Patterns of Use of Ambulatory Mental Health Services in a Universal Care Setting

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: As health care expenditures grow, it is important to understand whether mental health services are being used appropriately. This study examined participants' reasons for seeking the services of a psychiatrist or psychologist to determine the extent to which factors other than an existing clinical disorder, such as culture, stress, or lack of social support, played a role. METHODS: A total of 1,257 randomly selected students who were enrolled at the University of Geneva in 1997 and who had unrestricted access to psychiatric services were asked how many times in the past 12 months they had consulted a psychiatrist or a psychologist. The respondents' mental health, perceived stress, self-esteem, sense of mastery, and social support were measured with validated instruments. RESULTS: A total of 131 respondents (10 percent) reported an encounter with a mental health provider in the past year. In adjusted analyses, female sex, Swiss citizenship, a higher level of stress, and a lower level of mental health were significantly associated with a greater number of visits to a mental health specialist, and self-esteem, sense of mastery, and social support were not. CONCLUSIONS: The respondents' use of mental health services was determined by a lower level of mental health, indicating appropriate use of services based on clinical need. However, service use was also determined by consumer-related variables such as perceived stress and sociocultural characteristics.

The question of whether mental health services are being used appropriately is under increasing scrutiny. In particular, it is unclear whether a person's motive for seeking the services of a mental health professional is mainly the existence of a clinical disorder or whether other factors, such as culture, lifestyle, a high level of stress, or lack of social support, are involved (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9). In many countries, access to a mental health specialist is filtered through a general practitioner. This type of system minimizes the extent to which researchers can determine consumer-driven demand for mental health services.

Fewer than 10 percent of individuals in Switzerland are enrolled in managed care plans in which their access to specialty care is filtered through a general practitioner. All Swiss residents are covered by mandatory health insurance, mostly of the indemnity type, with no limits on mental health care, so that an individual can initiate a consultation with a mental health specialist. Furthermore, the density of suppliers of mental health services in Switzerland is among the highest in the world—for every 10,000 residents in Geneva in 1997, there were 31 physicians in private practice and about five psychiatrists. Mental health care can also be provided by a clinical psychologist, under the supervision of a psychiatrist. Most psychiatrists work in fee-for-service solo practice.

In such a system, where access to mental health services is virtually unrestricted, it is easier to determine whether the use of mental health services is driven more by consumer demand or more by professionally defined need. In this study we surveyed a sample of educated young adults in Geneva to determine whether their mental health status, perceived stress, self-esteem, sense of mastery, and social support were related to recent use of mental health services.

Methods

Sample

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of 2,000 randomly selected students who were enrolled at the University of Geneva in October 1997. A questionnaire was mailed to the students in November of that year, and up to two follow-up reminders were sent to nonrespondents over the next three months. Of the 1,954 students remaining after the deletion of incorrect or foreign addresses (98 percent), 1,257 (64 percent) responded to the questionnaire.

Variables and instruments

The dependent variable in the study was the students' use of ambulatory mental health services in the previous 12 months. Respondents were asked how many times during that period they had visited a psychiatrist or a psychologist and how many times they had visited other health care providers, such as a family doctor or a medical specialist. Respondents who reported at least one visit to a psychiatrist or a psychologist were classified as users. We did not ascertain whether visits to health professionals other than psychiatrists were motivated by a mental health problem.

We measured the respondents' mental health status with the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12), version 2 (10). Earlier versions of this instrument have been shown to accurately identify individuals who have a psychiatric disorder (11). Because algorithms to compute the physical health and mental health scores for version 2 were not available at the time of analysis, we performed a factor analysis of the 12 items, followed by varimax rotation. This analysis yielded a two-factor solution that can be used to represent physical and mental health constructs.

We used the resulting loadings to compute two orthogonal summary scores of mental and physical health, each being a distinct linear combination of the 12 items. Consistent with predictions, the general health item loaded moderately on both dimensions, and the other items loaded predominantly on the dimension they were designed to measure. Summary scores of physical and mental health were standardized to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10.

Perceived stress was measured with the Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument (BEPI) (12,13), a five-item scale that measures the balance between perceived daily life demands and capability to cope with these demands (for example, "In the past month, have you ever felt as if there are more demands in your life, emotionally and physically, than you can handle comfortably?"). Responses were scored on a scale of 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating worse functioning. The BEPI was internally consistent (Cronbach's alpha=.84), and a factor analysis confirmed that its items represented a single dimension.

Internal resources—sense of mastery and self-esteem—were measured with an eight-item instrument adapted from the work of Pearlin (14). The score for each subscale was computed by averaging the values of the corresponding items. Both subscales had good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha=.81 for self-esteem and .72 for mastery), and the bidimensional structure of the instrument was confirmed by factor analysis.

We used a six-item instrument adapted from the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (15) to measure confidant and affective social support. The score for each subscale was computed by summing relevant items. Internal consistency was satisfactory for both subscales (Cronbach's alpha=.70 for affective support and .79 for confidant support), and factor analysis confirmed the underlying constructs.

We used the official French translation of the SF-12. For the other scales, we produced French translations in a standardized procedure: three independent translations, selection of a consensus translation by an expert panel, and pretests. A description of the items and detailed validation of the instruments are available from the authors.

Data analysis

The mental and physical health and other psychological and sociodemographic characteristics of users of ambulatory mental health services were compared with those of nonusers. To examine the linearity of relationships, psychometric scores were split into five discrete levels: the lowest decile, the remainder of the first quartile (percentiles 11 to 25), and the second, third, and fourth quartiles. For stress, we isolated the highest decile, because high scores denote worse levels of functioning. Cross-tabulations and chi square tests were used for univariate analyses, and logistic regression was used to build multivariate models of mental health service use. A backward stepwise approach was used to identify the variables included in the final model. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with a significance level of .05.

Results

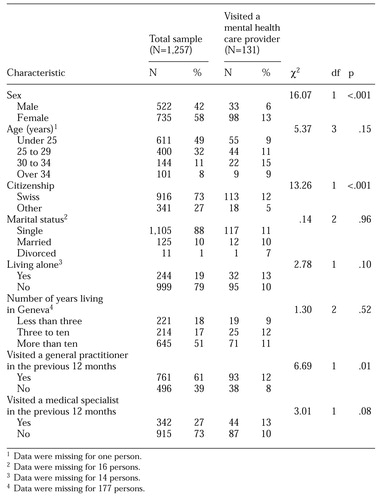

The sociodemographic characteristics of the 1,257 respondents are shown in Table 1. Their mean±SD age was 26±5.6 years, and slightly more than half were women. The majority were Swiss citizens who had been living in Geneva for ten years or more. Most were single and lived with another person or persons. Their monthly income was less than 2,000 Swiss francs (approximately $1,200 U.S.). The mean number of years they had spent at the university was 4±2.2 (range, 1 to 20 years).

Use of mental health services

A total of 131 respondents (10 percent) reported one or more visits to a mental health provider within the past 12 months: 79 respondents (6 percent) had seen a psychiatrist, 56 (5 percent) had seen a psychologist, and 4 (.3 percent) had visited both. These 131 users had a combined total of 2,707 visits (mean±SD=21±24; lower quartile=3, median quartile=10, upper quartile=33; range, 1 to 99), which pushed the general annual mean, including nonusers, to 2.2±10. Users were more likely to be women and to be Swiss citizens. They also reported more frequent visits to their general practitioner during the past year.

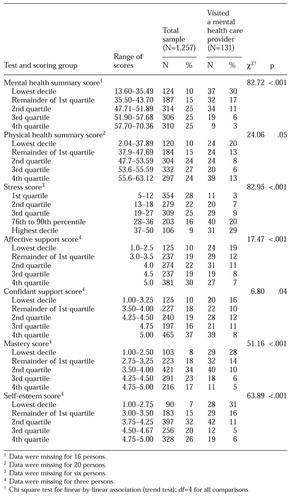

As Table 2 shows, lower mental health scores, higher perceived stress scores, and lower scores on measures of affective social support, sense of mastery, and self-esteem were significantly related to respondents' use of mental health services. The unadjusted relationships with physical health and confidant social support were weaker and of borderline statistical significance.

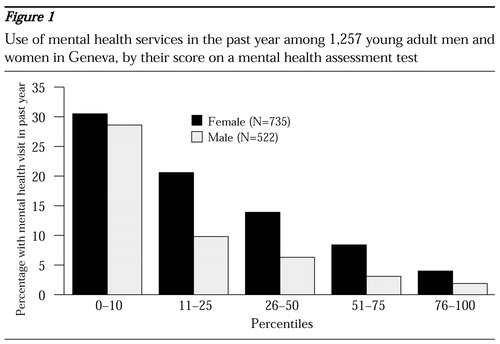

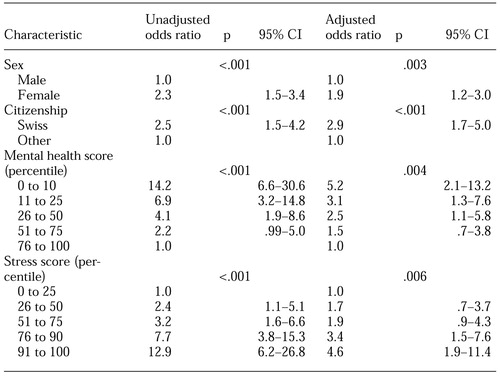

As Table 3 shows, the multivariate analysis indicated that women, Swiss nationals, and individuals with lower mental health scores and higher stress scores were significantly more likely to report a mental health visit in the past year. No statistically significant relationships were found between these determinants. The difference between men and women disappeared at the lowest level of mental health (Figure 1), and the difference between Swiss citizens and noncitizens increased as mental health scores worsened (Figure 2). However, no statistically significant interactions were found between these determinants.

Because family doctors often refer patients to mental health specialists, we built a second model that included visits to a general practitioner within the past year as a predictor of mental health service use. We found a significant interaction term between a past-year visit to a general practitioner and gender (p=.02). Women who had visited a general practitioner during the past year were three times more likely to report a mental health visit than women who had not, even after the analysis adjusted for the women's mental health and perceived stress. However, no differences in mental health visits were found between men who did and did not report a general practitioner visit.

Discussion

The use of mental health services in our sample of young residents of Geneva was high, a finding that confirms those of previous reports (16). Despite the easy access to mental health care specialists in the setting we studied, our results suggest that use of mental health services was in large part medically appropriate, that is, it was driven by a mental health problem. First, the respondents who reported frequent use of mental health services also had health survey scores that indicated significantly poorer mental health. Similar results were obtained by others (17). Second, the mean of 21 consultations per user suggests that in most cases a course of therapy had been initiated by the mental health specialist. In addition, the strength of the relationship between mental health status and visits to mental health professionals may have been underestimated in our study, because the time frame of health service use—the previous 12 months—was different from that of the health status measurement—the previous month—as well as because of measurement error due to the self-report nature of the study.

The role of stress

Perceived stress remained strongly associated with the use of mental health services even after adjustment for mental health status. Because perceived stress is not a psychiatric diagnosis, this finding points to an expanding social role for mental health specialists: psychiatrists are called upon not only to care for mental illness, but also to help individuals deal with the pressures of everyday living. For example, people who lack informal social support may seek professional support to cope with a stressful lifestyle. Whether or not this use of mental health services is appropriate is unclear; payers and users may differ in their perspectives on this issue. An alternative explanation for our findings is that the SF-12 did not adequately capture information about important aspects of mental health—for example, anxiety—that were better measured by the BEPI.

Other risk factors

The respondents' levels of sense of mastery, self-esteem, and social support were not independently associated with their use of mental health services after adjustment for mental health status and stress. Either these factors do not affect the use of mental health services at all, or they exert their influence by altering mental health status and levels of perceived stress, which in turn determine service use. It is important to clarify which of these hypotheses is true. The first implies that improvements in social support or self-esteem would not influence use of mental health services. The latter suggests the opposite, that acting upon the root causes of high levels of stress and poor mental health may help reduce the need for mental health services.

The remaining predictors of mental health service use in our study—sex and nationality—can be considered predisposing factors (18). The difference in the use of mental health services between men and women has been described in other studies (4,19). Some authors attribute this difference to a higher susceptibility among women to depression and other psychiatric disorders. However, our data indicate that women are more likely to consult with a psychiatrist, even after the analysis adjusted for mental health status. This finding suggests that women have greater access to mental health care than men, perhaps because they are more readily referred to psychiatrists by other doctors or because women attach less stigma to consulting a psychiatrist than do men.

Several possible explanations exist for the differences found between respondents who were Swiss citizens and those who were not. Foreign students may express a culturally determined pattern of symptoms of mental distress that is not readily recognized by Swiss health care providers. Although they are covered by mandatory health insurance, foreign students may have more difficulty using available resources, because they lack familiarity with the system, or they may be more reluctant to seek mental health care, again for cultural reasons (20). Finally, because psychiatric care relies so heavily on verbal skills, students who speak less than perfect French—the local language—may be less inclined to consult a mental health care specialist because of the verbal nature of psychiatric therapy itself.

Other factors that have generally been described as barriers to accessing mental health services (21,22,23,24,25) were not found to be significant among our respondents. The characteristics of our study sample precluded the examination of education level, which was uniformly high. It was also not possible to investigate income, which was above the poverty level but generally moderate, and health insurance coverage, which is universal.

Clinical implications

The results of our study raise several important points about consultations with mental health specialists. First, the strong relationship between mental health status and the use of mental health services suggests that individuals in the general population tend to contact mental health specialists appropriately and that such specialists should not fear an onslaught of frivolous consultations if barriers to access were lifted.

Second, our results suggest that perceived stress is an issue that must be reckoned with by the health care system. Whether problems with stress should be handled by general practitioners or by mental health specialists remains unclear. To be managed effectively, stress must be reliably identified during medical visits, which suggests that brief instruments such as the BEPI may have clinical applications.

Finally, the higher consultation rates found among women and Swiss nationals, after adjustment for mental health and stress, indicate that social and cultural determinants of the use of mental health services need to be better understood, especially in systems in which primary care physicians regulate patients' access to specialized services.

Limitations

The main limitation of our study was its cross-sectional nature, which precluded evaluation of temporal precedence and causality of the observed relationships. Another limitation, as noted above, was the exclusive reliance on self-reported rating scales and past use of medical services, which raises the issue of measurement error. Other research on the prescription of psychotropic medication by specialists and general practitioners (26,27) suggests that the use of self-reports of visits to a psychiatrist or a psychologist may result in underestimates of actual use. Finally, the generalizability of our findings is limited by the inherent characteristics of the study population—educated young adults—and the Swiss health system.

Conclusions

In this study, the use of mental health services was found to be strongly related not only to mental health status but also to self-perceived stress, which was defined as an imbalance between the demands of everyday activities and the capacity to cope with these demands. Given the costs generated by stress-related mental health service use, the development of strategies to reduce or manage stress in a cost-effective manner should be given a high priority by all health care professionals.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by a grant from the office of the rector of the University of Geneva.

Dr. Bovier is with the department of community medicine, Dr. Eytan is with the department of psychiatry, and Dr. Perneger is with the quality of care unit at the University of Geneva Hospitals, 24 rue Micheli-du-Crest, 1211 Geneva 14, Switzerland (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Chamot is with the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine at the University of Geneva.

Figure 1. Use of mental health services in the past year among 1,257 young adult men and women in Geneva, by their score on a mental health assessment test

Figure 2. Use of mental health services in the past year among young adults in Geneva who were or were not Swiss citizens, by their score on a mental health assessment test

|

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of young adults in Geneva who participated in a survey about their use of mental health services in the previous year

|

Table 2. Scores on assessment tests of young adults in Geneva, by whether they visited a mental health professional in the previous year

|

Table 3. Characteristics associated with making one or more mental health visits in the previous year among 131 young adults in Geneva

1. Manning WG Jr, Wells KB: The effects of psychological distress and psychological well-being on use of medical services. Medical Care 30:541-553, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Sherbourne CD: The role of social support and life stress events in use of mental health services. Social Science and Medicine 27:1393-1400, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Sherbourne CD, Meredith LS, Rogers W, et al: Social support and stressful life events: age differences in their effects on health-related quality of life among the chronically ill. Quality of Life Research 1:235-246, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Wells KB, Manning WG, Duan N, et al: Sociodemographic factors and the use of outpatient mental health services. Medical Care 24:75-85, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Williams SJ, Diehr P, Drucker WL, et al: Mental health services: utilization by low-income enrollees in a prepaid group practice plan and in an independent practice plan. Medical Care 17:139-151, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Diehr P, Williams SJ, Martin DP, et al: Ambulatory mental health services utilization in three provider plans. Medical Care 22:1-13, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Padgett DK, Patrick C, Burns BJ, et al: Ethnicity and the use of outpatient mental health services in a national insured population. American Journal of Public Health 84:222-226, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Briones DF, Heller PL, Chalfant HP, et al: Socioeconomic status, ethnicity, psychological distress, and readiness to utilize a mental health facility. American Journal of Psychiatry 147:1333-1340, 1990Link, Google Scholar

9. Simon GE, VonKorff M, Durham ML: Predictors of outpatient mental health utilization by primary care patients in a health maintenance organization. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:908-913, 1994Link, Google Scholar

10. Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD: A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care 34:220-233, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Berwick DM, Murphy JM, Goldman PA, et al: Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Medical Care 29:169-176, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Frank SH, Zyzanski SJ: Stress in the clinical setting: the Brief Encounter Psychosocial Instrument. Journal of Family Practice 26:533-539, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

13. Frank SH, Zyzanski SJ, Alemagno S: Upper respiratory infection: stress, support, and the medical encounter. Family Medicine 24:518-523, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

14. Pearlin LI, Schooler C: The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 19:2-21, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Broadhead WE, Gehlbach SH, de Gruy FV, et al: The Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire: measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Medical Care 27:709-723, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Perneger TV, Allaz AF, Etter JF, et al: Mental health and choice between managed care and indemnity health insurance. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1020-1025, 1995Link, Google Scholar

17. Bijl RV, Ravelli A: Psychiatric morbidity, service use, and need for care in the general population: results of the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. American Journal of Public Health 90:602-607, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Aday LA, Andersen RM: Equity of access to medical care: a conceptual and empirical overview. Medical Care 19:4-27, 1981Crossref, Google Scholar

19. Rhodes A, Goering P: Gender differences in the use of outpatient mental health services. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:338-346, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al: Gaps in service utilization by Mexican Americans with mental health problems. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:928-934, 1999Link, Google Scholar

21. Taube CA, Kessler LG, Burns BJ: Estimating the probability and level of ambulatory mental health services use. Health Services Research 21:321-340, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

22. Taube CA, Rupp A: The effect of Medicaid on access to ambulatory mental health care for the poor and near-poor under 65. Medical Care 24:677-686, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Cohen P, Hesselbart CS: Demographic factors in the use of children's mental health services. American Journal of Public Health 83:49-52, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Alegria M, Bijl RV, Lin E, et al: Income differences in persons seeking outpatient treatment for mental disorders: a comparison of the United States with Ontario and the Netherlands. Archives of General Psychiatry 57:383-391, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Sharfstein SS, Taube CA: Reductions in insurance for mental disorders: adverse selection, moral hazard, and consumer demand. American Journal of Psychiatry 139:1425-1430, 1982Link, Google Scholar

26. Wells KB, Manning WG Jr, Benjamin B: Comparison of use of outpatient mental health services in an HMO and fee-for-service plans: sensitivity to definition of a visit. Medical Care 25:894-903, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Olfson M, Pincus HA: Measuring outpatient mental health care in the United States. Health Affairs 13(5):172-180, 1994Google Scholar