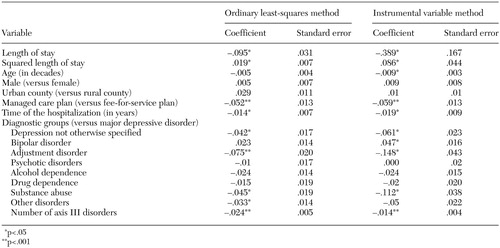

According to our working hypothesis and the descriptive data, using ordinary least-squares analyses would give a biased estimate of the impact of length of stay on readmission rate. When we obtained such an estimate, we found that length of stay had a small, but significantly negative, impact on readmission rate, and the effect was not linear—that is, the negative impact on readmission rate was of a higher magnitude when length of stay was shorter. The results of the ordinary least-squares analyses are shown in Table 3. Because of the logarithmic transformations of length of stay and readmission rate and because of the presence of both length of stay and the squared length of stay as explanatory variables, the coefficients of -.095 and .019 found for length of stay and the squared length of stay, respectively, indicate that a decrease in length of stay from seven to six days would increase the readmission rate from .118 to .121 (2.5 percent) and a decrease in length of stay from four to three days would increase the readmission rate from .135 to .144 (6.7 percent)

Impact of length of stay on readmission rate

When we used the instrumental variable method, we found that length of stay had a greater and significantly negative impact on readmission rate than when we used the ordinary least-squares method. We found a significantly negative impact—decreasing the stay in the hospital increased the readmission rate. The effect was not linear—that is, the negative impact on readmission rate was of a higher magnitude when length of stay was shorter. Results of the instrumental variable method are shown in Table 3. Because of the logarithmic transformations of length of stay and readmission rate and because of the presence of both length of stay and squared length of stay as explanatory variables, the coefficients of -.389 and .086 that were found for length of stay and squared length of stay, respectively, indicate that decreasing the length of stay from seven to six days increased the expected readmission rate from .040 to .047 (17.5 percent), whereas decreasing the length of stay from four to three days increased the readmission rate from .090 to .136 (51.1 percent).

Discussion and conclusions

In this study we estimated the impact of length of stay for psychiatric hospitalizations on readmission rates by using two alternative methods. First, using ordinary least-squares analyses, we found that length of stay and readmission rate were significantly negatively correlated. As noted above, we believe that because of the problem of self-selection, patients who are sicker are more likely to have longer admissions and more readmissions, and thus the ordinary least-squares analyses estimation would have a positive bias. Despite this positive bias, we found a negative impact of length of stay on readmission rate. Thus this method underestimated the impact of length of stay on readmission rate. To address the self-selection bias, we used a two-stage instrumental variable model, and, as predicted, we found that the negative impact of length of stay on readmission rate was even larger. In both models, we found that the effect of length of stay on readmission rate is not linear. Changes in length of stay had a significantly larger impact on readmission rate when length of stay was shorter.

The results of previous studies contradict our findings. Two studies found that patients with multiple admissions had significantly longer stays (16,17). A study by Kessing and colleagues (18) found that patients with affective disorders whose admissions were longer had higher rates of readmission. Another study by Lyons (14) examined predictors of readmission for 255 patients who were admitted to seven different hospitals in a regional managed care program and found no evidence that premature discharge was associated with readmission risk. These studies controlled for severity of illness to various extents, but the source of variation in length of stay was from unobserved factors that are subject to self-selection. The results of these studies are consistent with our argument that estimating with ordinary least-squares analyses gives biased estimations. This bias is explained by the fact that both length of stay and readmission rate are indicators of, or correlated with, the severity of illness.

Previous studies have also postulated that the regulations of managed care plans that decrease length of stay for inpatient treatment of depression could have a negative impact on outcomes. In 1998 Wickizer and Lessler (23) analyzed the effect of shortening length of stay and found that patients whose hospitalizations were restricted by utilization review had higher rates of readmission during the 60 days following discharge. In addition, Heeren and colleagues (6) recently reported a temporary association between decreasing length of stay and increasing readmission rate in a psychogeriatric unit. It should be noted that severity of illness, which is an important source of variation in length of stay, was not a factor in these studies. Variation was attributable to utilization reviews (23) or to when the hospitalization occurred (6), and therefore self-selection played a less important role in the determination of length of stay. When comparing the outcomes of patients that had short or long hospitalizations, it is important to understand what determined the length of stay. The ideal design for causal interpretation is when the length of stay is determined randomly and thus is not correlated with severity of the illness. In nonexperimental, natural settings one of the major determinants of length of stay is the severity of the illness, not external factors, such as utilization reviews, changes in hospital policies over time, or randomization of patients into groups. Therefore, it is very likely that the patients who stay longer are sicker. This produces the most biased results. We believe that in two studies (6,23) the results were less likely to be biased, because the determination of hospitalization stay was due to specific external reasons that were less likely to be correlated with severity of the illness (that is, utilization reviews or changes in the targeted length of stay over the time of the study, which could be due to managed care or hospital policies). In other words, patients who stayed longer did so, at least in part, because of external reasons (that is, less strict review practices or being hospitalized in a year when all hospitalizations were longer) and not necessarily because they were sicker.

The mechanisms by which longer inpatient stays reduce the readmission rate are beyond the scope of this study. Patients who are allowed to have longer stays are likely to be more stable at the time of discharge, to be better engaged, and to be more likely to follow up with outpatient care. The specific mediators of the effect of length of stay on readmission rate need to be further studied and eventually be set as goals of inpatient psychiatric treatment, regardless of how these mediators would affect the length of stay. Stabilizing the patient and having appropriate discharge planning before discharge are already well-known goals of inpatient treatment teams, and it is possible that we found a sharp increase in the readmission rate among patients with shorter stays because excessively short stays—that is, less than four or five days—make these goals unlikely to be accomplished successfully.

Our study has several limitations. Administrative observational data are subject to certain inherent limitations. Even though we believe that using the instrumental variable method could give us a better estimate of the impact of length of stay on readmission rate than has been previously reported, our calculations are subject to assumptions and do not replace being able to randomly assign persons to groups that have longer or shorter stays. If the mean length of stay at a hospital (identified by zip code) was correlated with other unobserved variables that were themselves correlated with higher readmission rates, our estimations would be biased. Because a higher mean length of stay can result from greater severity of illness or drug and alcohol dependence in the area, we determined whether any correlation existed between these possible sources of bias and the mean length of stay in a particular hospital (identified by zip code) and found none. The actual source of bias would be the unobserved variables—severity of illness or substance dependence—which we could not test for. However, the fact that the observed severity indicators were not correlated with the mean length of stay is encouraging.

A further limitation intrinsic to administrative data analyses is the lack of direct clinical assessments of the outcomes. Inpatient readmissions are a common but controversial measure of outcomes in psychiatry (4,10). We argue that a readmission is an adverse outcome because of its cost to the providers, patients, and society and because it shows that other less restrictive treatments have failed or that the safety of the patient is at risk (11,12). We believe that the controversy about the use of readmission rate and other outcome measures that are related to service use is due, in part, to studies that have tested the utility of readmission rates without addressing the problem of self-selection (14). We also agree that readmission rate or other use of services would not be a good outcome measurement if the problem of self-selection as a factor in the variation of length of stay were not addressed. Finally, although the data were drawn from hospitals across the United States, the sampling strategy was not designed to produce nationally representative estimates. It is possible that the association between length of stay and readmission rate found in this study is not be generalizable to all hospitals.

In summary, the continuous decrease in length of stay for inpatient psychiatric treatment could be deleteriously affecting outcomes of treatments for psychiatric disorders, and studies that do not address the problem of self-selection are misleading. Further studies that use different data sets and different instrumental variables are necessary to better identify the impact of length of stay on readmission rates.

Dr. Figueroa is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, 130 West Kingsbridge Road, 00MH, Bronx, New York 10468 (e-mail, [email protected]) and with the H. John Heinz III School of Public Policy and Management at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. Dr. Harman is with the department of health services administration at the College of Public Health and Health Professions in the University of Florida in Gainesville. Dr. Engberg is with RAND in Pittsburgh.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of psychiatric hospitalizations by diagnostic group for 5,735 patients who had one or more discharges with a primary psychiatric diagnosis in 1997 and 1998

|

Table 2. Results of first-stage regression analysis to predict determinants of length of psychiatric hospitalizations for 5,735 patients who had one or more discharges with a primary psychiatric diagnosis in 1997 and 1998

|

Table 3. Results of second-stage regression analysis to predict determinants of readmission rates for inpatient psychiatric treatment for 5,735 patients who had one or more discharges with a primary psychiatric diagnosis in 1997 and 1998

1. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R: Costs and use of mental health services before and after managed care. Health Affairs 17 (2):40–52, 1998Google Scholar

2. Leslie DL, Rosenheck R: Shifting to outpatient care? Mental health care use and cost under private insurance. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1250–1257, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Pincus HA, Zarin DA, West JC: Peering into the 'black box'. Measuring outcomes of managed care. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:870–877, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lieberman PB, Wiitala SA, Elliott B, et al: Decreasing length of stay: are there effects on outcomes of psychiatric hospitalization? American Journal of Psychiatry 155:905–909, 1998Google Scholar

5. Merrick EL: Treatment of major depression before and after implementation of a behavioral health carve-out plan. Psychiatric Services 49:1563–1567, 1998Link, Google Scholar

6. Heeren O, Dixon L, Gavirneni S, et al: The association between decreasing length of stay and readmission rate on a psychogeriatric unit. Psychiatric Services 53:76–79, 2002Link, Google Scholar

7. Wickizer TM, Lessler D, Boyd-Wickizer J: Effects of health care cost-containment programs on patterns of care and readmissions among children and adolescents. American Journal of Public Health 89:1353–1358, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wells KB, Schoenbaum M, Unutzer J, et al: Quality of care for primary care patients with depression in managed care. Archives of Family Medicine 8:529–536, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Fortney JC: Variation among VA hospitals in length of stay for treatment of depression. Psychiatric Services 47:608–613, 1996Link, Google Scholar

10. Pridmore S, Hornsby H, Hay D, et al: Survival analysis and readmission in mood disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 165:824–827, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Pottick KJ: Changing patterns of psychiatric inpatient care for children and adolescents in general hospitals, 1988–1995. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1267–1273, 2000Link, Google Scholar

12. Thakur NM, Hoff RA, Druss B, et al: Using recidivism rates as a quality indicator for substance abuse treatment programs. Psychiatric Services 49:1347–1350, 1998Link, Google Scholar

13. Appleby L, Luchins DJ, Desai PN, et al: Length of inpatient stay and recidivism among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 47:985–990, 1996Link, Google Scholar

14. Lyons JS: Predicting readmission to the psychiatric hospital in a managed care environment: implications for quality indicators. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:337–340, 1997Link, Google Scholar

15. Thomas MR, Rosenberg SA, Giese AA, et al: Shortening length of stay without increasing recidivism on a university-affiliated inpatient unit. Psychiatric Services 47:996–998, 1996Link, Google Scholar

16. Geller JL: The effects of public managed care on patterns of intensive use of inpatient psychiatric services. Psychiatric Services 49:327–332, 1998Link, Google Scholar

17. Korkeila JA: Frequently hospitalised psychiatric patients: a study of predictive factors. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:528–534, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Kessing LV, Andersen PK, Mortensen PB: Predictors of recurrence in affective disorder: a case register study. Journal of Affective Disorders 49:101–108, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. McClellan M, McNeil BJ, Newhouse JP: Does more intensive treatment of acute myocardial infarction in the elderly reduce mortality? Analysis using instrumental variables. JAMA 272:859–866, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Newhouse JP, McClellan M: Econometrics in outcomes research: the use of instrumental variables. Annual Review of Public Health 19:17–34, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Duan N: Smearing estimate. Journal of the American Statistical Association 78:605–610, 1983Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Manning WG: The logged dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, and the retransformation problem. Journal of Health Economics 17:283–295, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Wickizer TM, Lessler D: Do treatment restrictions imposed by utilization management increase the likelihood of readmission for psychiatric patients? Medical Care 36:844–850, 1998Google Scholar