Effects of Disability Compensation on Participation in and Outcomes of Vocational Rehabilitation

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors sought to determine the relationship between receipt of disability compensation and participants' success in a vocational rehabilitation program. METHODS: Administrative data for 22,515 individuals who participated in the Veterans Health Administration compensated work therapy program between 1993 and 1998 were analyzed. Six dependent variables were compared between participants who were receiving disability compensation and those who were not: duration of participation in compensated work therapy, number of hours worked per week, mean hourly earnings, total income from compensated work therapy, dropout rate, and competitive employment status at discharge. Regression equations were determined for each dependent variable to assess associations with the degree of disability, the amount of disability compensation, and the type of compensation program. RESULTS: Participants who were receiving disability benefits worked fewer hours in compensated work therapy each week, earned less income, had a higher dropout rate, and were less likely to be competitively employed at discharge. The amount of compensation and the type of program were modestly but significantly associated with participation in compensated work therapy and with outcome. CONCLUSIONS: Unintended effects of disability compensation programs discourage full participation in vocational rehabilitation and result in poorer rehabilitation outcomes.

Despite the motivation of disabled adults to return to work (1) and the continuing efforts to identify effective models of rehabilitation (2,3), many vocational rehabilitation efforts have been described as a failure (3). The reasons for the disappointing results are unclear. One possible factor is the impact of public support programs, such as indemnity programs, insurance programs, and disability compensation programs. Although these programs have important differences, they share the central feature of providing direct financial support to disabled adults. For the purposes of this article, we will refer to these programs as disability compensation programs.

Adults who have disabilities commonly use both vocational rehabilitation and disability compensation programs. Although these two types of services have similar goals, at certain points in recovery they may produce conflicting incentives. Disability compensation programs pay financial benefits during the period of disability, whereas vocational rehabilitation programs help clients regain financial independence through competitive employment.

Vocational rehabilitation and disability compensation programs are often seen as complementary, but concerns about the potential long-term negative impact of disability compensation on return to work have been raised. Leonard (4) found that payment of Social Security disability benefits fostered withdrawal from the workforce beyond the effects of illness. Similarly, a significant but small association was found between nonparticipation in the workforce and receipt of a high level of compensation from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) for service-connected disabilities (5). In the only study in which both vocational rehabilitation and disability income were examined directly, Nichols and associates (6) found evidence that resistance to seeking competitive employment was greater among clients who were receiving Social Security benefits.

Disability benefits may be related to participation in vocational rehabilitation in at least three ways. First, receipt of benefits and participation in vocational rehabilitation may covary with a client's degree of functional impairment. Second, benefit payments may reduce the financial incentive to participate in vocational rehabilitation and to seek competitive employment. Third, the risk of losing benefits may be a disincentive to earning income, thus reducing participation in paid vocational rehabilitation activities and reducing motivation for competitive employment. Although the first factor represents the predicted effect of participants' impairment or illness, the remaining two factors represent unintended barriers to rehabilitation that result from compensation programs themselves. Previous studies have not distinguished these three factors or tried to determine their relative effects.

The Veterans Healthcare Administration (VHA) provides compensated work therapy, a form of vocational rehabilitation services, to more than 18,000 veterans each year. Participants in this program must have a diagnosed condition that affects their ability to work. More than 28 percent of participants in compensated work therapy receive some form of disability compensation (7).

The two types of disability compensation programs most commonly used by veterans are the VA compensation program and the Social Security disability compensation programs, including Social Security Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income. The VA and Social Security programs differ in several important ways, including the amount of compensation available and restrictions on competitive earnings. Social Security disability benefits have clear restrictions, and benefits are reduced or eliminated if the client returns to productive employment. Disability compensation provided by the VA does not have the same restrictions, and any restrictions are not enforced as strictly, which allows most participants to return to gainful employment without penalty (8). For a fuller description of VA and Social Security programs, several references are available (8,9,10,11).

In this study we sought to determine the impact of disability compensation on participation in vocational rehabilitation. In a sample of vocational rehabilitation participants, many of whom received Social Security disability benefits, VA disability benefits, or both, we tested three hypotheses. The first hypothesis was that participants who were receiving disability compensation would have a lower rate of participation in vocational rehabilitation and poorer outcomes than those who were not.

The second hypothesis was that for participants who were receiving disability benefits, the amount of compensation would be significantly related to participation in vocational rehabilitation and to outcomes after the level of disability as well as demographic and background variables had been controlled for, with higher disability incomes being associated with lower participation and poorer outcomes.

Our third hypothesis was that participants who were receiving disability benefits with greater disincentives for earned income—Social Security benefits—would have a lower rate of participation in vocational rehabilitation and poorer outcomes after the effects of their disabling condition, demographic and background variables, and the amount of disability compensation income had been controlled for. For the purposes of this article, "lower rate of participation" is defined as a shorter length of stay in the program, fewer hours of participation in compensated work therapy per week, lower earnings, and a higher dropout rate.

Methods

Administrative data for 22,515 individuals who participated in the compensated work therapy program of the VHA between 1993 and 1998 were analyzed. Compensated work therapy is the primary vocational rehabilitation program in the VHA. The program currently operates at more than 100 sites in 42 states and the District of Columbia. The format of the program is fairly consistent across sites, using a mixed model of vocational rehabilitation that includes transitional employment, sheltered workshops, and job placement (12).

The stated goal of compensated work therapy is to help maximize participants' levels of functioning while preparing some for a successful return to competitive employment and providing longer-term work placements to others (13). The clients are predominantly middle-aged male veterans, most of whom have a substance use problem, a psychiatric problem, or both, and many also have medical problems. Most participants have a long history of vocational difficulties (13). The limited evaluation data on the program suggest that participation in compensated work therapy is associated with lower rates of drug and alcohol use and fewer episodes of homelessness and incarceration (14).

For this study we used the complete set of administrative data collected by the Northeast Program Evaluation Center, which has monitored all compensated work therapy programs since 1993. At each site, data are collected by vocational rehabilitation specialists, who are the primary professional staff, in a clinical interview at intake and at discharge and from medical and financial records of the compensated work therapy program. Independent variables include demographic characteristics, diagnosis, the amount of disability benefits, and the type of disability benefits received.

Six dependent variables were selected—five that describe the degree of participation in compensated work therapy and one that describes outcome. Length of stay in the program, mean number of hours of participation per week, mean hourly earnings, total earnings during participation, and whether the participant dropped out of the program were used to measure participation. Whether the participant was placed in competitive employment at discharge was our outcome measure.

Length of stay was defined as the number of days from the intake date to the discharge date. Although length of stay is a common measure of participation, it does not take into account the number of hours of participation a week, which can be thought of as a measure of the intensity of participation. Because income is potentially relevant to restrictions on disability compensation, the total amount of money earned in the program is included. Premature voluntary termination is a common problem in many clinical programs, including vocational rehabilitation programs, and is potentially related to disability compensation. Placement in competitive employment at discharge is probably the most common outcome sought by vocational rehabilitation programs.

Veterans 60 years of age and over and veterans who were receiving Social Security retirement benefits were excluded from the study to ensure that retired adults and those who were approaching retirement age, who may have different motivations or goals for vocational rehabilitation, were not included. A total of 310 veterans who reported receiving disability benefits from a source other than the VA or Social Security, representing 1 percent of the initial sample, were also excluded, because data were not available on regulations governing those benefits. In addition, 628 (3 percent) of the initial sample who received other types of public support, such as welfare payments, were also excluded, because of the potential confounding effect of these additional funds and their associated constraints on subsequent work participation.

The analyses were conducted in two stages. During the first stage, to test the first hypothesis, participants who were receiving disability benefits were compared with those who were not in terms of participation in compensated work therapy and outcomes. The aim of the second stage was to identify factors related to disability compensation status that may have accounted for differences between groups. Stepwise regression equations were determined for each of the dependent variables.

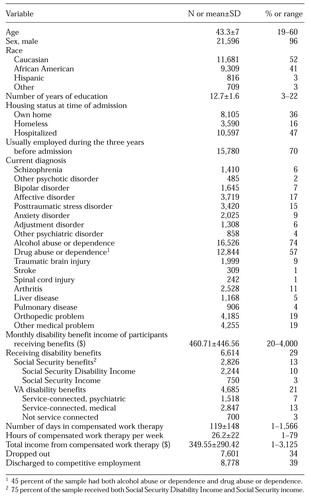

Each equation involved three steps. In step 1, demographic variables—age, sex, race, education, marital status, and whether the participant had children—were included as covariates. Also included were nine of the most common psychiatric and medical diagnoses or clusters of diagnoses, including alcohol abuse and drug abuse, as listed in Table 1, as well as a general residual category for both psychiatric and medical diagnoses. Two medical diagnostic groups—multiple sclerosis and dementia—were excluded, because they involved fewer than .1 percent of the participants. Variables such as employment status and housing status at the time of admission were not included, because they are closely related to compensation income and therefore are not independent covariates.

In step 2, the total amount of income from disability benefits was included as an independent variable to determine its impact on participation and outcome beyond step 1 variables. In step 3, the type of benefit program was included to determine the impact of the type of program—Social Security or VA disability compensation program.

Results

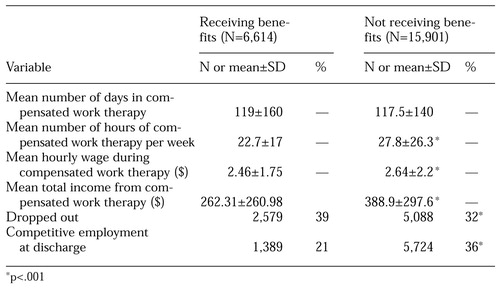

Demographic and other variables for the sample are summarized in Table 1. We found strong support for the first hypothesis. Participants who were receiving disability benefits were significantly different from those who were not receiving benefits on most of the participation and outcome variables, as can be seen in Table 2. Although the number of days in which veterans who were receiving benefits participated in compensated work therapy was not significantly different, the number of hours of participation per week was 18 percent lower (t=14.19, df=1, 22,513, p<.001). The hourly wage of participants who were receiving disability compensation was 7 percent lower than that of participants who were not (t=2.66, df=1, 22,513, p<.01), and their total income from participation in compensated work therapy was 33 percent lower (t=13.05, df=1, 22,513, p<.001). Participants who were receiving disability compensation had a significantly higher dropout rate (χ2=120.71, df=1, 22,515, p<.001) and a significantly lower rate of competitive employment at discharge (χ2=500.90, df=1, 22,515, p<.001).

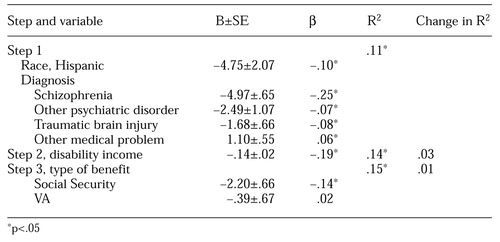

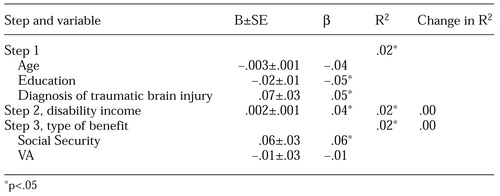

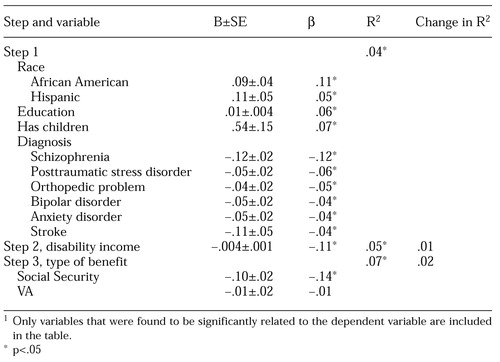

Bivariate and Pearson product-moment correlations between the independent and dependent variables were calculated. Length of stay in compensated work therapy was not significantly correlated with the amount or type of disability compensation. Regression equations were determined for the four dependent variables that were found to be related to disability compensation: mean number of hours of participation per week, total earnings during participation, dropout, and competitive employment at discharge. The three-step models accounted for 2 percent to 15 percent of the variance in the four dependent variables. The demographic and diagnostic variables accounted for at least 50 percent of the variance explained in all four equations, as shown in Tables 3, 4, and 5.

We also found support for the second hypothesis—that is, the amount of disability income had a negative association with participation in compensated work therapy and outcomes after demographic and diagnostic variables had been controlled for. The amount of disability income was modestly but significantly related to all four dependent variables, accounting for 1 percent to 3 percent of the variance in step 2. The amount of disability income had the largest association with total earnings from compensated work therapy.

Finally, our third hypothesis was also supported by the results. Participants who were receiving benefits from Social Security, a program that has higher disincentives for earned income, had lower rates of participation in compensated work therapy as well as poorer outcomes. When the type of benefit was included in step 3, Social Security benefits were significantly related to the number of hours worked, total earnings, dropout rate, and competitive employment at discharge. VA benefits were not negatively associated with any of the dependent variables. Entered in step 3, type of benefit accounted for up to 2 percent of the total variance; the greatest association with Social Security benefits was observed for competitive employment at discharge.

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study suggest that disability compensation programs, particularly those that carry disincentives to earn income, are associated with lower rates of participation in vocational rehabilitation. Overall, participants in compensated work therapy who were receiving disability income showed a pattern of substantially lower participation and poorer outcomes in terms of competitive employment. The greatest effect was observed for the amount of money earned in compensated work therapy and the rate of entry into competitive employment. The average earnings of participants who were receiving disability compensation were only 67 percent of those who were not receiving compensation. The group that was receiving compensation had 41 percent fewer placements into competitive employment. Length of stay in the work therapy program was the one dependent variable that was not related to disability status, which suggests that differences in other dependent variables were not attributable to differences in length of stay.

In addition to the disabling disorder and certain demographic variables, the amount of disability income and the type of program—Social Security or VA—were associated with a lower participation rate and poorer outcomes. The magnitude of the effect of amount of income and program type was small, accounting for no more than 4 percent of the variance in any of the dependent variables. However, in large programs small relationships can translate into large numbers of people employed or dollars spent. An alternative explanation is that the relationship between the type of program and outcome may reflect the severity of disability more than it reflects program regulations. The definition of disability and the means of evaluating disability are somewhat different between the Social Security and VA programs. The use of diagnoses to control for functional disability in the statistical model may have been inadequate to control for these differences.

To evaluate this possibility, we repeated the regression analyses with data from a subsample of 350 participants who had also completed the Short Form-12 (SF-12), a measure of medical and psychiatric quality of life (15). When the SF-12 scores were included in step 1 of the regression equations, a modest increase in the total variance that was accounted for by step 1 was noted for all four dependent variables, but no changes in the results for steps 2 and 3 were observed. This finding suggests that diagnoses were adequate to account for differences in functional impairment associated with participation in VA and Social Security programs.

These data suggest that the current compensation programs have created barriers to returning to work in addition to the physical and psychiatric barriers that are faced by adults with disabilities. Financial need is a key motivating factor for working and for participating in paid vocational rehabilitation. Disability benefits can reduce incentives or create conflicting incentives to participate in vocational rehabilitation or to return to work. Persons who receive compensation may want to work, but they also need to maintain their income for themselves and their families. The Social Security Administration has attempted to minimize these conflicting incentives by modifying the regulations of their programs (10). Despite these efforts, the current Social Security regulations apparently continue to create a greater disincentive for participating in rehabilitation than VA regulations.

This study was limited in several ways. As noted, the statistical model we used relies on diagnoses to represent functional disability. In addition, the range of variables that were available for analysis was limited. For example, the length of time a person receives disability compensation may play an important role in determining the impact of disability compensation, but information about length of disability was not available in this data set.

Future studies should clarify what recipients of disability compensation understand about Social Security work incentives and what additional changes would eliminate the disincentive. A cost-benefit analysis of the guidelines of the various programs would provide needed data about the financial cost of the current set of disincentives. Studies that use more precise measures of functional disability and that include other differences in the way recipients perceive the guidelines of the two programs will be helpful in clarifying the differences between the respective outcomes of the programs. Future studies may also address the potential exacerbating effect of income from vocational rehabilitation and disability compensation on substance use disorders, which are common in this and other patient populations.

Our study highlighted the unintended negative effects of disability compensation programs on vocational rehabilitation. These effects appear to be modest in magnitude but do result in fewer people returning to productive employment. In our efforts to eliminate the barriers faced by adults with disabilities in returning to work, we must include barriers that have been created unintentionally by our own efforts to help.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center of the Veterans Integrated Service Network 1. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Marcie Hiebert, Ph.D.

Dr. Drew is affiliated with Boston College. Dr. Drebing, Dr. Van Ormer, Ms. Losardo, Mr. Krebs, and Dr. Penk are with the Edith Nourse Rogers Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Bedford, Massachusetts. Dr. Rosenheck is with the Northeast Program Evaluation Center of the Connecticut Veterans Affairs Healthcare System in West Haven, Connecticut, and clinical professor of psychiatry and public health at Yale University School of Medicine. Send correspondence to Dr. Drebing at the Edith Nourse Rogers VA Medical Center, 200 Springs Road, 116B, Bedford, Massachusetts 01730 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic, diagnostic, disability benefit, and compensated work therapy variables among 22,515 veterans

|

Table 2. Differences in participation in and outcomes of compensated work therapy as a function of disability benefits in a sample of 22,515 veterans

|

Table 3. Summary of results of a hierarchical regression analysis for predicting total earnings during participation in compensated work therapy in a sample of 22,515 veterans

|

Table 4. Summary of results of a hierarchical regression analysis for predicting dropout among 22,515 veterans participating in compensated work therapy

|

Table 5. Summary of results of a hierarchical regression analysis for predicting competitive employment at discharge from competitive work therapy in a sample of 22,515 veterans1

1 Only variables that were found to be significantly related to the dependent variable are included in the table

1. Rogers ES, Walsh D, Masotta L, et al: Massachusetts Survey of Client Preferences for Community Support Services. Boston, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 1991Google Scholar

2. Drake R, Becker DR, Xie H, et al: Barriers in the brokered model of supported employment for persons with psychiatric disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation 5:141-149, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Noble JH, Honberg RS, Hall LL, et al: A Legacy of Failure: The Inability of the Federal-State Vocational Rehabilitation System to Serve People With Severe Mental Illnesses. Arlington, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 1997Google Scholar

4. Leonard JS: The Social Security Disability Program and Labor Force Participation. Washington, DC, National Bureau of Economic Research, 1979Google Scholar

5. Rosenheck R, Frisman L, Sindelar J: Disability compensation and work among veterans with psychiatric and nonpsychiatric impairments. Psychiatric Services 46:359-365, 1995Link, Google Scholar

6. Nichols M: Demonstration Study of Supported Employment Program for Persons With Severe Mental Illness: Benefits, Costs, and Outcomes. Indianapolis, Indiana University-Purdue University, psychology department, 1989Google Scholar

7. Drebing CE, Penk W, Rosenheck R: Readiness for Competitive Employment: Predicting "Success" of CWT Graduates. Presented at the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, August 4-8, 2000Google Scholar

8. Survey of Disabled Veterans. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, 1989Google Scholar

9. Red Book on Work Incentives. Washington, DC, Social Security Administration, 1995Google Scholar

10. Disability Evaluation Under Social Security. Washington, DC, Social Security Administration, 1998Google Scholar

11. Veterans' Benefits: Improvements Needed to Measure the Extent of Errors in VA Claims Processing. Washington, DC, US General Accounting Office, 1989Google Scholar

12. Seibyl CL, Rosenheck R, Corwel L, et al: Third Progress Report on the Compensated Work Therapy (CWT)/Veterans Industries (VI) Fiscal Year 1999. West Haven, Conn, VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 2000Google Scholar

13. Losardo ML: Veterans in Need of Services: The History and Development of the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial VA Hospital Compensated Work Therapy Program. Master's thesis. Boston, John W McCormack Institute of Public Affairs, University of Massachusetts, 1999Google Scholar

14. Kashner TM, Rosenheck R. Campinell AB, et al: Impact of Therapeutic Work on Homeless, Substance-Dependent Veterans: Final Report. Health Services Research and Development project IIR 92-043. Dallas, Tex, Veterans Health Administration, Aug 1998Google Scholar

15. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD: A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care 34:220-233, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar