Improving Understanding of Research Consent Disclosures Among Persons With Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The objective of this study was to evaluate alternative procedures for improving the understanding of research consent disclosures by persons who have mental illness. METHODS: Three groups participated in the study: persons with schizophrenia (N=79), persons with depression (N=82), and a healthy control group (N=80). The participants were guided through an informed consent process in which two factors were manipulated. One was the structure of the disclosure form; either a typical disclosure form involving standard dense text was used, or a graphically enhanced form was used. The other was the interpersonal process: the presence or absence of a third-party facilitator, with iterative feedback given to participants for whom a facilitator was not present. Participants' understanding of the disclosure was assessed with the use of recall tests that involved paraphrasing and recognition tests that involved multiple choice. RESULTS: The mean understanding scores did not differ significantly between the depression and control groups, and the mean scores of the schizophrenia group were significantly lower than those of the other two groups. Neither the graphically enhanced consent disclosure form nor the presence of a third-party facilitator was associated with improved understanding. The use of iterative feedback was associated with improvement in comprehension scores in all groups. CONCLUSIONS: The use of a feedback procedure in the consent disclosure process during the recruitment of persons who are mentally ill may be a valuable safeguard for ensuring adequate understanding and appropriate participation in research.

Psychiatric patients may experience a variety of symptoms that impair their capacity to comprehend informed consent disclosures for research studies. The National Bioethics Advisory Commission has noted (1) that although "the mere diagnosis of a mental disorder does not imply a lack of decision making capacity," it is widely acknowledged that "persons with fluctuating and/or limited capacity present serious problems of assessment." The inappropriate inclusion in research studies of individuals who are incompetent to make decisions about participation may expose these persons to unwarranted risks; conversely, the inappropriate exclusion of competent and willing individuals affronts individual dignity and autonomy and may bias research results (2).

To minimize these risks, it is important that procedures be developed that accurately and optimally assess the comprehension of research consent disclosures by potential research participants. In this study we evaluated several procedures designed to enhance the understanding by mentally ill persons of research consent disclosures.

Several writers have suggested that a third party, described in the literature as a consent auditor (3), a neutral educator (4), or a research intermediary (5), be involved as a means of facilitating prospective participants' understanding of consent disclosures. Although the concept of a facilitator appears to have some promise, little empirical work has been done to define the facilitator's role or to determine what methods are successful in enhancing comprehension.

Ample research has shown that consent disclosures that require unrealistically high reading levels (6,7,8,9) or that contain excessive clinical jargon (10) are more difficult to comprehend than more simple disclosures. Other studies have suggested that the graphic layout of the disclosure form may influence comprehension (11). For example, comprehension may be improved by the use of full sentences—such as "You do not have to take part in this study if you do not want to"— that identify a paragraph's key point, rather than simple topical headings such as "Voluntary Participation." Comprehension could also be improved by the use of bullet formatting that highlights important information that is usually buried in narrative text.

Another potentially important contextual variable is the task used to evaluate understanding. Although most investigators have used recall measures—for example, paraphrasing—to assess understanding, an alternative is to use objective measures, such as multiple-choice or true-false tests. Informed consent studies among elderly persons (12) and studies of mentally ill persons in the contexts of treatment decision making (13) and voluntary hospitalization (14) showed that comprehension was better when objective measures rather than recall measures were used.

Roth and Appelbaum (15) argued that "consent should be regarded not as an event but as a process," and that "sustained efforts should be made to inform subjects before concluding that they cannot understand. …" Subsequent studies among elderly persons (16,17) and people with schizophrenia (18,19) or depression (20) have shown that for many patients, corrective feedback or educational interventions may be effective in ameliorating initial difficulties in understanding consent disclosures.

In this hypothetical clinical trial we manipulated two aspects of the informed consent process: the structure of the consent form—typical versus graphically enhanced—and the presence or absence of a third-party facilitator. Each participant's understanding of a consent disclosure for a hypothetical medication trial was tested with use of both recall and recognition tests. For participants who were not exposed to a facilitator during the informed consent process, we also evaluated the impact of iterative feedback on the ultimate recognition score.

The participants were people who were receiving treatment for schizophrenia or depression and a healthy control group who were randomly assigned to experimental conditions. Against null hypotheses of no differences among diagnostic groups or experimental manipulations, our experimental hypotheses were that scores on understanding would be lower in the group with schizophrenia than in the other two groups; that scores on understanding would be higher among participants who received the graphically enhanced consent form; that scores on understanding would be higher when the consent process was mediated by a third-party facilitator; that scores on understanding would be higher for recognition than for recall tests; and that iterative feedback would improve the participants' understanding of consent disclosures.

Methods

Participants

A total of 241 adults aged 18 years or older participated in the study, which took place during 1997 and 1998. The clinical participants—that is, those who had either schizophrenia (N=79) or depression (N=82)—were recruited from mental health treatment facilities in west central Florida. The control group comprised 80 persons from a local jury venire who were awaiting the call to jury duty. All participants were compensated $10 for their time.

Stimulus materials

Two versions of the consent disclosure were used. The model for the typical consent form was a consent form from an actual medication trial that was obtained from the archives of the institutional review board of the University of South Florida. The typical form had discrete headings, such as "Purpose of the Study," to identify discrete issues. Information about each issue was presented in paragraph format. In contrast, the graphic version contained presentational enhancements that were recommended by a focus group of mental health care consumers, who reviewed sample disclosures that displayed a variety of possible graphic features—for example, different fonts and the use of bold or italic type—that could be used to emphasize important information.

A fictitious drug name—petrinone—was inserted in place of the original drug name, and, for each group, typical and graphic versions described petrinone as an experimental drug for the treatment of the relevant disorder. For the control group, heart disease was listed as the disorder being treated because it was considered to be a plausible disorder to which control participants could relate. The consent forms were otherwise identical in content.

Measures

Demographic and clinical measures. A brief questionnaire was used to elicit self-reported demographic information. Clinical measures included the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale-Anchored Version (BPRS-A) (21) and the Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) (22). The BPRS-A provides a global index of the severity of current psychopathology on the basis of clinical ratings, on a scale from 1 to 7, of 18 psychiatric symptoms on the basis of a brief interview. Possible scores thus range from 18 to 126, with higher scores indicating greater severity. The MMSE is a brief screening measure that evaluates areas of cognitive functioning, such as attention and memory. Scores on the MMSE range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating better functioning; a cutoff score of 24 is recommended for identifying cognitively impaired individuals.

Measures of understanding. Recall and recognition tests were constructed to test participants' understanding of the consent disclosure. The recall test contained open-ended questions that required a paraphrased response, and the recognition test used a multiple-choice format. Each test had a range of possible scores from 0 to 15, with higher scores indicating better understanding, and each tested for the same 15 elements.

Procedures

Clinical staff at participating treatment facilities identified potentially eligible participants—that is, those who met age and diagnostic inclusion criteria and who did not pose a threat to the trained research assistants who were to administer the protocol. Participants were self-identified; they volunteered in response to an announcement through the public address system. Informed consent was obtained from each participant according to procedures approved by the institutional review board of the University of South Florida.

Participants in each group were randomly assigned to receive either a standard consent process with feedback or a facilitated consent process and, within those conditions, either the typical or the graphic version of the consent form. Each participant completed the demographic questionnaire first. The consent disclosure and the tests of understanding were then presented—recall followed by recognition. Finally, the MMSE and the BPRS-A were administered.

For the participants who were exposed to the standard consent process with feedback, the research assistant assumed the role of the petrinone investigator, gave the participant a copy of the consent disclosure, and told the participant to follow along while the consent form was read aloud. The research assistant then encouraged the participant to ask questions or seek clarification of material that was not understood. The recall test was then administered, followed by the recognition test.

Any participant who did not attain a perfect score on the recognition test received feedback and was retested. The research assistant identified any sections of the consent form that contained information that the participant had not adequately understood. The research assistant then reread these areas of the form to the participant and retested the participant by using the entire recognition test. Two iterations of feedback and retesting were permitted, although a second iteration was not executed if the participant attained a perfect score after one iteration.

For participants who were exposed to the facilitated condition, one research assistant recruited the participant into the study and then left the room. Two other research assistants—assuming the roles of facilitator and petrinone investigator—entered the room to administer the consent disclosure. The same research assistant served as facilitator for all participants in the facilitated condition.

The facilitator introduced herself to the participant and the "investigator" and explained that her role was to help the participant understand the consent form. The consent form presented information in 13 discrete sections, including purpose, description, possible benefits, potential risks, and confidentiality. The facilitator used several strategies, developed in consultation with a mediation expert, in an effort to maximize participants' understanding. These strategies included interrupting the reading of the consent disclosure at the end of each section to ask the participant to state the main points of the section, to ask whether the participant had any questions about that section, and to urge the participant to seek clarification at that time rather than wait until the disclosure had been read in its entirety. When the consent disclosure was completed, the recall test of understanding was administered, followed by a single administration of the recognition test.

Statistical analyses

Before the statistical analyses were conducted, participants' scores on the MMSE and the BPRS-A were examined. Ten participants who had either schizophrenia or depression and whose MMSE scores were below the recommended cutoff of 24 were excluded from the analyses to reduce the effect of cognitive impairment on the results. Thus we were able to focus on the effect of other factors on dependent measures of understanding. Four participants in the control group whose BPRS-A scores were more than two standard deviations below the group mean were excluded to maximize the likelihood that the control group did not include individuals with acute psychiatric conditions. Thus a total of 227 participants were included in the analysis.

Independent variables included whether the participant was in the schizophrenia, depression, or control group; whether the typical or graphic version of the consent form was used; and whether the participant was exposed to the standard consent process with feedback or to the facilitated consent process. Dependent variables were scores on the recall and recognition tests. Thus the study used a 3 ×2 ×2 design—three diagnoses, two forms, and two processes—with two dependent variables. Analyses were conducted with SPSS, version 9.0.

Results

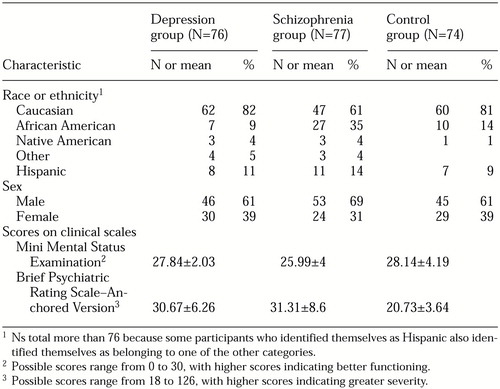

The overall research sample was predominately male (135 participants, or 59 percent) and Caucasian (178 participants, or 78 percent). Clinical and demographic information for the participants who were included in the analyses is presented by diagnostic group in Table 1. The distribution of Caucasian and African-American subjects differed across groups (χ2=17.7, df=2, 211 p<.001); African Americans were overrepresented in the schizophrenia group. The depression, schizophrenia, and control groups differed significantly in their scores on both the BPRS-A (F=61.95, df=2, 224, p<.001) and the MMSE (F=10.05, df=2, 224, p<.001).

The educational level of the patients in the control group was higher than that of the patients in the depression and schizophrenia groups. Whereas 31 percent of the control group reported having a college degree, only 6 percent and 12 percent of the depression and schizophrenia groups, respectively, reported this level of education. All the participants in the control group had graduated from high school, whereas 20 percent of the depression group and 18 percent of the schizophrenia group had not graduated from high school.

Differences in understanding

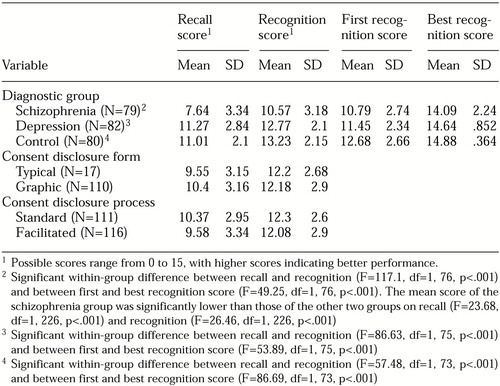

A statistically significant main effect was obtained for diagnosis (F=13.76, df=2, 215, p<.001). Significant differences were observed among groups in scores on both the recall test (F=6.87, df=2, 215, p<.001) and the recognition test (F=25.03, df=2, 215, p<.001). Post hoc comparisons showed that the mean recall and recognition scores of the control and depression groups were not significantly different. However, the mean score of the schizophrenia group was significantly lower than those of the other groups on both recall and recognition (Table 2).

Effect of graphic forms

Contrary to our experimental hypotheses, the use of a graphic format or the presence of a facilitator was not associated with improvements in comprehension. A significant interaction between diagnostic group and consent process was observed (F=3.06, df=2, 215, p<.049). Participants in the control and depression groups who were exposed to the facilitated consent process had somewhat higher recognition scores than those who received feedback only. In contrast, first recognition scores of participants in the schizophrenia group who were exposed to the standard disclosure process with feedback were higher than the scores of those who had a facilitator.

Recall compared with recognition

For the three groups combined, the mean±SD recall score (9.97±3.15) was significantly lower than the first recognition score (12.15±2.79) (F= 59.52, df=1, 215, p<.001). As shown in Table 2, scores were significantly higher in each group when understanding was measured by multiple choice (recognition) rather than by paraphrase (recall).

Effect of iterative feedback

Among the participants who received feedback, 25 of 38 (66 percent) in the depression group, 26 of 37 (73 percent) in the control group, and 28 of 36 (86 percent) in the schizophrenia group did not obtain a perfect score of 15 on the first recognition test and received up to two iterations of feedback and retesting. Each participant's highest score across iterations was indexed as his or her best recognition score. The mean first and best recognition scores for each group are shown in Table 2.

For all groups, a significant difference between first and best mean± SD recognition scores was observed (12.30±2.66 and 14.61±1.42, respectively) (F=94.69, df=1, 73, p<.001), indicating that understanding improved as a result of the intervention. The within-group comparisons shown in Table 2 indicate significant improvement from first to best recognition scores in all three groups.

Although the mean first recognition scores were significantly different across diagnostic groups (F=5.49, df=2, 108, p=.004), the mean best recognition scores did not differ significantly among groups. After the final iteration of feedback, only 6 of 36 participants in the schizophrenia group (17 percent), 3 of 38 participants in the depression group (8 percent), and 2 of 37 participants in the control group (5 percent) had not attained the maximum possible recognition score of 15.

Discussion

It was not surprising that the participants with a mental disorder in this study, particularly those who had schizophrenia, had difficulty understanding research consent disclosures. Similar results have been obtained in investigations of competence to make treatment decisions (13), competence to consent to voluntary hospitalization (23), and comprehension of research consent disclosures (19). Differences in understanding across diagnostic groups cannot be attributed to differences in educational level, because the schizophrenia and depressed groups were comparable in terms of education.

Additional results from this study provide important information about comprehension of consent disclosure that has not been examined systematically, whereas other findings replicate important outcomes of other studies. We evaluated two suggestions for enhancing comprehension that have not been studied extensively—the use of graphically enhanced consent forms and third-party facilitators who mediate the consent process. Although both of these approaches appear logical and conceptually sound, we found no evidence that either of them improved understanding. In fact, the interaction observed between diagnostic group and the type of consent process—standard compared with facilitated—suggests that the presence of a third party may adversely affect understanding by people with schizophrenia, at least when understanding is evaluated on the basis of a recognition test.

Situations involving a high degree of stimulation or complexity may pose a greater challenge to people with schizophrenia than to those without schizophrenia. The presence of an additional person and the disruption created by the facilitator's interventions may have been particularly confusing to people with schizophrenia. However, we offer the caveat that the facilitator in our study used only one set of graphic enhancements and one intervention protocol. Other investigators may want to explore variations on these themes.

Superior performance on recognition tasks, as opposed to recall tasks, was shown previously in a variety of contexts and with different populations (12,13,14). It has been shown that iterative feedback may improve understanding among elderly persons (16) and persons with schizophrenia (18,19). An important new finding of our study was that the healthy control group and the group with depression also benefited from this strategy. However, the exclusion of ten subjects who showed evidence of significant cognitive impairment—that is, an MMSE score below 24—limits the generalizability of this finding to individuals without such impairment.

One general limitation of this study was the use of a hypothetical clinical trial. Although this design allowed us to control the experimental manipulations and to identify specific effects of the various enhancements to the consent process, the participants knew that they would not really be taking a drug called petrinone and thus may have had diminished emotional involvement in the consent process. Another limitation was that we measured only one aspect of competence to consent—understanding. Other competence-related abilities, such as the capacity to express a choice, to appreciate how consent disclosure information applies to one's own clinical condition, or to rationally manipulate consent-related information, might have been affected differently by some of the experimental manipulations we explored (24). Finally, we did not explore the stability of the participants' understanding of disclosed information over time.

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that two recent strategies for improving the comprehension of research consent disclosures—graphically enhanced consent forms and mediation of the consent process by a third-party facilitator—may not be effective. However, the understanding of consent disclosures may be improved, at least in the short term, by providing iterative feedback to potential research participants who appear to have some initial difficulty with comprehension. Most participants could obtain a perfect score on the recognition measure with only two iterations of feedback.

Although more extensive educational efforts may be required for people who are more severely impaired (19), these procedures seem to be generally effective in promoting understanding of consent disclosures and may constitute the best strategy currently available for ensuring that the maximum number of potentially eligible individuals can safely and competently consent to participate in research (25).

Acknowledgment

This study was partly funded by grant R03-MH-56346-01 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors are affiliated with the department of mental health law and policy at the Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute of the University of South Florida, 13301 Bruce B. Downs Boulevard, Tampa, Florida 33612 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 227 participants in a study on understanding of research consent disclosures

|

Table 2. Mean±SD recall and recognition scores of 227 participants in a study on understanding of consent disclosures, along with first and best recognition scores of 111 participants who received feedback on recognition performance

1. Research Involving Persons With Mental Disorders That May Affect Decisionmaking Capacity. Washington, DC, National Bioethics Advisory Commission, Dec 1998. Available at http://bioethics.gov/capacity/ toc.htmGoogle Scholar

2. Delano SJ, Zucker JL: Protecting mental health research subjects without prohibiting progress. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:601-603, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

3. DeRenzo EG: The ethics of involving psychiatrically impaired persons in research. IRB: A Review of Human Subjects Research 16(6):7-9, 1994Google Scholar

4. Benson PR, Roth LH, Appelbaum PS, et al: Information disclosure, subject understanding, and informed consent in psychiatric research. Law and Human Behavior 12:455-475, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Reiser SJ, Knudson P: Protecting research subjects after consent: the case for the "research intermediary." IRB: A Review of Human Subjects Research 15(2):10-11, 1993Google Scholar

6. Baker MT, Taub HA: Readability of informed consent forms for research in a Veterans Administration Medical Center. JAMA 250:2646-2648, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Taub HA, Baker MT, Sturr JF: Informed consent for research: effects of readability, patient age, and education. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 34:601-606, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Young DR, Hooker DT, Freeberg FE: Informed consent documents: increasing comprehension by reducing reading level. IRB: A Review of Human Subjects Research 12(3):1-5, 1990Google Scholar

9. Ogloff JRP, Otto RK: Are research participants truly informed? Readability of informed consent forms used in research. Ethics and Behavior 1:239-252, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Waggoner WC, Mayo DM: Who understands? A survey of 25 words or phrases commonly used in proposed clinical research consent forms. IRB: A Review of Human Subjects Research 17(1):6-9, 1995Google Scholar

11. Peterson BT, Clancy SJ, Champion K, et al: Improving readability of consent forms: what the computers may not tell you. IRB: A Review of Human Subjects Research 14 (6):6-8, 1992Google Scholar

12. Taub HA, Baker MT: A reevaluation of informed consent in the elderly: a method for improving comprehension through direct testing. Clinical Research 32:17-21, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

13. Grisso T, Appelbaum PS: The MacArthur treatment competence study: III. abilities of patients to consent to psychiatric and medical treatments. Law and Human Behavior 19:149-174, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Appelbaum BC, Appelbaum PS, Grisso T: Competence to consent to voluntary psychiatric hospitalization: a test of the standard proposed by APA. Psychiatric Services 49:1193-1196, 1998Link, Google Scholar

15. Roth LH, Appelbaum PS: Obtaining informed consent for research with psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 6:551-565, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Taub HA, Kline GE, Baker MT: The elderly and informed consent: effects of vocabulary level and corrective feedback. Experimental Aging Research 7:137-146, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Taub HA, Baker MT: The effect of repeated testing upon comprehension of informed consent materials by elderly volunteers. Experimental Aging Research 9:135-138, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Wirshing DA, Wirshing WC, Marder SR, et al: Informed consent: assessment of comprehension. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1508-1511, 1998Link, Google Scholar

19. Carpenter WT, Gold JM, Lahti AC, et al: Decisional capacity for informed consent in schizophrenia research. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:533-538, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Frank E, et al: Competence in depressed patients for consent to research. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1380-1384, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

21. Woerner MG, Mannuzza S, Kane JM: Anchoring the BPRS: an aid to improved reliability. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 24:112-118, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

22. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 12:189-198, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Poythress NG, Cascardi M, Ritterband L: Capacity to consent to voluntary hospitalization: searching for a satisfactory Zinermon screen. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 24:439-452, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

24. Meisel A, Roth LH: What we do and do not know about informed consent. JAMA 246:2473-2477, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Appelbaum PS: Missing the boat: competence and consent in psychiatric research. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1486-1488, 1998Link, Google Scholar