The Cost of High-Fidelity Supported Employment Programs for People With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study determined the costs of evidence-based supported employment programs in real-world settings. METHODS: A convenience sample of 12 supported employment programs known to follow closely the principles of evidence-based supported employment was asked to provide detailed information on program costs, use, and staffing. Program fidelity was assessed by using the Supported Employment Fidelity Scale. Cost and utilization data were analyzed in a comparable manner to yield direct and total costs per client served, per full-year-equivalent client, and per employment specialist. RESULTS: Usable data were obtained from seven programs in rural and urban locations in seven states: Indiana, Kansas, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Vermont. All programs received high fidelity ratings, ranging from 70 to the maximum value of 75. Annual direct costs per client served varied from $860 in New Hampshire to $2,723 in Oregon, and direct costs per full-year-equivalent client varied from $1,423 in Massachusetts to $6,793 in Indiana. Direct costs per employment specialist did not show as much variation, ranging from $37,339 in Rhode Island to $49,603 in Massachusetts, with a mean of $44,082. Differences in cost per client arose in part from differences in rules for determining who is or is not considered to be on a program's caseload. By assuming a typical caseload of about 18 clients, it was estimated that the cost per full-year-equivalent client averaged $2,449 per year, ranging from $2,074 to $2,756. CONCLUSIONS: The results point to the need for greater uniformity in caseload measurement and help specify the costs of high-fidelity supported employment programs in real-world settings.

U.S. surveys indicate that between 75 and 90 percent of adults with severe mental illness are unemployed (1,2). However, work in regular settings is widely viewed as an important factor in community integration and recovery (3,4,5,6,7). Competitive employment yields important benefits: it can increase self-esteem (3,4,5), mental health (3), quality of life (3), overall functioning (4), and satisfaction with finances, (4) vocational services (5), and leisure (5). Competitive employment can also reduce psychiatric symptoms (4,5). Many if not all of these benefits appear to emerge primarily from competitive employment and not from sheltered employment (5).

Evidence-based supported employment—also called individual placement and support, or IPS, but referred to in the remainder of this paper simply as supported employment—is a well-documented, standardized approach to helping individuals with severe mental illness find and maintain competitive employment (7,8,9,10,11,12). Supported employment differs from traditional approaches to vocational rehabilitation in that employment specialists help clients to define and find a job that matches their interests and abilities; the search for a job is initiated rapidly; support is maintained as long as necessary; and the employment specialist is integrated with the clinical team (12,13). Several quasi-experimental studies and studies in which clients were randomly assigned to groups indicate that supported employment is much more effective than traditional approaches in helping clients find competitive jobs, lengthening the time spent in such jobs, and increasing income from regular employment (14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23).

Despite strong empirical evidence of the effectiveness of supported employment, access to such programs remains limited. A recent survey conducted among members of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill found that only 28 percent of consumer members had received any form of supported employment services; 23 percent received these types of employment services in the past year (24). Previous surveys have found even lower rates of access (25,26,27).

Several factors account for the sparse implementation of supported employment programs: the rigid funding rules of the vocational rehabilitation system, lack of coverage by Medicaid, lack of leadership by program administrators, resistance to change of clinicians and supervisors, and inadequately informed clients and relatives (2). Funding for these programs is likely to be insufficient, partly because of the perception that supported employment services are too expensive.

Relatively little is known about the costs of supported employment programs, particularly of high-fidelity programs in real-world settings. To date only two economic analyses have reported costs for supported employment programs. In an early study, two day treatment programs that were converted into supported employment programs had yearly per client costs of $1,760 and $1,880 after the conversion (28). In a subsequent study of clients who were randomly assigned to groups, the supported employment program had an annual cost of $3,800 per client (29). However, cost estimates from research demonstrations such as these are influenced by many factors that do not apply in real-world settings: newly hired staff, unusually careful training and supervision, clients who cannot be rejected or dropped, the influence of research funding on wages, and so on. Reflecting the uncertainty about the costs of supported employment services, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recently estimated that the "direct cost of vocational services was $2,000 to $8,000 per person [per year]" (30).

Moreover, economic analyses suggest that only if supported employment programs replace existing programs are supported employment programs likely to be cost-neutral or cost-saving (31,32). Clearly, this replacement will not be possible in all settings. Thus little is now known about how much supported employment programs are likely to cost in real-world settings. In particular, the costs of programs that have achieved high fidelity to the supported employment model are likely to be of interest to program planners. The purpose of this exploratory survey was to gain some indication of these costs.

Methods

Identification of programs

Our strategy was to identify a sample of high-fidelity programs from various U.S. regions that operated in real-world settings and then to obtain detailed cost and caseload information from each program so as to be able to relate caseload to costs. A convenience sample of 12 agencies known, on the basis of earlier personal contact with one or more of the authors, to have high-fidelity supported employment programs were invited to participate. Demonstration programs involved in a research study were excluded.

Data

Each program was asked to provide three kinds of data: information on program staffing, organization, and services that would be sufficient to rate the program on the Supported Employment Fidelity Scale, formerly called the Individual Placement and Support Model Fidelity Scale (11,33); statements of expenditures for fiscal year 2001; and utilization data, dates that individuals began and ended any supported employment services during that time. Fidelity was rated by means of an interview with the program director, which was conducted by one of the authors: DB, GB, or RD, depending on the program. Statements of expenditures, with clarifications as needed, were obtained from the program's financial officer, or in one case from the agency director. Program supervisors or information systems personnel provided utilization data and aided in their interpretation.

Analysis of expenditures

Data on program expenditures were reviewed by an economist (EL) and an experienced program business officer (PB). We attempted to make expenditure amounts comparable across sites. Costs were reclassified as either direct or indirect—that is, overhead—in as uniform a manner as possible. Also, for comparability, occupancy costs were imputed on the basis of the number of square feet occupied by supported employment staff and median office rental costs in the state (34). Overhead costs were allocated in proportion to the direct costs of each program. Costs provided for two sites—Indiana and New Hampshire—were for fiscal year 2002 and were deflated to 2001 dollars by using the June-to-June Consumer Price Index. (Details on the adjustment methods are available from the authors.)

Analysis of utilization data

Start and end dates were used to calculate the number of clients who received any services as well as the number of full-year-equivalent clients. The number of full-year-equivalent clients was calculated analogously to the number of full-time equivalent personnel in a program and is equivalent to the average caseload size during the year.

Results

We were able to obtain useable information from seven of the 12 programs that we contacted: four programs located in New England—Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island—and three others located in the Midwest and the West—Indiana, Kansas, and Oregon. We were unsuccessful in obtaining usable information from five programs located in four additional states. Data on client participation in a Denver, Colorado, program were not recorded in a manner that allowed for computation of the number of clients served. The other programs—two in New Jersey, one in Washington State, and one in South Carolina—either did not respond to repeated requests for data or did not provide sufficient data.

All programs included in our study are in urban areas except for two—the Oregon and Vermont programs. Three programs serve counties with significant black and Hispanic populations—the Massachusetts and Indiana programs serve a population that is more than 20 percent black and Hispanic population combined, and the Rhode Island program serves one that is more than 15 percent black and Hispanic combined, whereas the other four programs have small or insignificant minority populations.

The seven programs included in the study received fidelity ratings that ranged from 70 to 75, with a mean of 72.7. Thus all programs had similar fidelity ratings, at or near the maximum value of 75. Ratings from 66 to 75 are considered to reflect good implementation. All programs had been in existence for at least one year in fiscal year 2001.

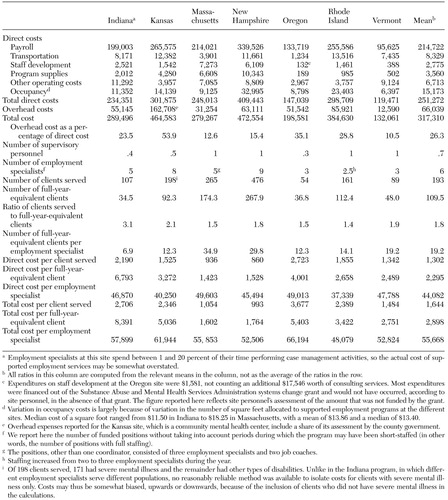

Cost data obtained from the seven programs are shown in Table 1. Total direct costs varied more than threefold, from $119,471 at the Vermont site to $409,443 at the New Hampshire site. The Vermont site served only 89 clients, compared with 476 clients at the New Hampshire site.

In this small sample of programs we found a more than threefold variation in direct cost per client served—from $860 in New Hampshire to $2,723 in Oregon—and an almost five-fold variation in direct cost per full-year-equivalent client—from $1,423 in Massachusetts to $6,793 in Indiana. The variation in client turnover rate amplified the variation in cost per client served, which made the variation in cost per full-year-equivalent client larger than the variation in cost per client served.

Direct costs per employment specialist are the most uniform measure of cost, ranging from $37,339 in Rhode Island to $49,603 in Massachusetts, with a mean of $44,082 and a median of $46,870. Total costs per employment specialist varied more than direct costs, because of the variation in overhead rates across sites.

Table 1 also presents the ratio of full-year-equivalent clients to employment specialists. These ratios exhibit a wide range, from 6.9 in Indiana to 34.9 in Massachusetts.

Discussion and conclusions

Variability in cost per client served and cost per full-year-equivalent client was larger than we anticipated. Variability in cost per client served can be attributed in part to variability in the rate of client turnover: a higher rate of turnover, evidenced by a larger ratio of clients served to full-year-equivalent clients, increases the number of clients who can receive services at some point during the year and thus reduces the cost per client served. Even in this small sample of high-fidelity programs, we found more than a twofold variation in turnover rates.

The Indiana site reported by far the shortest service episodes—103 days, compared with 173 to 254 days for the other sites—and had the highest percentage of clients who reported two episodes (16 percent, or 17 of 107 clients). Only two other sites reported clients having two episodes: seven of 265 clients (3 percent) at the Massachusetts site and four of 161 clients (2 percent) at the Rhode Island site. According to the program supervisor in Indiana, supported employment clients tend to make a quick transition to the treatment teams from which they are simultaneously receiving services. One reason for this rapid transition is that a record of quick successful closures encourages additional referrals from the vocational rehabilitation system.

The effects on outcomes of a policy of rapid closures are unclear. In practice, employment specialists typically work more closely with some clients than others at any given time: some clients may be working and need minimal support, which can be given by a case manager, other clients may go through periods during which they appear less interested in seeking work. In both cases, clients either can officially be kept on an employment specialist's caseload or their case can be considered closed, possibly on a temporary basis, without this closure having a material impact on the client. If the employment specialist remains part of the client's clinical team, as is the case at the Indiana site, so that a client can quickly resume employment services when needed, the principle of time-unlimited services is maintained. This variation in case closure practice across sites may help explain the large variation in direct cost per full-year-equivalent client across sites. Programs with lower numbers of full-year-equivalent clients may be counting as clients only individuals with whom they are working actively at any given time.

Costs per employment specialist, in contrast, were relatively uniform from site to site. Indeed, this relative uniformity in cost per employment specialist can be used to infer what a supported employment program is likely to cost. In the Supported Employment Fidelity Scale, the caseload per employment specialist can reach 25 before fidelity is compromised. However, the average caseload in our sample was 19, and a previous survey of 32 supported employment programs that were based in community mental health centers found an employment specialist's caseload to average 16 (35). If we then assume a typical caseload of 18 and combine this caseload with the average cost per employment specialist of $44,082, we obtain a cost of $2,449 per full-year-equivalent client per year, with a range from $2,074 to $2,756, on the basis of the range of costs per employment specialist.

As for the cost per client served, programs in our sample had on average 1.8 times as many clients served as full-year-equivalent clients. Thus the average annual cost per client served, still assuming a ratio of 18 full-year-equivalent clients per employment specialist, becomes $1,361, ranging from $1,152 to $1,531.

Overhead increases all these costs by about 15 to 30 percent. Although the introduction of a supported employment program into the programming of a community mental health center or rehabilitation agency would not actually increase the organization's costs by that entire amount, some billing and clerical costs that are classified here as overhead would increase directly with the volume of clients.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the small convenience sample may not be representative. Second, some of the variation in costs that we report certainly results from differences in accounting practices across sites, despite our attempts to adjust for such differences. Yet another limitation lies in our not taking into account the interrelation between supported employment services and the costs of case management services. At the Indiana site, for example, employment specialists spent a small part of their time providing case management services; therefore, the costs of supported employment services at that site may be somewhat overstated. Fourth, we have not attempted to evaluate the outcomes achieved by these different programs.

Finally, this study did not attempt to provide comparative information on the costs of alternative types of vocational rehabilitation programs. Information on costs of alternative programs for persons with mental illness is limited (36). An important cost advantage of supported employment services is that they quickly adjust to clients' evolving needs and interests, whereas the costs of day treatment and sheltered programs are less easily adjusted. The evidence to date, although not yet conclusive, suggests that supported employment is more cost-effective than alternative programs in terms of outcomes of regular employment and community integration (36).

Implications

The findings of this study have at least three practical implications. First, greater uniformity in the measurement of caseload size is desirable. Caseload size is an important component of supported employment program fidelity. To promote continuity of care and flexibility in service delivery, clients should be counted on a caseload for a longer time rather than a shorter time. Funders could provide incentives that encourage inclusion in the caseload for a reasonable amount of time rather than rapid closure.

Second, the cost estimates generated from this survey may be of use both to service providers who are contemplating the development of supported employment services and to state governments or other insurers who are seeking to set appropriate reimbursement levels for supported employment services. Vocational rehabilitation occupies a place of central importance in the life of persons with severe mental illness, and the efficacy of supported employment is now well-documented. In view also of the costs of second-generation antipsychotic medications and of other routinely provided services, the costs of supported employment seem surprisingly modest.

Finally, studies such as this one may be helpful in estimating the cost of other evidence-based practices, such as assertive community treatment or integrated treatment for dual disorders. As noted earlier, costs derived from research demonstrations tend to overstate the costs of real-world programs. Costs derived from an unselected sample of real-world programs, in contrast, tend to understate the costs of high-fidelity programs, because higher fidelity usually comes at a price. Assessing costs in mature, high-fidelity, real-world programs should be of considerable help to mental health program planners.

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Johnson & Johnson World Contributions Program, the MacArthur Foundation, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the West Foundation. The first author also thanks the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (Québec Health Research Fund) for a senior investigator award.

Dr. Latimer is affiliated with the Douglas Hospital Research Centre, 6875 LaSalle Boulevard, Verdun, Quebec, Canada H4H 1R3 (e-mail, [email protected]) and with the department of psychiatry at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec. Mr. Bush, Ms. Becker, and Dr. Drake are with New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center in Dartmouth. Dr. Bond is with the department of psychology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

|

Table 1. Costs of seven supported employment programs in fiscal year 2001 dollars

1. Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Mueser P: A prospective analysis of work in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:281–296, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services 52:313–322, 2001Link, Google Scholar

3. VanDongen C: Quality of life and self-esteem in working and nonworking persons with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 32:535–548, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mueser KT, Becker DR, Torrey WC, et al: Work and nonvocational domains of functioning in persons with severe mental illness: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 185:419–426, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bond G, Resnick S, Drake R, et al: Does competitive employment improve nonvocational outcomes for people with severe mental illness? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 69:489–501, 2001Google Scholar

6. Provencher H, Greg R, Mead S, et al: The role of work in the recovery of persons with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 26:132–144, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Becker DR, Drake RE: A Working Life for People With Severe Mental Illness. New York, Oxford University Press, 2003Google Scholar

8. Becker D, Drake R: Individual placement and support: a community mental health center approach to vocational rehabilitation. Community Mental Health Journal 30:193–206, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Drake RE: A brief history of the individual placement and support model. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:3–7, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, et al: An update on supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:335–346, 1997Link, Google Scholar

11. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: A fidelity scale for the individual placement and support model of supported employment. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 40:265–284, 1997Google Scholar

12. Bond G: Principles of the individual placement and support model: empirical support. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:11–23, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Becker D, Drake R: A Working Life: The Individual Placement and Support Program (IPS). Concord, NH, New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, 1993Google Scholar

14. Bond GR, Dietzen LL, McGrew JH, et al: Accelerating entry into supported employment for persons with severe psychiatric disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology 40:75–94, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Becker DR, Bond GR, McCarthy D, et al: Converting day treatment centers to supported employment programs in Rhode Island. Psychiatric Services 52:351–357, 2001Link, Google Scholar

16. Drake RE, Becker DR, Biesanz JC, et al: Rehabilitative day treatment vs supported employment: I. vocational outcomes. Community Mental Health Journal 30:519–531, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Becker DR, et al: The New Hampshire study of supported employment for people with severe mental illness: vocational outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:391–399, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Drake R, Becker D, Biesanz JC, et al: Day treatment vs supported employment for persons with severe mental illness: a replication study. Psychiatric Services 47:1125–1127, 1996Link, Google Scholar

19. Drake RE, McHugo G, Bebout R, et al: A randomized clinical trial of supported employment for inner-city patients with severe mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:627–633, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Gervey R, Bedell J: Supported employment in vocational rehabilitation, in Psychological Assessment and Treatment of Persons With Severe Mental Disorders. Edited by Bedell J. Washington, DC, Taylor & Francis, 1994Google Scholar

21. Lehman AF, Goldberg R, Dixon LB, et al: Improving employment outcomes for persons with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:165–172, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Mueser KT, Clark RE, Haines M, et al: The Hartford study of supported employment for persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, in pressGoogle Scholar

23. Meisler N, Williams O, Kelleher J, et al: Rural-based supported employment approaches: results from South Carolina site of the Employment Intervention Demonstration Project. Presented at the 4th Biennial Research Seminar on Work, Matrix Research Institute, Philadelphia, Penn, Oct 12–13, 2000Google Scholar

24. National Consumer and Family Member Survey. National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 2003Google Scholar

25. Five-State Feasibility Study on State Mental Health Agency Performance Measures: Draft Executive Summary. Alexandria, Va, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute Inc, 1998Google Scholar

26. Lehman A, Steinwachs D: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11–23, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Hollingsworth E, Sweeney J: Mental health expenditures for services for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:485–490, 1997Link, Google Scholar

28. Clark RE, Bush PW, Becker DR, et al: A cost-effectiveness comparison of supported employment and rehabilitative day treatment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 24:63–77, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Clark RE, Xie H, Becker DR, et al: Benefits and costs of supported employment from three perspectives. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 25:22–34, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Supported Employment: A Guide for Mental Health Planning and Advisory Councils. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, 2003Google Scholar

31. Clark RE: Supported employment and managed care: can they coexist? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:62–68, 1998Google Scholar

32. Latimer EA: Economic impacts of supported employment for the severely mentally ill. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 46:496–505, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Individual Placement Scale Model Fidelity Scale. New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Centre. Available at www.dartmouth.edu/dms/psychrc/pdf_files/IPSFidelityScale.pdfGoogle Scholar

34. Loopnet: Dataset of state-by-state median cost per square foot for lease of office buildings, 2002–2003. Available at www.loopnet.comGoogle Scholar

35. Bond G, Picone J, Mauer B, et al: The Quality of Supported Employment Implementation Scale. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 14:201–212, 2000Google Scholar

36. Schneider J: Is supported employment cost-effective? A review. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation 7:145–156, 2003Google Scholar