Clinical Characteristics of Youths With Substance Use Problems and Implications for Residential Treatment

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Despite high rates of dual diagnosis among children and adolescents and evidence that adults with coexisting substance use disorders require specialized services, many children are placed in residential settings and are offered uniform service packages regardless of their individual clinical profiles. The authors examined the rate of substance use problems in a sample of children and adolescents with severe emotional or behavioral disturbances who were in residential treatment. Differences in clinical characteristics and placement outcomes between children with and without coexisting substance use disorders were evaluated. METHODS: This retrospective study analyzed clinical data obtained by chart review using the Child Severity of Psychiatric Illness, a rating scale for symptom severity. The study subjects were 564 children and adolescents in residential treatment and state custody in Florida and Illinois who had serious emotional or behavioral disturbances. RESULTS: Twenty-six percent of boys and 37 percent of girls had substance use problems in addition to serious emotional or behavioral disturbances. Residents with co-occurring substance use disorders were significantly more likely than those with serious emotional or behavioral disturbances only to be at risk for suicide, elopement from residential placement, delinquent behavior, and institutional discharge placement. CONCLUSIONS: Children and adolescents with coexisting substance use problems require individualized service packages to address their greater need for supervision and higher rate of risk behaviors and to facilitate community discharge placements.

Substance use is once again a growing problem among children and adolescents (1,2,3). Survey results showed a sharp resurgence in adolescent substance use disorders during the 1990s (3,4). Recent epidemiologic research shows that although the use of some drugs has declined among children and adolescents, the use of alcohol and other drugs continues to increase (1,5). Only a subset of youths who report substance use meets criteria for DSM diagnoses of substance use disorders. In community samples, the proportion of youths who meet criteria for DSM-IV diagnoses of substance use disorders ranges from 3 percent to 16 percent, depending on age, gender, and substance (3,6,7). Rates are highest among older adolescents, among males, and for alcohol and marijuana use disorders (3).

Among children and adolescents, substance use can produce disinhibition, lethargy, hyperactivity, agitation, somnolence, hypervigilance, decreases in attention span and perception, difficulty coping, impairments in psychosocial and academic functioning, and disruption of thought processes (8,9,10). These problems can impede development and facilitate problematic behaviors such as risk taking, aggression, and suicidal behavior, which in turn can increase rates of motor vehicle accidents, homicide, and suicide (8,11,12,13).

Substance use problems may co-occur with depressive, conduct, and anxiety disorders (13,14,15,16). Twenty-five to 61 percent of adolescents with substance use disorders also have major affective disorders (15,16,17). Comorbidity can exacerbate the problems associated with major affective disorders; for example, substance use appears to increase the risk of suicidal behavior among adolescents with coexisting depressive disorders (18,19).

To complicate matters, substance use disorders are underreported by adolescents and may be harder to detect among children and adolescents than among adults (3,13). Substance use disorders complicate the delivery of mental health services to adults and also affect treatment outcomes by increasing instability, resistance to treatment, noncompliance, and recidivism (16,18). For this reason, adults with substance use disorders and other mental disorders require specialized services to address the confluence of factors that arise from comorbidity. However, research is lacking on the service needs of children and adolescents with dual diagnoses.

Use of residential services is common in the treatment of children and adolescents, and residential placements are common in child welfare (20,21). Residential placements may be in large residential treatment programs, group homes, supervised independent living facilities, or specialized residential treatment programs, such as programs for youths who are sexual offenders (22).

Many of the children who populate residential treatment settings have long, unstable residential histories. From residential treatment, children may move on to other institutionalized settings, such as hospitals, detention centers, and additional residential placements. Alternatively, they may be discharged to community settings, such as foster homes and adoptive homes. In some cases, children are discharged when they run away from residential placements.

Many children are placed in residential settings that offer the same service packages indiscriminately, regardless of individual clinical profiles (22). Recent research has suggested a shift in focus from linking children and adolescents with mental health services to selecting the appropriate service for each child's particular problem from a range of options (23).

To accomplish this goal, it is important to improve our understanding of the needs of children and adolescents with dual diagnoses in residential treatment. In this study we looked at the prevalence of coexisting substance use problems in a sample of children and adolescents in residential treatment in two states. We compared the rates of different clinical characteristics of youths with and without dual diagnoses and examined the relationship between coexisting substance use problems and the type of discharge placements. On the basis of our findings, we make recommendations for incorporating diagnostic information into treatment planning for children and adolescents.

Methods

We used data collected retrospectively from the charts of children and adolescents in residential treatment in Florida and Illinois between 1987 and 1996. We analyzed these data to determine the rate of coexisting substance use problems and the incidence of other clinical risk factors among children and adolescents with and without coexisting substance use problems. We also examined differences in the types of discharge placements among children and adolescents in Florida with and without substance use problems.

Data from the two states were aggregated so that rates of severe emotional or behavioral disturbances, substance use problems, and dual diagnosis could be reported for the entire group. We found no significant differences in these rates between the samples before aggregation.

Study subjects

In Florida, a random sample of 450 children and adolescents was drawn from 15 residential treatment centers that bill Medicaid for services and from an additional site that was interested in exploring Medicaid billing. At each Medicaid site, a random sample of 30 children and adolescents was selected from cases in which Medicaid had been billed for any services during the previous year. At the non-Medicaid site, a random sample of 30 cases was selected.

In Illinois, a random sample of 321 children and adolescents was drawn from 17 residential placements for wards of the state of Illinois. These 17 providers were drawn randomly from a list of all Department of Child and Family Services providers in Illinois. The Illinois sample was stratified into three tiers according to program size: large, more than 50 children in residence; medium, 20 to 50 children; and small, fewer than 20 children. At each of the large sites, a random sample of 30 Department of Child and Family Services cases was examined. At the medium programs, random samples of 20 files were drawn. At the small programs, samples of ten to 12 files were randomly selected.

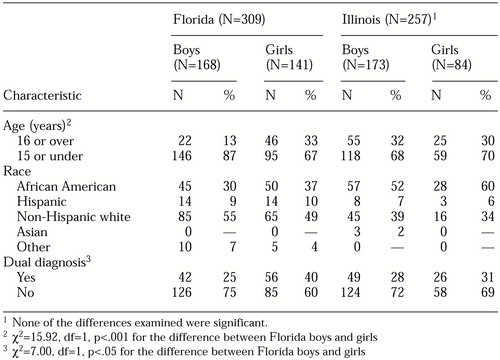

In both states, samples were obtained by random selection of children and adolescents from a list of cases served by the agencies during the previous 12 months. None of the residential programs selected for participation included specialized substance abuse treatment programs. Table 1 summarizes demographic and clinical characteristics of the children in each state.

Measures

Childhood Severity of Psychiatric Illness. The Childhood Severity of Psychiatric Illness (CSPI) (24) was used to rate children's mental health and substance use problems, level of risk, and other clinical characteristics on the basis of retrospective chart data. The CSPI integrates information contained in each chart to summarize psychiatric symptoms, risk behaviors, and functioning as well as factors that influence the degree of pathology in these areas (22,25). When used retrospectively, the CSPI provides a description of the type and level of mental health care needs of children and adolescents as they are documented by service providers (26).

Previous studies have indicated that the CSPI output is strongly correlated with clinical interview data and with other measures, such as the Achenbach's Child Behavior Checklist (24). After the raters have been trained, the reliability of the CSPI is generally greater than .85. Pilot studies have shown the CSPI to be a useful decision-support tool and an accurate measure of children's mental health care needs, use of mental health care services, and outcomes (24).

Each CSPI item is rated on a 4-point scale. The anchor points on the scale (0, 1, 2, and 3) represent progressively increasing levels of disturbance in the child's functioning in each area. In general, a rating of 0 indicates no evidence of a problem or cause for clinical concern on a given dimension; a rating of 1 indicates a mild degree of disturbance; 2, a moderate degree; and 3, an acute or severe degree of disturbance and a need for immediate intervention.

This study used the "symptoms" and "risk factors" dimensions of the CSPI. Items that make up the symptoms dimension correspond to five broad categories: emotional disturbance, conduct disturbance, neuropsychiatric (psychotic) disturbance, oppositional behavior, and impulsivity. The risk factors dimension takes into account the recency and acuteness of each risk behavior, with higher ratings assigned to more recent and acute risk.

Type of discharge placements. Discharge placements were categorized as being community or institutional settings. Foster homes, adoptive homes, and relatives' homes constituted community discharge placements, whereas hospitals, residential treatment, and detention centers were classified as institutional placements.

Procedures

All data were obtained from the children's files at the residential sites. Charts were reviewed in both states by trained psychology graduate and undergraduate research assistants under the direction of the project coordinator. The interrater reliability was high (kappa=.88). Basic demographic information, including age, gender, length of stay in the residential program, history of psychiatric hospitalization, and diagnosis, was collected as well.

CSPI ratings within the symptoms dimension were used to determine whether children or adolescents had substance use problems or serious emotional or behavioral disturbances. The CSPI is not a diagnostic tool but rather a method for assessing needs and strengths. Thus we established cutoff points for each item to represent three levels of disturbance. A child or adolescent was rated as having severe emotional or behavioral disturbances if he or she had a score of 2 or above on any of the symptom dimensions of the CSPI. A child or adolescent was categorized as having substance use problems if he or she had a score of 1 or above on the substance abuse item of the CSPI.

We had two reasons for using a lower cutoff on the substance abuse item. First, because research suggests that substance use is vastly underreported by adolescents, we believe it is more reasonable to include all of those for whom there is even some indication of a problem (3). Second, all substance use by adolescents is illegal. Although adolescents with varying degrees of substance use problems do have different treatment requirements, the purpose of this study was to distinguish between the needs of adolescents with and without any substance use problems. If the child or adolescent had severe emotional or behavioral disturbances in addition to a positive rating for substance use problems, he or she was classified as having coexisting substance use, or a dual diagnosis.

CSPI ratings within the risk factor dimension were used to categorize clinical characteristics of the children and adolescents. Ratings of 1 or above on items related to suicidality, elopement, crime or delinquency, adjustment to trauma, medical problems, and school, family, and peer dysfunction constitute positive scores on these items.

Data analysis

On the basis of research suggesting that clinical profiles of adolescents with substance use problems vary with gender and age, data from boys and girls, older subjects (age 16 and over), and younger subjects (age 15 and under) were analyzed separately (3,21,27). Differences in risk factors and other clinical characteristics between children and adolescents with and without dual diagnoses were evaluated by using the chi square test with continuity correction.

Results

Overall, 566 individuals (72 percent of the total population of the two groups) met criteria for severe emotional or behavioral disturbances. Of these, 225, or 40 percent, were girls. Of the 448 individuals for whom racial or ethnic information was available, 180, or 40 percent, were African American; 211, or 47 percent, were non-Hispanic white; 39, or 9 percent, were Hispanic; and 15, or 3 percent, belonged to other racial or ethnic groups. A majority of the study subjects (418, or 74 percent) were under the age of 16.

Overall, 173, or 31 percent, of the children were rated positively for substance use problems in addition to serious emotional or behavioral disturbances—that is, they had dual diagnoses. Among girls aged 16 or older, 32, or 45 percent, had a dual diagnosis, whereas 50, or 33 percent, of the younger girls had a dual diagnosis. This difference was not statistically significant. Thirty-one, or 40 percent, of the boys aged 16 or older and 60, or 23 percent, of the younger boys were rated as having both severe emotional or behavioral disturbances and substance use problems (χ2=8.49, df=1, p=.004).

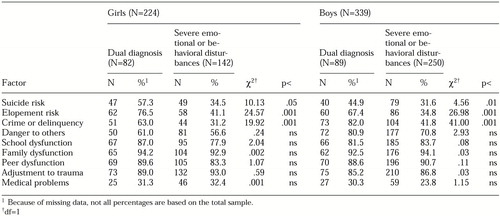

Table 2 shows the differences in risk factors and other clinical characteristics between the children and adolescents in our sample with severe emotional or behavioral disturbances with and without dual diagnoses. Girls with dual diagnoses were significantly more likely than those without dual diagnoses to have problems with suicidality, elopement, and crime or delinquency. Girls with and without dual diagnoses had similarly high rates of problems with dangerousness; family, school, and peer functioning; adjustment to trauma; and health. Boys with dual diagnoses were significantly more likely than those without dual diagnoses to have more severe problems in the areas of suicidality, elopement, and crime or delinquency.

Discharge placement data were available for 91, or 72 percent, of the 126 children and adolescents with severe emotional or behavioral disturbances who had been discharged from the Florida residential placements. No significant differences were found in the rate of dual diagnosis between discharged clients for whom these placement data were available and those for whom they were not.

Among children and adolescents for whom placement data were available, girls with dual diagnoses were significantly less likely than those without to be discharged to community placements—their parents' home, an adoptive home, or foster care. Of the girls with dual diagnoses, 11, or 44 percent, were placed in the community, compared with 23, or 85 percent, of those without dual diagnoses (χ2=7.99, df=1, p=.005). Girls with dual diagnoses were significantly more likely than those without to be discharged to institutional placements—for example, the hospital, residential treatment, or a detention center. Of the girls with dual diagnoses, 14, or 56 percent, were discharged to institutional placements, compared with 4, or 15 percent, of those without dual diagnoses. No significant difference was found in placements between boys with and without dual diagnoses.

Discussion

Among the most needy children in the child welfare system, those with dual diagnoses present a unique challenge to service providers. Although all the children and adolescents in our sample had high rates of serious emotional or behavioral disturbances, those with coexisting substance use problems—that is, those with dual diagnoses—were significantly more likely to be at risk of suicide, elopement, crime or delinquency, and discharge to institutional placements. This finding suggests that children and adolescents with dual diagnoses constitute a distinct group with distinct mental health treatment needs.

Both groups of children and adolescents had high rates of problems functioning in school, at home, and among peers; high rates of problems adjusting to trauma; and relatively low rates of medical problems. However, rates of risk behavior were higher among children and adolescents with dual diagnoses than among their peers who did not engage in substance use. These higher rates are reflected in higher ratings for suicidality and higher rates of elopement and delinquency among children and adolescents with coexisting substance use problems.

The findings related to higher rates of crime and delinquency are not surprising given that adolescent substance use may occur as part of a constellation of rebellious behaviors. Rates of elopement and suicidality are of more concern, because they suggest that residential treatment may not be fulfilling its promise to children with substance use problems.

Children and adolescents with dual diagnoses also may have poorer outcomes in residential treatment. In addition to having higher rates of elopement and suicidal behavior, residents with coexisting substance use problems were more likely than those without to remain in institutional settings. The illegality of youth substance use, the higher risk of dangerous behavior, and the higher rate of elopement all increase the likelihood that children and adolescents with dual diagnoses will be placed in institutional rather than community settings. However, such placement can perpetuate the alienation experienced by children in state custody and impede reintegration into the community. Services are needed within residential treatment programs to address substance use problems and to provide specialized treatment to reduce the risk of poor outcomes and to increase the rate of community placements.

It is interesting that rates of problems adjusting to trauma did not differ significantly between youths with and without dual diagnoses, because etiological hypotheses have suggested links between problems in this area and adolescent substance use. Although previous research has suggested that childhood trauma may be one precipitant to child and adolescent substance use, having significant difficulties coping with trauma was not associated with a higher rate of substance use problems in this sample (11,28). There are several possible explanations for this finding. First, other factors may serve as precipitants to substance use problems. Familial and genetic explanations are likely, because children and adolescents in the child welfare system may have learned or inherited this behavior from parents who abused drugs or alcohol. This finding may also be explained by the fact that the rate of adjustment problems, along with the rate of family dysfunction, was very high among all the groups in our sample. Such high rates obscure the variation that might occur in these dimensions among youths with and without substance use disorders.

Implications for treatment and policy

These findings should prompt treatment planners and providers to rethink the common practice of providing uniform treatment protocols to children and adolescents in residential placements. Mental health treatment needs as well as supervision and monitoring needs depend on individual clinical profiles. The development of individualized treatment plans calls for in-depth assessment, ongoing monitoring, and increased funding to improve the appropriateness of treatment alternatives provided in residential placements.

The fact that children and adolescents with coexisting substance use disorders did not have significantly higher rates of school, family, and peer dysfunction underscores the difficulties in detecting these disorders. Service providers should screen for substance use disorders among children and adolescents who arrive at residential treatment facilities and should monitor the progression of substance use when a low level of risk is initially detected. In addition, higher rates of risk behaviors among youths with dual diagnoses might indicate a need for a higher level of supervision and monitoring.

In-depth assessment of the substance use problems of children and adolescents in residential treatment is needed to clarify the level of substance use, the level of clinical risk, the cause of each child's substance use disorder, and the specific nature of treatment needs. Treatment will vary according to the severity and duration of substance use problems—youths who report infrequent, early use will receive less intensive interventions than those with more severe, chronic substance use histories (2).

Successful substance use treatment also must take into account the specific nature of each patient's comorbidity (29). Therefore assessments must address not only the disorders that coexist with substance use but also the order in which these disorders developed (7). Guidelines for in-depth assessment of the substance use treatment needs of children and adolescents have been developed by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and guidelines for levels of intervention with adolescents have been developed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (30,31).

In addition to efforts to comprehensively assess the needs of adolescents with substance use problems in residential placements, more effort is needed to shift the paradigm of providing uniform treatment within group modalities to adolescents in residential placements. A growing body of research suggests that treatment within the large group settings of many residential treatment centers can exacerbate substance use problems (32). Peer "deviancy training," or the pattern of positive peer responses that reinforce delinquent behavior, is associated with subsequent increases in substance use, delinquency, and violence as well as adjustment difficulties in adulthood (32).

Alternatives will depend on policies that encourage the development of new programs to assess and treat coexisting substance use disorders in residential treatment settings. Additional funding will be needed to develop these programs and to provide individual attention to children and adolescents with coexisting substance use problems in residential placements.

Limitations

When interpreting these findings, it is important to keep in mind some of the limitations of this study. First, because state custody and residential treatment are often the last in a long line of alternatives for troubled children and adolescents, our sample consisted of children and adolescents whose circumstances and problems were more severe than those in the general or clinical populations. The severity of the psychiatric problems in this population may limit the generalizability of these findings to other, less severely ill, groups of children and adolescents. This severity also means that we were less likely to observe significant differences between groups with and without dual diagnoses on dimensions in which both groups had high rates of problems, such as family dysfunction and adjustment to trauma.

In addition, we reported the discharge placements for only a portion of discharged patients from residential treatment facilities in Florida. Many of the patients whose cases we reviewed had not been discharged, and discharge placement data were not available for all discharged patients. Although the rate of substance use was comparable among discharged patients with and without placement data, it is likely that some of the discharged patients for whom we could not collect placement information were children or adolescents who were unaccounted for because of elopement.

Finally, more research is needed to address the outcomes of residential treatment for children and adolescents with coexisting substance-related disorders. These findings suggest that some adolescents or children with dual diagnoses may need more specialized and intensive services than do some other groups of clients, but this need is still poorly understood. To fully explore this issue, a more thorough analysis of children's clinical profiles and their associated treatment outcomes is needed.

Conclusions

Given the number of children with substance use problems in residential placements, our findings are cause for heightened concern. The prevalence of substance use problems and the relatively poor dispositional outcomes observed in this study call for a careful examination of the manner in which children with dual diagnoses receive mental health treatment in residential placements.

Elevated risk among children and adolescents with dual diagnoses in residential placements calls for policies that encourage the development of individualized treatment protocols. These protocols should be based on in-depth assessments and should closely correspond to the child's clinical needs. For children and adolescents with serious emotional or behavioral disturbances and substance use problems, this approach may involve providing screening, assessment, increased supervision, individual attention, and specialized substance abuse treatment.

Placement in residential treatment often represents one point in a sequence of homes for children who have unstable residential—and developmental—histories. For these children, residential treatment settings can provide stability and consistency. To ensure that residential treatment is used appropriately and effectively, researchers should continue to examine the need for and the effectiveness of individualized, needs-based services for children and adolescents with substance use problems in residential placements.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration and the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services. The participation of Dr. Weiner was supported through a fellowship from the National Institute of Disability Rehabilitation and Research. The participation of Ms. Abraham was supported through a fellowship from the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. The authors thank Frank Reyes, B.A., Celeste Tanzy, B.A., Peter Tracy, M.A., Courtney West, B.A., and Cassandra Kisiel, Ph.D., for their assistance.

Dr. Weiner is a mental health services researcher and research consultant in Chicago. When this work was done she was a fellow at the Institute for Health Services Research and Policy Studies at Northwestern University in Chicago. Ms. Abraham is a National Research Service Award Fellow in the Mental Health Services and Policy Program at the Institute for Health Services Research and Policy Studies at Northwestern University in Chicago. Dr. Lyons is professor and director of the mental health services policy program in the division of psychology of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago. Send correspondence to him at Wieboldt Hall, Room 717, 339 East Chicago Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60611 (e-mail, [email protected]). An earlier version of this paper was presented as a poster at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association held August 10-14, 1999, in Boston, Massachusetts.

|

Table 1. Demographic and diagnostic characteristics of 566 children and adolescents with severe emotional or behavioral disturbances in residential treatment and Illinois

|

Table 2. Rates of clinical risk factors among children in residential treatment with severe emotional or behavioral disturbances with and without substance use problems, as measured by the Childhood Severity of Psychiatric Illness

1. Johnston L, O'Malley P, Bachman J: Results on Drug Use From the Monitoring the Future Study, 1997. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1997Google Scholar

2. Winters K: Treating adolescents with substance use disorders: an overview of practice issues and treatment outcome. Substance Abuse 20:203-225, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

3. Weinberg NZ, Rahdert E, Colliver JD, et al: Adolescent substance abuse: a review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 37:252-261, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Johnston L, O'Malley P, Bachman J: Monitoring the Future: National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings, 1999. NIH pub no 00-4690. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2000Google Scholar

5. Substance abuse: a national challenge: prevention, treatment, and research at HHS. DHHS fact sheet. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, Dec 17, 1999Google Scholar

6. Harrison PA, Fulkerson JA, Beebe TJ: DSM-IV substance use disorder criteria for adolescents: a critical examination based on a statewide school survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:486-492, 1998Link, Google Scholar

7. Kandel DB, Johnson JG, Bird HR, et al: Psychiatric comorbidity among adolescents with substance use disorders: findings from the MECA study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:693-699, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bukstein O, Work Group on Quality Issues: Summary of the practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with substance use disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 37:122-126, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR: Adolescent psychopathology: III. the clinical consequences of comorbidity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:510-519, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Mezzich AC, Tarter RE, Kirisci L, et al: Coping capacity in female adolescent substance abusers. Addictive Behaviors 20:181-187, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Armentano ME: Assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of the dually diagnosed adolescent. Substance Abuse 42:479-490, 1995Google Scholar

12. Grilo CM, Becker DF, Walker ML, et al: Psychiatric comorbidity in adolescent inpatients with substance use disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:1085-1091, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Parrish S: Adolescent substance use: the challenge for clinicians. Alcohol 11:453-455, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Grilo CM, Becker DF, Fehon DC, et al: Conduct disorder, substance use disorders, and coexisting conduct and substance use disorders in adolescent inpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:914-920, 1996Link, Google Scholar

15. King C, Ghaziuddin N, McGovern L, et al: Predictors of comorbid alcohol and substance abuse in depressed adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:743-751, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Myers M, Brown SA, Mott MA: Preadolescent conduct disorder behaviors predict relapse and progression of addiction for adolescent alcohol and drug abusers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 19:1528-1536, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Stowell JR, Estroff TW: Psychiatric disorders in substance abusing adolescent inpatients: a pilot study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 31:1036-1040, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Piazza NJ: Dual diagnosis and adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Substance Use and Misuse 31:215-223, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, et al: Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:181-189, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

20. Lyons JS, Terry P, Petersen J, et al: Outcome trajectories in residential treatment of adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, in pressGoogle Scholar

21. Whitmore EA, Mikulich SK, Thompson LL, et al: Influences on adolescent substance dependence: conduct disorder, depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and gender. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 47:87-97, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Lyons JS, Mintzer LL, Kisiel CL, et al: Understanding the mental health needs of children and adolescents in residential treatment. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 29:582-587, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

23. Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Mezzich AC: Multivariate typology of adolescents with alcohol use disorder. American Journal on Addictions 6:150-159, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Lyons JS: Severity of Psychiatric Illness Manual: Child and Adolescent Version. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, 1998Google Scholar

25. Leon SC, Lyons JS, Uziel-Miller ND, et al: Psychiatric hospital utilization of children and adolescents in state custody. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:305-310, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Lyons JS, Howard KI, O'Mahoney MT, et al: The measurement and management of clinical outcomes in mental health. New York, Wiley, 1997Google Scholar

27. Cohen P, Cohen J, Kasen S, et al: An epidemiological study of disorders in late childhood and adolescence: I. age- and gender-specific prevalence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 34:851-867, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Wilcox JA, Yates WR: Gender and psychiatric comorbidity in substance abusing individuals. American Journal on Addictions 2:202-206, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Kaminer Y, Blitz C, Burleson JA, et al: Measuring treatment process in cognitive-behavioral and interactional group therapies for adolescent substance abusers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 186:407-413, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with substance use disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:140S-156S, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Treatment of Adolescents with Substance Use Disorders. TIPS 32. Rockville, Md, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 1999Google Scholar

32. Dishion TJ, McCord J, Poulin F: When interventions harm: peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist 54:755- 764, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar