Appropriateness of Prescribing Practices for Serotonergic Antidepressants

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Data from prescribing physicians were used to assess whether serotonergic antidepressants were used for appropriate indications and at appropriate initial dosages. METHODS: Data were derived from the confidential logs of psychiatrists and primary care physicians who provided prescription information from January 1, 1997, through June 30, 1999, as part of the National Disease and Therapeutic Index physician survey. The survey is not affiliated with a reimbursement system and therefore minimizes bias related to reimbursement. Data on the primary reason for use and the dosage at the time of first use were obtained for prescriptions of citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine, and extended-release venlafaxine. RESULTS: Depressive disorders accounted for the majority of the 3,206 prescriptions for the six antidepressants (74 percent to 86.2 percent). The next most common indications for use were anxiety (4.1 percent to 12.6 percent) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (1.3 percent to 3.3 percent). For patients with depressive disorders, psychiatrists prescribed slightly higher antidepressant dosages than primary care physicians. CONCLUSIONS: Serotonergic antidepressants are used primarily for the treatment of depression and depression-related disorders and are prescribed at the recommended starting dosages.

The introduction of fluoxetine and other serotonergic antidepressants over the past decade and a half has changed the treatment of depressive and other mood disorders. Although just as efficacious as the tricyclic antidepressants, the serotonergic antidepressants are associated with a more tolerable pharmacologic profile, making them easy to use for both the provider and the patient (1). This user-friendly profile has been associated with a rapid rise in the number of people who receive antidepressants (2). However, despite a substantial increase in the number of people treated for depression, epidemiological surveys have suggested that the rate of untreated depression has not declined (3,4,5), perhaps suggesting that the new users of antidepressants may not be those with the greatest need (6).

The rapid growth in the number of users has raised concern that the newer antidepressants may be used for minor mood disorders or lifestyle adjustments that previously would not have been considered serious enough to require medication or other treatment (7). In addition to major depression, other appropriate indications for serotonergic antidepressants could account for some of the increased use. Various antidepressants have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and bulimia. However, to our knowledge, the extent of serotonergic antidepressant use for these disorders has not been investigated.

The most common methods used to assess drug utilization and the appropriateness of antidepressant treatment are analysis of insurance claims and medical chart review. Although these methods are useful, they have many limitations, especially in the study of treatment for mental illness (8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17). Studies have suggested that physicians frequently and intentionally misrepresent disorders in insurance claims and charts to gain approval for medical care, to avoid problems with reimbursement, or to improve a patient's future insurability (18,19). Various carve-out and alternative financing arrangements further complicate assessments of drug utilization based on claims data. Because of these limitations, interpretation of any particular utilization analysis must take into account its heavy dependence on the data source and the method of gathering data (20).

The objective of this study was to assess two aspects of appropriate prescription of antidepressants—indication for use and initial dosage—by primary care physicians and by psychiatrists. The study used data from the National Disease and Therapeutic Index physician survey (21), a source that is unencumbered by the usual limitations. The survey uses confidential logbooks in which physicians record information for each prescribing event over a specific period (22). Because it is not connected with a reimbursement system, the National Disease and Therapeutic Index minimizes bias related to reimbursement and could provide a better representation of the disorders for which serotonergic antidepressants are being prescribed. The study reported here examined the use of six commonly used and representative serotonergeric antidepressants: citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, venlafaxine, and extended-release venlafaxine. We chose these drugs because they are the most frequently prescribed serotonergic antidepressants and thus are those most often subject to criticism about inappropriate use.

Methods

Data source

Data for patients who received their first antidepressant prescription from either a primary care physician or a psychiatrist between January 1, 1997, and June 30, 1999, were obtained from the National Disease and Therapeutic Index physician survey (21). Data for the survey are obtained from confidential logbooks completed each quarter by 2,490 office-based physicians in the United States. This sample includes 180 psychiatrists and 813 primary care physicians, and we report the responses of these 993 practitioners.

Physicians are recruited to participate in the National Disease and Therapeutic Index survey from a sampling frame based on the American Medical Association and American Osteopathic Association listings of all practicing physicians. The participating physicians record the indication and dosage at the time of each prescribing event for every prescription written on two consecutive, randomly assigned days per quarter. We used each prescription written during a discrete patient visit as the unit of analysis. Because the logbooks do not identify specific patients, patient confidentiality was protected.

The data included the physician's specialty, the indication for the prescription, and additional information about the prescription, such as the medication name, the strength, and the dosage. The primary care physicians in the sample included physicians in family practice, general practice, internal medicine, and osteopathic medicine. The indication for use was assigned on the basis of ICD-9-CM categories. The categories considered for this study were based on ICD-9-CM codes specified to the fourth digit and were chosen a priori under the assumption that they would be the most prominent categories associated with antidepressant medication in the National Disease and Therapeutic Index. They included depressive disorders, anxiety states, obsessive-compulsive disorders, eating disorders, stress, phobia, obesity, schizophrenia and psychotic disorders, and "all others."

The category of all others included all the remaining medical and psychological disorders that appeared in the logs. These disorders were further divided into the three subclassifications developed by Rost and associates (20): depression-related disorders, other mental health indications, and other medical conditions. The depression-related disorders consisted of indications that share the symptoms of major depression. Rost and associates found that physicians treating depressed patients may make a diagnosis of one of these related disorders instead of depression. A complete list of the diagnostic indications included in this study is available from the authors.

Information on both indication and dosage at the time of the first use of an antidepressant was included in our analyses. We used data on the prescribed strength and dosing regimen to analyze the antidepressant dosage. The daily dosage was calculated by multiplying the product strength by the number of doses per day in the dosing regimen. For example, a 20 mg tablet at a dosage of two tablets a day, once daily, was recorded as a 40 mg daily dosage for the purposes of this analysis. Only 41 prescriptions (1.3 percent) had incomplete data, such as a lack of information on the strength or dosing regimen. Data for these prescriptions were excluded from our analyses, which left 3,206 unique antidepressant prescription events for analysis.

Editor's Note: This paper is part of a series on the treatment of depression edited by Charles L. Bowden, M.D. Contributions are invited that address major depression, bipolar depression, dysthymia, and dysphoric mania. Papers should focus on integrating new information for the purpose of improving some aspect of diagnosis or treatment. For more information, please contact Dr. Bowden at the Department of Psychiatry, Mail Code 7792, University of Texas Health Science Center, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, Texas 78229-3900; 210-567-6941; [email protected].

Statistical analysis

Differences in antidepressant use for each indication and differences in use by the specialty of the prescribing physician were tested with contingency-table chi square tests of independence. For the subsample of patients with depressive disorders, we used two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test for differences in mean starting dosages. The two factors were physician specialty (psychiatrist or primary care physician) and antidepressant choice (the six medications). Because dosage data for individual patients were not available, the ANOVA compared mean dosages weighted by the number of patients—that is, with the weight inversely proportional to the variance. Because all interactions between the two factors were very small numerically, we used the interaction mean square (df=5) as our error term (denominator) in significance testing.

Finally, because the six antidepressants we studied have a wide range of recommended starting dosages—20 to 75 mg a day—the ANOVA used mean dosages expressed as equivalent dosages of fluoxetine. For example, the recommended starting dosage is 75 mg a day for extended-release venlafaxine and 20 mg a day for fluoxetine. Thus we multiplied the observed mean dosage of extended-release venlafaxine by .2666 (20 divided by 75) to convert it to fluoxetine-dosage-equivalent units. Recommended starting dosages are 20 mg a day for citalopram, fluoxetine, and paroxetine; 50 mg a day for sertraline; and 75 mg a day for venlafaxine and extended-release venlafaxine. We used JMP version 3.2 for Windows for all ANOVA computations.

Results

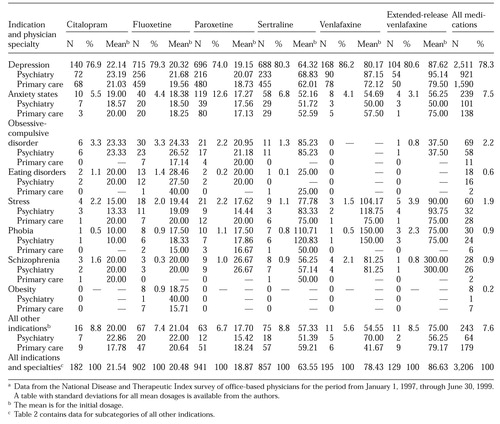

Table 1 lists the number of prescriptions for serotonergic antidepressants, along with mean dosage, by indication and by the specialty of the prescribing physician. Although conversion to fluoxetine equivalents was necessary to yield valid ANOVA results in comparing the mean dosages of medications with different recommended starting dosages, the mean dosages reported in the table are not expressed in fluoxetine-equivalent units. Although some readers might have found fluoxetine-equivalent scaling useful for making comparisons between the columns of the table, others might have found this standardization confusing or potentially misleading.

Of the total of 3,206 antidepressant prescriptions included in the analysis, 5.7 percent (N=182) were for citalopram, 28.1 percent (N=902) for fluoxetine, 29.4 percent (N=941) for paroxetine, 26.7 percent (N=857) for sertraline, 6.1 percent (N=195) for venlafaxine, and 4 percent (N=129) for extended-release venlafaxine. Approximately 61 percent of the prescriptions (N=1,963) were written by primary care physicians. Of these, 4.2 percent (N=82) were for citalopram, 28 percent (N=550) for fluoxetine, 32.1 percent (N=630) for paroxetine, 28 percent (N=550) for sertraline, 4.6 percent (N=90) for venlafaxine, and 3.1 percent (N=61) for extended-release venlafaxine.

Among the 1,243 prescriptions written by psychiatrists, 8.1 percent (N=100) were for citalopram, 28.2 percent (N=352) for fluoxetine, 25.1 percent (N=311) for paroxetine, 24.6 percent (N=307) for sertraline, 8.5 percent (N=105) for venlafaxine, and 5.4 percent (N=68) for extended-release venlafaxine.

Indications for use

As Table 1 shows, depressive disorders accounted for more than three-quarters of the evaluated indications. The proportion of prescriptions for a depressive disorder varied significantly across the antidepressants (χ2= 20.59, df=5, p<.001). When we stratified the patient sample by physician specialty and antidepressant medication, we found that 69.5 percent to 85.7 percent of the prescriptions written by psychiatrists and 76.2 percent to 86.7 percent of the prescriptions written by primary care physicians were for depressive disorders. For each physician specialty, the proportion of use for diagnoses of depressive disorders varied significantly across the antidepressants (psychiatrists, χ2=12.97, df=5, p=.02; primary care physicians, χ2=14.80, df=5, p=.01). Overall, however, psychiatrists were more likely than primary care physicians to prescribe antidepressants for diagnoses other than depression.

Anxiety states were the second most common reason for prescribing antidepressants. Although 12.6 percent of the paroxetine prescriptions were for the treatment of anxiety states, the proportion of use of the other antidepressants for anxiety states ranged from 3.1 percent to 6.8 percent, a significant difference (χ2=57.01, df=5, p<.001). The differences in use for anxiety states across the antidepressants were found for both psychiatrists (χ2=11.78, df=5, p=.04) and primary care physicians (χ2=47.70, df=5, p<.001).

Use of antidepressants for the remaining categories—obsessive-compulsive disorder, eating disorders, stress, phobia, schizophrenia, and obesity—was relatively uncommon. The combined categories accounted for only 6.6 percent of all prescriptions, or 213 of the 3,206 prescriptions.

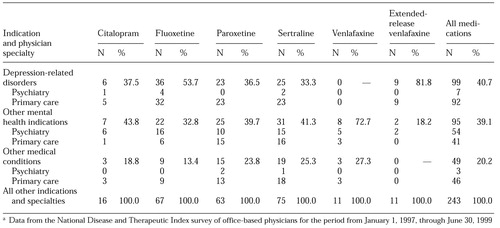

Use of antidepressants for conditions represented in the "all others" category accounted for 7.6 percent of all prescriptions. However, because this category included indications that may not be considered appropriate, we thought it merited further investigation. Data from this category, which may include indications not related to mental disorders, are presented in Table 2. Most of the prescriptions in the category were written for depression-related disorders and mental health disorders. The "other medical conditions" subclassification included only 49 (20.2 percent) of the 243 prescriptions in the all others category, or about 1.5 percent of the entire sample. Prescriptions by primary care physicians represented nearly 94 percent of the prescriptions for other medical conditions.

Starting dosage

The overall mean daily dosage at the time of the initial prescription, as listed at the bottom of Table 1, was 21.5 mg for citalopram, 20.5 mg for fluoxetine, 18.9 mg for paroxetine, 63.6 mg for sertraline, 78.4 mg for venlafaxine, and 86.6 mg for extended-release venlafaxine. For each antidepressant, the mean initial dosage for depressive disorders was very similar to the overall mean initial dosage for all indications. The other indications were associated with highly variable dosing. For example, for all agents, the mean starting dosage for anxiety states tended to be lower than the overall mean dosage for each drug, ranging from 1.6 mg (1.6 fluoxetine-equivalent units) a day less for paroxetine to 30.4 mg (8.1 fluoxetine-equivalent units) a day less for extended-release venlafaxine.

On the other hand, the mean initial dosages used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder tended to be higher than the overall mean for each medication, ranging from 1.8 mg (1.8 fluoxetine-equivalent units) a day higher for citalopram to 21.7 mg (8.7 fluoxetine-equivalent units) a day higher for sertraline. However, for each antidepressant, fewer than 25 prescriptions each were written for eating disorders, stress, phobia, schizophrenia, and obesity, and these differences were not statistically significant.

With some exceptions, psychiatrists tended to initiate treatment at slightly higher dosages than primary care physicians. Compared with psychiatrists, primary care physicians tended to use higher dosages of sertraline, citalopram, venlafaxine, and extended-release venlafaxine for anxiety states; higher dosages of fluoxetine, paroxetine, and citalopram for stress; and higher dosages of paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine for indications in the all others category.

A total of 2,511 prescriptions were for patients with a diagnosis of depressive disorder. A two-way ANOVA indicated that the mean starting dosages for these prescriptions, containing only main effects for physician specialty (two levels) and the six antidepressant choices, revealed significant differences in mean starting dosages (F=44.25, df=6, 5, p<.001). In particular, for treatment of depressive disorders, psychiatrists prescribed slightly higher dosages than primary care physicians (F=39.69, df=1, 5, p<.002). The starting dosage of sertraline for depressive disorders was higher than the starting dosage of fluoxetine (F=115.35, df=1, 5, p<.001). On the other hand, paroxetine was associated with a lower mean starting dosage, compared with fluoxetine (F=50.41, df=1, 5, p<.001). The mean starting dosages of citalopram, venlafaxine, and extended-release venlafaxine were not statistically different from the mean starting dosage of fluoxetine.

All the mean starting dosages reported in Table 1—both those prescribed by psychiatrists and those prescribed by primary care physicians—were close to the recommended starting dosage for each antidepressant. In other words, although some differences in mean dosages were statistically significant, we believe that these differences were too small to be clinically meaningful.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that the majority of the serotonergic antidepressant prescriptions included in our sample were for treatment of depressive disorders (78.3 percent) and that very few (1.5 percent) were written for non-mental health reasons. Statistically significant differences in mean starting dosages between antidepressants and between physician specialties were found for prescriptions for treatment of a depressive disorder, but these differences were not large and are probably not clinically relevant.

Our findings are similar to those of other studies that have found appropriate use of antidepressants. A British study found that a diagnosis of a depressive disorder was recorded in general practice physicians' medical notes for 75 percent of 189 antidepressant users (23). A French study that used structured clinical interviews to confirm the diagnosis of fluoxetine users obtained similar results (24). In a German study that looked at both psychiatric and general practice patients, about 90 percent of fluoxetine recipients had a diagnosis of depression (25).

The observed tendency of the psychiatrists in this study to prescribe antidepressants for reasons other than depression and to prescribe higher dosages than primary care physicians is also consistent with the findings of other studies. Because psychiatrists are more likely than primary care physicians to see patients with more severe and complex mental illnesses (22,25,26,27), this finding may reflect differences in patient mix and illness severity (3,26).

An analysis based on National Disease and Therapeutic Index survey data, which were used in this study, has many advantages over reviews that use medical insurance claims. Physicians participating in the survey record the patient's diagnosis concurrently for each prescribing event, which minimizes the recall bias that might occur when physicians chart and complete encounter forms at the end of a busy day. Because the physicians who contribute data to the National Disease and Therapeutic Index were compensated for their participation, these data may be more complete and thorough than those found in administrative databases. Also, because the confidential logbooks were not linked to any administrative or reimbursement systems, the data are not biased by the potential for reduced reimbursement, loss of insurability, or social stigma. These advantages, as well as the ability to produce tightly linked information about diagnosis, medication choice, and physician specialty from the survey data, may enable more accurate assessment of the use of medications and the appropriateness of antidepressant treatment than analyses based on data from other sources. Studies of medication use that fail to account for differences in diagnosis across medications are likely to result in flawed inferences about those medications (28).

Despite its many strengths, our study nevertheless failed to address many important aspects of appropriate use of antidepressants. Although we feel confident that the National Disease and Therapeutic Index data show that antidepressants were not overprescribed and that starting dosages for treatment of depression were not inappropriately high, we could not assess the appropriateness of certain low mean starting dosages. Low initial dosages could have been related to the need to minimize the potential for side effects or drug interactions for certain patients or to other appropriate decisions made by physicians. The National Disease and Therapeutic Index data do not help confirm or contradict the earlier finding that depressed patients tend to receive an inappropriately short duration of serotonergic antidepressant treatment (29,30). Similarly, the data shed no light on the question of whether these medications are inappropriately underprescribed and whether titration is appropriate.

Our study had other potential limitations. The National Disease and Therapeutic Index sample includes only office-based physicians, so patients who rely primarily on medical clinics or hospital settings for their medical care are not represented in the data (22). Because the unit of analysis is the prescribing event and not the patient treatment episode, the National Disease and Therapeutic Index survey may overestimate the number of prescriptions and underestimate the dosages, because individual patients potentially could visit more than one physician participating in the survey and receive multiple antidepressant prescriptions (21).

As is typical of information in many claims and medical databases, the diagnoses reported in the National Disease and Therapeutic Index depend on the impressions of the treating physicians rather than on objective clinical measures and standardized tests. The accuracy of the diagnosis thus depends on the participating physicians' training and experience in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders. This training and experience may vary widely, but we do not have data to address this point. The relevance and generalizability of these data are limited by the accuracy of the recorded diagnoses (31).

Many other questions remain to be addressed in future research. Expansion of managed care has been associated with increasing use of drug utilization review, cost sharing, and other mechanisms that may influence prescribing behavior. Although many persons with depressive disorders are untreated or inadequately treated, such undertreatment clearly can coexist with the overuse of antidepressants (6). Furthermore, we know little about the relationship between the severity of various illnesses and antidepressant use. Only prospective cohort designs that use structured interviews can definitively address these questions.

Conclusions

This study found that, according to physicians' self-report, treatment with serotonergic antidepressants was initiated for appropriate medical reasons and, for patients with a depressive disorder, at recommended dosages. However, further research is necessary to improve our understanding of the nature of antidepressant use.

Acknowledgment

This work was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

The authors are affiliated with the outcomes research group at Eli Lilly and Company. Dr. Obenchain and Dr. Croghan are also affiliated with the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis. Send correspondence to Dr. Croghan, Outcomes Research Group, Eli Lilly and Company, Drop Code 1850, Lilly Corporate Center, Indianapolis, Indiana 46285 (e-mail, [email protected]). Parts of this paper were presented as a poster at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association held May 15-20, 1999, in Washington, D.C.

|

Table 1. Number of prescription for serotonergic antidepressants and mean initial dosage, by indication and speciality of the prescribing physiciana

a Data from the National Disease and Therapeutic Index survey of office-based physicians for the period from January 1, 1997, through June 30, 1999A table with standard deviations for all mean dosages is available from the authors.

|

Table 2. Number of prescription for serotonergic antidepressants for indications included in the "all other" category, by speciality of the prescribing physiciana

a Data from the National Disease and Therapeutic Index survey of office-based physicians for the period from January 1, 1997, through June 30, 1999

1. Rudorfer MV, Potter WZ: Antidepressants: a comparative review of the clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use of the "newer" versus the "older" drugs. Drugs 37:713-738, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Johnson RE, McFarland BH, Nichols GA: Changing patterns of antidepressant use and costs in a health maintenance organisation. Pharmacoeconomics 11:274-286, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Katzelnick DJ, Kobak KA, Jefferson JW, et al: Prescribing patterns of antidepressant medications for depression in a HMO. Hospital Formulary 31:374-376, 1996Google Scholar

4. Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al: A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:924-932, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:55-61, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Croghan TW: The controversy of increased spending for antidepressants. Health Affairs 20(2):129-135, 2001Google Scholar

7. Streater SE, Moss JT: Non-approved usage identification of off-label antidepressant use and costs in a network model HMO. Drug Benefit Trends 9:42,48-50,55-56, 1997Google Scholar

8. Lloyd SS, Rissing JP: Physician and coding errors in patient records. JAMA 254:1330-1336, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Bright RA, Avorn J, Everitt DE: Medicaid data as a resource for epidemiologic studies: strengths and limitations. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 42:937-945, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hsia DC, Krushat WM, Fagan AB, et al: Accuracy of diagnostic coding for Medicare patients under the prospective-payment system. New England Journal of Medicine 318:352-355, 1988; erratum, New England Journal of Medicine 322:1540, 1990Google Scholar

11. Motheral BR, Fairman KA: The use of claims databases for outcomes research: rationale, challenges, and strategies. Clinical Therapeutics 19:346-366, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Strom BL, Carson JL: Use of automated databases for pharmacoepidemiology research. Epidemiologic Reviews 12:87-107, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Garnick DW, Hendricks AM, Comstock CB: Measuring quality of care: fundamental information from administrative datasets. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 6:163-177, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Lohr KN: Use of insurance claims data in measuring quality of care. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 6:263-271, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Iezzoni LI, Foley SM, Daley J, et al: Comorbidities, complications, and coding bias: does the number of diagnosis codes matter in predicting in-hospital mortality? JAMA 267:2197-2203, 1992Google Scholar

16. Tierney WM, McDonald CJ: Practice databases and their uses in clinical research. Statistics in Medicine 10:541-557, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Poses RM, Smith WR, McClish DK, et al: Controlling for confounding by indication for treatment: are administrative data equivalent to clinical data? Medical Care 33(suppl 4):AS36-AS46, 1995Google Scholar

18. Freeman VG, Rathore SS, Weinfurt KP, et al: Lying for patients: physician deception of third-party payers. Archives of Internal Medicine 159:2263-2270, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Rost K, Smith R, Matthews DB, et al: The deliberate misdiagnosis of major depression in primary care. Archives of Family Medicine 3:333-337, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Browne RA, Melfi CA, Croghan TW, et al: Issues to consider when conducting research using physician-reported antidepressant claims. Drug Benefit Trends 10:33,37-42, 1998Google Scholar

21. National Disease and Therapeutic Index Manual. Plymouth Meeting, Penn, IMS Health, 1996Google Scholar

22. Olfson M, Klerman GL: The treatment of depression: prescribing practices of primary care physicians and psychiatrists. Journal of Family Practice 35:627-635, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

23. Donoghue JM, Tylee A: The treatment of depression: prescribing patterns of antidepressants in primary care in the UK. British Journal of Psychiatry 168:164-168, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Bouhassira M, Allicar MP, Blachier C, et al: Which patients receive antidepressants? A "real world" telephone study. Journal of Affective Disorders 49:19-26, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Dittmann RW, Linden M, Osterheider M, et al: Antidepressant drug use: differences between psychiatrists and general practitioners: results from a drug utilization observation study with fluoxetine. Pharmacopsychiatry 30(suppl 1):28-34, 1997Google Scholar

26. Shasha M, Lyons JS, O'Mahoney MT, et al: Serotonin reuptake inhibitors and the adequacy of antidepressant treatment. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 27:83-92, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Bingefors K, Isacson D, von Knorring L: Antidepressant dose patterns in Swedish clinical practice. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 12:283-290, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Gibson P, Edgell E, Loosbrock D, et al: Apples and apples, apples and oranges: the use and abuse of average daily dose in pharmacoeconomic research. Value in Health 2:227-228, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R: Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatric Services 49:196-201, 1998Link, Google Scholar

30. Streja DA, Hui RL, Streja E, et al: Selective contracting and patient outcomes: a case study of formulary restrictions for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants. American Journal of Managed Care 5:1133-1142, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

31. Olfson M, Klerman GL: Trends in the prescription of psychotropic medications: the role of physician specialty. Medical Care 31:559-564, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar