Characteristics of Psychiatric Patients for Whom Financial Considerations Affect Optimal Treatment Provision

Abstract

This study assessed characteristics of psychiatric patients for whom financial considerations affected the provision of "optimal" treatment. Psychiatrists reported that for 33.8 percent of 1,228 patients from a national sample, financial considerations such as managed care limitations, the patient's personal finances, and limitations inherent in the public care system adversely affected the provision of optimal treatment. Patients were more likely to have their treatment adversely affected by financial considerations if they were more severely ill, had more than one behavioral health disorder or a psychosocial problem, or were receiving treatment under managed care arrangements. Patients for whom financial considerations affect the provision of optimal treatment represent a population for whom access to treatment may be particularly important.

Two trends raise concerns about access to psychiatric treatment: significant reductions in mental health and substance abuse benefits coverage (1,2) and dramatic changes in the management of benefits as a result of incentives to contain costs and utilization in managed care delivery systems (3,4).

Although numerous state and federal parity bills have been enacted since 1998, no major changes have been observed in disparities between mental health benefits and general medical benefits (5). In fact, one report indicates that the dollar value of mental health benefits has decreased by 54 percent since 1988 (2). Although benefit levels have important implications for service utilization (6), the costs and use of mental health services have been shown to be more strongly associated with managed care practices than with benefit levels (7).

Employers that have implemented unlimited access to mental health for employees and their dependents have contained costs by using managed care strategies that result in lower costs and utilization (8,7). These strategies include restricting the use of inpatient and outpatient treatment, reducing payments to providers, increasing the use of nonphysician providers, using gatekeepers, and providing psychopharmacologic treatment instead of psychotherapy (3). Although most research shows that the use of any mental health care (especially outpatient care) increases after the implementation of managed behavioral health care (8,7), there is concern that managed care delivery systems may constrain care by offering rewards for undertreatment (9), adversely affecting access, quality, and outcomes.

This study assessed the extent to which financial considerations—such as managed care limitations, the patient's personal finances, and limitations inherent in a public system of care—affected the provision of "optimal" treatment as reported by psychiatrists in routine clinical practice. The data are based on a large national sample of psychiatric patients for whom psychiatrists reported whether treatment had been adversely affected by financial considerations in terms of a lower frequency of visits, a shorter duration of treatment, or a deviation from the treatment or medication that the psychiatrist would optimally have liked to provide.

Methods

This study used data from the 1997 American Psychiatric Practice Research Network (PRN) study of psychiatric patients and treatments, which generated nationally representative data on psychiatric patients treated by members of the American Psychiatric Association (APA). The study methods have been described previously (10) and are summarized here.

A total of 417 PRN member psychiatrists participated in the PRN study, for a response rate of 79 percent. The psychiatrists were randomly assigned a start day and time to complete a detailed data-collection instrument for three patients randomly preselected from a patient log; data for 1,228 patients were generated. Thirty-nine percent of the psychiatrists were randomly selected and recruited from the APA membership, and 61 percent were self-selected volunteers. Analytic comparisons of 78 sociodemographic and practice variables indicated that PRN members are representative of the APA membership, reflecting a majority of psychiatrists in the United States (10). Four of these variables showed statistically significant differences, which were accounted for in the sampling weights to enable national estimates to be generated.

The study collected detailed sociodemographic, diagnostic, clinical, treatment, and health plan data on the patients. Design-based significance tests (Wald's chi square tests and Wald's F tests) were used to examine differences in whether financial considerations affected the provision of optimal treatment across the sociodeomographic, clinical, treatment setting, and health plan variables as well as psychiatrist sociodemographic, training, and practice variables obtained from the APA membership database. Logistic regression was used to test all variables associated with whether financial considerations affected treatment (p=.25) to identify factors for which the association was strongest, for inclusion in the final model. A significance level of .05 was used for all other tests. SUDAAN software was used to adjust for the sampling design and develop weighted nationally representative estimates.

Results

Psychiatrists reported that financial considerations affected optimal treatment for 33.8 percent of the patients. For 23.4 percent of patients, financial considerations were associated with a lower frequency of visits than the psychiatrist would have liked to provide; for 16.1 percent, the duration of treatment was shorter; for 15.2 percent, a less optimal form of treatment was provided; and for 8.8 percent, a different medication was selected than the psychiatrist would have preferred.

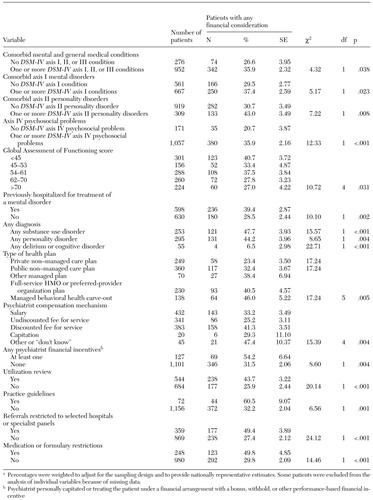

No statistically significant differences were found in whether financial considerations affected optimal treatment by sociodemographic characteristics, treatment setting variables, or psychiatrist characteristics. However, most of the clinical and diagnostic variables and health plan variables were associated with an effect of financial considerations on optimal treatment provision (Table 1).

Psychiatrists were more likely to report that financial considerations affected treatment for patients with comorbid axis I or II disorders than for patients who did not have those disorders. Financial considerations were reported to affect a significantly higher proportion of patients with a diagnosis of any substance use or personality disorder. Only 6.5 percent of patients with a diagnosis of delirium or other cognitive disorder were reported to have had their treatment adversely affected by financial considerations. Patients with lower scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), psychosocial problems, or a history of psychiatric hospitalization were significantly more likely to have had their treatment affected by financial considerations.

Seven health plan variables were associated with an effect of financial considerations on provision of optimal treatment. The effect was greater for patients in carved-out behavioral health plans, full-service health maintenance organizations, or preferred-provider organizations and for patients whose psychiatrist received a discounted fee for service.

Patients of psychiatrists with performance-based financial incentives were also more likely to have their treatment influenced by financial considerations. Patients whose treatment was subject to utilization review, incentives to use treatment guidelines, restrictions on referrals to selected hospitals and specialist panels, and restrictions on which medications could be prescribed also were more likely to have their treatment affected by financial considerations.

Six variables in the regression model were associated with a greater likelihood that the psychiatrist would report that financial considerations had adversely affected treatment provision: having a substance-related disorder (odds ratio [OR]=1.8; 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.2 to 2.6), having a personality disorder (OR=1.7, CI=1.1 to 2.4), having a GAF score of less than 60 (OR=1.7, CI=1.2 to 2.3), being subject to a formulary (OR=1.7, CI=1.1 to 2.6), and having referrals restricted to selected hospitals or specialist panels (OR=2.2, CI=1.6 to 3.2). Patients with delirium or other cognitive disorders were 85 percent less likely to have had their treatment adversely affected by financial considerations (OR=.15, CI=.1 to .4).

Discussion and conclusions

This study was limited by its use of a single, cross-sectional database that relied on subjective, psychiatrist-reported assessments of whether financial considerations affected the provision of optimal treatment. The data were not sufficiently detailed to allow examination of how financial considerations specifically affected treatment or to characterize the specific types of financial constraints.

The psychiatrists reported that financial constraints—such as managed care limitations, the patient's personal finances, or limitations inherent in a public system of care—resulted in the provision of less optimal treatment for 33.8 percent of patients. Patients were more likely to have their treatment adversely affected by financial considerations if they were more severely ill; if they had a comorbid mental health or substance use disorder, personality disorder, or psychosocial problem; or if they received treatment through a managed care plan.

The fact that the effect of financial considerations was greater for patients with substance use and personality disorders may reflect coverage limitations and exclusions for these disorders or the fact that these disorders may require long-term treatments that do not lend themselves to short-term therapies with narrow treatment objectives. The greater effect of financial considerations among managed care patients may reflect limitations on the type, intensity, or duration of treatment as a result of benefit levels or utilization management. This finding may also reflect differences between patients: psychiatrists in managed care plans may treat patients who are more severely ill and who thus require more intensive treatment and are more likely to exhaust their benefits. However, after adjustment for severity of illness, two managed care variables—being subject to a formulary and having referrals restricted to selected hospitals or specialist panels—were still associated with an effect of financial considerations on the provision of optimal treatment.

These results suggest that longitudinal research is needed to more rigorously characterize the specific financial considerations and how they affect treatment, such as which medications or other specific treatments were substituted or changed and the quality and outcomes of care ultimately provided.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Harold Alan Pincus, M.D., and Deborah A. Zarin, M.D., are co-principal investigators of the Practice Research Network, whose members contributed their time to participate in this study.

Dr. West is director of the American Psychiatric Practice Research Network, American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education, 1400 K Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20005 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Pingitore is an affiliated investigator at the Center of Mental Health Services Research at the University of California, Berkeley. Dr. Zarin is director of the technology assessment program of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; at the time of this study she was deputy medical director in the office of research at the American Psychiatric Association.

|

Table 1. Clinical and health plan variables associated with whether psychiatrists reported that financial considerations adversely affected "optimal" treatment for a national sample of 1,228 patientsa

a Percentages were weighted to adjust for the sampling design and to provide nationally representative estimates. Some patients were excluded from the analysis of individual variables because of missing data.

1. Buck JA, Umland B: Covering mental health and substance abuse services. Health Affairs 16(4):120-126, 1997Google Scholar

2. Health Care Plan Design and Cost Trends:1988-1997. Washington, DC, Hay Group, 1998Google Scholar

3. Findlay S: Managed behavioral health care in 1999: an industry at a crossroads. Health Affairs 18:116-124, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Jensen GA, Morrisey MA, Gaffney S, et al: The new dominance of managed care: insurance trends in the 1990s. Health Affairs 16(1):125-136, 1997Google Scholar

5. Sturm R, Pacula RL: Mental health parity and employer-sponsored health insurance in 1999-2000: I. limits. Psychiatric Services 51:1361, 2000Link, Google Scholar

6. Weissman E, Pettigrew K, Sotsky S, et al: The cost of access to mental health services in managed care. Psychiatric Services 51:664-666, 2000Link, Google Scholar

7. National Advisory Mental Health Council: Parity in Financing Mental Health Services: Managed Care Effects on Cost, Access, and Quality. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1998Google Scholar

8. Sturm R, McCulloch J, Goldman W: Mental health and substance abuse parity: a case study of Ohio's state employee program. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 10:129-134, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Frank RG, Morlock LL: Managing Fragmented Public Health Services. New York, Milbank Memorial Fund, 1997Google Scholar

10. Pincus HA, Zarin DA, Tanielian TL, et al: Psychiatric patients and treatments in 1997: findings from the American Psychiatric Practice Research Network. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:441-449, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar