Access to and Patterns of Use of Behavioral Health Services Among Children and Adolescents in TennCare

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study assessed trends in access to and use of behavioral health services for school-aged children in TennCare, Tennessee's Medicaid managed care program, between state fiscal years 1995 and 2000. METHODS: Claims, encounter, and enrollment data from the Bureau of TennCare were used. The data analyzed were restricted to services and enrollment periods for children and adolescents between the ages of four and 17 years at the time of service or enrollment. Measures were calculated in four areas: overall access to behavioral health services, use of inpatient services, use of outpatient specialty treatment services, and use of supportive services like case management and medication management. RESULTS: The number of youths who received a behavioral service increased by nearly 50 percent between state fiscal years 1995 and 2000. At the same time, the number of youths enrolled in TennCare increased by 19 percent. The annual access rate increased from 72.7 youths per 1,000 enrollees to 91.7. However, the volume of services for children fell. Access rates were low relative to estimates of need in this population. The system made less use of inpatient services and relied more on outpatient services, particularly case management and medication management services. CONCLUSIONS: Children's access rates for behavioral health services improved even as the TennCare program expanded to cover more children. The system served more youths in part by reducing the volume of services for children receiving treatment and substituting more supportive services. Ongoing performance monitoring for policy making will require enhancements of data monitoring activities by the state.

Consumers, advocates, providers, contractors, and state and federal policy makers are among the groups interested in the issue of monitoring and oversight of behavioral health programs, particularly for vulnerable populations such as children and persons with mental illness. Individual states as well as the health care industry have made many attempts to monitor the quality of health service programs by using such tools as best practice guidelines, report cards, and performance indicators. Whether they are philosophical goals, political symbols, or evidence-based norms, these quality indicators represent an effort to monitor service delivery and serve as models for the improvement of children's health.

Among those attempting to address health care performance systematically is the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). Through its HEDIS (Health Plan Employer Data Information Set) program, NCQA monitors commercial and Medicaid health systems by assessing performance in several domains, including effectiveness of care, access to or availability of care, satisfaction, cost, use, and aspects of health insurance plans, such as stability and its communication activities with plan members (1). Although focused primarily on physical health, HEDIS includes behavioral health measures such as the percentage of members receiving mental health or chemical dependence services, the average length of an inpatient stay, and follow-up after inpatient discharge.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has developed a report card system that provides a more direct focus on behavioral health issues (2). The Children's Mental Health Benchmarking Project (3,4) provides information about children's behavioral health services in state Medicaid programs. The project was able to produce access measures for several states, in the range of 7 to 10 percent of children from birth to the age of 17 years. However, many states could not produce the type of data required for measuring access or other details of service use.

In the study reported here we used a nonexperimental time-series design to describe patterns of use of behavioral health services in the TennCare program's initial six years of operation on the basis of claims, encounter, and enrollment data. TennCare started in January 1994 as a statewide waiver demonstration program, authorized through Section 1115 of the Social Security Act (5), to cover all medical and behavioral health services for youths and adults under a capitated fee structure paid to managed care organizations. In addition to covering all Medicaid-enrolled youths, the program expanded coverage to uninsured and uninsurable persons who did not otherwise qualify for Medicaid or private insurance. In July 1996, through the TennCare Partners Program, Tennessee carved out the behavioral health component to behavioral health organizations to increase the efficiency of treatment. Chang and colleagues (6) documented the problems with respect to behavioral health services in the original TennCare program that led to implementation of the TennCare Partners carve-out.

TennCare has received a great deal of attention in the media and the scientific literature for its once-novel approach to providing capitated insurance coverage to a Medicaid population. Previous studies of TennCare services focused predominantly on medical care for specific types of diseases or services. Researchers have documented service use and outcomes for emergency department care (7,8,9), obstetric and perinatal care (10,11,12), treatment of myocardial infarction (13), treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (14), and use of pharmaceuticals among children with asthma (15).

Several studies have examined TennCare's plan performance—for example, how individuals rate the performance on dimensions such as waiting time and ability to see a specialist—by using enrollee surveys (16,17,18,19). These studies generally showed that TennCare's performance was no worse than that of the preexisting Medicaid program (17) and, although not as good as having private insurance (18), was better than having no insurance (20). Among the competing managed care companies, the plans provided similarly satisfying care for a relatively homogeneous subset of enrollees, although enrollees often rated the bigger managed care organizations better in some areas (16). None of these studies used service use data from the TennCare system to address observed patterns of access and use among children with emotional and behavioral problems.

Hutchinson and Foster (21) provided the most complete review of Medicaid managed behavioral health care. Their review of the literature concluded, with respect to service use outcomes, that managed care improves overall access, reduces use of inpatient services, increases use of case management services, and has ambiguous effects on the use of outpatient services. The bulk of the research involving this population comes from the Massachusetts Medicaid program (22,23); additional results have come from North Carolina (24) and Colorado (25). A General Accounting Office (GAO) study of mental health carve-out programs in four states found similar results for adult populations (26).

The study reported here marks the first state-level, populationwide assessment of behavioral health services based on all sources of TennCare administrative data and is part of an ongoing program of research on Medicaid child and adolescent mental health and substance abuse services (27).

Methods

Data

The data for these analyses come from the Bureau of TennCare's management information system. We received all claims and encounters with a mental health diagnosis (ICD-9 codes 290 to 319) for youths born on or after January 1, 1974, and all enrollment data for youths enrolled between July 1993 and December 2001. For analysis, we restricted the data to include only services and enrollment periods for youths between the ages of four and 17 years at the time of service or enrollment. We also excluded services involving a primary or secondary diagnosis of mental retardation or developmental delay (ICD-9 codes 316 to 319) and services billed through a Medicaid "set-aside" for youths in state custody. We allowed a six-month start-up period for TennCare and up to an 18-month lag in reporting of services so that we report for July 1994 to June 2000, state fiscal years (SFYs) 1995-2000. In addition, we used only paid claims or encounters, which is standard practice for Medicaid analyses.

The Bureau of TennCare receives electronic records of all encounters from the participating managed care organizations and behavioral health organizations contracted to manage physical and behavioral health services for TennCare enrollees. In addition, the bureau maintains its traditional fee-for-service claims processing system for services outside the management responsibility of the managed care organizations and behavioral health organizations. When youths in state custody use services outside the custody service reporting system—meaning the services are financed by the managed care companies—we included their services with the managed care data.

The encounter data consist of two main types of records, corresponding to the types of claim forms used: Uniform Billing—1992 Revision (UB92) records, which are used primarily by hospitals and employ revenue codes defined by the American Hospital Association, and HCFA-1500 records, which are used primarily by individual providers and coded by using the current Procedure terminology system or HCFA Common Procedure Coding System codes. These are the same forms and systems used in the pre-TennCare Medicaid system and in most states that still operate Medicaid on a fee-for-service basis.

Data were transformed into a single record for each day of each type of service, based on an algorithm for assigning service codes to a unique research service category—for example, inpatient services, case management, and family therapy. The "service-day-type" metric has implications for counting services. First, multiple occurrences of the same service type on the same day—for example, two individual therapy sessions—are counted as only one service for that day. However, two different services received on the same day—for example, individual and group therapy—are counted as one day of each type of service, thereby capturing the mix of services received. Second, a 15-minute session counts the same as a 60-minute session—that is, one day for each person. Thus, in the context of outpatient services, "day" signifies receipt of a service of a given type on that day.

These simplifications allowed us to create a single metric that may be summarized usefully despite the different data forms, varying levels of data quality, and procedure-specific variations in base units. These benefits may be restricted to system-level analyses like those presented here and consequently may be less useful for studies of treatment effectiveness or other instances in which greater detail on intensity are required. Also, in reporting on total and average treatment days across service categories—for example, the number of days of outpatient services received—it is important not to double-count service days.

Data quality checks were used to assess the accuracy and completeness of the data held by the Bureau of TennCare, and they revealed some limitations. For inpatient services, data for the period April 1995 to June 1996 were incomplete for one of the managed care organizations because of problems transferring the hospital records to the bureau's data system experienced by the firm's third-party billing administrator. The firm covers a sufficient number of enrollees that the remaining data would not be indicative of actual system performance; consequently, we do not report on inpatient services for SFY 1996.

Incompleteness for SFY 1995 did not grossly affect the number of youths served, although it did reduce the total number of inpatient days. There is some additional concern about inpatient data, because the state's psychiatric hospital system has had ongoing problems with its data submissions. Mathematica Policy Research, the TennCare demonstration's evaluators, also noted incompleteness in the inpatient data, but most of the problems they noted were concentrated in the medical data for adults (28).

Despite these limitations, we found the data to be sufficiently complete to present an initial picture of service patterns. A state audit has documented the accuracy of the data reported (29). If the data were incomplete, then that would be an important finding, allowing the state and the managed care firms to make any necessary corrections to the data for monitoring and evaluation purposes.

Sample description

The population of TennCare enrollees aged four to 17 years in the study years was predominantly white (61 percent), but substantially less so than the state's general population (80 percent) (30). These youths were predominantly pre- or primary-school-aged (64 percent, ages four to 11 years) and slightly more likely to be male (51 percent).

Analysis

Based on state-determined performance goals (31) and the literature on performance indicators (2,3,32,33), measures were calculated in four areas: overall access to behavioral health services, use of inpatient services, use of outpatient specialty treatment services, and use of supportive services such as case management and medication management. We used SAS (34) to process and analyze the data.

Overall access to behavioral health services was calculated as the annual number of youths who had any behavioral health service use per 1,000 TennCare enrollees. We also report the number of users and number of enrollees separately.

Use of inpatient services was addressed through several measures. We calculated the annual rate of use of any inpatient service per 1,000 TennCare enrollees and per 1,000 service users. We calculated length of stay for admissions on an annual basis. Lengths of stay are based on admission-level records and are indexed to the year of admission. For example, if a person was admitted on the last day of the year for seven days and had no other inpatient services in the next year, we recorded a seven-day length of stay in the year of admission and no inpatient admission in the next year. The average length of stay is the total of the lengths of stay for each admission in the year—including days that span into the next year—divided by the total number of admissions in the year.

We also calculated annual rates of readmission to inpatient care within 30 days. The number of readmissions within 30 days was based on the number of discharges in the year followed by an admission within 30 days. If a patient were discharged on the last day of a year, say 1996, but readmitted in 1997 within 30 days, the admission in the subsequent year (1997) counted as a readmission within 30 days in 1996. (It would also count as an admission in 1997.)

For use of outpatient specialty treatment services, we calculated the annual rate of specialty outpatient use across four key types of services—individual therapy, group therapy, family therapy, and partial hospitalization or day treatment—per 1,000 TennCare enrollees and separately for each service. We also calculated the average annual number of service days by service type and across the service types. To measure the use of case management services and medication management, we calculated annual rates of case management and medication management services per 1,000 TennCare enrollees and average annual number of days of these services.

Results

Overall access

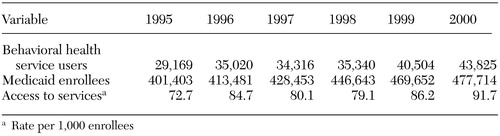

The overall findings on access to services are summarized in Table 1. The number of youths who received a behavioral service increased over time, from 29,169 in SFY 1995 to 43,825 in SFY 2000, an increase of nearly 50 percent. At the same time, the number of youths enrolled in TennCare increased, from 401,403 to 477,714, a 19 percent increase.

The annual access rate, as defined above, increased from 72.7 youths per 1,000 enrollees to 91.7. Thus, as the program expanded to cover more children, the system improved youths' access to behavioral health services overall.

Use of inpatient services

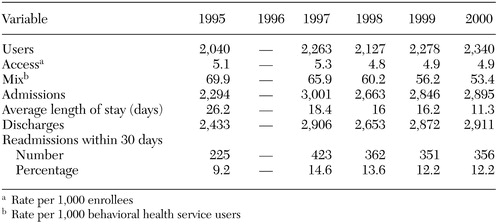

Table 2 presents the measures for inpatient care. The overall number of youths treated in inpatient facilities grew during the study period. As a proportion of all enrollees, the rate of use of inpatient services remained relatively stable at around five per 1,000. However, as a proportion of all youths who received a behavioral health service, the rate of inpatient use declined from 69.9 to 53.4 per 1,000 service users. This decline indicates a shift away from inpatient care as a method of treatment for youths in the TennCare program.

We cannot state definitively whether this shift represents a change in the severity mix caused by the influx of new enrollees or a change due to managed care, because the Medicaid claims and encounter data do not include data on severity or level of functioning. However, that the rate of inpatient service use in the population (inpatient service users per 1,000 enrollees) remained constant while the mix of inpatient care as a component of treatment (rate of inpatient service users per 1,000 service users) declined seems more consistent with patterns of inpatient service use in managed Medicaid systems (22) than a change in case mix. Some of the other expected patterns were also evident, such as substantially lower average lengths of stay (from 26.2 days per admission to 11.3) and increased rates of readmission within 30 days of discharge.

Outpatient specialty treatment services

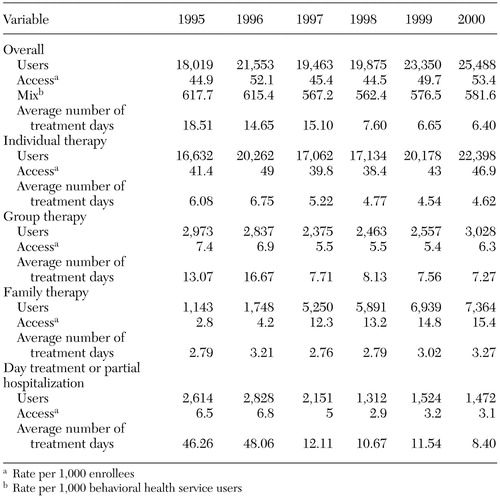

The rate of outpatient treatment services overall increased throughout the study period, but it was somewhat unstable (Table 3). In the two years before enactment of the behavioral health carve-out, TennCare Partners (SFYs 1995 to 1996), the rate of outpatient use grew from 44.9 to 52.1 per 1,000 enrollees. In the first year of the carve-out, the rate dropped back to 45.4 before increasing to pre-carve-out levels (53.4 per 1,000 enrollees in 2000).

Table 3 also displays the mix of specialty outpatient services used. As a proportion of behavioral service users, specialty outpatient treatment declined from about 618 users per 1,000 (62 percent) to 582 per 1,000 (58 percent) during the study period. By far the largest category of services was individual therapy. The pattern of interrupted growth at the time of TennCare Partners' implementation is more clearly evident here. Not only did the rate of access to individual therapy fall between SFYs 1996 and 1997, but the overall number of youths who received such services declined by 15 percent. However, the rates gradually returned to and exceeded the early TennCare performance levels. Group therapy followed a similar pattern. Use of day treatment or partial hospitalization declined sharply such that by the end of the observation period youths had used this service at less than half the rate of use before Partners. Family therapy, on the other hand, became more commonly used; its rate of use increased from 2.8 per 1,000 enrollees to 15.4 during the six-year period.

The most notable change, however, was in the volume of services per child. The average number of specialty outpatient treatment days per service user fell by two-thirds. This finding was driven in part by the declines in day treatment or partial hospitalization. However, the number of children using that type of service represented a small proportion overall. Of more impact was a one-third reduction in the number of individual therapy days per year. The rate of use of group therapy declined by nearly one-half.

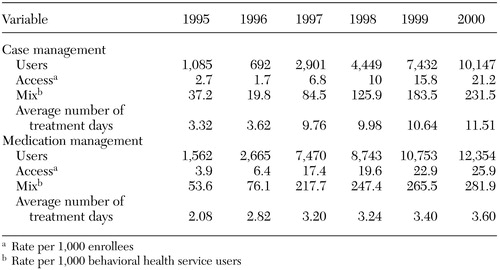

Case management and medication management

Table 4 shows the changes over time in the use of case management and medication management services. During the study period, the number of youths who were enrolled in case management increased tenfold. The rate of growth in use of this service more than offset the rate of growth in enrollment; access to case management increased from 2.7 per 1,000 enrollees to more than 21. The shift began with the implementation of Partners in SFY 1997, and the rate increases were associated with attention by the state, which created strong financial incentives for the behavioral health organization to provide case management to youths with severe emotional disturbances.

Thus provider incentives from the behavioral health organization were focused on the provision of case management as opposed to other types of treatment. Medication management rates likewise increased substantially. The access rate for medication management increased from 3.9 per 1,000 to more than 25.9 per 1,000. The increase may reflect greater identification of medication needs in the treatment of childhood mental disorders, or perhaps youths previously were receiving medications without appropriate medical supervision.

The relative importance of these services can be seen by their rate of use among users of behavioral health services. Less than 4 percent of youths in treatment in SFY 1995 received case management services, compared with 23 percent in SFY 2000. For medication management, the corresponding rates were about 5 percent and 28 percent.

In addition to the increased rates of use, TennCare was associated with an increase in the number of days on which children had contact with case managers and medication managers. The number of medication management days increased from 2.08 to 3.60, and the number of case management days increased from just over three days to 11.5 days per year, or an average of once a month. We are not sure why the number of case management users declined so sharply in SFY 1996. This finding may reflect an error in the completeness of the data.

Discussion

Despite tremendous growth in enrollment, the TennCare program has improved access to behavioral health services for school-aged children in terms of the number and rate of children receiving at least one behavioral health service. Our analysis shows that Medicaid managed behavioral health care in Tennessee has produced many of the anticipated effects in terms of the mix and intensity of services provided to children who are enrolled in Medicaid. However, the price of these expansions appears to have been reductions in the number of service days and a shift from treatment to support services.

For example, the rates of use of inpatient services among those who used services (the "mix" of inpatient care, using the rate per 1,000 service users) declined during the study period, and lengths of stay were less than half their initial level. Yet outpatient access rates remained at or above their initial levels, whereas the average number of days of outpatient treatment fell by nearly two-thirds. And although the rate of access to all services increased from roughly 7 percent to 9 percent of the youth population over the six-year observation period, a greater proportion of youths received greater amounts of treatment in the form of case management and medication management services. Thus the data do not support a conclusion that community treatment substituted for inpatient care in the treatment of children with emotional and behavioral problems.

These trends correspond with what is reported in much of the literature on Medicaid managed care for children and adolescents with emotional and behavioral problems reviewed by Hutchinson and Foster (21). Massachusetts experienced a slight increase in overall access and days of use for child Medicaid enrollees but demonstrated a significant decrease in access and days of use for children with disabilities (35). North Carolina (24) and Massachusetts (22) saw declines in inpatient stays and increases in readmission rates among children enrolled in Medicaid managed care. Although some studies have shown increases among subgroups of Medicaid-enrolled children in outpatient and pharmacy treatment that offset declines in inpatient care (36), in other studies the volume of outpatient services declined (23,25). Thus our study is consistent with previous studies in finding that declines in inpatient care do not necessarily lead to a corresponding increase in community-based treatment.

Some changes may warrant further attention by policy makers and researchers. First, additional information is needed about whether children experienced negative consequences of the declines in service volume. For example, if reductions in individual therapy visits do not result in worsening of children's conditions, then the cost savings represent a positive system change. However, if children experience worse outcomes, the state might consider alternative policies to protect them. An important addition to state data systems would be systematic outcome monitoring using nationally recognized, standardized measures of clinical outcomes, such as psychosocial functioning and symptoms.

Changes in day treatment or partial hospitalization may warrant special attention as well. Rates of use of these programs, which are an important part of systems of care for youths as an alternative to expensive hospital care, decreased by 52 percent, and the duration of the programs decreased by nearly two-thirds. However, these services are also more expensive than office-based community treatments. States may need to investigate whether providers systematically underreport day treatment or partial hospitalization services or whether such services are no longer being provided. A decline in this service may play a role in the observed increase in inpatient readmissions within 30 days, or it may reflect an adaptive response by the behavioral health organization, reflecting it perceptions about the relative contribution of this service to children's well-being in relation to its cost. To examine whether this pattern indicates a shift to more appropriate care, it will be necessary to incorporate outcome measures into the claims processing system or otherwise link population outcome data to population service use data. The decline in length of stay may be due to a common pattern of breaking inpatient stays into two or more smaller ones (22,37,38), given that rates of readmission within 30 days also increased during this period.

Another matter of concern is the discrepancy between access rates and rates of youths with behavioral health problems in this population. The rate of serious emotional disturbance in the TennCare population has been estimated at 26 percent (39). A mean rate of serious emotional disturbance of 15.9 percent has been estimated for community samples (40). These prevalence estimates are substantially higher than the access estimates we found, which is consistent with other national surveys (41). Compared with estimates from the Children's Mental Health Benchmarking Project (CMHBP), Tennessee would seem to be somewhere in the middle. However, the rates reported by the CMHBP are for children and adolescents between birth and 17 years of age. In Tennessee, when youths under the age of four years were included, the access rates dropped by about one-quarter (not reported here), because the younger age group tends not to use many behavioral health services: they contribute a large number of enrollees (the denominator of the access rate) but relatively few users (the numerator).

The results of this study are limited by the quality and completeness of the TennCare data. As noted above, some data may be missing from state information systems. Even when the data are reported, more substantial monitoring of data quality may be necessary. For example, although this article reports on inpatient care, the distinction between inpatient and other types of care—for example, residential care—may reflect billing artifacts. A behavioral health organization might nominally step down a youth from inpatient to residential to intensive outpatient care, when, in fact, the youth remains in the same residential setting but at a lower reimbursement rate (42).

An important first step in this regard will be to increase the incentives to report complete and accurate data and more finely grained evaluation of submitted claims or encounters. This approach will mean checking more than just the presence or validity of diagnosis codes and other fields on a given claim. In addition, the issues of "appropriateness" and effectiveness of care are not addressed by performance indicators such as these and require other forms of monitoring, such as focus groups and cohort studies, as used in some of the earlier monitoring of TennCare (43).

Conclusions

The TennCare program made great strides during the period 1994 to 2000 in attempting to maximize health coverage for vulnerable populations, especially children. The implementation of TennCare accelerated the pace of previous eligibility phase-ins in Tennessee, extended coverage to a sizable number of youths who would otherwise not have qualified for private or public insurance, and in many ways presaged the federal Children's Health Insurance Plan.

However, TennCare may be a victim of its own success. Although the number of children served increased during the study period, TennCare greatly reduced the volume of care that children received for their identified emotional and behavioral problems. We do not know what the consequences of these reductions are for the affected children. Furthermore, the extraordinary increase in the number of people served has made the program more costly than anticipated. Thus, until July 2002, Tennessee was among the states with the lowest level of uninsured children (44), but recent changes in the TennCare waiver program have resulted in the disenrollment of a large number of children. Current reform efforts have separated the uninsured or uninsurable population from the Medicaid population and offer a separate limited insurance benefit with a more stringent income requirement. The impact of this change will need close monitoring.

These data are the first system performance measures from the TennCare data systems generated for public discussion and have been provided through an independent university research team. However, both the state and the private behavioral health contractor are taking positive steps to produce and share similar indicators. The private behavioral health contractor reports on service use at several public forums, and the Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities and the Bureau of TennCare are collaborating to develop the resources and databases to monitor behavioral health services under the TennCare Partners Program, including developing a performance indicator monitoring plan (45).

Effective monitoring and oversight of managed care contractors, state agencies, and behavioral health providers requires a strong public data system. This requirement includes having the resources, expertise, and authority to produce information about types and amounts of services, the number of children and adolescents served, and outcomes of service. These measures and efforts by the state and the managed care companies are important first steps on the road to concurrent evaluation of the behavioral health service delivery system for youths in Tennessee.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants UR7-TI11332 and KD1-TI12328 from the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, grant R01-DA12982 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and grant R21-AA12432 from the National Institute for Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse.

The authors are affiliated with the department of human organization and development of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. Send correspondence to Mr. Saunders at Box 90 GPC, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee 37203 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Service use and enrollment data for Medicaid-enrolled children and adolescents aged four to 17 years, state fiscal years 1995 to 2000

|

Table 2. Inpatient service use data for children and adolescents aged four to 17 years, state fiscal years 1995 to 2000

|

Table 3. Number of outpatient specialty service users, access rates, and average number of treatment days among children and adolescents aged four to 17 years, state fiscal years 1995 to 2000

|

Table 4. Number of support services users, access rates, and average number of treatment days for children and adolescents aged four to 17 years, state fiscal years 1995 to 2000

1. Book I: HEDIS 3.0: Understanding and Enhancing Performance Measurement. Washington, DC, National Committee for Quality Assurance, 1997Google Scholar

2. Mental Health Statistics Improvement Program: Consumer-Oriented Mental Health Report Card. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1996Google Scholar

3. Perlman SB, Nechasek SL, Dougherty RH: Children's mental health benchmarking: progress and potential. Behavioral Healthcare Tomorrow 10(3):14,36–37, 1999Google Scholar

4. Children's Mental Health Benchmarking Project: Second-Year Report. Lexington, Mass, Dougherty Management Associates, Inc, 2002. Available at www.doughertymanagement.comGoogle Scholar

5. Lambrew J: Section 1115 waivers in Medicaid and the State Children's Health Insurance Program, an overview. Washington, DC, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2001. Available at www.kff.org/content/2001/4001/4001.pdfGoogle Scholar

6. Chang CF, Kiser LJ, Bailey JE, et al: Tennessee's failed managed care program for mental health and substance abuse services. JAMA 279:864–869, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Young C, Meyer T, Wrenn K, et al: Access to emergency care under TennCare: do patients understand the system? Annals of Emergency Medicine 30:281–285, 1997Google Scholar

8. Hulen KD, Beeler LM: TennCare: the impact of state health care reform on emergency patients and caregivers. Journal of Emergency Nursing 21:282–286, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Wrenn K, Slovis C: TennCare in the emergency department: the first 18 months. Annals of Emergency Medicine 27:231–233, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Ray WA, Gigante J, Mitchell EF, et al: Perinatal outcomes following implementation of TennCare. JAMA 279:314–316, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Cooper WO, Hickson GB, Mitchel EF, et al: Comparison of perinatal outcomes among TennCare Managed Care Organizations. Pediatrics 104:525–529, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Sloan FA, Conover CJ, Mah ML, et al: Impact of Medicaid managed care on utilization of obstetric care: evidence from TennCare's early years. Southern Medical Journal 95:811–821, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Sloan FA, Rankin PJ, Whellan DJ, et al: Medicaid, managed care, and the care of patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction. American Heart Journal 139:567–576, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Holzman MD, Mitchel EF, Ray WA, et al: Use of healthcare resources among medically and surgically treated patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a population-based study. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 192:17–24, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Cooper WO, Staffa JA, Renfrew JW, et al: Oral corticosteroid use among children in TennCare. Ambulatory Pediatrics 2:375–381, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Hill SC, Wooldridge J: Plan characteristics and SSI enrollees' access to and quality of care in four TennCare MCOs. Health Services Research 37:1197–1220, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Lyons W, Scheb JM: Managed care and Medicaid reform in Tennessee: the impact of TennCare on access and health-seeking behavior. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 10:328–337, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Rocha CJ, Kabalka LE: A comparison study of access to health care under a Medicaid managed care program. Health and Social Work 24:169–179, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Heflinger CA, Simpkins CG, Scholle SH, et al: Parent/caregiver satisfaction with their child's Medicaid plan and behavioral health providers. Mental Health Services Research (in press)Google Scholar

20. Moreno L, Hoag SD: Covering the uninsured through TennCare: does it make a difference? Health Affairs 20(1):231–239, 2001Google Scholar

21. Hutchinson AB, Foster EM: The effect of Medicaid managed care on mental health care for children: a review of the literature. Mental Health Services Research 5:39–54, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Dickey B, Normand SL, Norton EC, et al: Managed care and children's behavioral health services: the Massachusetts experience. Psychiatric Services 52:183–188, 2001Link, Google Scholar

23. Callahan JJ, Shepard DS, Beinecke RH, et al: Mental health/substance abuse treatment in managed care: the Massachusetts Medicaid experience. Health Affairs 14(3):173–184, 1995Google Scholar

24. Burns BJ, Teagle SE, Schwartz M, et al: Managed behavioral health care: a Medicaid carve-out for youth. Health Affairs 18(5):214–225, 1999Google Scholar

25. Catalano R, Libby A, Snowden L, et al: The effect of capitated financing on mental health services for children and youth: the Colorado experience. American Journal of Public Health 90:1861–1865, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Medicaid Managed Care: Four States' Experiences With Mental Health Carveout Programs. Pub no GAO/HEHS-99–118. Washington, DC, US General Accounting Office, 1999Google Scholar

27. IMPACT Study of TennCare and Mississippi Medicaid. Center for Mental Health Policy, Vanderbilt Institute for Public Policy Studies. Available at www.vanderbilt.edu/VIPPS/CMHP/publications.html#impactGoogle Scholar

28. Sing M: Problems With Using Encounter Data From Medicaid HMOs for Research and Monitoring. Princeton, NJ, Mathematica Policy Research, 2001Google Scholar

29. Division of State Audit: Performance Audit: Medicaid Encounter Data, December 2001. Nashville, Tenn, Comptroller of the Treasury, 2002Google Scholar

30. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics for Tennessee, 2000. Press release, US Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 2003. Available at www.census.gov/press-release/www/2001/tables/dp_tn_2000.xlsGoogle Scholar

31. TennCare Partners Performance Indicators. Nashville, Tenn, Tennessee Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation, 1996Google Scholar

32. A Proposed Consensus Set of Indicators for Behavioral Health. Pittsburgh, American College of Mental Health Administrators, 2001Google Scholar

33. Book III: HEDIS 3.0: Measurement Specifications. Washington, DC, National Committee for Quality Assurance, 1997Google Scholar

34. SAS for Windows, version 8.2. Cary, NC, SAS InstituteGoogle Scholar

35. Beinecke RH, Shepard DS, Goodman M, et al: Assessment of the Massachusetts Medicaid managed behavioral health program: year three. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 24:205–220, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Norton EC, Lindrooth RC, Dickey B: Cost-shifting in a mental health carve-out for the AFDC population. Health Care Financing Review 18:185–196, 1997Google Scholar

37. Foster EM: Do aftercare services reduce inpatient psychiatric readmissions? Health Services Research 34:715–736, 1999Google Scholar

38. Foster EM: Does the continuum of care reduce inpatient length of stay? Evaluation and Program Planning 23:53–65, 2000Google Scholar

39. Heflinger CA, Simpkins CG, Northrup DA, et al: The Status of TennCare Children and Adolescents: Behavioral Health, Health, Service Use, and Customer Satisfaction: The IMPACT Study Baseline Report on Interview Data. Nashville, Tenn, Center for Mental Health Policy, Vanderbilt Institute for Public Policy Studies, 2000Google Scholar

40. Roberts RW, Attkisson CC, Rosenblatt A: Prevalence of psychopathology among children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:715–725, 1998Link, Google Scholar

41. Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB: Unmet need for mental health care among US children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1548–1555, 2002Link, Google Scholar

42. Northrup D, Heflinger CA: Substance Abuse Treatment Services for Publicly Funded Adolescents in the State of Tennessee. Nashville, Tenn, Vanderbilt Center for Mental Health Policy, 2000. Available at www.vanderbilt.edu/vipps/cmhp/pdfs/tnpublicaod.pdfGoogle Scholar

43. Lehman AF, Osher FC: Report to Health Care Financing Administration: Assessment of the Current Operation of the TennCare Partners Program With Respect to the State's Corrective Action Plan. Baltimore, Health Care Financing Administration, 1998Google Scholar

44. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured: Health Coverage for Low-Income Children. Washington, DC, Kaiser Family Foundation, 2002Google Scholar

45. Progress Report on the TennCare Partners Program. Nashville, Tenn, Bureau of TennCare and Department of Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities, 2002Google Scholar