Sexual and Reproductive Behaviors Among Persons With Mental Illness

Abstract

For this study, 200 women and men with a major mood disorder or schizophrenia were interviewed about their sexual and reproductive behaviors. The responses of the women and men were compared with those of persons from a national health survey who were matched for age and race. Compared with women from the national survey, women with mental illness had fewer pregnancies and live births but were more likely to have had a pregnancy that did not result in a live birth. Women with mental illness had more lifetime sexual partners. The findings suggest that clinicians should pay attention to patients' sexual and reproductive health.

Little information is available about the sexual and reproductive behaviors of persons with mental illness, despite the importance of such behaviors in determining social and emotional well-being. These behaviors also affect the need for health care services that are focused on sexually transmitted diseases, family planning, and childbearing (1,2,3).

Some evidence suggests that, compared with women without mental illness, women with schizophrenia are less likely to have a current sexual partner and are more likely to have a higher number of lifetime sexual partners and unwanted pregnancies (4). Most studies have found that women with schizophrenia have reduced fertility compared with women in the general population (4,5,6). The sexual and reproductive behaviors of women who have mood disorders have not been the focus of much systematic investigation.

Our study compared the sexual and reproductive behaviors reported by women and men who have mental illness with those by matched comparison groups from the general population. Also, within our study sample, we compared responses of individuals with schizophrenia and responses of those with a major mood disorder.

Methods

Participants were recruited from two outpatient psychiatric centers (one in an urban area and one in a suburban area) in the Baltimore region from March to December 2000 for a study about health behaviors among persons with mental illness (7). The sample was selected to enroll 100 individuals with schizophrenia and 100 individuals with a major mood disorder. A total of 200 of 275 eligible individuals (73 percent) provided written informed consent and completed an interview that included items about sexual and reproductive behaviors from the Third National Health and Examination Survey (NHANES III) (8), a survey that collects data from a representative sample of the U.S. population. Our study was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the Sheppard Pratt Health System.

To compare responses from our sample with those from the general U.S. population, we selected comparison groups of women and men from the NHANES III data set (9) that were matched to study participants by age (within three years) and race. In most cases, 15 matches from NHANES III were found per study participant. Nine participants who were of Asian or Pacific-Islander or Native-American ethnicity could not be matched and were excluded from analyses. Responses from the study sample were compared with those from the NHANES III group by t test for continuous variables or by Mann-Whitney rank sum test for variables that had skewed distributions. Chi square tests were used for dichotomous variables. Correlation of outcomes across participants caused by common age or race classification was minimal; thus matched analysis results were nearly the same as unmatched analysis results.

To compare the responses from the schizophrenia and mood disorder groups, regression analyses were performed on each outcome variable by gender. In addition to diagnosis, variables included were race (Caucasian versus non-Caucasian), education (graduated from high school versus having less than a high school education), site (suburban versus urban), and age. Linear regression was used for continuous outcome variables, logistic regression for dichotomous variables, and negative binomial models for count variables.

Results

The study sample consisted of 191 men and women with schizophrenia or a mood disorder. The study sample included 100 women with a mean±SD age of 45.1±9.6 years. Sixty-one percent (N=61) were Caucasian, 73 percent (N=73) were high school graduates, 64 percent (N=64) had been given a diagnosis of mood disorder, and 36 percent (N=36) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The 91 men in the sample had a mean age of 42.7±8.1. Fifty-six percent (N=51) were Caucasian, 72 percent (N=65) were high school graduates, 33 percent (N=30) had been given a diagnosis of a major mood disorder, and 67 percent (N=61) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The educational level of the women and men in our sample did not differ significantly from that of the individuals who were matched from the NHANES III.

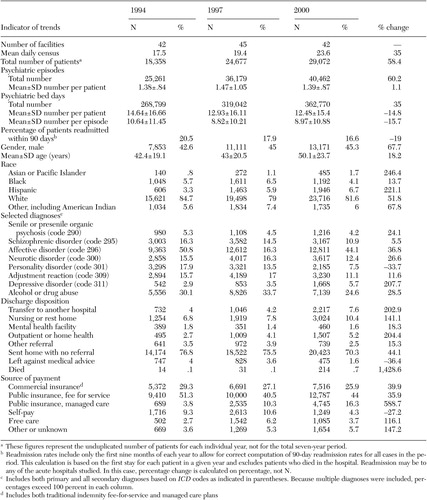

As shown in Table 1, both the women and men in our sample were significantly less likely to ever have been married than those in the respective NHANES III comparison groups. Women with mental illness had more lifetime sexual partners than women in the comparison group; however, this comparison was not significant for men.

Compared with women from the national sample, fewer of the women with mental illness reported ever having been pregnant, and they reported having fewer pregnancies and live births. However, the proportion of women who had had a pregnancy that did not result in a live birth was significantly higher in the group with mental illness. No significant differences were found between the two groups of women in reported age at the time of first sexual intercourse or first live birth or in the proportion who had ever taken birth control pills.

Regression analyses within the study sample indicated that men who had been given a diagnosis of a mood disorder reported significantly more lifetime sexual partners than those who had been given a diagnosis of schizophrenia (incident rate ratio=2.54, 95 percent confidence interval=1.22, 5.26, p=.012). Diagnosis did not predict other outcomes when the analysis controlled for race, education, site, and age.

Discussion and conclusions

Our findings suggest gender differences in sexual behaviors among persons with mental illness. The women with mental illness, but not the men, reported having more partners than the comparison group. This finding may reflect the relatively chaotic pattern of sexual relationships and the high rate of nonconsensual sex that has been observed among women with mental illness (2,4). Our results highlight the need to prevent sexually transmitted diseases and victimization in this group.

The women with mental illness had fewer live births and were less likely to have been pregnant than women from the comparison group. These findings are consistent with those of some, but not all, studies indicating reduced childbearing among women with schizophrenia (4,5,6). Reduced pregnancy and childbearing may be related to the lower rate of marriage that we found in our sample or to the effects of psychotropic medications and the symptoms of psychiatric illness (5). Our study adds to the literature because of its consideration of a representative sample of outpatients in psychiatric treatment and the inclusion of women with major mood disorders.

The observation that women with mental illness were more likely than women in the comparison group to have a pregnancy that did not result in a live birth has not been previously reported. This finding is particularly striking given the lower number of pregnancies in the group with mental illness. We do not know whether the pregnancy losses were due to therapeutic abortions or spontaneous miscarriages. This issue merits further investigation.

Although a history of pregnancy was less common among women with mental illness, 75 percent of these women had been pregnant. Information was not available about the women's psychiatric status at the time of pregnancy, but we assume that many experienced psychiatric illness during their reproductive years. These results underscore the need for gynecologic and obstetric services for women with mental illness that promote healthy sexuality and that address the added problems of psychiatric symptoms and treatment.

Although the study sample and the comparison group were matched on demographic characteristics, our findings should be interpreted with caution given that the sample of persons with mental illness was drawn from two centers in one region and the NHANES III data set was from a national sample.

The sexual behaviors of persons with serious mental illness have implications for their emotional and physical well-being. Clinicians should pay attention to the sexual and reproductive health needs of persons with mental illness.

Dr. Dickerson is affiliated with the Stanley Research Center at Sheppard Pratt Health System, 6501 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21204 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Kreyenbuhl, Dr. Goldberg, Dr. Fang, and Dr. Dixon are with the department of psychiatry and Dr. Brown is with the department of epidemiology at the University of Maryland in Baltimore.

|

Table 1. Responses of women and men with mental illness and matched samples from the Third National Health and Nutrition ExaminationSurvey (NHANES III)

1. Cournos F, Guido JR, Coomaraswamy S, et al: Sexual activity and risk of HIV infection among patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:228–232, 1994Link, Google Scholar

2. Carey MP, Carey KB, Kalichman SC: Risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among persons with severe mental illnesses. Clinical Psychology Review 17:271–291, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Miller LJ: Sexuality, reproduction, and family planning in women with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:623–635, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Miller LJ, Finnerty M: Sexuality, pregnancy, and childrearing among women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services 47:502–506, 1996Link, Google Scholar

5. Nimgaonkar VL, Ward SE, Agarde H, et al: Fertility in schizophrenia: results from a contemporary US cohort. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 95:364–369, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Haukka J, Suvisaari J, Lonnqvist J: Fertility of patient with schizophrenia, their siblings, and the general population: a cohort study from 1950–1959 in Finland. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:460–463, 2003Link, Google Scholar

7. Dickerson FB, McNary SW, Brown CH, et al: Somatic healthcare utilization among adults with serious mental illness who are receiving community psychiatric services. Medical Care 4:560–570, 2003Google Scholar

8. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III, 1988–1994. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services. National Center for Health Statistics, 1996Google Scholar

9. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: NHANES III Data Files. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, March 2002. Available at www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/datalink.htmGoogle Scholar