Use of Self-Help Services and Consumer Satisfaction With Professional Mental Health Services

Abstract

This study tested the hypothesis that users of mental health self-help services would be more satisfied with professional mental health services than clients who did not use self-help services. A survey was administered to 311 clients of professional mental health services, 151 (49 percent) of whom were users of self-help services. A multiple regression model showed that the use of self-help services was associated with greater satisfaction with professional mental health services. This finding provides support for the idea that the use of self-help services encourages appropriate use of professional services. The study provided evidence that self-help and traditional mental health services can function complementarily rather than in competition with one another.

Mental health self-help services, which are increasingly prevalent, are associated with positive outcomes and are cost-effective (1,2). As a result of the service and cost constraints of managed care in the public mental health sector, self-help services are essentially providing the "spillover" assistance that the formal sector does not have the time or the money to provide (3). However, negative attitudes toward self-help services persist among mental health professionals, including a lack of awareness of self-help services, fears that self-help services encourage discontinuation of professional services, assertions that self-help centers do not provide positive outcomes—that is, adopting a competitive stance toward another service sector—and a reluctance on the part of professionals to undertake the necessary work to build a cohesive service system that includes self-help services (4,5,6).

Although self-help services may be viewed as a threat to the formal service delivery system, they can also be seen as a resource. To be considered as a resource, self-help services need to demonstrate that they enhance rather than detract from the delivery of professional mental health services. One way in which self-help services might benefit professional services is through an increase in consumer satisfaction with professional services.

In this study we examined the relationship between whether clients used self-help services and their level of satisfaction with formal mental health services, given that satisfaction is a crucial element of positive mental health outcomes (7). On the basis of previous work by one of the authors (3), we believed that greater engagement in self-help services would be associated with greater satisfaction with professional mental health services.

Methods

To compare users and nonusers of self-help services, we identified a purposive sample of 311 persons, stratified to match the general demographic pattern of the state of Missouri. All participants were involved in mental health services, and about half were also involved in self-help services, including formal self-help agencies, more loosely structured self-help groups, clubhouses, and peer-support groups. Users and nonusers of self-help services were recruited during a two-month period at community or organizational meetings or in mental health centers. A total of 260 participants (85 percent) were Caucasian, 222 (71 percent) were between the ages of 22 and 50 years, 242 (80 percent) were unmarried (single or divorced), 200 (65 percent) had a high school education or less, and 224 (75 percent) had an annual income of less than $8,000. The study was conducted from January to June 2002.

A panel of experts comprising consumers, researchers, and advocates for persons with mental illnesses developed a 25-item written questionnaire that was used to collect data for this study. Items on the questionnaire addressed demographic characteristics, whether the respondent was a member of a self-help group, and scores on the eight-item Client Satisfaction Scale (CSQ-8) (8). The CSQ-8 was selected because it is simply worded, easily understood, and widely applicable. It was also chosen for its technical qualities (31): it is normed and has good construct validity as well as excellent internal consistency (alphas of .86 to .94). In this sample, the internal consistency was excellent as well (alpha=.93).

The study was approved by the University of Missouri's institutional review board. After obtaining written informed consent from all participants, trained data collectors, most of whom were fellow consumers, administered questionnaires to individuals or small groups. A high response rate (94 percent) was obtained; of 331 persons approached, only 20 refused to participate. Multiple regression analysis was used to explore the extent to which participation in self-help groups accounted for variance in the overall rating of client satisfaction with professional services.

Results

A total of 151 study participants (49 percent) participated in self-help services. No significant differences were observed in mean±SD satisfaction scores between users and nonusers of self-help services (4.28±.895 and 4.15±1.11, respectively; possible scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction). However, multiple regression analysis was used to identify associations between use of self-help services and satisfaction with professional mental health services.

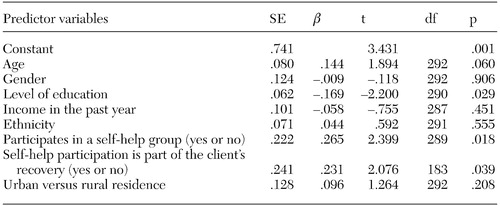

On the basis of the literature on factors associated with consumer satisfaction and use of self-help services (7,9), predictor variables entered into the model were age, gender, level of education, income, ethnicity, urban versus rural location, participation in self-help services, and agreement with the statement that self-help services are essential to recovery. The model is summarized in Table 1. Overall, the model was significant (R2=.087, F=2.012, df=8, 169, p=.048) but explained very little of the overall variance in service satisfaction scores. When demographic factors were controlled for, lower levels of education, use of self-help services, and agreement that self-help services are essential to recovery were associated with greater satisfaction with professional mental health services.

Discussion

Our hypothesis that there would be an association between use of self-help services and satisfaction with professional services was conditionally supported: self-help participation was a significant predictor of satisfaction with professional services when other factors were controlled for in the regression. Use of self-help services and the perception that self-help is essential to the consumer's recovery were also associated with greater satisfaction with professional services, which seems especially salient in light of the known importance of involvement in self-help services. Equally important was the finding that the degree to which users of self-help services believe that such services complement their efforts toward recovery has a positive association with their mental health service satisfaction ratings. Some mental health professionals have expressed the fear that the use of self-help services detracts from the use and efficacy of professional mental health services. However, the results of this study suggest that professional and consumer providers can collaborate to deliver the most effective and most consumer-oriented services, particularly when each provider is aware of the services that the other provides.

It should be noted that this was a cross-sectional, correlational study and thus had the limitations inherent in such methodology. Furthermore, nearly 90 percent of the variance in service satisfaction scores was unexplained by our model. Another limitation was the diversity in the definition of "self-help." In this study, self-help services included formal self-help agencies, more loosely structured self-help groups, clubhouses, and peer-support groups. Because consumer-operated services differ widely in their organizational structure, helping mechanisms, and outcomes, the association between use of self-help services and clients' satisfaction with professional mental health services may have involved a combination of several effects covered by the term "self-help." Finally, random sampling was difficult because of issues of confidentiality of mental health records. Thus the external validity of this study was somewhat limited by our stratified and purposive sampling strategy.

Conclusions

Our data provide evidence that the use of self-help services enhances consumers' satisfaction with traditional mental health services. With this evidence, we believe that if collaboration is already occurring at the consumer level, it is time for conscious collaboration with intent at the administrative levels of both traditional and consumer-operated service organizations. Future studies should address the structures of traditional and consumer-operated services to move the burden of collaboration from consumers to organizations themselves.

Researchers have highlighted the fact that traditional mental health agencies and consumer-operated organizations can collaborate through referrals, coordination, coalition, and joint ventures (10). At the consumer level, the findings of our study suggest that collaboration on referrals is taking place, if only in a de facto sense. Future research seems warranted that focuses on determining the extent to which coordination, coalition, and joint venture aspects of collaboration occur between community mental health agencies and self-help agencies.

Acknowledgment

This research was financially supported by the Missouri chapter of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, Missouri Protection and Advocacy Services, and the University of Missouri, Columbia.

Dr. Hodges and Dr. Markward are affiliated with the University of Missouri, Columbia, School of Social Work, 721 Clark Hall, Columbia, Missouri 65211 (e-mail, [email protected]). Ms. Keele is with the Missouri chapter of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill in Jefferson City. Dr. Evans is with the Missouri Institute of Mental Health in St. Louis.

|

Table 1. Factors associated with satisfaction with professional mental health services among 311 clients participating in a study of use of self-help services

1. Beggs M, Walker EB: Clients serving clients: mental health client self-help projects in Northern California. San Francisco, Zellerbach Family Fund, 1988Google Scholar

2. Hodges JQ, Segal SP: Goal advancement among mental health self-help agency members. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 26:79–85, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Segal SP, Hodges JQ, Hardiman ER: Factors in decisions to seek help from self-help and co-located community mental health agencies. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 72:241–249, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Long L, Van Tosh L: Program descriptions of consumer-run programs for homeless people with mental illness. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1988Google Scholar

5. Lee DT: Professional underutilization of Recovery, Inc. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19:63–70, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Levy LH: Self-help groups viewed by mental health professionals: a survey and comments. American Journal of Community Psychology 6:305–313, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Campbell J: Exemplary practices for measuring consumer satisfaction: a review of the literature, parts 1, 2, and 3. Missouri Institute of Mental Health, Policy Information Exchange. Available at www.mimh.edu/mimhweb/pie/database/getarticle.asp?value =1602, 1999Google Scholar

8. Attkisson CC: Client satisfaction questionnaire (CSQ-8), in Measures for Clinical Practice: A Sourcebook, vol 2, 3rd ed. Edited by Corcoran K, Fischer J. New York, Free Press, 1987Google Scholar

9. Segal SP, Hardiman ER, Hodges JQ: Characteristics of new clients at self-help and community mental health agencies located in geographic proximity. Psychiatric Services 53:1145–1152, 2002Link, Google Scholar

10. Gidron B, Hasenfeld Y: Human service organizations and self-help groups: can they collaborate? Nonprofit Management and Leadership 5:159–172, 1994Google Scholar