Self-Reported Needs for Care Among Persons Who Have Suicidal Ideation or Who Have Attempted Suicide

Abstract

This study examined the self-reported needs of suicidal users of mental health services and the extent to which needs were met. Data on 10,641 adults were available from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. In the year before the survey, 245 persons with suicidal ideation used services, 37 of whom had attempted suicide. Suicidal persons reported a range of needs, especially for counseling, medication, and information. More than half of those with suicidal ideation and those who had attempted suicide who reported any needs felt that their needs had not been fully met. Suicidal persons were significantly more likely to perceive that they had needs.

Many individuals who commit suicide use services close to their time of death, but little is known about whether the care provided to suicidal patients meets their needs. This lack of knowledge is not surprising, given the difficulties inherent in defining the needs of suicidal persons (1). Ratings of the level of suicidality derived from instruments may provide some objective indication of needs, but persons with the same rating may have different perceptions of their needs for care.

The assessment of subjective or perceived need (2) allows inferences to be made about needs, demands for services, and the adequacy of service responses. The only study we identified that addressed this issue found that suicidal patients were more likely than others to feel a need for mental health services, but less likely to report that their needs had been met (3).

This study examined the self-reported needs of suicidal and nonsuicidal service users and their reports about the extent to which their needs had been met.

Methods

The study used data from the Australian National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (4). Trained nonclinical interviewers collected self-report data from a clustered probability sample of 10,641 participants who were 18 years of age or older. The survey included items related to suicidality, service use, and perceived needs and was conducted between May and August 1997. The response rate was 78 percent.

To assess suicidality the survey incorporated a modified version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (5), which asked participants about their suicidal ideation and suicide attempts during the previous 12 months. Each variable was coded as any versus none. Only participants who answered affirmatively at least one of two probe questions about subclinical depression were asked about suicidal ideation. The two probe questions were: "In the past 12 months, have you had two weeks or longer where nearly every day you felt sad, empty, or depressed for most of the day?" "In the past 12 months, have you had two weeks or longer where you lost interest in most things, such as work, hobbies, and other things you usually enjoyed?"

Participants who did not answer either probe question affirmatively were assumed not to have considered suicide, because those who had not experienced periods of sadness, emptiness, or subclinical depression would have been unlikely to have done so. Likewise, only those with suicidal ideation were asked about attempts, because attempts would normally be preceded by contemplation.

The survey provided data on each individual's use of six services for mental health problems during the preceding 12 months. The study examined whether or not respondents had used inpatient services; services from a general practitioner, a psychiatrist, a psychologist, or other mental health professional; or services from a non-mental-health professional.

Participants who used services were asked whether they felt they had needs in any of five areas. Responses were classified as any versus no need. The first area was information, such as information about mental illness, its treatments, and available services. The second area was medications. The third was counseling, which covered three service types: psychotherapy, or "causes that stem from your past"; cognitive-behavioral therapy, or "learning how to change your thoughts, behaviors, and emotions"; and counseling, or "help to talk through your problems." The fourth needs area was skills training, or "help to sort out housing or money problems," "help to improve your ability to work, or to use your time in other ways," or "help to improve your ability to look after yourself or your home." The fifth area was social interventions, or "help to meet people for support and company."

Participants were asked whether they felt that each intervention met their perceived needs. Perceived needs were considered fully met when individuals received as much of the given type of help as they felt they needed. Needs were not fully met when participants did not receive the type of help they needed or received less than they felt they needed.

Odds ratios were calculated to compare participants who had suicidal ideation or had attempted suicide with those who neither thought about suicide nor attempted it. The statistical technique of jackknife replicate weighting provided for estimation of all statistics taking into account the design error arising from the clustered probability sampling methodology (6). Analyses were carried out with SUDAAN, version 7.5.3.

Results

In the 12 months preceding the survey, 245 persons with suicidal ideation used services, including 37 persons who attempted suicide.

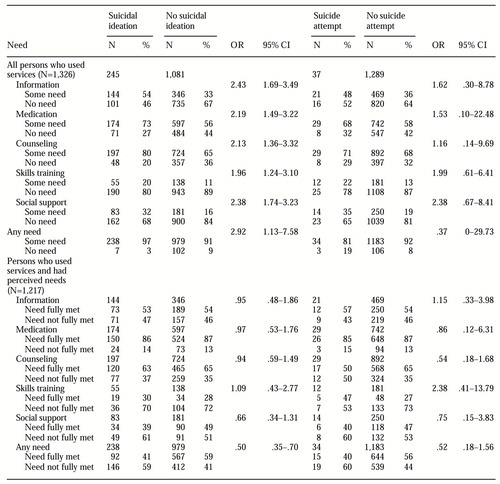

Table 1 presents information about all persons who used services for mental health problems in the 12 months before the survey in terms of whether or not they reported suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt. The table also provides data on perceived needs and the extent to which they were met. The needs most commonly reported by suicidal persons were for counseling, medication, and information.

Persons with suicidal ideation were significantly more likely than nonsuicidal persons to perceive that they had each of the five types of need. Among those with suicidal ideation, 97 percent expressed at least one type of need, compared with 91 percent of those who did not have suicidal ideation. Persons who attempted suicide were more likely than those who did not to report each type of need; however, the differences were not significant. The small size of the group of persons who attempted suicide reduced the power of the statistical analysis to test for differences; the analyses were more powerful with the larger group of those who reported suicidal ideation.

Surprisingly, those who attempted suicide were less likely than those who did not attempt suicide to express any need. Additional analyses, not reported in detail here, examined the relative number of need categories reported. The seeming anomaly was explained by the fact that those who attempted suicide were more likely to have multiple needs than those who did not.

Among suicidal persons the need most commonly reported to have been met was the need for medication, followed by the need for counseling and the need for information. No significant difference was found between those with and those without suicidal ideation in the extent to which they felt the different types of perceived needs had been met. However, only 41 percent of those with suicidal ideation reported that all of their needs had been fully met, compared with 59 percent of those did not have suicidal ideation. No significant difference was found between those who attempted suicide and those who did not in the extent to which they felt their needs had been met, in terms of either the five types of needs or any need.

Discussion and conclusions

Suicidal individuals who gain access to services have a range of needs. The study found that persons who had suicidal ideation were more likely to experience needs than those who did not have suicidal ideation. A smaller proportion of those who reported suicide attempts than of those who did not reported a large number of needs. Among service users who had attempted suicide, a small but clinically significant minority (19 percent) reported no perceived needs.

We found that suicidal persons most commonly perceived a need for counseling, medication, and information. Only a minority of the suicidal persons reported needs for skills training or social support; however, significantly more suicidal than nonsuicidal persons reported needs in these areas. Both skills training and social support have been demonstrated to have a protective effect against self-harm (7,8).

More than half of the respondents who had suicidal ideation and more than half of those who had attempted suicide who reported at least one need felt that their needs had not been fully met. Those who reported suicidal ideation were more likely to feel that their needs had not been fully met than those who reported no suicidal ideation; for those who reported attempts, this difference was similar in size to the difference for those with suicidal ideation, but it was not statistically significant. Among the suicidal individuals, the need for counseling was most commonly reported to have been fully met.

Two recent large-scale audits suggest that some suicides might be prevented if services were more responsive to the needs of suicidal individuals (9,10). For a minority of suicidal individuals who do not express any perceived needs, providing more responsive services will be a particular challenge. For the majority of suicidal people, clinicians should be more responsive to perceived needs. Both audits recognized that suicidal patients are among the most challenging to manage, often displaying characteristics that engender negative feelings among clinicians (9,10). Clinicians can be more responsive to clients' needs only when the agencies they work for support them by promoting relevant guidelines and providing supervision and debriefing opportunities.

Acknowledgments

The National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing was funded by the mental health branch of the Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, under the National Mental Health Strategy. The survey was conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Greg Carter, F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., was responsible for modifying the suicidality questions in the Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Ms. Pirkis is senior research fellow and Dr. Dunt is associate professor in the program evaluation unit at the Centre for Health Program Evaluation of the department of general practice and public health at the University of Melbourne, P.O. Box 477, West Heidelberg, Victoria, 3081, Australia (e-mail, [email protected]. edu.au). Ms. Pirkis is also affiliated with the Mental Health Research Institute in Parkville, Victoria, along with Dr. Burgess and Dr. Meadows.Dr. Burgess is also associate professor in the department of psychological medicine in the Faculty of Medicine at Monash University in Clayton, Victoria. Dr. Meadows is also senior lecturer in the department of psychiatry in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Melbourne in Parkville, Victoria.

|

Table 1. Self-reported need for services and self-reports of whether the need was met among 1,326 Australian adults who had used services for mental health problems, by whether they had experienced suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt

1. Meadows G, Fossey E, Harvey C, et al: The assessment of perceived need, in Unmet Need in Psychiatry: Problems, Resources, Responses. Edited by Henderson S, Andrews G. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 2000Google Scholar

2. Slade M: Needs assessment: involvement of staff and users will help to meet needs. British Journal of Psychiatry 165:287-292, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hintikka J, Viinamaeki H, Koivumaa-Honkanen HT, et al: Risk factors for suicidal ideation in psychiatric patients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:235-240, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Mental Health and Wellbeing: Profile of Adults, Australia, 1997. Canberra, Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1998Google Scholar

5. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): Researcher's Manual. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1994Google Scholar

6. Wolter KM: Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York, Springer-Verlag, 1985Google Scholar

7. Heikkinen M, Aro H, Lonnqvist J: Life events and social support in suicide (review). Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 23:343-358, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

8. D'Zurilla TJ, Chang EC, Nottingham EJ, et al: Social problem-solving deficits and hopelessness, depression, and suicidal risk in college students and psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology 54:1091-1107, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Burgess P, Pirkis J, Morton J, et al: Lessons from a comprehensive clinical audit of users of psychiatric services who committed suicide. Psychiatric Services 51:1555-1560, 2000Link, Google Scholar

10. Appleby L, Shaw J, Amos T, et al: Suicide within 12 months of contact with mental health services: national clinical survey. British Medical Journal 318:1235-1239, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar